RCKeller/iStock via Getty Images

It doesn’t look pretty

Today’s Investors face challenges that never occurred during the last 40 years of financial markets:

The global economy is slowing down rapidly. Political conflicts spur deglobalization and polarization. Central Banks are caught between a rock and a hard place. Most of the demographic forecast of the West looks like inverse Egyptian architecture. Private and public debt levels of western countries exceed the historical norm. All the while, credit availability shrinks drastically. Energy is structurally undersupplied. Thus input costs soar, and margins get squeezed.

Stock/Bond correlation is at an all-time high. The 60/40 portfolio got slaughtered in 2022. Central Banks, led by the Federal Reserve are raising interest rates while selling bonds to rein consumer price inflation by tightening credit markets and deflating asset prices. Thus, precious metals continue their sell-off due to increasing positive real rates. The energy sector looks better fundamentally but remains elevated and still prone to demand destruction.

A historical comparison to the longest bull market in history

If we want to have a clear and honest view of the current situation and how it went wrong, we have to look at what went right during the longest bull market in history, from 1982-2021. Many of the most significant macroeconomic circumstances that have driven the historic bull market have flipped negative during the recent two years.

1. Disinflation

Falling inflation lowers interest rates and therefore borrowing costs for the private sector, companies, and the government. Continuously lowering borrowing costs increase credit demand and stimulate the economy, which is ultimately bullish for the market. The rate of change of the disinflation is much more important than the nominal level of inflation, as long as the inflation itself doesn’t create dysfunctional markets. While nominal inflation in 1982 was still high, it continued to trend lower during the following 40 years in a behaved and predictable manner:

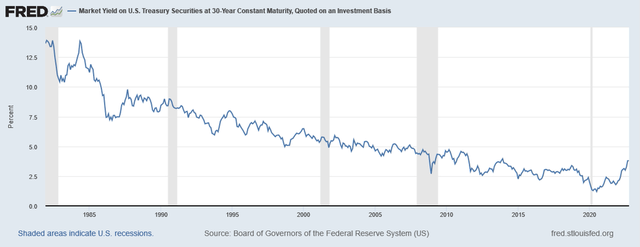

Market Yield on 30Y US Treasuries (fred.stlouisfed.org)

In March 2020, the 30-year US Treasury yield briefly touched 1% at the low point. However, the soaring inflation, which originated partly from the huge expansive and coordinated monetary and fiscal policy after the Covid shock in 2020, broke the positive downward spiral of disinflation. The 30-year US Treasury yield is currently at 3.81% and broke the highs of late 2018.

2. Globalization

Globalization and outsourcing spread during the last 40 years, reducing input costs for companies because they could access cheap labor abroad. Globalization led to the rise of the biggest manufacturer in the world: China. Just-in-time deliveries reduced storage costs, and specialization increased productivity. Due to the technological advance originating from specialization, the same amount of money could buy more advanced goods, increasing the average purchasing power of the consumer. All in all, globalization was the great deflationary force that kept the lid on inflationary pressures due to higher levels of economic growth.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing rivalry between the USA and China signal a tipping point in an almost fully globalized world economy. Companies and governments have started to value the stability of their supply chains much higher than in previous peace times. In an upcoming bipolar world, which isn’t clearly dominated by one economic and military power, more spending on infrastructure and defense will be needed because the world is lacking the efficiencies of specialization and trust. Deglobalization will come with structurally higher inflation and reduced economic efficiencies.

3. Demographics

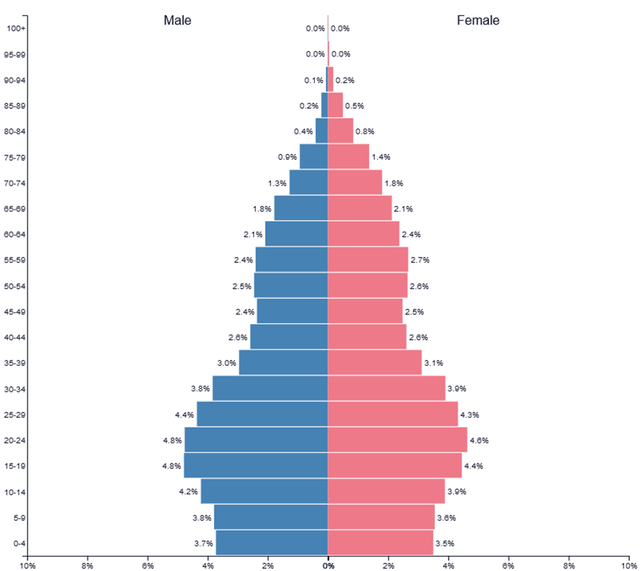

Starting in the 1980s, the Baby Boomers entered the workforce in their early 20s and contributed to major economic growth after WW2. Labor Unions in most western countries had a strong standing initially but, their influence lessened over the following years because of the unusually high percentage of workers and the resulting competitiveness of the labor market.

US Population Pyramid in 1980 (populationpyramid.net)

After working for half of their life (~40 years), most of the Baby-Boomers have already or will soon hit their retirement age. They will become economically unproductive for 20-30 years and slow down economic growth the same way they accelerated it 40 years ago. Additionally, there are too few workers to replace the retirees. Therefore, wages should rise on average. This should increase the inflationary pressures if the global economy remains on a comparable level. However, the downturn in spending because of the retirees should have a deflationary effect.

4. Costs of energy and commodities

Energy and commodity supplies were abundant after the 1980s, in relative terms. High-quality, easily accessible reserves were available and technological advances in mining and energy extraction decreased input costs. The disinflationary force of low input costs was prolonged by the shale revolution post-2008.

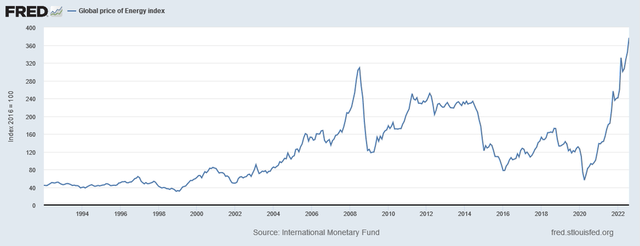

In 2022, the global price of energy hit a new all-time high:

Global price of Energy Index (fred.stlouisfed.org)

Commodity and energy producers face a vastly different environment nowadays. Fewer reserves are easily accessible, and investments in the traditional energy sector are sabotaged by ESG mandates and environmental activists. The socially demanded shift towards green energy is the first time for humanity to ever attempt switching towards a less dense energy source than used prior.

The side effect will be structurally higher prices for energy even if prices come down from current highs due to a decrease in global demand. Over the long term, this will lead to permanently higher input costs which will likely squeeze margins for companies, making them less profitable and less likely to repurchase their own shares.

5. Global debt levels

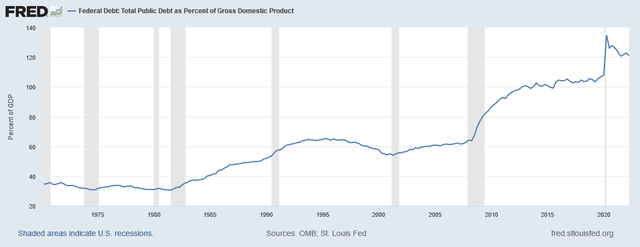

The debt to GDP ratio in 1981 was the lowest it has been in modern America. From 1981 to 2020, debt to GDP expanded from 30% to 120%, subsequently with continuously lower interest rates to service that debt. As interest rates rise, servicing the vastly higher debt levels of the public (but also private) sector will put increased stress on the global economic outlook.

Total Public Debt as Percentage of GDP (fred.stlouisfed.org)

In a Nutshell:

| 1982-2021 | Going Forward: | |

| Inflation Rates | Falling | Rising |

| Globalization | Spreading | Stagnating |

| Demographics | Young | Old |

| Relative Energy Costs | Low | High |

| Debt Levels | Low | High |

The last 40 years of financial markets had vastly different underlying macroeconomic circumstances. Let’s take a look at how these macroeconomic factors could affect the reaction function of the Federal Reserve and the potential markets of the future.

Why a Market Crash is likely to happen first

Because the Federal Reserve has de-facto control over the risk-free rate of the global reserve currency, it can dictate the global monetary policy on its own. By raising rates and pursuing Quantitative Tightening, with the intention to weaken the US labor market and to crush demand via the reverse wealth effect, the value of the US-Dollar rises.

The resulting weakening of demand should lead to less consumer price inflation while assets deflate. However, other Central banks have to keep up with these restrictive policies. If they don’t, or worse can’t because their regional debt service costs and expansive fiscal policy would be too expensive, the pressure will be released through the foreign exchange rates of the respective currency. That’s exactly what happened with the Euro, the Pound (!), and the Yen. It will continue until the Federal Reserve pivots or foreign central banks tighten monetary policy as much as the Federal Reserve dictates.

The Federal Reserve policy will change if either the threat of consumer price inflation has vanished or if the pain of tighter monetary policy is too high to bear – i.e. if something “breaks”. In my belief, the chances of core CPI returning to the policy goal of 2% is unlikely without a major slowdown of the global economy, which would likely result in a market crash. Especially because of the newly established structural inflationary pressures that result from deglobalization and energy shortages.

We already see disorderly moves in some bond markets (e.g. UK gilts), but that didn’t stop the Federal Reserve from continuing the tightening of financial conditions. In general the Federal Reserve seems to be focused solely on regaining credibility by taming US consumer price inflation. The tightening has progressed, but I only believe it’s over until the Federal Reserve says so.

Interestingly, if the market raises the implied chance of a Federal Reserve pivot and interest rates fall in anticipation of that event (e.g. July 2022), financial conditions loosen, and the Federal Reserve has room for even more tightening. We likely need to see serious “breaking” of US markets, whatever that might be: treasuries, repo facilities, or my personal favorite: the labor market. There is no point in reading tea leaves. If the markets break, everyone will know. The panic, the liquidations, and the Federal Reserve pivot will be obvious. The US-Dollar is the safe haven until then.

Why a Fiat Crisis could follow

Let’s suppose the market “breaks” in some shape or form. Asset prices collapse, and the Federal Reserve has to pivot in order to fix the disorderly market. The Dollar would devalue instantly while yields would fall, and the “rising US-Dollar burden” on foreign currencies would be lifted. Asset prices would stabilize after the shock and move slowly upwards. Financial conditions would ease, and credit growth would accelerate. The global economy would recover after some time.

Sounds familiar right? That’s basically what happened during every major crisis between 1982 and 2021. Except, now the Federal Reserve pivot has one distinct change of effects: additional consumer price inflation.

Because of the structural changes in the global economy, consumer price inflation should come back sharply after the Federal Reserve pivot. It is likely that fiscal authorities never stopped spending money in the first place. Even if they did stop because debt servicing costs were too high, then they’d likely restart their fiscal deficit programs because the economy is still in major pain. The combination of expansive monetary and fiscal policy during times of energy shortages, deglobalization, and war will ultimately result in another spike in consumer price inflation, and fiat money in general would devalue. The Dollar would be no exception now.

The rising inflation would trigger another round of monetary tightening thus another bear market, another run-up in the US-Dollar, creating a vicious cycle. Nominal asset prices would likely not go anywhere for years until a large portion of the debt is inflated away, and interest rates could stay higher for a sustained period of time without causing too much financial distress. Staying in cash doesn’t seem better in that scenario.

What to do? Closing thoughts

The current environment isn’t something for your “long-only have no clue about the market but diversified” friend – everybody has at least one of them. While the macroeconomic factors were perfect to Dollar-Cost-Average and Buy-the-Dip in global financial markets from 1982 to 2021, this environment has likely changed for a prolonged period. After the unstable macroeconomic circumstances are sorted out, I’m happily converting to being a passive investing long-only ETF disciple.

Cash can’t be a safe haven because the Federal Reserve pivot will come at some point, and consumer price inflation will likely remain elevated or reemerge. Cash has been the best asset during times of Federal Reserve tightening however. In my opinion, recurring cash flows in form of dividend-paying stocks (e.g. the Energy Sector) are also likely going to outperform during a long-term sideways market, with big boom and bust cycles.

Especially Hedge Funds are outperforming the market again after decades of underperformance relative to beta-farming long-only index fund investors. Timing the market may work wonders again but will require some expertise.

Be the first to comment