Smederevac

Introduction

When I started playing Monopoly, I soon realized how powerful railroads were. I then found out the Days of Wonder board game called Ticket to Ride, where I usually play with the North American map. Here I learned how vital certain railroad tracks are compared to others. For sure, these two aspects made me think for some time about railroad companies. These have caught my attention in the past months for two main reasons: the recent supply chain bottlenecks that seem to be easing up and the entry barriers that prevent new companies from being formed and increase competition. These two aspects made me curious about this industry to the point that I have started researching it in order to see whether or not to invest in one or more stocks. As I was figuring out how to compare the different companies, I realized that I could learn this from none other than Warren Buffett himself. In fact, Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A, BRK.B) owns one of the largest North American Class 1 railroads: Burlington Northern Santa Fe. Since Berkshire’s completed the acquisition of BNSF in 2009, Buffet has spent a lot of words in his shareholder letters and in the annual reports to help everybody understand how he thinks about this investment and how he is able to give a fair valuation of the business. In this article I would like to share the key points of Buffett’s thinking about this investment in order to jot down a few criteria to use as I plan on publishing a series of articles on the major class 1 railroad companies in North America: Canadian National Railway (CNI), Canadian Pacific Railway (CP), CSX Corporation (CSX) , Norfolk Southern Corporation (NSC), Union Pacific Corporation (UNP).

The Mind Frame

Before we dive into the railroad investment, we have to spend a few words on what many already know about Buffett and Munger’s mind frame when investing. In their most recent shareholder letter they stated clearly that the

goal is to have meaningful investments in businesses with both durable economic advantages and a first-class CEO. Please note particularly that we own stocks based upon our expectations about their long-term business performance and not because we view them as vehicles for timely market moves. That point is crucial: Charlie and I are not stock-pickers; we are business-pickers.

From this we can extract the first step: BNSF is a business Buffett and Munger wanted to own.

More than twenty years ago, Buffett and Munger had already made clear that, though they may look at common metrics, the real key to understanding the value of a business is the discounted vale of the future cash flows. These are their words taken from the 2000 Berkshire shareholder letter:

Common yardsticks such as dividend yield, the ratio of price to earnings or to book value, and even growth rates have nothing to do with valuation except to the extent they provide clues to the amount and timing of cash flows into and from the business. Indeed, growth can destroy value if it requires cash inputs in the early years of a project or enterprise that exceed the discounted value of the cash that those assets will generate in later years. Market commentators and investment managers who glibly refer to “growth” and “value” styles as contrasting approaches to investment are displaying their ignorance, not their sophistication. Growth is simply a component usually a plus, sometimes a minus in the value equation. […] But value is destroyed, not created, by any business that loses money over its lifetime, no matter how high its interim valuation may get.

I think these words are pretty clear. No stock metric makes sense if it is decoupled from the most important part: the underlying business needs to have a life ahead of cash inflows that will make it earn money. Here is the second takeaway: Buffett and Munger saw BNSF future cash flows as promising and long-lasting.

Thirdly, I think these other words it will be very important in order to approach railroads as they tackle a problem that we will have to consider thoroughly: capital expenditures, which are massive for railroads:

When Charlie and I read reports, we have no interest in pictures of personnel, plants or products. References to EBITDA make us shudder, does management think the tooth fairy pays for capital expenditures? We’re very suspicious of accounting methodology that is vague or unclear, since too often that means management wishes to hide something. And we don’t want to read messages that a public relations department or consultant has turned out. Instead, we expect a company’s CEO to explain in his or her own words what’s happening.

I think these words destructure a common way of thinking that sees EBITDA as one of the most important metrics. Of course, it does provide a picture of the ability of a company to make profits. However, no company is disembodied from society, where interest, taxes and capex do exist and do have an impact on real profits. Third takeaway: Buffett and Munger are well aware of the impact of capex for a company.

BNSF Purchase

Berkshire initiated its position in BNSF in 2007, but at that point, Buffett didn’t talk a lot about this purchase, apart from a brief answer during the 2007 shareholder meeting. When asked about railroads, he replied in this way:

It will never be a sensational business. It’s a very capital-intensive business. And when you put tons of capital out every year, it’s very hard to earn really extraordinary returns on capital.

But if they earn a decent return on capital, it can be a good business over time, and it can be a lot better business than it was in the past.

We see right from the start the capex issue. However, Buffett highlights two factors: capex is not itself a hinderance if the business is able to have a decent return on capital because, over time, the returns can compound. Secondly, the business environment for railroads was already in improving around 2007.

In 2009 Buffett decided to take hold of the entire company offering $26 billion to buy the77.4% of the company he still didn’t own. To know the full story of how Buffett crossed his road with this railroad, it could be interesting to read pages 9 to 11 of the 2021 shareholder letter.

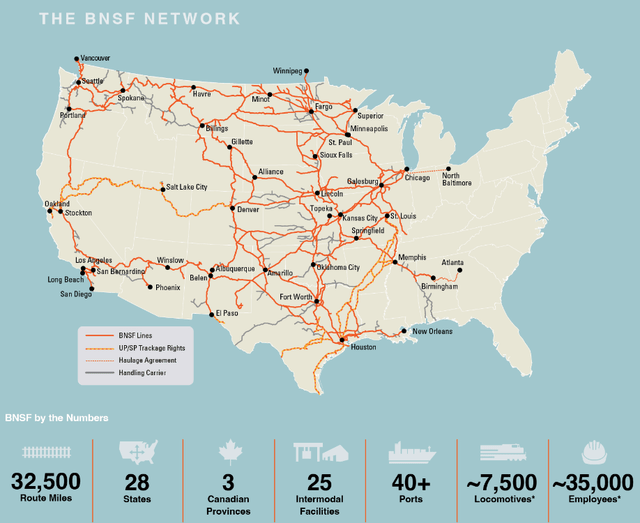

Let’s fast forward to 2010, when the deal between Berkshire and BNSF had already been signed and Buffett could proudly say that his company owned this massive railroad that is the product of almost 400 different railroad lines M&As over 170 years. The current rail network has 32,500 route miles in 28 states and three Canadian provinces, as we can see from the map below.

In the 2010 shareholder letter Warren Buffett spent quite a few words to inform Berkshire’s shareholders about the recent acquisition, called the “highlight of 2010”:

Both of us are enthusiastic about BNSF’s future because railroads have major cost and environmental advantages over trucking, their main competitor. Last year BNSF moved each ton of freight it carried a record 500 miles on a single gallon of diesel fuel. That’s three times more fuel-efficient than trucking is, which means our railroad owns an important advantage in operating costs. Concurrently, our country gains because of reduced greenhouse emissions and a much smaller need for imported oil. When traffic travels by rail, society benefits. Over time, the movement of goods in the United States will increase, and BNSF should get its full share of the gain. The railroad will need to invest massively to bring about this growth, but no one is better situated than Berkshire to supply the funds required. However slow the economy, or chaotic the markets, our checks will clear.

The first thing Buffett highlighted is the future forecast. This agrees with what we have seen above: the general mind frame must be forward-looking. It is important to note that the forecast is not just an optimistic view about the future, but that it is anchored on facts that Buffett highlights:

- cost and environmental advantages over trucking

- fuel efficiency that lead to better operating costs

- increasing need for freight trains

These facts build up what we have learned to call moat or competitive advantage, an aspect Warren Buffett always looks at when buying a business. Buffett also addresses the need that railroads will have for massive investments in order to support their requested growth. Here Berkshire is the ideal parent company as it has billions to deploy (the most of which come from what Buffett calls “float”, a key concept to understand Berkshire Hathaway’s business model) whenever it finds an interesting way of investing them. Let’s see what Buffett writes about the huge investments BNSF needs. In the shareholder letter he talks about the railroad and MidAmerican Energy since they have common characteristics:

A key characteristic of both companies the huge investment they have in very long-lived, regulated assets, with these funded by large amounts of long-term debt that is not guaranteed by Berkshire. Our credit is not needed: Both businesses have earning power that, even under very adverse business conditions, amply covers their interest requirements. For example, in recessionary 2010 with BNSF’s car loadings far off peak levels, the company’s interest coverage was 6:1.

Though Berkshire Hathaway has plenty of cash and can thus fund any kind of investment BNSF needs, Buffett chose a company that can stand on its own and that has enough earning power to cover its interest requirements. I think this should be highlighted very carefully: too often investors choose unprofitable stocks in order to bet on market swings. Buffett doesn’t move like this, he wants to own businesses that are healthy and profitable. It seems banal, but we have seen many times that it is not so for many investors.

Railroads have another problem: they are a regulated business. Buffett is aware of this limit and this is how he views it:

Both companies are heavily regulated, and both will have a never-ending need to make major investments in plant and equipment. Both also need to provide efficient, customer-satisfying service to earn the respect of their communities and regulators. In return, both need to be assured that they will be allowed to earn reasonable earnings on future capital investments. […] We are a major and essential part of the American economy’s circulatory system, obliged to constantly maintain and improve our 23,000 miles of track along with its ancillary bridges, tunnels, engines and cars. In carrying out this job, we must anticipate society’s needs, not merely react to them. Fulfilling our societal obligation, we will regularly spend far more than our depreciation, with this excess amounting to $2 billion in 2011. I’m confident we will earn appropriate returns on our huge incremental investments. Wise regulation and wise investment are two sides of the same coin.

I think these words show how deeply trusts America as one of the most friendly environments to see business thrive. He relies on the fact that the regulators will recognize the significant amount of investments and the satisfying services the railroad offers by allowing BNSF to earn a reasonable amount that will make it willing to continue running this business. In other words, he believes it is reasonable to have trust in the relationship with the regulators, that is, he believes BNSF is a business that lives in a favorable environment.

But why did Buffett pick BNSF and not another railroad? From a certain point of view, Buffett knows that it simply happened that he came across this railroad. But, being a keen investors, he points out that, in addition to the competitive advantages we saw above, BNSF enjoys one favorable tailwind: American population is shifting to the West (the old motto “from sea to shining sea” is still moving America). To be fair, population is actually shifting to the South, too. But both regions are well-served by BNSF as we have seen in the map above. Buffett highlighted this trend in his 2010 letter:

Rail moves 42% of America’s inter-city freight, measured by ton-miles, and BNSF moves more than any other railroad – about 28% of the industry total. A little math will tell you that more than 11% of all inter-city ton-miles of freight in the U.S. is transported by BNSF. Given the shift of population to the West, our share may well inch higher.

From this paragraph I gather another aspect to look at. The geography of the railroad has to be looked at through the lens of demographics. In other words, geography is important based on the demographics it connects. Since the current trend is an expansion of the West and the South, the increasing population in these areas is per se a driver of freight growth.

The issue of capital-intensive businesses

Let’s elaborate a bit more on capex required by a railroad. Again, let’s start from Buffett’s experience as it is told in the 2009 shareholder letter

In earlier days, Charlie and I shunned capital-intensive businesses such as public utilities. Indeed, the best businesses by far for owners continue to be those that have high returns on capital and that require little incremental investment to grow. We are fortunate to own a number of such businesses, and we would love to buy more. Anticipating, however, that Berkshire will generate ever-increasing amounts of cash, we are today quite willing to enter businesses that regularly require large capital expenditures. We expect only that these businesses have reasonable expectations of earning decent returns on the incremental sums they invest. If our expectations are met – and we believe that they will be – Berkshire’s ever-growing collection of good to great businesses should produce above-average, though certainly not spectacular, returns in the decades ahead.

Here we have an important takeaway: investing in railroads or utilities may also depend on the amount of cash an investor has. Buffett and Munger here hint that investors who have small amounts of cash could have better chances of finding businesses that require little incremental investment to grow and that could offer higher returns. As the size of a portfolio increases and it becomes massive, then it becomes more and more difficult to gain very high results, that is, it is more and more difficult to find only great businesses. However, though great businesses are few, there are quite a bit of good businesses. Buffett lets us understand that he thinks BNSF is a good business, with certain competitive advantages, a healthy balance sheet and the ability to produce above average returns for a long period of time. Personally, this is one of the aspects that is making me ponder thoroughly whether I want to be invested in railroads now, given the small size of my portfolio and my age. This is why I want to research the industry thoroughly to then come up with a conclusion of my own.

Secondly, capex needs to generate a decent return. However, part of this return depends, as we have seen, on regulators. This means that there is a risk in this industry that we don’t find in other areas. In fact, regulators may change the amount of allowable returns. However, they can’t do this arbitrarily because it is in the nation’s interest to have well-run and well-maintained infrastructures. This is how Buffett sees the problem, with words, they may seem repeated but that actually clarify the strong almost unbreakable bond between a railroad and the regulators:

Our BNSF operation, it should be noted, has certain important economic characteristics that resemble those of our electric utilities. In both cases we provide fundamental services that are, and will remain, essential to the economic well-being of our customers, the communities we serve, and indeed the nation. Both will require heavy investment that greatly exceeds depreciation allowances for decades to come. Both must also plan far ahead to satisfy demand that is expected to outstrip the needs of the past. Finally, both require wise regulators who will provide certainty about allowable returns so that we can confidently make the huge investments required to maintain, replace and expand the plant. We see a “social compact” existing between the public and our railroad business, just as is the case with our utilities. If either side shirks its obligations, both sides will inevitably suffer. Therefore, both parties to the compact should – and we believe will – understand the benefit of behaving in a way that encourages good behavior by the other. It is inconceivable that our country will realize anything close to its full economic potential without its possessing first-class electricity and railroad systems.

The last words are clear: railroads (and utilities) are a must-have for a country that wants to unleash its whole economic potential.

One last note, Buffett’s purchase of BNSF happened during one of the darkest economic periods: the Great Recession. To some extent, this year’s market seems to be anticipating a recession for 2023. Here is how the Oracle of Omaha saw that period:

We’ve put a lot of money to work during the chaos of the last two years. It’s been an ideal period for investors: A climate of fear is their best friend. Those who invest only when commentators are upbeat end up paying a heavy price for meaningless reassurance. In the end, what counts in investing is what you pay for a business – through the purchase of a small piece of it in the stock market – and what that business earns in the succeeding decade or two.

Once again, he pointed out at a long-term horizon as the correct time frame to measure the success of a business. He is so confident in this business that he actually stated in his recent shareholder letter the following prediction: “I’ll venture a rare prediction: BNSF will be a key asset for Berkshire and our country a century from now”.

What to look for in a railroad

Earning power

We can now move one more step in this research. How does Buffett see if the railroad is well-managed and it can deliver good returns over time? In the 2011 Shareholder letter he explained the most important point: the earning power. In order to be strong, this power needs to cover amply all the interest requirements a company has even under terrible circumstances. In fact, he explained that BNSF has

earning power that even under terrible business conditions amply covers their interest requirements. In a less than robust economy during 2011, for example, BNSF’s interest coverage was 9.5x. […] Two key factors ensure its ability to service debt under all circumstances: the stability of earnings that is inherent in our exclusively offering an essential service and a diversity of earnings streams, which shield it from the actions of any single regulatory body. Measured by ton-miles, rail moves 42% of America’s inter-city freight, and BNSF moves more than any other railroad – about 37% of the industry total. A little math will tell you that about 15% of all inter-city ton-miles of freight in the U.S. is transported by BNSF. It is no exaggeration to characterize railroads as the circulatory system of our economy. Your railroad is the largest artery.

Interest coverage

How is the earning power built? First of all, interests need to be well-covered. Secondly, the business must be in a key position within a country’s economy, as BNSF is. Thus, investors will always have to look at how a railroad is managed to assess if the interest expense is covered or not. As explained in the 2011 Annual report:

This “what-will-they-do-with-the-money” factor must always be evaluated along with the “what-do-we-have-now” calculation in order for us, or anybody, to arrive at a sensible estimate of a company’s intrinsic value. That’s because an outside investor stands by helplessly as management reinvests his share of the company’s earnings.

If there is no certainty that the management will use the railroad money to take care of this crucial point, then investors should stay away from the stock. Hence, it becomes even more important to understand the quality of the management.

Regarding interest coverage, what can we learn from Buffett in order to handle this concept? In the 2012 Shareholder letter, he writes that

BNSF’s interest coverage was 9.6x. Our definition of coverage is pre-tax earnings/interest, not EBITDA/interest, a commonly-used measure we view as deeply flawed.

Once again, we see that he doesn’t like EBITDA a lot, since he prefers pre-tax earnings (EBT).

Fuel-efficiency

Buffett has pointed out several times that BNSF is able to carry a ton of freight about 500 miles on a single gallon of diesel fuel which is just a quarter of the fuel a truck would use for the same job. I think this goes along with other operating metrics that need to show how a railroad becomes more and more efficiently as billions of investments are poured in.

Use of capital instead of paying dividends

Finally, though Buffett enjoys receiving dividends from his companies, he is not focused on them. Actually, he is not as fond of dividends as of other aspects of a company. This is because he accepts dividends only when the company has excess cash that it can’t invest at a reasonable rate of return. He states this concept talking about Berkshire and its ownership of BNSF:

BNSF is a case in point: It is now worth considerably more than our carrying value. Had we instead allocated the funds required for this purchase to dividends or repurchases, you and I would have been worse off.

This means that we can look at railroads for their dividend, but we have to keep in mind that this is a consequence of a well-run business with excess cash and it should not become what drives a person to invest in any of the stocks we will analyze.

Results Buffet has achieved so far with BNSF

How has Buffett’s investment turning out to be? Well, when Berkshire purchased the company in 2009, the railroad was doing $1.7 billion in net earnings. Let’s hear from Buffett’s words the latest results:

BNSF, our third Giant, continues to be the number one artery of American commerce, which makes it an indispensable asset for America as well as for Berkshire. If the many essential products BNSF carries were instead hauled by truck, America’s carbon emissions would soar. Your railroad had record earnings of $6 billion in 2021. Here, it should be noted, we are talking about the old-fashioned sort of earnings that we favor: a figure calculated after interest, taxes, depreciation, amortization and all forms of compensation. (Our definition suggests a warning: Deceptive “adjustments” to earnings – to use a polite description – have become both more frequent and more fanciful as stocks have risen. Speaking less politely, I would say that bull markets breed bloviated bull . . ..) BNSF trains traveled 143 million miles last year and carried 535 million tons of cargo. Both accomplishments far exceed those of any other American carrier. You can be proud of your railroad.

So, it is pretty clear that BNSF has thrived and so has Berkshire. In just 12 years BNSF has been able to invest a lot of capital while boosting its earnings up by almost four-fold.

Conclusion

In this article I wanted to trace a case study that will help me go across the publicly traded railroads in order to assess them fairly. Of course, I will use also regular metrics, but I will consider thoroughly the following key points: demographics of geography, purpose of capex, return on capital employed, net earnings and dividend policy.

A note for experienced railroad investors: feel free to leave a comment sharing your criteria when picking a railroad company. Let’s make the comments of this article a place where we can share valuable information.

Be the first to comment