DNY59

This article was first released to Systematic Income subscribers and free trials on July 20.

In this article we discuss the recent distribution suspension / reinstatement of the Virtus Convertible & Income Fund II (NYSE:NCZ). A discussion of this recent event also gives us a chance to review some key CEF concepts that we haven’t touched on since Q1 of 2020. These concepts are important for investors who want to understand the mechanics of CEFs, particularly in periods of stress such as the one we are going through now.

What Just Happened?

On 1-July NCZ issued a press release stating they have postponed the payment of the distribution that was due to be paid on the same day. They also postponed the declaration of the distribution that was due to be declared on 1-July and paid on 1-Aug. Then on 8-July NCZ issued another press release where they said they will pay the distribution originally set for 1-July and also declared the distribution set to be paid on 1-Aug.

Why Has This Happened?

To understand why the fund has had to suspend its distribution we need to look at three separate things. The first is the regulatory reason which, according to the Investment Company Act of 1940, prevents CEFs from making distributions if the asset coverage of preferred securities is below 200%. Asset coverage of preferred securities takes total assets and divides it by the sum of all senior securities i.e. all outstanding preferreds and public debt.

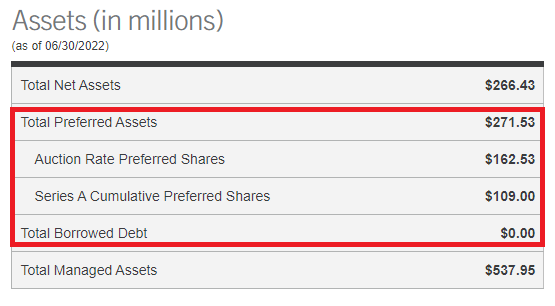

For reference, the fund’s liability profile is made up entirely of 2 preferreds: an exchange traded Series A (NRZ.PA) and an auction-rate preferred.

NCZ

For a fund that sources its leverage completely from preferred securities having preferreds asset coverage fall below 200% is, via 3rd-grade algebra, equivalent to leverage rising above 50%. In short, if NCZ leverage rises above 50% it is not allowed to make distributions on common shares (it is allowed to make distributions on preferred shares, however). As it happens, it is also not allowed to buy back its common shares or issue additional preferreds – two things that would increase leverage i.e. decrease asset coverage of the preferreds.

However, we need to be careful to conclude that leverage rising above 50% would cause all CEFs to suspend distributions which is far from the case. To understand why we need to distinguish between three types of CEF leverage: regulatory, effective / structural and economic / portfolio.

Regulatory leverage is public debt and preferreds. A handful of funds such as the CLO Equity CEFs have publicly traded debt. A few dozen have preferreds, including the pair NCZ and NCV. There is a lack of clarity whether private / bilateral debt such as bank credit facilities count as regulatory debt or not. Nuveen appears to consider credit facilities as falling under regulatory leverage whereas Ares (e.g. ARDC) does not.

Effective / structural leverage looks and acts like regulatory debt but isn’t. It can include things like repo and tender option bonds (as well as credit facilities on which there is disagreement as mentioned above). A fund that sources its leverage via repo such as the taxable PIMCO funds would have no problem seeing its leverage rise above 50% and carry on making distributions on common shares.

Economic leverage are derivatives like futures, credit default swaps, equity total return swaps and others that synthetically provide similar economic exposure to cash assets but have no real dollar footprint in the fund’s assets. For example, a $100m S&P 500 total return swap can have a negligible mark-to-market whereas $100m worth of S&P ETF or individual stocks would have a $100m footprint. In short, economic leverage can allow the fund to achieve the same economic exposure without having an impact on the fund’s total assets or its leverage metric. Economic leverage has no impact on the fund’s ability to make distributions on common shares.

To sum up, in order to make distributions on common shares a given fund has to have at least 300% asset coverage on its public debt and at least 200% asset coverage of its preferreds. NCZ failed the latter test and, hence, wasn’t able to make a distribution on 1-June.

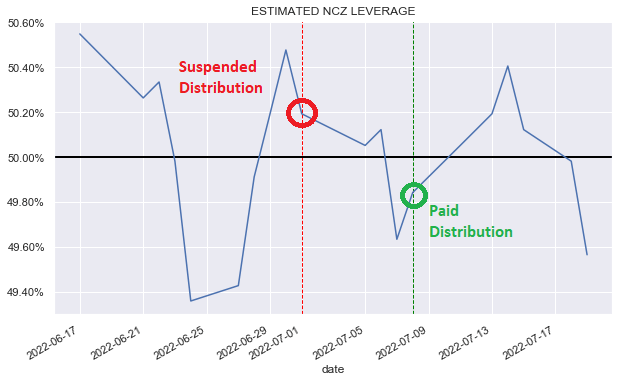

In this chart we plot the fund’s daily leverage level and can see that on 1-July the fund’s leverage was around 50.2% i.e. its asset coverage was below 200% and therefore the fund could not pay a distribution. Once leverage fell below 50% the fund could pay it out. As of this writing the fund’s leverage is below 50% and, if it remains the case, will allow it to make its August distribution.

Systematic Income

The second markets-based reason the fund was not able to make its distribution has to do with the fact that the fund 1) has tended to operate at a relatively high leverage level, 2) has a high-beta portfolio and 3) has a relatively high distribution rate.

For instance, during “normal” periods NCZ has tended to run at leverage of around 40% which is well above the typical taxable CEF sweet spot of 30-35%.

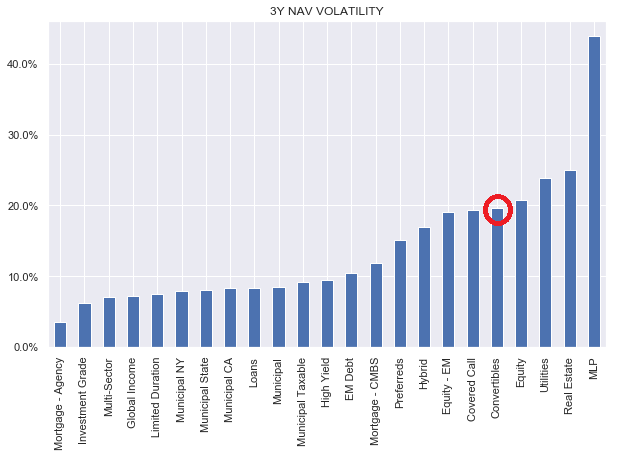

The fund also holds convertible bonds for a bit more than half of its portfolios (the rest being high-yield corporate bonds). As the following chart shows, convertible debt CEFs (most of which are actually not pure-play convertible bonds which understates the high volatility of converts) have an elevated volatility in the CEF space.

Systematic Income

Finally, the fund’s high distribution rate (which is in excess of its income profile) means its NAV will tend to deflate over time, mechanically raising its leverage level (because total assets decrease while borrowings remain the same) and making it easier for the fund’s leverage to rise above 50%.

The third practical reason why NCZ had to suspend its distribution has to do with the basic fact that deleveraging a fund that sources its leverage exclusively from preferreds is actually not trivial. NCZ would have to buy back their exchange-traded preferreds in a fairly illiquid secondary market (NCZ-A trades about 4k shares a day or around $100k of “par” value) or via an official repurchase announcement. The key point here is that even if NCZ wanted to deleverage in order to make the distribution payment it couldn’t have done it because of the low liquidity in the secondary market. The repurchase announcement would take time and may not result in a significant uptake anyway as many investors would be happy sitting on their shares (or away on the golf course to pay attention to corporate actions sent by their brokerage).

Why Hasn’t NCV Suspended Its Distribution?

As many investors know, NCZ has a sister fund, Virtus Convertible & Income Fund (NCV), which is very similar to NCZ.

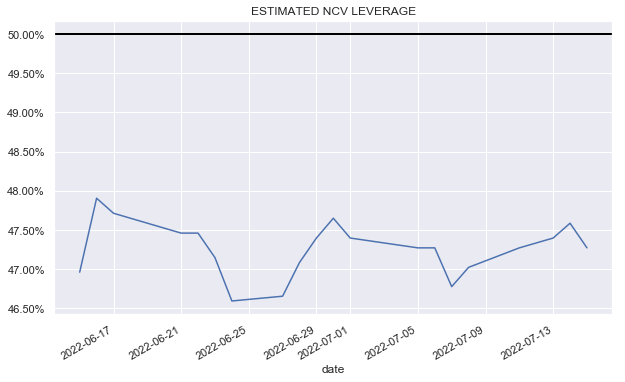

NCV has not suspended its distribution for two reasons. First, NCV has tended to run at a slightly lower leverage level historically than NCZ of about 1%.

The other reason is that NCV, in addition to its exchange-traded (NCV.PA) and auction-rate preferred, historically also carried a small credit facility balance of $29m. However, if you look at its disclosure as of end of June this balance is no longer there. What this tells us is that NCV has deleveraged the only way it could easily do so by reducing its credit facility to zero.

The result is that its leverage gap to NCZ has increased from about 1% to about 3%, putting it more comfortably below the 50% figure.

Systematic Income

This also highlights that deleveraging via a credit facility (or repo for that matter) is much easier than doing so via senior securities i.e. public debt or preferred securities.

Hang On, This Sounds Familiar.

Indeed it does. Investors who were paying attention to this pair of funds in 2020 know full well that NCZ also suspended its distribution in April of 2020, releasing it two weeks later.

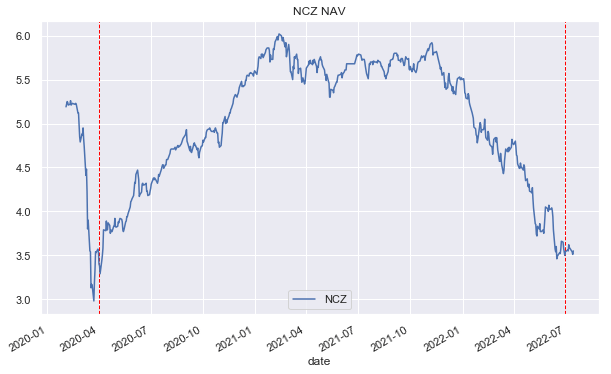

The reason was very much the same – a sharp drop in the NAV. The NCZ NAV chart is shown below with the two suspension dates highlighted. Interestingly, NCZ shows it has the same number of common shares outstanding. And since it has the same amount of debt, it makes it easy to show how nearly the same level of NAV would result in distribution suspension in both instances.

Systematic Income

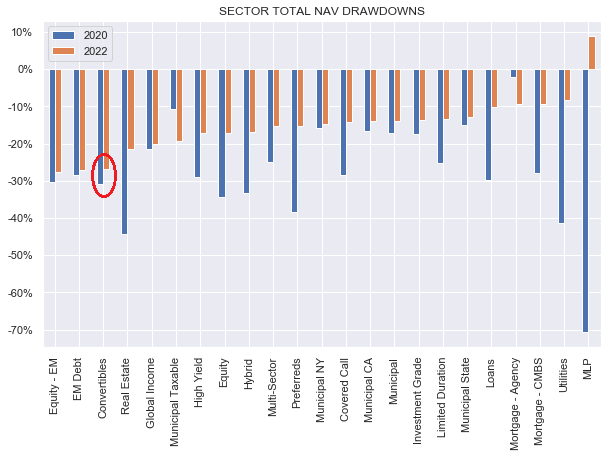

What is also very interesting is that convertible debt is one of the few sectors that has seen both a large drawdown this year and a 2022 drawdown that is similar in magnitude to the one it saw in 2020. Most other sectors, with the exception of EM Equity and EM Debt have seen either a smaller drawdown this year than converts (e.g. Muni sectors) or a similar drawdown to converts but that is smaller in magnitude than in 2020 (e.g. most credit sectors like HY). This unlucky pattern for converts is obviously linked to the broader deflation in the Tech sector which makes up a big chunk of the convertible debt space.

Systematic Income

The Suspension Sounds Bad? Is It Bad?

Whether a dividend suspension is bad or not really depends on the reasons why an investor holds the fund. An investor who holds the fund because they rely on distributions to finance their retirement will likely be put off as they would see a lower cash stream in their brokerage account.

However, investors who hold the fund because of its exposure profile are unlikely to be overly worried. Yes, distributions may have to be suspended if the fund doesn’t deleverage but nothing happens to the income the fund earns – it stays within the fund and can actually be reinvested by its managers at very attractive levels in the current market.

Retaining cash in the fund would also create an organic deleveraging as the size of total assets would grow relative to borrowings

What Are The Managers Thinking?

It’s tempting to conclude from the distribution suspension that the managers are either checked out, dumb or were somehow surprised by the move in their assets. None of these reasons really make a lot of sense to us. It’s important to understand that while some investors may hate seeing a distribution suspension, it is not strictly economically “bad” to suspend a fund’s dividend.

To understand why we only need to look at what happened in 2020. Had NCZ deleveraged at the end of March in order to avoid a suspension it would not have enjoyed as big a bounce back as it did (since it would have fewer assets to boost its return during the recovery phase). And because fixed-income markets are highly mean-reverting, a deleveraging will typically result in economic losses for investors over time. Therefore, there is a strong argument that historically the best thing to do would be to maintain the fund’s allocation profile and avoid selling assets during drawdowns.

There is obviously a limit to this argument. In a truly catastrophic drawdown (think of bank stocks during the GFC or Tech in 2000-2) an eventual deleveraging will be required to avoid leverage rising to a ludicrous level of something around 70%. However, for “normal” drawdowns avoiding a deleveraging will often result in better through-the-cycle performance for investors.

What Options Does NCZ Have?

If the fund wants to avoid another distribution suspension (again, it’s not clear to us it actually wants to avoid a suspension) then it has recourse to a repurchase plan it approved in late 2000. According to this, the fund can buy back its exchange-traded preferreds (NCZ.PA, NCV.PA) below $25 (they are indeed trading below $25) in the amount of a quarter of the daily volume (i.e. roughly $25k per day) and so long as the interest rate on its credit facility is below 5% (which it is). Interestingly, the fund has not acted on this plan, at least as of June-end.

The fund may also be able to hold a tender offer of its auction-rate preferreds as many other funds have done and, in fact, as the fund did in 2018. In fact it may make a lot of sense to do that given the interest rate on the preferreds will soon exceed the rate they can get on a credit facility. After the preferreds were downgraded, the multiplier on their interest rate rose to 200% x 7-day AA composite commercial paper. As the Fed’s policy rate rises above 3%, the ARPS will become very expensive for the two funds since the CP rate will likely track the Fed Funds rate, rising to around 6%, in an environment where credit facility and repo interest rates will be closer to 4%.

In 2018 the two funds were able to buy back 37% of the ARPS at 94% of their liquidation preference – a great result for the funds’ investors. They may still be able to do so at a discount as some investors may just want their money back (it has been locked in the ARPS because auctions have failed since the GFC, locking investor capital into the product). That said, the rise in their interest rates may not allow the funds to buy them back at a large discount.

Takeaways And Misconceptions

As usual there are some investor misconceptions as to what has happened here which are important to highlight.

The first misconception is that the distribution suspension came as a shock to investors and maybe it did but it shouldn’t have. As discussed above, NCZ suspended its distribution briefly in 2020 as well.

Another misconception is that the suspension is an embarrassment to Virtus and that management are somehow not monitoring their leverage levels. Given management also suspended the distribution in 2020 it seems very unlikely they find it embarrassing this time around as well. If it was so embarrassing this time around, they would have found it as embarrassing in 2020 and would have done something about it this year. And unlike in 2020, the fund’s portfolio asset prices have descended, more or less, in a straight line over a period of 6 months, making the element of surprise very unlikely.

Another misconception was that management should clearly have deleveraged ahead of the suspension. However, this misunderstands the ease with which a preferred can be deleveraged which is not particularly easy. It also assumes that a deleveraging was the absolute right thing to do and it’s not at all clear that it is. Those investors who are in the fund because of a conviction in its exposure profile would probably not want the fund to deleverage at all.

The final misconception has to do with leverage rules and the assumption that all funds whose leverage rises above 50% will have to suspend their distribution. This view conflates regulatory and other types of leverage. Funds like PIMCO CEFs that rely on repo (or TOBs for the Muni funds) don’t have this problem (because repo isn’t counted as regulatory leverage). PIMCO funds sometimes move above a level of 50% leverage and we haven’t heard of one suspending distributions. And that’s because their regulatory leverage is low even if their effective leverage is high.

We can argue about the pros and cons of preferreds vs repo but, arguably, NCZ is in a more resilient position than the PIMCO funds because a rise in leverage above a 50% level for a fund that sources leverage via preferreds cannot force it to deleverage whereas most other funds will have covenants on their credit facilities or repo that make sure fund leverage doesn’t rise above a certain level.

Overall, the key takeaways here are pretty simple. Investors who don’t like seeing dividend suspensions should avoid the handful of funds like NCV and NCZ that 1) only use regulatory leverage instruments, 2) run at high leverage levels, 3) have high-beta portfolios, 4) don’t tend to deleverage preemptively.

Other investors who have high conviction in the funds’ allocation profile will likely be less bothered by the suspension since it actually lowers the risk of a future deleveraging and allows the managers to reinvest the cash into attractively priced assets.

Be the first to comment