Torsten Asmus/iStock via Getty Images

Transcript

Government bonds: Not recession-proof

Historically, government bonds behaved as safe assets during recessions as central banks would ease policy, but we think this time is different.

We flag two reasons why we stay underweight the asset class.

1) Bond yields to run higher

First, we believe government bond yields still have room to run higher.

This new environment of high inflation and raising rates may break the fragile equilibrium where investors tolerated surging debt loads without more compensation.

The UK has provided a proof point. Long-term gilt yields have spiked, reflecting a revival of term premium or the compensation investors demand for holding longer-term bonds.

2) Bonds no longer a safe haven

We see recession before inflation gets under control and before central banks stop rate hikes.

Case in point: Recession risks are clear in the UK, yet the Bank of England appears nowhere close to stopping rate hikes.

Clearly, this is not a context for UK government bonds to be a safe haven.

Here’s our market take…

In this new era of highly volatile economic and market conditions, we prefer short-dated maturities within a broad underweight on nominal government bonds.

We also like inflation-linked bonds and high-quality credit.

____________

Recession fears are roiling markets. Investors traditionally take cover in sovereign bonds, but we see this recession playbook as obsolete. Why? First, central banks are hiking rates to try to tame inflation, causing recessions. Second, we don’t see them cutting rates like they typically do in recessions due to persistent inflation. Third, we expect investors to demand more compensation for the risk of holding government bonds amid high debt loads. Result: We stay underweight Treasuries.

UK yields a glimpse of the future

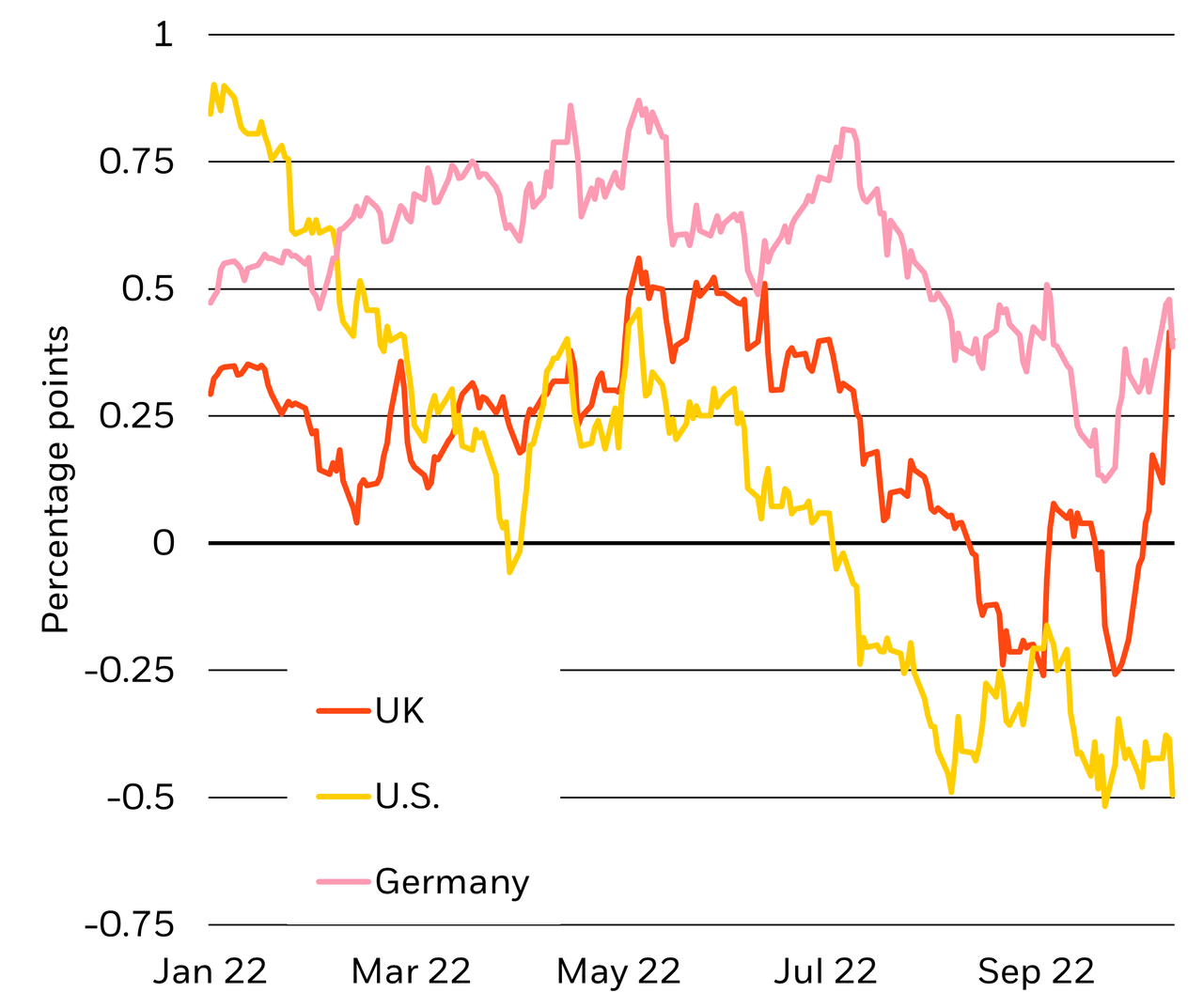

Government bond yield curves, January-October 2022 (BlackRock Investment Institute, with data from Refinitiv Datastream, October 2022)

The chart shows the yield spread as measured by the 10-year bond yield minus the two-year bond yield in the following countries: U.S. (yellow line), UK (orange) and Germany (pink line).

In the Great Moderation, a period of steady growth and inflation, central banks would have eased policy on signs of contracting growth. That era is over. Now central banks are set to induce recessions by overtightening policy. In this supply-driven recession, high inflation and rising rates may break the fragile equilibrium where investors tolerated surging debt loads and forwent a higher term premium, or compensation for the risk of holding long-term bonds. The UK offers a glimpse of this. Long-missing bond vigilantes are back as markets question UK macro policy credibility. And financial dislocations have accelerated and amplified the move. The difference between 10-year and two-year gilt yields (orange line in chart) has surged. Yet yield curve moves of German bunds (pink) and Treasuries (yellow) show a muted response not yet pricing in a higher term premium.

We see long-term yields rising across developed markets. Why? Policy, inflation and debt. Central banks in the new regime face a sharper trade-off between growth and inflation than in the past. Yet, their forecasts, as well as the International Monetary Fund’s update last week, aren’t acknowledging that the cost of bringing inflation down to targets is triggering recession, in our view. We think central banks will eventually halt rate hikes. But they won’t have done enough to get inflation all the way back down to target, implying they won’t be able to start easing policy, in our view. Higher policy rates and inflation create a ripe environment for investors to demand higher term premia for long-term bonds.

UK proof point

All of this underscores why the old recession safe haven playbook doesn’t apply. That’s no mere musing: we see it playing out in the UK in real time. The energy crisis had already put the UK on the brink of recession. The Bank of England (BoE) could exacerbate the pain by hiking rates even more than originally expected to offset fiscal stimulus. Backlash to the planned stimulus has sparked a gilts selloff and led to the finance minister’s resignation. The BoE’s two-week buying of long-term bonds helped briefly drag down yields, but they spiked anew as the program ended last week. While the government has trimmed its tax cut plans, they have already dented UK fiscal credibility and would still add to the debt build-up during the Covid-19 shock. In this environment, bond vigilantes are back and heralding term premium’s return.

Our bottom line

We’re broadly underweight government bonds. U.S. bond returns are the most positively correlated to stocks in two decades on a 90-day rolling basis. We expect that correlation to stay positive, erasing bonds’ role as portfolio diversifiers. We don’t think long-term yields reflect the likely persistence of inflation and higher term premia coming as a result. Higher short-term rates also make the long end less attractive because investors can get decent returns in short-dated bonds with less interest rate risk. We stay underweight U.S. Treasuries. Policy rates would need to hold steady or fall for Treasury returns to flip positive, we find. We previously cut UK gilts to underweight on fiscal credibility concerns. We’re neutral on euro area bonds as we think expectations for European Central Bank rate hikes are too hawkish. But we’re underweight Italian bonds. Italy shares some of the UK’s vulnerabilities – worsening fundamentals from a current account deficit and a heavy debt burden.

Strategically, we’re underweight developed market government bonds and see yields higher in five years and beyond. We prefer inflation-linked bonds both tactically and strategically given they are not pricing in persistent inflation. We like high-quality credit: strong corporate balance sheets should limit default risks even in a recession, in our view.

Market backdrop

Stocks fell and short-term U.S. Treasury yields hit 15-year highs, further inverting the yield curve, after the U.S. core CPI hit a 40-year high of 6.6%. We think this shows that the U.S. economy is running above its constrained production capacity, including the labor market, reinforcing the Fed’s singular focus on price pressures. We see the Fed overtightening policy and only stopping when confronted with the economic damage of its rate hikes in 2023.

Markets will turn to China’s monthly data to gauge how the economy is holding up given ongoing Covid-related restrictions. The UK’s CPI should confirm inflation is staying sticky. While the UK fiscal drama has been the main focus, any fiscal stimulus could push the Bank of England toward more rate hikes despite signs the economy is starting to contract.

Be the first to comment