Justin Sullivan

The following segment was excerpted from this fund letter.

Roku (NASDAQ:ROKU)

The Portfolio first bought Roku in Q3’20. It was a company we followed closely given our investment in The Trade Desk and its importance in connected television (CTV). Roku continued to impressively grow its CTV market share and it took some extra work to understand the underlying dynamics causing Roku’s success. I think there is some misunderstanding surrounding the connected television landscape. Since I haven’t written extensively on the topic in past letters, I thought it would be helpful to provide a little more background on the underlying dynamics of the space below.

Connected Television

The Internet has impacted media across different mediums. Newspapers, magazines, and music content have transitioned to digital with consumers able to access any content they want when they want it. Television has been slower to make the transition to internet distribution compared to other media but remains one of the preferred ways to consume content with the average American watching more than four hours of television a day.

The transition to the internet took long for several reasons. Households had to adopt high-speed broadband internet access which is required to stream TV. Older televisions could not connect to the internet and the average TV is replaced every seven to eight years. Therefore, consumers needed to either purchase a device/dongle to connect their TV or wait for the slower replacement cycle when they purchased a new smart TV.

Finally, the legacy cable networks that aggregated quality programming were slow to shift content online because it conflicted with the cable operators that distributed the content to households. Cable operators (Comcast, Charter) pay the cable networks (Fox, CNN, TNT, ESPN, MSNBC) for content to sell cable subscriptions to households. If the cable networks made their content available over the internet, cable companies could lose subscribers and therefore would hurt their revenue streams.

Advertisers were also hesitant to move to a new unproven medium, therefore offering little economic incentive to move content to streaming, at least initially.

Fast forward to today and CTV adoption has accelerated as most households have high speed internet, nearly all TVs are smart TVs, and premium content has transitioned to streaming with the last holdouts (live sports and news) finally moving to streaming.

Much of the focus on CTV has been on the streaming wars – the content battle between services like Netflix, Disney+, Hulu (owned by Disney), HBO Max, Paramount+, etc. While an increasing amount of capital is being invested in generating content to win subscribers, the real battle is over the TV operating system (TV OS). The TV OS will own the direct-to-customer relationship, data, and be best positioned to capture value from the TV value chain. One user interface for all content. The question is how will the TV operating system play out?

Netflix (NFLX) was the first mover to stream content over the internet by launching its service in 2007. At the time, the only way to stream TV was over a personal computer, game console, or DVD player. Netflix was working on a set-top box technology that could connect TVs to the internet.

However, management believed it would create a conflict of interest with other hardware providers that they wanted to support their streaming service. Netflix decided to focus on providing its content to all available players as opposed to owning a player that aggregates all the content. They spun out the technology in 2008, which then became Roku. Netflix would be available on Roku, letting Netflix offer its service on other connected devices while Roku could stream content from other providers on its device.

Following Netflix’s initial success, other streamers like Amazon Prime, Apple TV+, and Disney+ entered the market. The streamers (like the legacy cable network channels) became content aggregators for viewers. As a growing number of streaming services have become available over the last 15 years, it has provided the opportunity for devices to manage the different streaming apps.

Customers bought streaming players/devices to connect their TV to streaming. Roku, Amazon’s Fire Stick, and to a lesser extent, Google’s Chromecast, were initially successful at selling streaming players with simple and user-friendly interfaces that navigated an increasing number of streaming apps.

Television Operating System (TV OS)

While streaming devices initially enabled TVs to connect to the internet and stream apps, TVs now come with a built-in operating system. The TV has become a computer that runs third-party software. In computing ecosystems, there must be a central core around which the software and hardware are built upon called the operating system. It is like the conductor of an orchestra of software that runs computing devices such as PCs, smartphones, and increasingly, connected TVs. The OS sets and enforces standards, acting as the controller of ecosystems.

The natural economics of operating systems move towards concentration because of its two-sided network effect where third-party software application developers want to reach the most consumers, and consumers want the system with the most/best applications.

Connected television is following the path of Aggregation Theory which states that when it comes to digital goods distributed over the Internet (CTV content), whoever aggregates the direct relationship to consumers is positioned to generate the best returns in the value chain. Initially, aggregators must win customers by offering the best user experience by eliminating frictions and often initially subsidizing customer adoption. As the aggregator grows its customer base, digital supply wants access to those customers.

As more supply is available, it offers customers more value and creates a self-reinforcing two-sided network effect. Platforms that can best source, filter, and provide the best user experience can gain a foothold and build a dominant position in the value chain.

The best positioned companies are the ones that can control the TV and entire user experience by aggregating the aggregators. Search, discovery, and even filtering content is increasingly important to viewers. A major pain point is surfacing content for each user to watch without them having to endlessly scroll through numerous apps and channels. The best way to accomplish this is by licensing the OS to all the TV OEMs. As in following Google’s mobile playbook with Android mobile as opposed to Apple’s (AAPL) integrated iOS strategy.

TV OEMs must decide if they want to develop their own OS internally or license from a third-party provider. Early versions of TV OEMs that developed their own OS had poor user experiences, therefore viewers often purchased a streaming device. When it comes to purchasing TVs, hardware increasingly become “good enough” while the software/user experience is the problem to solve. Screen technology has become more commoditized with similar quality across OEM brands, therefore price has become very important when choosing between two similar quality TV brands.

If the TV OEM’s OS is not good enough, consumers have the ability to pick the TV based on screen size/quality and then switch to the TV OS of their choice by purchasing inexpensive dongles which provides the TV OS’ that have early leads with a big advantage. The question is if customers care about the TV OS they use? Can the largest TV OEMs like Samsung (OTCPK:SSNLF) and LG establish a large enough userbase to justify the costs to invest in their own OS?

As it stands today, there are six main TV OS players: Roku, Google TV, Amazon’s Fire TV, Samsung’s Tizen, LG’s webOS, and Vizio’s SmartCast. It is possible for all six to exist in end state and benefit from the long secular tailwind of CTV, but it is more likely that the TV OS will continue to consolidate and likely have an end state with maybe 2-3 major players. It is likely that the winning TV OS’ will have to license their software so that it available on any TV OEM hardware since consumers likely own multiple TV brands within one house and will prefer a single user experience.

It is possible for a TV OEM like Samsung to establish a large enough footprint to remain feasible, like how Apple did with the iPhone’s iOS. However, TV hardware is less differentiated among OEMs than the iPhone’s initial offering and therefore unlikely that a TV OS that is not licensed and available across numerous TV OEMs will be successful. Smaller to mid-sized OEMs that have attempted to build in-house OS’ have continued to lose share to OEMs that license their OS

Roku began licensing their OS in 2013 to smaller Chinese OEMs like TCL and Hisense who quickly gained share in the U.S. market with their low-price points and Roku’s user friendly interface. from a third party (Roku, Google TV, or Amazon Fire TV). Amazon (AMZN) has had less success licensing its Fire OS.

One potential reason is there are about four major retailers that sell the majority of TVs in the US (Walmart, Best Buy, Costco, and Target) and they view Amazon as their arch enemy. Therefore, TV OEMs have been hesitant to license Amazon’s Fire OS which may explain Amazon attempting to build its own branded Omni TV. Google (GOOG, GOOGL), which has had less success in its streaming devices but more success licensing its Android TV OS, recently rebranded to Google TV.

However, there are a lot of inefficiencies in a value chain that has multiple operating systems. It takes significant resources to develop the software, support the third-party content supplier’s software development, and sell the ad inventory to advertisers.

The longer seven-year average life cycle of the TV can work in Roku’s favor as it already established a strong lead. It is common for households to have multiple TVs from different OEM brands. Having a single OS throughout the house provides a better user experience so when you stop watching a show on the TV in the living room, you can pick up where you left off on your bedroom TV.

The Streaming Content

Some believe that the top streaming apps will scale and spend so much on content that they will push out smaller media companies with inferior content spending. If viewers consolidate in a small number of large streaming apps, this decreases the amount of value that Roku could capture as a distributor of content. I think over the long-term, streaming services will have a more difficult position than the TV operating system. The streamers must win consumers every single month by continually investing in new content. The TV operating systems like Roku only have to win the consumer once.

Netflix and Disney (DIS) are unlikely to be able to create their own connected devices or license operating systems and therefore will become increasingly reliant on the consolidating distributors of their content. Historically, Netflix benefitted from controlling content supply and having the direct-to-consumer (DTC) relationship. Going forward Netflix will increasingly lose the DTC relationship to whoever controls the television, and more specifically the OS on the television.

While the large streamers will likely play a big part of future TV viewing, no single streamer will be able to monopolize the industry. Sports and news alone will be offered over multiple streamers. If no single stream can monopolize TV, then there will need to be an aggregator to help bundle it. As consumers are maxed out on the amount they pay in subscription, free advertising-based content will become increasingly important to monetize content.

Advertising depends on maximizing reach and therefore the scale of the TV OS becomes that much more important to monetize content. Content supply, advertising dollars, and viewers will continue to migrate to the largest platforms that have the greatest reach and data.

There have also been questions surrounding Roku’s original content efforts as they build out The Roku Channel (TRC). There is a misconception that they are trying to compete directly with the likes of Netflix and Disney+ in the intense streaming wars. Roku’s motivation is to win control over the TV viewing experience. TRC provides the ability to incorporate all free content on one user interface. Paramount+, Disney+, and CBS All-access content can sit side by side as opposed to hidden behind apps that viewers must click through.

Investing in Roku Original content is to improve the content quality available on the app, thus drawing more viewers to TRC, providing third-party content suppliers’ incentive to plug into TRC without needing to invest in their own app or build their own audience. TRC now has over 200 licensed content partners and is growing at double the rate of the rest of Roku’s platform

Conclusion

It is inevitable that the future of TV will be CTV. Advertising dollars will move from linear TV to CTV. Total ad spend in the US is expected to be over $80 billion in 2022, with linear making up nearly $70 billion of it. It seems highly likely that TV operating systems will continue to consolidate with just a few remaining at end state.

All of CTV ad spend will have to go over the remaining TV OS’ and the OS’ will earn their take rate. Given their current reach, the most advantaged players to be those end-state winners are Google TV, Roku, and potentially Amazon Fire TV if they find a way to more successfully license their OS or sell enough Amazon-built TVs to establish a large enough userbase.

The TV OS’ with the largest user base also provides it with more bargaining power over content suppliers, providing it either with a higher take rate of ad inventory or subscription revenue share. They will have the widest reach, better user data, content discovery, and therefore, targeted ads. They will be able to earn higher CPMs on ad inventory and therefore show fewer commercials per hour, providing a better viewing experience for ad supported content.

In their most recent results, Roku reported softer advertising dollars as nearly half of advertisers paused ad campaigns in response to macro uncertainty. While advertising will come and go, the key is that Roku can continue to gather eyeballs and then the rest will work itself out in the long run. In my opinion, the market is underappreciating the power of Roku’s competitive advantage in the TV ecosystem and ability to scale far into the future.

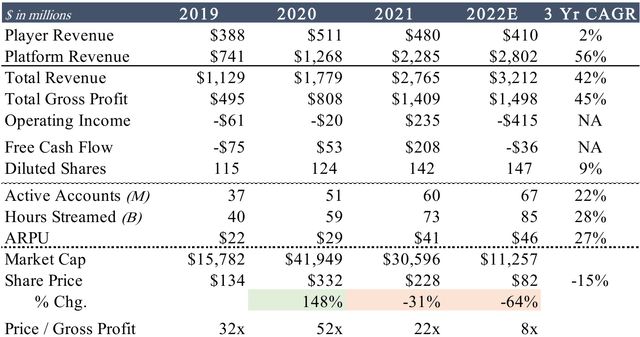

|

Source: Company filings, Factset, Saga Partners Note: 2022E values are Factset consensus expectations, market cap and share price are as of 6/30/22. |

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment