Jason Doiy/iStock Unreleased via Getty Images

It’s been about 30 months since I put out my bullish article on Macy’s Inc. (NYSE:M), and in that time, the shares have returned about 85% against a gain of about 50% for the S&P 500. Now, I want to revisit this trade for a few reasons. First, and most importantly, doing so allows me to indulge in one of my favourite pastimes: bragging. This particularly odious trait has lost me a few friends over the years, but it’s just too much fun. While I try to ignore that pesky little voice in my head that’s yammering some nonsense about “pride goeth before destruction”, I’ll list some of the other reasons to write about Macy’s again. A capital gain is great, but a stock trading at $26.25 is, by definition, more risky an investment than when that same stock was trading at $15.50. I need to work out for myself whether or not I should hold this name. I’ll make that determination by looking at the financial history since I bought, and at the stock as a thing distinct from the underlying company. Also, I recommended a short put trade, and you gotta know that I’ll be bragging about that, too, while recommending yet another short put. Finally, I’m going to present to you readers a way that I’m starting to think about stocks in light of rising interest rates. The message over the years has been incessant. Dividend paying stocks are compelling because the return you get on risk reduced government debt is so paltry. That may have made sense in a very low rate world. In this article I want to examine that old saw more closely by comparing treasury notes to Macy’s stock.

Welcome to the “thesis statement” portion of the article, dear readers. I offer this to people because I know that my writing can be, uh, “a bit much.” For people who have lower than average immunity to my horrible jokes, I present the “gist” of my argument here, just in case they missed the title and three bullet points above. In spite of the run up in price, I still think Macy’s is a screaming buy, so I’ll be buying more at current prices. I think the dividend is exceptionally well covered, and the stock is trading at an objectively cheap price. In addition, I’ll be enhancing the cash return, and thus closing the gap on treasury notes, by selling the November puts with a strike of $18 for ~$1.30. There you have it. That’s the gist of my argument. So, if you read on, any nausea or trauma you feel as a result is entirely on you. I don’t want to read anyone moaning in the comments section about the terrible bragging, or anything about how I pronounce or spell words the proper, non-American way.

Financial Snapshot

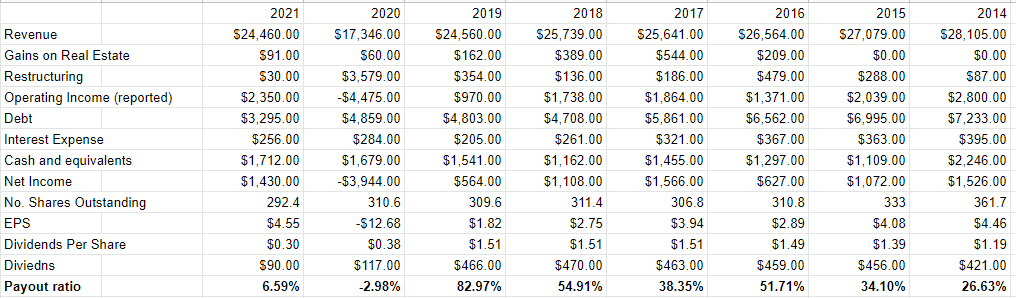

It seems that in the year 2021, the company returned to something like “normal.” In particular, revenue was up nearly 41% from the year of the pandemic, but was basically flat (down .41%) relative to 2019. At the same time, though, it could be argued that the company emerged from the year of the pandemic much improved. For instance, profitability in 2021 was fully $866 million (or 153%) higher. At the same time, debt declined by about $1.5 billion from 2019 to 2021. All in, I’d suggest that the income statement is in the best shape it’s been in since at least 2017, and let’s not forget that FY 2017 had 53 weeks. The capital structure has never been this strong in my estimation. This performance has been great, but we live in a world of choices, and I think much of this stock price is a function of the sustainability of the dividend, so I want to go into depth about these two issues.

The “Everything in Investing is Relative” Tool

For the last little while I’ve been thinking about the effects of current treasury yields on stocks. In particular, I’m trying to answer the question: “in a world where an investor can receive a yield of 2.88% from U.S. government debt, how should investors think about the current dividend yields on stocks?” After all, for the past several years I’ve heard from bullish investors describe why stocks are such great investments because the yield on government debt is so paltry. If that argument ever held merit, then, by definition, stocks would be less attractive investments in a world of higher interest rates.

This is obviously a very complex question, with many variables, but I think a helpful first step in deciding what we’d be willing to pay for stocks would be to look at the cash flows between a 10-year Treasury note and a given stock. The stock may get a valuation “bonus” from potential growth, but I think it’s worthwhile working out how much of the current price is a function of that growth, and how much is a function of the cash investors can pocket.

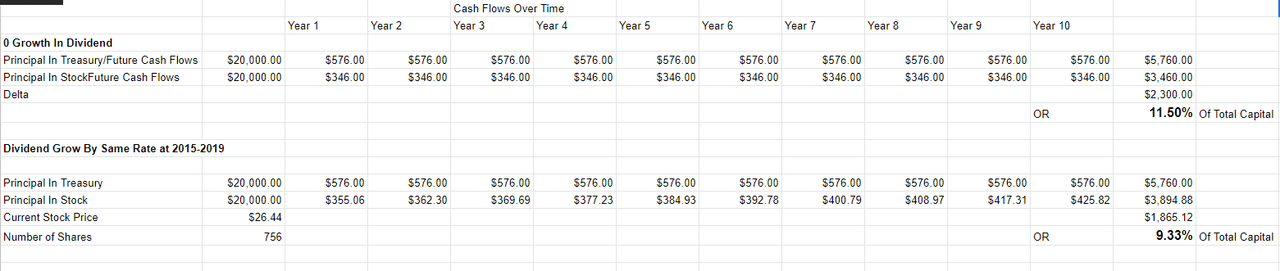

In aid of answering the first part of this question, I’ve created a simple spreadsheet that tries to start to tackle this question. It compares the cash flows from both the treasury and the stock over a 10 year period. It also compares the constant cash flows from the treasury to growing dividends on the other. I assume the dividend will grow at the same rate for the next decade as it did for the period 2015-2019. This is obviously a very simple assumption, and won’t be perfect, obviously, but I think it will help offer some insight into the relative investment merits of each asset.

I’ve applied this tool to Macy’s with the following starting rules, and have found the following:

-

The investor can invest $20,000 in either the treasury or they can invest that $20,000 to buy exactly 756 shares of Macy’s.

-

In the scenario where Macy’s does not raise its dividend over the next decade, the treasury investor finishes with an extra $2,300 in cash flows, or an extra 11.5% of the original investment.

-

In the scenario where Macy’s raises its dividend at the same rate as it did between 2015-2019 (i.e. at a CAGR of 2.04%), the treasury investor finishes with an extra $1.856.12 or 9.33% of the original investment.

In my view, this analysis suggests that for an investor to be indifferent between Macy’s stock, and a 10-year U.S. Treasury note, they’d need to assume two things. First, that the company will grow its dividend over the next decade at the rate that it did over the period 2015-2019. Second, that the shares will appreciate by ~9.5% from now to 2032. Alternatively, if the company does not raise the dividend, it’ll need to appreciate by 11.5% between now and 2032.

This tool doesn’t answer the question “stocks or bonds” definitively, obviously. It doesn’t talk about the risks associated with each investment, and there are obvious, and large, differences between the risks of the stock versus the U.S. government. That said, I think it’s a worthwhile first step. It helps quantify the relative merits of each, which goes a long way to answering the question in my view.

Finally, there is a very important caveat to consider when reviewing the relative performance here. As you can tell by the fact that I spell words like “favour” and “characterise” properly, I’m not an American. One of the many implications of this is that I’m taxed at the same (near criminal) rates whether I receive cash from Uncle Sam or from the dividend of a U.S. corporation. If you’re an American, you’ll want to apply an after tax version of this model, applying the tax shield for the dividend for instance. Alternatively, you’ll need to make the comparison in the context of a tax sheltered account like the (very strangely named) “IRA”, for instance.

Treasury v Dividend Cash Flows (Author calculations, public data sources)

Dividend Sustainability

Now that I’ve expressed the importance of the dividend in my thinking, it’s time to look at the extent to which said dividend is sustainable. As my regular readers know, I do this by looking at the size and timing of future obligations, and comparing those to the current and likely future sources of net cash.

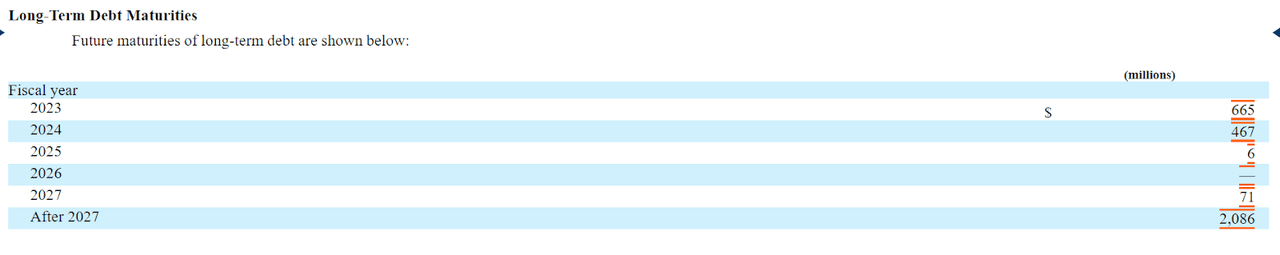

We see from the tables below, taken from pp F-24 and F-19 respectively from the latest 10-K for your reading pleasure, the company has to repay $665 million in 2023, and another $467 million 2024, after which the repayment schedule is fairly light until 2027.

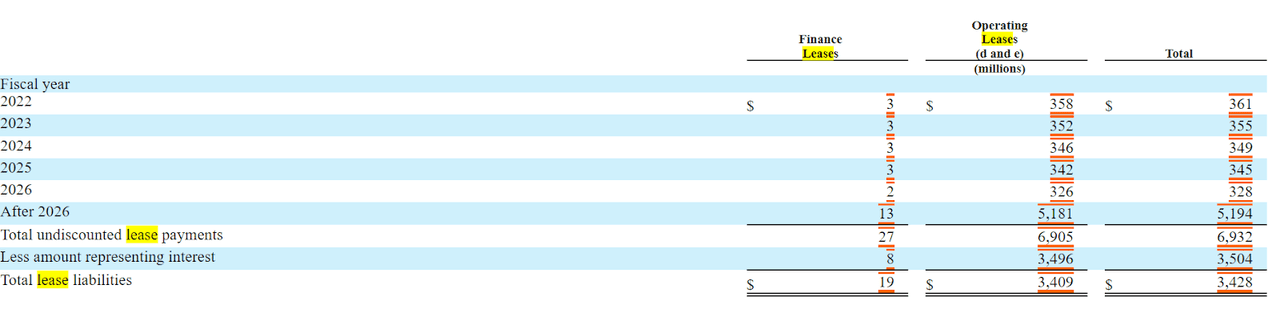

Add to these the lease obligations ranging between $345 and $361 million in each of the next several years, per the table below, and we see that the company is on the hook for $366 million this year, $1.026 billion next year, and $816 million in 2024.

Macy’s debt schedule (Macy’s 2021 10-K)

Macy’s lease schedule (Macy’s 2021 10-K)

Against these obligations, the company currently has ~$1.7 billion in cash. Additionally, they’ve generated an average of about $1.656 billion in cash from operations over the past three years. Over the same period, they’ve spent an average of $565 million in CFI activities on the firm.

All of the above suggests to me that the dividend is well covered, and that we may see growth from current levels. For this reason, I’d be very happy to buy the stock at the right price.

Macy’s Financials (Macy’s Investor relations)

The Stock

Some of you who follow me regularly for some reason know that this is the point in the article when I turn into a real “downer.” It’s here where I start writing about risk-adjusted returns, and how even the stock of a sustainable dividend machine can be a terrible investment at the wrong price. A company can make a great deal of money, but the investment can still be a terrible one if the shares are too richly priced. This is because all businesses are essentially just organisations that take a bunch of inputs, add value to those inputs, and then sell products or services (hopefully) for a profit. The stock, on the other hand, is a proxy whose changing prices reflect more about the mood of the crowd than anything to do with the business. In my view, stock price changes are much more about the expectations about a company’s future. This is why I look at stocks as things apart from the underlying business.

If you hoped that I’d make this point and move on, well get ready for a large helping of disappointment, because I’m not quite done. I feel a need to demonstrate the importance of looking at the stock as a thing distinct from the business by using Macy’s stock itself as an example. The company released annual results on March 25th. If you bought this stock that day, you’re up about 1.9% since then. If you waited until April 7th, you’re up a staggering 18.8% since. Not enough changed at the firm over this short span of time to warrant a 20%+ variance in returns. The differences in return came down entirely to the price paid. The investors who bought virtually identical shares more cheaply did better than those who bought the shares at a higher price. This is why I try to avoid overpaying for stocks.

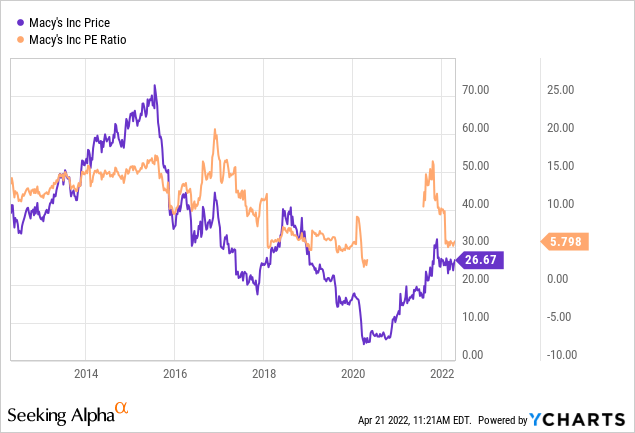

My regulars know that I measure the cheapness (or not) of a stock in a few ways, ranging from the simple to the more complex. On the simple side, I look at the ratio of price to some measure of economic value like sales, earnings, free cash flow, and the like. Ideally, I want to see a stock trading at a discount to both its own history and the overall market. In my previous missive on this name, I got downright giddy at the prospect of buying this company at a PE just below 5. It’s higher now, but is still objectively cheap in my view, per the following:

Source: YCharts

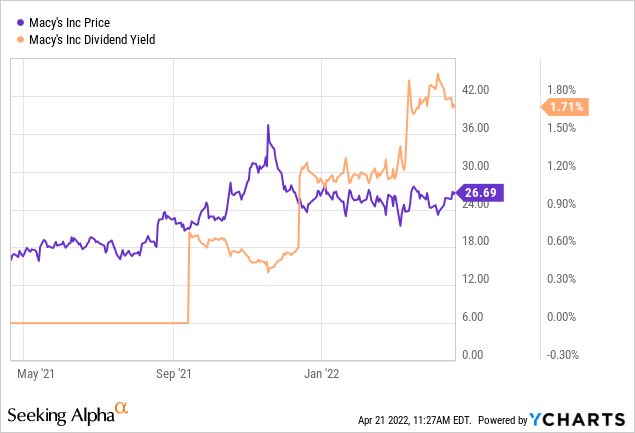

At the same time the shares are relatively cheaply priced, investors are collecting higher dividend yields, per the following:

Source: YCharts

In addition to simple ratios, I want to try to understand what the market is currently “assuming” about the future of this company. If you read me regularly, you know that I rely on the work of Professor Stephen Penman and his book “Accounting for Value” for this. In this book, Penman walks investors through how they can apply the magic of high school algebra to a standard finance formula in order to work out what the market is “thinking” about a given company’s future growth. This involves isolating the “g” (growth) variable in a fairly standard finance formula. Applying this approach to Macy’s at the moment suggests the market is assuming that this company will be bankrupt within nine years, which is wonderfully pessimistic in my estimation, and for that reason, I’m willing to buy some more shares.

Options Update and Recommendation

In my previous missive on this name, I recommended selling May 2020 puts with a strike of $14 for $2 each. You may remember that the first few months of 2020 were actually quite bad for stocks, and as a consequence, these shares were “put” to me at a net price of ~$12. The trade worked out very well in the end, but it was stressful at the time. I’ve written that selling puts enhances returns and reduces risk, but I never promised that they’d accomplish this in an emotionally comfortable way.

I like to try to repeat success when I can, so I’m going to be selling some more puts today. I consider these to be “win-win” because I’ll do well if the shares remain above the strike price, or if the shares fall in below the strike price. At the moment, my preferred trade is the November short put with a strike of $18. These are currently bid at $1.30. So, if the shares don’t happen to drop 32% over the next seven months, I’ll pocket this 7.2% yield. If the shares fall below $18, I’ll be obliged to buy, but will do so at a net price of $16.70. Holding all else constant, this price lines up with a dividend yield of 2.7%, and a PE of 3.63. This is also a very positive outcome in my view. This is why I characterise these as “win-win” trades.

It’s that time again. Welcome to the point in the article where I get to indulge in my semi-sadistic tendency to spoil people’s moods by pointing out that the phrase “win-win” is really just a bit of rhetoric. This trade, like all others, comes with risk. I consider the risks associated with these instruments to fall into two broad categories: the economic and the emotional.

Starting with the economic risks, I’d say that the short puts I advocate are a small subset of the total number of put options out there. I’m only ever willing to sell puts on companies I’d be willing to buy, and at prices I’d be willing to pay. So, I would never advocate that people simply sell puts with the highest premia. In my view, that strategy would lead to disastrous results. So, dear reader, only ever sell puts on companies you want to own at (strike) prices you’d be willing to pay.

The two other risks associated with my short puts strategy are both emotional in nature. The first involves the emotional pain some people feel from missing out on upside. To use this trade as an example, let’s assume that the stock price of Macy’s shoots to $50 per share between now and the third Friday of November 2022. Obviously my puts will expire worthless, which is a great outcome in some ways. I will not catch any of the upside in the stock price, though. So, short put returns are capped by the premium received. This is emotionally painful for some more hopeful souls. Thankfully for me, my expectations have been lowered dramatically over the decades, so this isn’t really an emotional hardship for me. Also, I’m long the stock and will be adding more shares today, so this, too ameliorates any pain from puts missing upside.

Secondly, it can be emotionally painful when the shares crash below your strike price. As I wrote above, this happened to me in 2020 in this case. Buying Macy’s at a net price of $12 worked out, as every one of my trades that have been “put” to me has, because the strike prices I sell at are “screaming buys.” The fact that things work out well in the end doesn’t mean it’s not emotionally painful, though. I think people who sell puts should be aware of these emotional risks before selling.

If you understand these risks, and can tolerate them, I would recommend that you sell puts, as well as buy shares. I think short puts enhance the risk adjusted return fairly massively here, and so we should sell them.

Conclusion

I think Macy’s has had a wonderful time of it lately, and I think the shares are trading at objectively cheap prices in spite of this. For that reason, I’m comfortable buying some shares, and selling the puts described above. The income received may (or may not) be as great as that received from a treasury note, but if you add the put premium, you get quite close. Given the current strength of the dividend, I think it’s reasonable to suggest that we may get faster than usual growth in the dividend. If you’re comfortable selling puts, I’d recommend you sell puts and by shares. If you’re not comfortable selling puts, I’d recommend you buy shares.

Be the first to comment