instamatics

Transcript

We have argued for a while that the Great Moderation – a period of steady growth and inflation – is over. Central bankers at the recent Jackson Hole economic forum started to explicitly acknowledge this.

But they are still solving for the politics of inflation and do not intend – for now – to manage the sharper trade-offs.

Federal Reserve not backing down yet

Chair Powell made clear that the Fed is not backing off rate hikes anytime soon.

He emphasized that its 2% inflation target is unconditional, arguing that price stability is a pre-condition for broader macro stability. That is true in the long run, but it does not address the implication of a recession.

We see the Fed hiking rates by year end, before it is surprised by the economic damage and then stops.

ECB is just as determined as the Fed

The European Central Bank is just as set on fighting inflation but has more explicitly embraced the higher-volatility regime.

The ECB should stop hiking by the end of 2022 as it faces an energy crisis-driven recession.

Steadfast hiking cycles amid a new regime are a recipe for volatility.

We see the need for more frequent changes to our strategic views and portfolios in this new regime.

Stocks aren’t pricing the earnings downgrade and recession risk. That’s why we are underweight developed market equities now and didn’t buy the dip. But in the long term, we still prefer stocks over government bonds.

_________

We’ve argued for a while that we’re in a new macro regime. Central bankers at the recent Jackson Hole forum started to recognize this reality. But we think they’re not prioritizing economic implications over pressure to curb inflation. It seems they do not intend, for now, to manage the sharp trade-off between inflation and growth. That’s a big deal. We think getting inflation back to central bank targets means crushing demand with a recession. That’s bad news for risk assets in the near term.

Mind the growth gap

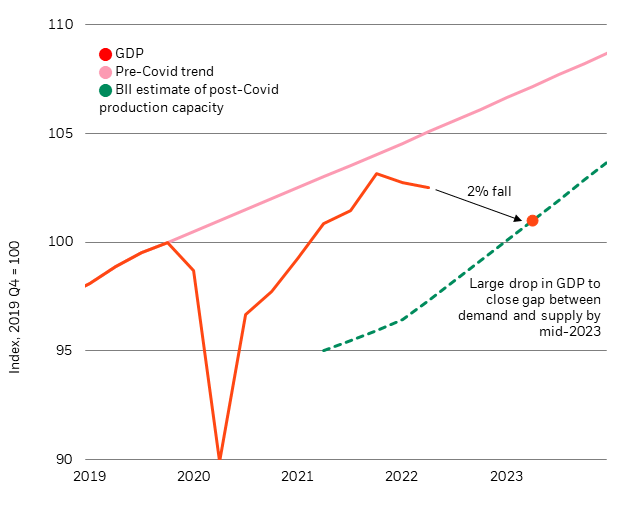

U.S. GDP And Production Capacity, 2019-2024 (BlackRock Investment Institute and U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, with data from Haver Analytics, August 2022)

Notes: The chart shows demand in the economy, measured by real GDP (in orange), and our projection of pre-Covid trend growth (in pink). The green dotted line shows our estimate of current production capacity. We infer that from how far core PCE inflation has exceeded the Federal Reserve’s 2% inflation target.

The U.S. economy has already stalled. Now we see recession in the cards early next year. Powell made abundantly clear at Jackson Hole that the Fed has, for now, no intention of backing off its hiking cycle. The problem is that rate rises won’t solve the biggest issue: low production capacity (see green dotted line in chart). The only way the Fed can get inflation down quickly is by raising rates high enough to force demand (orange line) down by around 2% to what the economy can comfortably produce now. That’s well below the pre-Covid growth trend (pink line). But the Fed has yet to acknowledge the great cost to growth or the unusual nature of constraints in the labor market since the pandemic. We estimate 3 million more people would be unemployed if demand were to contract by 2%.

The Fed will be surprised by the growth damage caused by its tightening, in our view. When the Fed sees this pain, we think it will stop raising rates. It will be too late to avoid a contraction in economic activity by then, we think, but the decrease won’t be deep enough to bring PCE inflation down to the Fed’s target of 2%. Instead, we expect inflation to persist close to 3%.

The outlook for Europe

Europe is a different story; we’ve expected recession there for months given the energy crunch. By year end, rate rises will push the euro area into a deeper recession. The European Central Bank (ECB) appears just as determined as the Fed to fight inflation by raising rates. At Jackson Hole, ECB executive board member Isabel Schnabel acknowledged a trade-off between taming inflation and maintaining growth. Yet, she stressed a “robust control” approach to monetary policy, focused on getting inflation down at whatever cost. We think the ECB will hike 0.75% on September 8. But like the Fed, the ECB is not grasping the full extent of the recession needed to crush inflation, in our view. We think the ECB will keep raising rates through the rest of the year, but stop earlier and well short of market projections when faced with the gravity of the recession.

What this means for investing

The main conclusion: the new regime requires more frequent adjustments to portfolios. Time horizon is also key. In the short term, we’re underweight developed market (DM) equities on a worsening macro outlook. Central banks look set to overtighten policy and stall the economic restart. The recessions we predict are not priced into equities, we think. That’s why we aren’t buying the dip. Longer term, we’re modestly overweight DM equities. They have relative appeal over private growth assets – those have yet to reprice like their public counterparts – and fixed income, where we see higher yields dragging on expected returns. Sectors that we believe will benefit most from long-term trends like the net-zero transition, such as technology, are also particularly well-represented in the DM equity universe.

Publicly traded credit is an overweight in our strategic portfolios for the first time in years as yields and spreads have materially repriced. That includes high yield. Tactically, we prefer to be up in quality in investment grade, since we think it could better weather a slowdown that equities haven’t priced in yet. Lastly, we’re overweight global inflation-linked bonds, now and even more so further out. Why? We think markets are once again underappreciating the persistence of higher inflation. We’ve been arguing all year we’re in a new regime of heightened macro volatility driven by production constraints. In the near term, they are caused by Covid supply disruptions and labor shortages. In the long run, we see them pressured by structural forces such as a bumpy net-zero transition and a rewiring of global supply chains amid geopolitical tensions.

Market backdrop

Stocks ended lower in a volatile week after Powell’s hawkish Jackson Hole comments about the Fed’s “unconditional” objective to bring inflation back down to its 2% target. On Friday, U.S. jobs data showed another month of job gains alongside an increase in those searching for jobs. Given Powell’s tone, we see the Fed hiking through this year and think it will only stop tightening once it sees the damage to growth and jobs from higher rates.

The ECB will be the center of attention this week, and we expect it to raise rates by 0.75%. An ECB executive board member’s comments at Jackson Hole suggest the central bank is starting to acknowledge that reducing inflation to its 2% target will come at a sizable cost to jobs and growth. We’ll be assessing how much that’s reflected in the ECB’s updated forecasts. We see the ECB hiking rates through 2022 and then stopping amid an energy shock-triggered recession.

Be the first to comment