Petmal/iStock via Getty Images

The environmental factors (E) in ESG are dominated by measures of carbon emissions, energy and net zero, but less attention is paid to the use of materials and waste. This, in turn, is reflected in the relatively poor quality of data and associated metrics on waste and recycling referenced in corporate sustainability reports.

This is a problem, particularly given the higher costs of raw materials and energy, and greater regulatory oversight on waste. This data deficiency also deflects from the significant level of carbon emissions linked to the way material is handled and used.

As pressure increases on companies to improve the quality and consistency of ESG data and on financial institutions to move beyond superficial sustainability engagement, it is time for a sharper focus on waste management and recycling.

If companies are to publish higher-quality, validated and comparable data on their waste and recycling performance, they need to gain more insight into the processes and commercial models associated with the production, movement and processing of material.

Only then can financial markets generate meaningful, comparable metrics and companies generate actionable insights that can drive greater cost and resource efficiencies, validate compliance and increase corporate value.

Over the past five years, ESG factors have moved from a minor role to a lead act, albeit in some cases with mixed reviews. Understandably, critical reviews cite the variability in standards, analysis and metrics. This partly reflects the relative immaturity of ESG considerations, as well as the variance and depth of understanding across the many themes addressed in sustainability strategies.

While the environmental strand is dominated by carbon emission, energy and net zero considerations, less attention has been paid to materials and waste, whether it is created by industry, services, retail, property, construction or households.

In many ways, waste has been normalised as a cost of doing business – we buy raw materials (some of which are wasted), we convert them to products (creating operational by-products), we distribute and sell the products (creating waste in transit) and then dispose of products and packaging after use.

This ‘linear’ economic model is now being challenged by government policy, increased supply chain pressures and rising costs, shifting the focus to a ‘circular’ economy. However, to realise the benefits of transitioning to a new economic model, there remains a need to obtain greater visibility and understanding of what happens to waste.

Waste generation nearly doubled between 1970 and 2000[1] and continues to grow exponentially. The World Bank estimates that waste generated in urban areas will total 3.4bn tonnes per year by 2040. Currently, more than 60% of this material is sent to landfill and more than 61% of the world’s population does not have access to recycling infrastructure, which creates significant economic loss, social problems and environmental danger.

These rising levels of waste are also linked to the rapid growth in consumption. The 2022 Circularity Gap Report notes that more than 90% of the materials extracted and used to make products and packaging ultimately become waste. In essence, only 8.6% of these materials are fed back into the production system.

This is poor from a resource efficiency perspective but perhaps more so in relation to the climate, given approximately 70% of global greenhouse gas emissions are linked to the way material is handled and used.

The full social cost of these emissions is not accounted for in the production and consumption decisions which lead to the generation of the waste, or in how that waste is managed. Ensuring that the amount of waste is reduced to an economically efficient and environmentally viable level will ensure that associated policies deliver net benefits for society as a whole.

The pandemic, extreme weather events and other geopolitical shifts have brought company supply chains into sharp focus. Effective, transparent and sustainable supply chains have a positive impact on enterprise value as companies focus on effective sourcing, resource and cost efficiency and a reduction in environmental and carbon impacts.

The focus on waste and materials will grow significantly over the next five years through a range of factors including cost pressures and more regulations, for example digital waste tracking or taxes on plastics. Furthermore, companies accessing capital markets will be expected to improve the quality and consistency of data, disclosure and reporting. This applies equally to their approach to waste management and recycling.

Globally, publicly available waste management data is usually drawn from national regulators and agencies. These, in turn, require commercial waste companies and municipal authorities to disclose data on a regular basis. The quality of this data is by its nature varied because the $1.6tn industry that manages and processes this material ranges from multinational corporations to informal community enterprises.

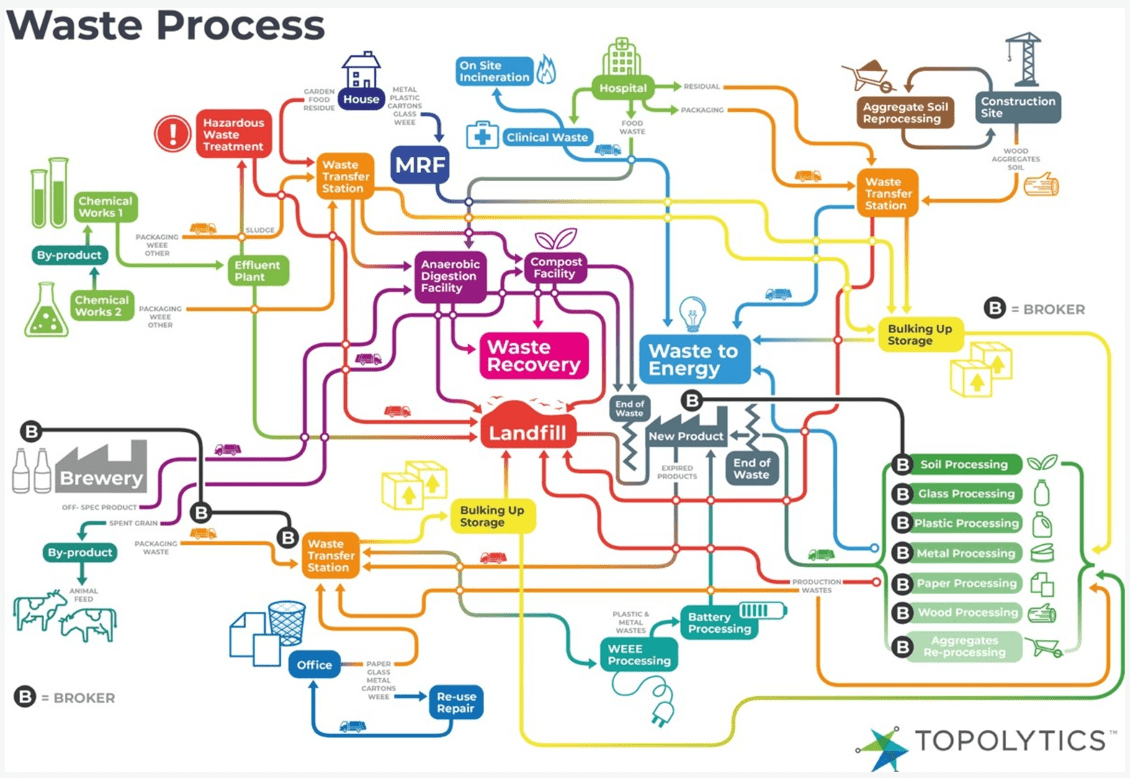

A key global challenge is the ability to monitor the billions of material movements annually, from hazardous sludges, through construction waste, inert recyclables (such as plastics and card), metals, organics/food and ‘special’[2] waste materials from industrial processes.

This opaque and inconsistent picture is an acknowledged problem, but without this data and the analytical opportunities it presents, the outcomes will not be optimal and the significant value in waste materials or by-products will not be realised.

This issue is not unique to waste – many ESG factors face similar limitations with respect to data that can vary considerably depending on region, sector, size or indeed regulatory structures.

[1] United Nations Environment Programme and International Solid Waste Association, 2015

[2] Special waste materials have hazardous properties that may render them harmful to human health or the environment.

Waste processing: A challenge to collect reliable data (Source: Topolytics)

If the data across the waste system is highly variable, siloed and often questionable or non-existent, as it undeniably is, it calls into question the quality of data that is fed into ESG reports, even where they reference the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) guidelines or the Sustainable Accounting Standards Board/Value Reporting Foundation.

According to a recent study, 79% of UK 100 companies reported on their sustainability governance and performance, with 85% and 86% reporting on waste management and emissions reductions respectively. The reporting standards have evolved the approach to waste, for example the GRI updated its guidance in 2020, refining the definitions.

Waste is now more prominent in the ‘E’ of ESG reports and our experience indicates the reasons why:

- A sharpened focus on materials supply and costs – linked to efficient use of materials and resources.

- The drive for net zero, which is pushing companies to measure and reduce impact, particularly across their supply chains.

- The growing number of policies and regulations focused on recycling, extended producer responsibility, landfill bans and circular economy.

- Heightened interest in and focus on corporate transparency and honesty – no greenwashing here!

- Growing demands from investors for better, more comparable, standardised data on ESG metrics.

If we drill into waste and recycling as a sustainability ‘issue’, there are a number of key challenges facing corporate reporters. Firstly, waste management companies define and measure waste differently (despite the presence of classification schemes).

They also collect, store and process this data in different ways, which means there is a tremendous variety in the reports presented to customers and an inherent level of opacity. Corporate reporters therefore have poor or limited visibility of this downstream supply chain and restricted knowledge of what happens to their waste.

In parallel, the way waste is regulated also varies across countries and within countries. For example, there is some variation in waste permitting and licensing systems across the four UK national regulators, as well as other procedural and data differences. Consequently, there is a need for data harmonisation and standardisation across the regulatory and commercial waste system, including the UK.

Secondly, and related to the first point, the end-to-end movement of waste through the system is not visible to any participant in this value chain – from the waste producer through the carriers and processors.

For certain materials, this chain of custody may be simple and robust, but in most instances the material moves through a series of sites, ownerships and transformations before reaching the end of its journey. Here it may be sent to landfill, incinerated, recycled and recovered or leaks from the system in its country of origin or exported.

While this complexity, opacity and variety across the waste system is not unique, when looking at other ESG metrics, it is particularly challenging compared to measuring the use of materials, water or energy, where there is a much greater focus on purchasing and limited transformation in the supply chain.

The chimerical nature of waste makes it difficult to assess in a quantitative way, specific to set metrics, so as a factor it is often marginalised or incorporated into other metrics qualitatively because it is difficult to ascribe materiality to as a separate entity with any real certainty.

As corporate waste producers and the waste industry adapt to a policy environment dominated by waste reduction and circularity, there is a need for new infrastructure and business models.

The system may well become more decentralised and distributed and waste producers will want to exert more control over measurement and management as they seek to understand what happens to their waste, and drive elimination and re-use of products and materials.

Industry 4.0 technologies will also play a part, with bin sensors, smart labels, robotics and machine vision systems collecting data across parts of the system and across certain materials, particularly packaging.

However, these technologies will only measure parts of the overall system, so the ability to make sense of multiple systems and data sources will remain vital, even in the context of a corporate reporter’s waste management picture.

Waste has strong links to a range of other issues within the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, such as health, climate change, poverty reduction, food and resource security, as well as sustainable production and consumption.

For financial institutions, the case for understanding waste as an entry point for other issues is incredibly important for the ability to assess potential risks and opportunities accurately. Solid waste, liquid effluent or air emissions reflect the incomplete, inefficient or ineffective conversion and use of raw materials inputs.

In addition, companies are incurring costs that do not generate value, by handling, storing and disposing of waste and by-products. At a societal level, waste also reflects a loss of biodiversity, as well as feeding a rise in man-made carbon emissions.

Ultimately, waste is a by-product of economic activity by businesses, government and households. However, it is also an input to economic activity – whether through recycled material or refuse-derived fuel. Its management therefore has real economic implications – for productivity, government expenditure and, of course, the environment.

But it is not homogenous or easily categorised. Waste is a physical material (asset) that is created in one location then moved for storage, transfer, sale, processing, disposal or reuse. This is a complex picture physically, commercially and geographically.

If waste and recycling data and measures in ESG reports are to be trusted, it requires an understanding of the processes and commercial models associated with the production, movement and processing of the material.

This in turn requires the ability to access, process, standardise and analyse data from many sources in different formats. Only then can it be distilled and visualised to generate meaningful, comparable metrics that can feed into reporting and actionable insights, which can drive greater resource efficiency and recovery.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors

Be the first to comment