ultramarine5

The worm may have begun to turn in the banking world. Leadership may be flipping from Wall Street banks to Main Street banks (diversified banks versus investment banks if you prefer). With the exception of Goldman Sachs (GS), which has made little headway in its effort to build out its consumer banking since 2016, the relative importance of Main Street banking and investment banking is a matter of degree. In the past few years, however, the differences have had a major impact on results. To understand the present prospects within the overall category of mega-cap banks one must first fully grasp the reasons for this divergence.

Among the six mega-cap banks, Goldman and Morgan Stanley (MS) fall into the investment bank class while JPMorgan (JPM), Bank of America (BAC), Wells Fargo (NYSE:WFC), and Citigroup (C) are in the category of diversified banks. Investment banks make their money on trading, IPOs and mergers, and wealth management. JPMorgan, the most truly “diversified” bank, stands astride the two categories. Here a table I put together showing how JPM and the two banks which fall into the SA category of “investment banking and brokerage” make their money. It might be helpful to place the three banks plus BAC in perspective by understanding the absolute number in context of their market caps: JPM ($340B), BAC ($274B), MS ($150B), and GS ($105B).

| Bank | JPM | MS | GS |

| Net Interest Income (NII) | 53.3B | 9.3B | 6.8B |

| Trust Income | 20.4B | – | – |

| Brokerage Commissions | – | 5.7B | 3.6B |

| Trading | 14.9B | 12.7B | 23.1B |

| Asset Management | 20.7B | 8.3B | |

| Underwriting & Investment Banking | 10.0B | 12.7B | |

| Other | 25.6B | .8B |

BAC does not break out its non-interest income in this way, and it is clear from the above table that JPM’s approach doesn’t facilitate apples to apples comparison. What’s clear, however, is that JPMorgan is very large in the investment banking area. Its investment banking is smaller only in context of its total interest income. In fact, the largest global investment banks are JPM, GS, BAC, and MS in that order. The important comparisons of the officially labeled investment banks are in trading (where Goldman Sachs leads) and Asset Management (where Morgan Stanley leads). Goldman is larger in Underwriting and Investment Banking.

Knowing the importance of trading, underwriting, and investment banking in context of the overall size of the banks is important in assessing the vulnerability of particular companies to the virtual drying up of income from IPOS. Noting this, Odeon’s Dick Bove, a respected bank analyst, recently cut Goldman and Morgan Stanley to sell as reported here by SA News on September 6. Everybody knows that the number of IPOs is cyclical, but the real question in how long the cycle will be.

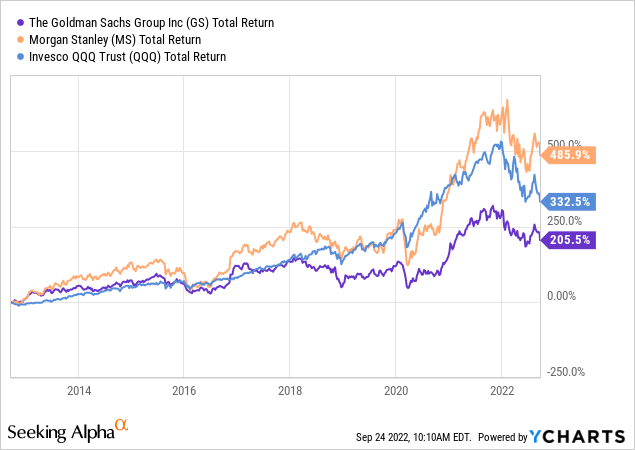

The question is not whether the investment banking giants are in temporary belt-tightening mode this quarter or next, or even next year, but whether there may be a longer term slow down. There’s no visible backlog of the kind of start ups which went public over the past three or four years. For over a decade underwriters benefited from a tailwind of innovative technology and business models. How will investment banking do if faced by a long cycle in which innovation is not the main theme? Here’s an interesting 10-year chart suggesting some correlation of investment banks and the tech heavy Invesco QQQ Trust (QQQ).

Seeking Alpha’s Quant Ratings give the two major investment banks very lukewarm Hold ratings. Goldman Sachs is dirt cheap at a 8.78 P/E ratio and after the recent drop sells at 1 times tangible book value. Ira heavy weighting in trading and underwriting/investment banking are the reasons it deserves to be cheap. Morgan Stanley has enjoyed superior long term performance and its strong brokerage and asset management units should support it while times are tough in investment banking. Its P/E of 12.24 makes it almost 40% more expensive than Goldman, however, and by far the most expensive of the six largest banks. Although it probably deserves that P/E, it is fully priced. Both GS and MS are tepid Holds.

Main Street Looks Like The Winner, But It’s Bye Bye Buybacks

Wells Fargo’s banking analyst Mike Mayo sees the same reversal of fortune that Dick Bove sees from the opposite side. Main Street banking has suffered for over a decade because low interest rates have meant poor Net Interest Income and poor Net Interest Margin (NIM). Mayo asserts, as SA News reported here, that it’s time for Main Street banking to take the lead. There are good arguments on his side. Main Street banks have generally done well in times of higher interest rates. First, though, they have to get themselves out of the Fed’s doghouse.

What happened to Bank of America and JPMorgan shouldn’t happen to a badly-behaved dog. They had been, in fact, well behaved, voluntarily cutting back their return of capital to shareholders at the beginning of the COVID lock down in 2020 and providing data-supported assurance that whatever happened in the economy they would be a part of the solution rather than a part of the problem. It should surprise no one that Jamie Dimon went ballistic about the constraints that came with the 2022 Fed Stress Tests. Not only did Bank of America and JPMorgan pass by the thinnest of margins but it gradually leaked that they had joined Citigroup, the chronically sick puppy of the mega cap banks, in being told privately that they needed to suspend buybacks until they had further improved their CET1 (Common Equity Tier 1) ratios. In layman’s terms, the Fed believed that they had too many risk assets (loans) for their equity capital.

JPM’s Jamie Dimon and BAC’s Brian Moynihan engaged this issue in different ways. In JPM’s Q2 earnings call, Dimon basically threw a public fit calling the tests “inconsistent… not transparent…too volatile… and basically capricious, arbitrary.” He noted how well the banks had performed in the pandemic when unemployment reached 15%, and he added that JPM would continue to write mortgages but sell them immediately and generally reduce holdings in risk assets in ways that would harm the US economy. This had no impact on the outcome, of course.

Brian Moynihan, on the other hand, actually filed an appeal seeking a reduction of its 3.4% Stress Capital Buffer on the grounds that the team doing the Stress Testing had not understood its Non-interest costs including “compensation” and “other”. You can read the August 4 response rejecting the appeal here. The Fed’s response: no dice, no buybacks. This may seem to be a minor point, but it is far from minor. When I first bought Bank of America in 2016 what attracted me was the prospect of large buybacks. For several years BAC met my expectations. From 2017 through 2021, excluding the pandemic year of 2020 when buybacks were halted, BAC had a shareholder return (dividends plus share buybacks) adding up to around 100% of earnings. Close to three quarters of that return was from buybacks.

While many investors think they prefer dividends, buybacks are by far the more powerful form of return. If nothing else, recipients can then sell the same percentage of their holdings for cash and still have the same percentage of ownership of the company as before. Meanwhile, they enjoy the tax benefit of receiving cash which may be at worst treated partially as long term cap gains. Most importantly, the company will see its per share earnings rise above what they would otherwise have been by the percentage of shares retired. The dividend can be increased in future years by the same percentage without more cash going out the door. When it comes to Bank of America these increases in per share performance were extremely important because aggregate revenues and earnings did not increase regularly or powerfully. Large buybacks were the main source of per share earnings growth.

That’s what the Fed took away when it took away buybacks “capriciously and arbitrarily” in the language of Jamie Dimon. Forget growth for a while, the Fed said. What made it worse was the timing. Most of the BAC buybacks in the last four years were done at prices much higher than the present, well over $40 per share, while the opportunity to buy back at substantially cheaper prices in 2020, and now in 2022, were halted by Fed mandate. If BAC can’t do buybacks before January 1, 2023, the new buyback tax will be in effect. That’s really doing a terrible thing to BAC shareholders.

Even Without Buybacks, There’s A Case For Diversified Banks

A few things are beginning to go well going the diversified banks with major consumer banking units, and the first is cost of funding. Bank of America greets rising rates with cost of funds at a dirt cheap level of $.09 followed closely by Wells Fargo at $.10. JPMorgan comes in at a decent $.22. Those are the minuscule amounts they most recently reported paying their depositors. BAC and WFC benefit greatly from branches and checking account balances. As BAC CEO Moynihan reported here in his presentation to the recent Barclays Global Financial Service Conference, about 56% of total Bank of America customer deposits are in checking accounts.

Those vost-of-funds numbers will climb, of course, with rising rates. I am already looking more closely at my own two accounts (one a Credit Union); I have been casual for over a decade about the money parked in those accounts but am likely to reduce the balance quite a bit as better options have materialized. I have heard others say the same. This will lift the cost of funds for BAC, WFC, and JPM. It is likely, however, that the rates paid to depositors will climb more slowly than the rising rates they can charge for loans. Thus both Net Interest Income and Net Interest Margin should improve.

Both JPMorgan and Bank of America have been solid performers in the long term under their present CEOs. JPM has maintained its position of leadership among US and Global Banks supported by its powerful presence in all major areas of banking and a balance sheet which truly merits the overused term “fortress.” Its management is deep and unsurpassed. Leadership of that sort provides a business and hiring advantage which comes from reputation, but it also imposes a conservatism which does not always maximize the ability to grow and increase shareholder return.

Buybacks have always been moderate at JPM, 2-3% (much lower than BAC’s sometime 7%) while its dividend growth has been steady but unspectacular. While it once traded at a premium accorded to quality its recent decline has brought its P/E down to 9.78, slightly lower than both BAC and WFC. Its dividend yield of 3.67%, granted, is about a point higher than theirs. In recent shareholder letters CEO Dimon has mentioned the importance of dividend income for its shareholders, perhaps explaining his apparent preference for dividends over buybacks. Over recent months JPM has underperformed its diversified bank peers, perhaps because quality has seemed less essential to performance as rates rise. Additionally, the fact that JPM has a proportionately larger business in the investment banking area may now be seen as a drag rather than a fortunate diversifier. I own a modest position in JPM which I will probably continue to keep. I therefore agree with the SA Quant Rating of Hold.

Bank of America Is Run By A Hyperactive Worker Bee

BAC CEO Brian Moynihan is likely to be Jamie Dimon’s successor as spokesman for the industry despite the fact that he apparently has a different temperament. He is focused on operational details to a fault and looks a lot less like the great merchant bankers of old, the Rothschilds, Fuggers, and Medici. While JPMorgan is run like an empire, Bank of America is run like a business, albeit a complicated one. Moynihan has done all the right things, pruning overly risky elements of the business. His focus has been on “responsible” growth as he reduced assets like credit cards (down 50%), home equity loans (down close to 80%), and construction/development (down 70%), thus positioning BAC to survive a major economic downturn.

Moynihan has also emphasized the importance of Bank of America employees, supporting them with liberal policies throughout the pandemic and being out front in elevating salaries (often better than having employees poached by rivals). He has emphasized equal opportunity and proper actions to support the environment. He has controlled costs while spending whatever is necessary to digitize bank operations and say ahead of fintech challengers. All of that is good, and may well pay off in the long run, but as a shareholder with a substantial position in BAC, I can’t help feeling that the detailed descriptions of management initiatives amount to a sort of cover for the current absence of good news for shareholders. Here’s how CEO Moynihan put it in the Q2 earnings call:

And thinking about capital, remember, first, we use our capital to support customers and related loans, and we continue to invest in the franchise. Second, we are delivering capital back to you, shareholders. We announced our intent to increase our dividend in quarter 3, which we have our dividend 22% higher than it was just 12 months ago. In addition, we retired shares this quarter. Third, we’re going to be building capital given the new higher amounts received during the stress test. It will make our balance sheet even stronger. Along the way, we believe our expected earnings generation over the next 18 months will provide an ample amount of capital, which allows us to support customer growth, pay dividends and use the rest to allocate between buying back shares and growing into our new capital requirement.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but that sort of buries the problem with the Stress Tests and the sadly lost opportunity with buybacks. For now I’m giving Brian Moynihan the benefit of the doubt, but in future I will be a lot less interested in the kind of details Wall Street analysts like to use when making their recommendations. My advice to Brian Moynihan is what I sometimes say to hyper kids to whom I teach tennis: how about taking a deep breath and swinging about 60% as hard. Less is more. In the next section I’ll talk about a bank which was forced to do this. What I want to hear in the next earnings call from Brian Moynihan is when Bank of America will return to focusing on the major actions that really benefit shareholders like me. Being hard to sell because of taxes I would pay on cap gains, I’m keeping Bank of America for now. It’s another somewhat reluctant Hold.

Is Wells Fargo Actually The Best Bet Among Big Banks?

For a couple of decades Wells Fargo was the “good bank” which treated its customers so well that it led the world in the “cross-selling” of products. The stickiness of its customers put other banks to shame. It survived the 2009 crisis with flying colors. It seemingly could do no wrong. Then the truth started to come out, scandal by scandal. The last straw was the “phony accounts” scandal which led the Fed in February of 2018 to impose an asset cap at #1.95 trillion in total assets. Wells Fargo was not allowed to expand its business until it cleaned itself up, a restraint which crippled both growth and profitability.

It also punished WFC shareholders. I know because I was one of them. I saw punishment coming and dumped my position in stages at prices which still make it a good sell. I then swore off Wells Fargo for what I thought was forever. Elizabeth Warren earned five minutes of my approval for calling for Wells Fargo’s dismissed and shamed CEO John Stumpf to have his salary and bonuses clawed back and be put up on criminal charges (neither of which happened, alas). Senator Warren’s demand made me briefly entertain the view that there was some good in everybody. Nah! On October 16, 2016, I wrote this article entitled “The Last Article You Will Ever See On Wells Fargo (At Least By Me). I lied. I didn’t foresee the outcome.

It would be a great story: CEO Charlie Scharf had come in, cleaned things up, gotten rid of the bad actors, and set WFC back on course to be the “good” Main Street bank. In truth WFC has actually done pretty well since 2018, and it’s hard to argue with Scharf’s results. In its turn at the September 13 Barclay’s Global Financial Service Conference WFC Chief Financial Officer Michael Santomassimo was able to affirm that its deposits were now 60-61% in its consumer business up from 40% a “couple of years” ago, making it likely that WFC least rate-sensitive bank when it came to cost of funds (edging out Bank of America’s 56%). Meanwhile, it was setting aside its ambition to be number 1 in the mortgage business just as the mortgage business began to go south. Net Interest Income had been up 11% for Q2 and and Net Interest Margin up23 basis points, with the same expected for the second half of the year, suggesting that its cost of funds was likely to remain low. Wells Fargo could just sit back with rising margins and be thankful that they have no exposure to capital markets. It was (fortunately) forced to hold down the level of loans because of the asset cap.

Did the new management team accomplish all that? Well, yes and no. The new management has done its job. The true story, however, is much better, more ironic, and funnier. What made Wells Fargo a big winner was the unintended consequences of the Fed’s asset cap. What does a bank do when it can’t raise its deposits above an established limit? They do the obvious thing, which is push away the less desirable deposits and hang on to the more desirable. In the present environment of high and rising rates, that means hanging on to “stickier” deposits which are likely to persist despite receiving lower rates. With their balance sheet frozen at $1.95 trillion they push away institutional money which will demand higher rates. What they are left with is gushing cash flow from the higher Net Interest margin – the difference between higher loan rates and the pittance paid out in checking accounts. This outcome was predicted in this Wall Street Journal April 23, 2021, “Heard on the Street” column as reported the same day in SA News by Liz Kriesche. Both pieces make for very interesting reading.

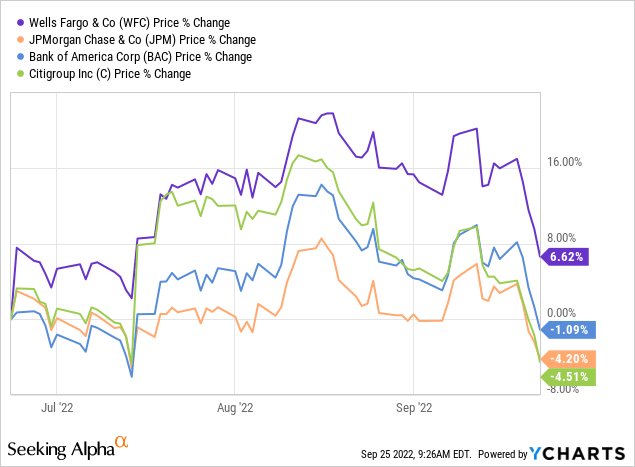

There are several takeaways here. Number two is that Elizabeth Warren was once right for about five minutes. She promptly returned to being wrong and uninformed, I must add, by suggesting the break-up of Wells Fargo. What’s to break up? It’s pretty much just a community bank with branches elevated to power N. Number two is that the Fed can’t get anything right, not even a simple punishment of a misbehaving bank. Number three is that both Brian Moynihan and Jamie Dimon should have a look at what went right (accidentally) at Wells Fargo. Number four is that with the help of the Fed’s asset cap WFC passed the Stress Tests with flying colors. Since the asset cap was imposed has done buybacks at a rate BAC and JPM shareholders can only dream of. What else could it do with cash? Doing well on the Stress Tests give it the ability to continue to do so. Here’s a chart of the four major Main Street banks since the release of the stress tests:

That’s Wells Fargo leading the three banks damaged by poor performance on the stress tests which derived from overreach in risks assets. I thought I would never say this, but WFC is the big winner among the six mega-cap banks. SA’s Quant Ratings somehow sussed this out and make WFC a Strong Buy as against a lukewarm hold for the other five banks. I couldn’t agree more, If I were thinking of buying anything in the financial area at the present moment (I am not) it would be Wells Fargo.

What Are The Risks?

Wells Fargo has clear edge among the major banks but all six participate to some degree in the same risks. Here are a few:

- All major banks with any participation in capital markets face the possibility that the downturn in underwriting is part of a longer than usual cycle.

- All banks face the risks that the Fed will overshoot in its war on inflation. An increasing number of deep thinkers like Jeffrey Gundlach and Mohamed El-Erian think the Fed will overdo tightening to a degree that results in a calamitous recession. Jeremy Siegel joined that camp in the past couple of weeks. I woke up yesterday thinking that it would amount to what the Fed did in 1929, raising rates into what proved to a recession already underway with strong indicators such as declining rail car loadings. You can read about it John Kenneth Galbraith’s wonderful and readable book The Great Crash: 1929 which I have reread four or five times since I was a teenager.

- What if inflation and interest rates make a round trip? That could be the result if the Fed prevails with a minor recession. Where does that leave banks if inflation and interest rates fall to 2-3%? The most likely answer is that they return to the miserable conditions which persisted through the 2010s with low NII and NIM, forced to somehow generate earnings with fees.

- A depositor revolt could force banks to pay more even in checking accounts producing a big disappointment in margins. Or the demand for loans could fall as rates increase.

- A major Democrat win in the mid-term elections could enable Elizabeth Warren to inflict unimaginable things on the big banks, effectively pushing them into utility status which looks a bit like nationalization.

You can fit your own sense of the probabilities onto the above risks. The default case, as in all things, is that we will muddle through and so will the banks. You feel better believing that on a day to day basis, and that’s how most of us live our lives. If you feel you need to buy a bank, Wells Fargo is the one. Just don’t overestimate how well you will do with financials just because they look cheap on current numbers.

Be the first to comment