Richard Drury/DigitalVision via Getty Images

Warren Buffett once quoted economist John Maynard Keynes:

“I would rather be vaguely right, than precisely wrong”

This idea has guided my investing philosophy for a long time.

Mathematics, physics, chemistry, and astronomy admit absolute precision in their results. They are exact sciences.

Investing, on the other hand, is anything but.

Many investors put too much emphasis on precision and accuracy when they should merely seek to be directionally correct.

They focus too much on trailing financial metrics, leading to value traps or missed opportunities.

Investors don’t get paid for the past, only the future. As a result, the capacity of a business to generate cash sustainably is critical.

Warren Buffett explained in 2007:

“If we see someone who weighs 300 or 320 pounds, it doesn’t matter — we know they are fat. We look for fat businesses.”

And Charlie Munger added:

“When you’re trying to determine intrinsic value and margin of safety, there’s no one easy method that can simply be mechanically applied by a computer that will make someone who pushed the buttons rich. You have to apply a lot of models. […] We have no system for estimating the correct value of all businesses. We put almost all in the “too hard” pile and sift through a few easy ones.”

I often find articles claiming a stock is a buy at [insert arbitrary price target] or is undervalued by [insert random percentage]. It’s baffling to me.

When I assess an investment opportunity, I usually want to see evidence that I could double my money within the next three to five years, which is more than enough to generate market-thumping returns.

This approach encourages me to favor buying a wonderful company at a fair price instead of a fair company at a wonderful price.

My filters, checklists, and screeners mainly stem from qualitative factors. I borrow many of these factors from legendary investors such as Peter Lynch, Philip Fisher, Warren Buffett, and Howard Marks.

Among other things, I look for:

- Scalability.

- Unique culture.

- Recurring revenue.

- Competitive advantage.

- Best-in-class leadership.

- Significant addressable market.

- Ability to create new revenue streams.

- Strong track record of outperformance.

An analyst cannot reflect these traits in a spreadsheet in a way that would do them justice. Therefore, the spreadsheet is the last place I want to focus on.

Charlie Munger said in a 1996 Berkshire Hathaway annual meeting:

“Warren often talks about these discounted cash flows, but I’ve never seen him do one…”

Buffett added:

“That’s true. It’s sort of automatic. If you have to actually do it with pencil and paper, it’s too close to think about. It ought to just kind of scream at you that you’ve got this huge margin of safety.”

Yes, Buffett is famously known for not using a calculator.

A top-down appraisal often supersedes a bottom-up valuation.

A discounted cash flow analysis may give the illusion of security by extrapolating existing trends and assuming a linear deceleration. However, such a model often overlooks the qualitative reasons that might justify an investment in the first place.

Charlie Munger to add:

“Some of the worst business decisions I’ve ever seen are those with future projections and discounts back. It seems like the higher mathematics with more false precision should help you, but it doesn’t. They teach that in business schools because, well, they’ve got to do something.”

To avoid false precision and the illusion of security, seeking to be vaguely right can help us ask the right questions.

- What will happen if I’m wrong?

- Is this investment suitable for me?

- Will this business be larger in 10 years?

- What needs to go right for me to make money?

- Is my portfolio prepared for a wide range of outcomes?

Let’s review how the art of being vaguely right can help investment selection, portfolio construction, and goal setting.

The right kind of bet

If you seek to be directionally correct, you’ll soon realize that it eliminates many potential investments relying on an impending binary outcome.

We see exceptional volatility around significant events such as Fed minutes or quarterly earnings reports.

Why? Traders and gamblers bet on inflation, interest rates, macro developments, company earnings, or other short-term catalysts. But, unfortunately, they are all impossible to predict with accuracy.

My filter here is simple. Before making an investment decision, I ask: Could I be proven wrong in days or weeks? If so, my investment idea is likely too binary and is more akin to gambling.

Investing and gambling both involve risk and choice.

However, they are fundamentally different:

- Investing is rigged in your favor through dividend re-investing and compound interest. You can adjust your decision through position sizing as we gain evidence of success.

- Gambling is rigged against you. It heavily involves chance. You are betting against other gamblers with the potential gains offset by fees, risk mitigation costs, and tax inefficiencies.

An unprecedented number of people treat the stock market like a casino. They buy an asset in the hope of selling it at a higher price without any regard for the value of the underlying business.

Paul Samuelson explained:

“There is something in people; you might even call it a little bit of a gambling instinct… I tell people investing should be dull. It shouldn’t be exciting. Investing should be more like watching paint dry or watching grass grow. If you want excitement, take $800 and go to Las Vegas.”

If you can play the game on your terms and focus on a longer time horizon, you can stack the deck in your favor. And it starts with letting an investment play out over several years.

Ultimately, investing is a waiting game. So we need to let the story play out over an extended time.

Buying or selling is a false dichotomy. Too often, investors are forced into a corner and lean toward action when they should lean toward inaction.

They are either in or out. Right or wrong.

The truth is usually somewhere in between.

Playing long-term games is the very premise of seeking to be vaguely right.

Not always worth it

I covered in a recent article the importance of inversion and how it can help you avoid single points of failure.

The premise is simple. We can solve a problem by addressing it backward. For example, figuring out which stocks to avoid can be easier than finding which ones will outperform.

I previously offered 10 Reasons Not To Buy A Stock.

The game of avoidance is crucial because most stocks underperform the market by a wide margin.

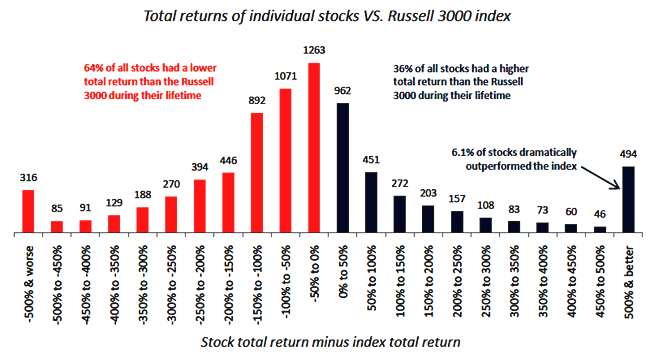

Blackstar Funds have reviewed the historical distribution of 8,000 stocks trading on the NYSE, AMEX, and NASDAQ over 23 years (1983 to 2006).

The results? 64% underperformed the index during their lifetime.

Distribution of stock returns 1983-2006 (Blackstar Funds via Meb Faber)

So instead of trying to strike gold with unknown micro caps or obscure businesses with limited public information, investors should recognize their odds of success.

The bar for a stock to be considered for your portfolio should be extremely high. Therefore, it’s critical to be skeptical and focus on the best ideas.

In order to be loosely correct, we are more likely to seek not to be wrong.

With so many stocks to choose from and the vast majority underperforming, it’s essential to realize that most stocks are not worth your precious time.

Buffett explained:

“That which is not worth doing at all is not worth doing well.”

Going into deep research or valuation models is pointless if a company is not good enough to be deemed investable.

In investing, a stock is guilty until proven innocent.

The limits of discounted cash flow

The valuation of a business ultimately depends on future cash flows.

So a DCF model can help you determine if you are paying a silly price and what needs to go right to make a good return.

However, discounted cash flow models are flawed and depend on our assumptions.

Complex valuation models give the illusion of comfort and accuracy.

The main problem?

They require many assumptions about the future, which implies a high potential for errors and overcomplexity.

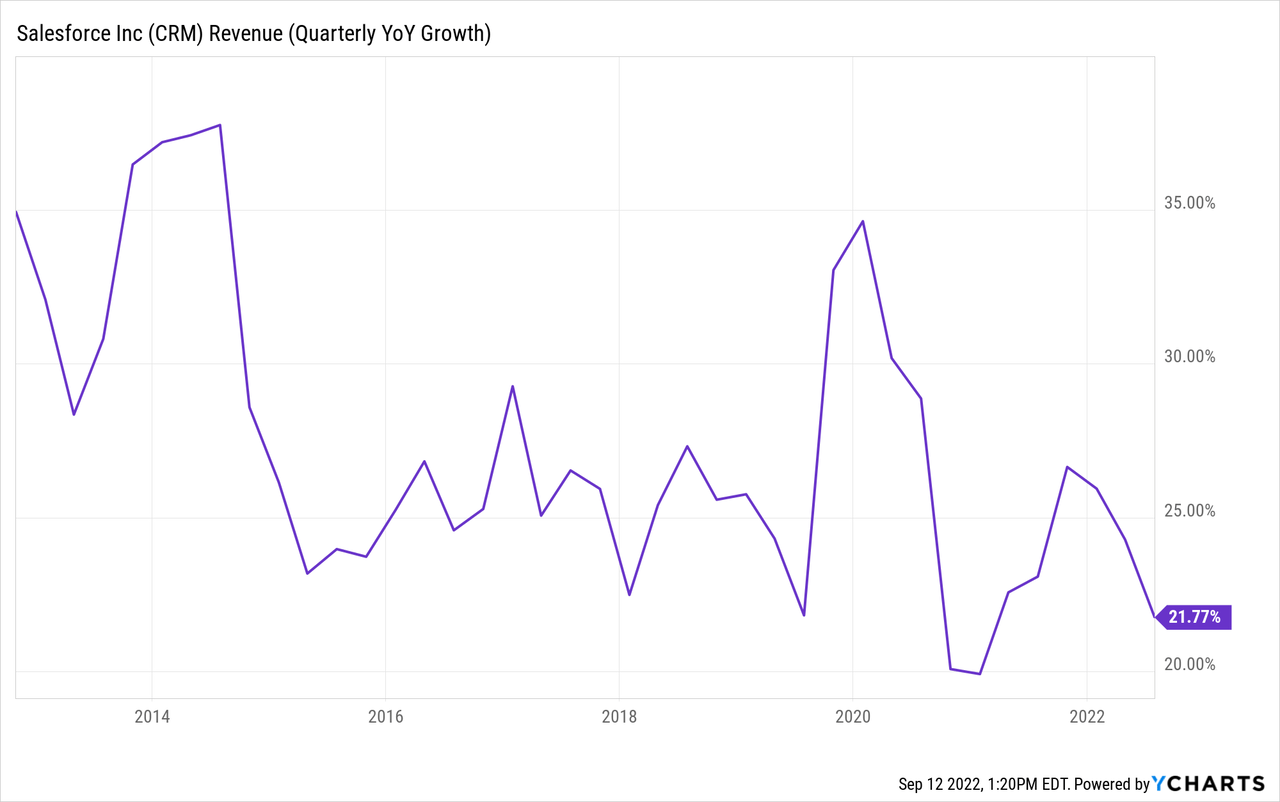

How many models built ten years ago would have assumed that Salesforce (CRM) would still be growing revenue north of 20% Y/Y in 2022?

Probably none.

Building a detailed DCF for Amazon (AMZN) in 2005 would have been useless because it would have ignored the future release of AWS (Amazon Web Services). The cloud infrastructure segment justifies most of the company’s valuation today.

Similarly, Google (GOOG) (GOOGL) acquired YouTube two years after becoming a public company. Again, nobody could have foreseen the benefit of this acquisition in prior models.

Any discounted cash flow model built for Apple (AAPL) before 2007 would have ignored the existence of the iPhone, the iPad, wearables, or services like the App Store, Apple Pay, and subscriptions.

Based on the above examples, the futility of projecting a company’s performance over ten years should be obvious.

Success is not linear. A business could strive or struggle in five years for unforeseeable reasons.

I like to point to HubSpot (HUBS), a four-bagger in the App Economy Portfolio since 2017. HubSpot CMS (web content management software) launched in April 2020. And today, it’s the leader in Web Content Management in just two years. CMS itself was never part of my initial bull case, but I invested in the company for its track record of innovation. This is what optionality looks like.

When you invest in innovative teams, your investment can flourish for reasons not included in your initial bull case.

That’s what I call stacking the deck in your favor.

Unless you are investing in specific sectors like energy, materials, or industrials, building a 10-year projection is a humbling experience at best.

Imagine making claims that a company is overvalued based on your own estimate of how much cash flow it will generate in 10 years.

Dozens of full-time analysts on Wall Street can’t predict the next quarter with accuracy. So why on earth would you believe you can forecast a company’s performance over several years, let alone several quarters?

If we can’t predict what will represent the majority of a company’s revenue in 10 years, the futility of accurately predicting its cash flows should be obvious.

In addition, greatness cannot always be quantified in a model, leading to the perception that an outstanding business is overvalued.

Consider these traits:

- Optionality.

- Capacity to innovate.

- Durability of revenue growth.

- Quality of leadership and culture.

- Sustainability of an economic moat.

Without making assumptions out of thin air, there is no way to implement these traits accurately in a discounted cash-flow model.

This is particularly true for businesses still in their hyper-growth phase. As a result, it can lead to dramatic mispricing of equities over time.

Understand the business and its maturity

In his book One Up On Wall Street, Peter Lynch covers stock picking and what it means to be a shareholder.

Lynch puts companies in six categories:

- Slow Growers (mature companies like AT&T (T)).

- Medium Growers (stalwarts like Coca-Cola (KO)).

- Fast Growers (growing above 30% Y/Y like Snowflake (SNOW)).

- Cyclicals (e.g., Southwest (LUV)).

- Turnaround (struggling companies that may provide temporary opportunities, such as Peloton (PTON) recently).

- Asset Plays (companies trading below book value).

Valuation metrics such as P/E (price/earnings) or PEG (price/earnings to growth) can be entirely useless – even on a forward basis – if you are looking at a company with a long way to go before reaching maturity.

Some companies may be re-investing aggressively in themselves with high R&D costs. Or they might try to expand their market share rapidly because they know that they can offset their user acquisition costs over the lifetime value of a customer. These insights can only appear with proper due diligence.

Brian Feroldi shared the chart below showing the different stages of the life of a company and its corresponding P/E ratio.

| Stage of the business | PE ratio | Use-case | Duration |

| 1) Introduction | Negative | Useless | 0-20 years |

| 2) Hyper-growth | Very High | Semi-Useless | 1-10 years |

| 3) Maturity | Normalized | Useful | 1-50+ years |

| 4) Decline | Very Low | Useless | 1-10+ years |

| 5) Death Spiral | Negative | Useless | 1-10+ years |

For companies still in stage 1 (introduction) or stage 2 (hyper-growth), trying to use a P/E ratio becomes useless. If you are screening for stocks solely based on their P/E ratio (or price to free cash flow), you will exclusively invest in companies already in stage 3 (maturity). You will often feel tempted to invest in companies in stage 4 (decline) just because they appear “cheap” without even realizing it.

You may fall in love with a company “out of favor” because it has low PE. This is because it can give the illusion of a margin of safety. But if the company is on a secular decline, it could soon turn its slowing profits into losses, and the value play will turn into a value trap when they enter stage 5 (death spiral).

I’ve illustrated before how some companies may appear ridiculously overvalued if you don’t look closely at the underlying business. The valuation always needs to be put in context.

The long-term potential of a business matters immensely more than its valuation at any given time.

While valuation gives you a sense of your margin of safety on the way down, the quality of the underlying business gives you a sense of the scope of the opportunity on the way up.

Suppose you seek to make only bets with very high certainty in what the future may hold. In that case, you’ll likely limit your investments to mature businesses and overlook the potential for their decline, leading to value traps.

Conversely, if you accept to let go of what you cannot predict and embrace the uncertainty, you open up for investments with more significant upside potential.

The art of being vaguely right means opening up to being wrong. It’s a requirement for wealth accumulators.

Focus on the market cap and the opportunity

Many investors focus too much on the price of a security and not enough on a company’s market cap. They focus on where a stock has been over days, weeks, and months or make blunt claims about how much it could fall without realizing they are simply anchoring their expectations.

I try to answer two simple questions:

- What is the market cap of the company today?

- How big is the opportunity ahead?

I want to own a company that is still relatively small compared to the opportunity at play within a secular trend that could go on for years.

Let’s cover some examples:

- CrowdStrike (CRWD) is a category-defining cloud security company. Today, it’s a ~$44B company. Management expects to cross $5B in annual recurring revenue by 2026, and the total addressable market is estimated to grow from $25B in 2019 to $126B in 2025.

- Datadog (DDOG) is a best-of-breed monitoring and analytics platform. It’s a $33B company today. Observability alone (its core market) could reach $53B in 2025. Future opportunities in security, developer workflows, real-time business intelligence, or IT service management could continue to expand its potential.

- Airbnb (ABNB) is an $80B giant today. However, the platform has more listings than all the leading public hotel chains combined. Furthermore, one night out of five booked on Airbnb is part of a trip that’s 28 days or longer. It involves new lifestyle hotels don’t compete for. The company is reinventing hospitality with longer stays and network effects at play.

The list goes on.

Again, what matters to me is to be directionally correct.

Given the size of the market cap and the opportunity, I should be able to confidently say that the business could get a lot bigger over time.

Compare to peers

An easy way to put a company’s valuation in context is to compare it to its peers. Of course, it won’t keep you from investing in an inflated market or sector. Still, it will help you see if a company is trading at a premium to similar businesses and help you identify the premium you are paying.

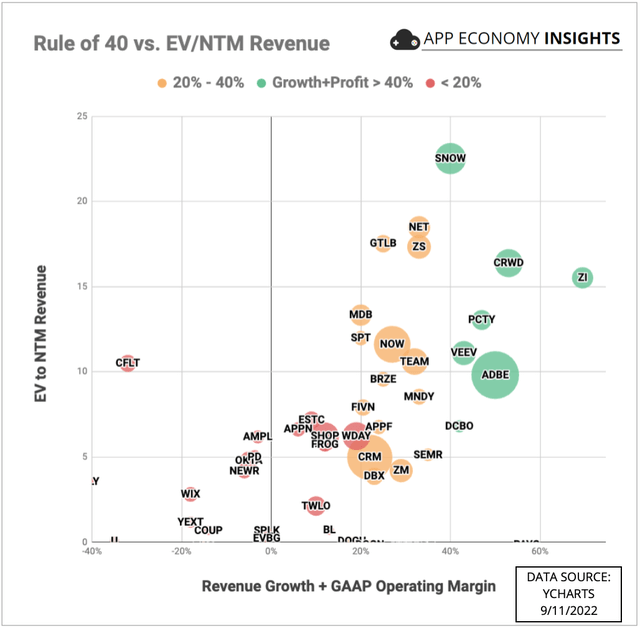

I love to think about the companies I analyze in “clusters.”

Long-time readers are familiar with my chart putting revenue multiple against revenue growth and operating margin in the same chart.

Rule of 40 vs. EV/NTM Revenue (App Economy Insights)

There are many complementary steps to consider:

- What is the net revenue retention?

- What % of the revenue is recurring?

- What is the gross margin profile of the business?

- Does the company have a history of adding new products and services?

Some companies may appear similar initially, but that’s not always the case. Proper due diligence can help appreciate why a company trades at a premium.

By comparing to other leading cloud infrastructure businesses, you might notice that AWS alone could justify the market cap of Amazon. As a result, I don’t need many things to go right for an investment in Amazon to deliver significant returns.

In effect, I’m asking: Am I in the right ballpark? If not, I will move on.

Look for mature businesses in the same field

One of my favorite ways to evaluate the long-term potential of a business is to find a company that had a similar profile years ago and see the price appreciation since then. It helps put my targeted investment in context.

Mature cloud companies like Workday (WDAY) or ServiceNow (NOW) can indicate what to expect based on their metrics when they hit previous revenue milestones.

For example, Snowflake is on track to be the fastest company to reach $10B in annual recurring revenue. So when I think about how big Snowflake might become in the decade ahead, I look at companies that have reached such a scale and their profile when they hit similar revenue milestones.

To illustrate, Adobe (ADBE) was a $134B company by the time it reached $10B in revenue. And it never had a growth profile even remotely close to Snowflake. This comparison helps me consider my margin of safety and upside potential before investing.

I find it hard not to see the potential for excellent returns if management can deliver the long-term target. And given that SNOW has beaten expectations by 6% on average over eight quarters since going public, the company has the track record to back up its projection.

Some investors will solely focus on an arbitrary valuation metric or obsess over stock-based compensation. But, in my view, they are missing the forest for the trees.

What about the downside risk, you ask?

It can be monitored with position sizing. The wider the range of outcomes, the smaller the position should be.

Look at the valuation spectrum over time

It’s essential to understand how the company has been valued over time to identify whether we are buying at the peak of the hype.

To do so, I like to look at the valuation spectrum over several years.

I’ll be happy to use an earnings or cash flow multiple for a profitable company. However, a revenue multiple will do for a company that is still losing money or close to breakeven.

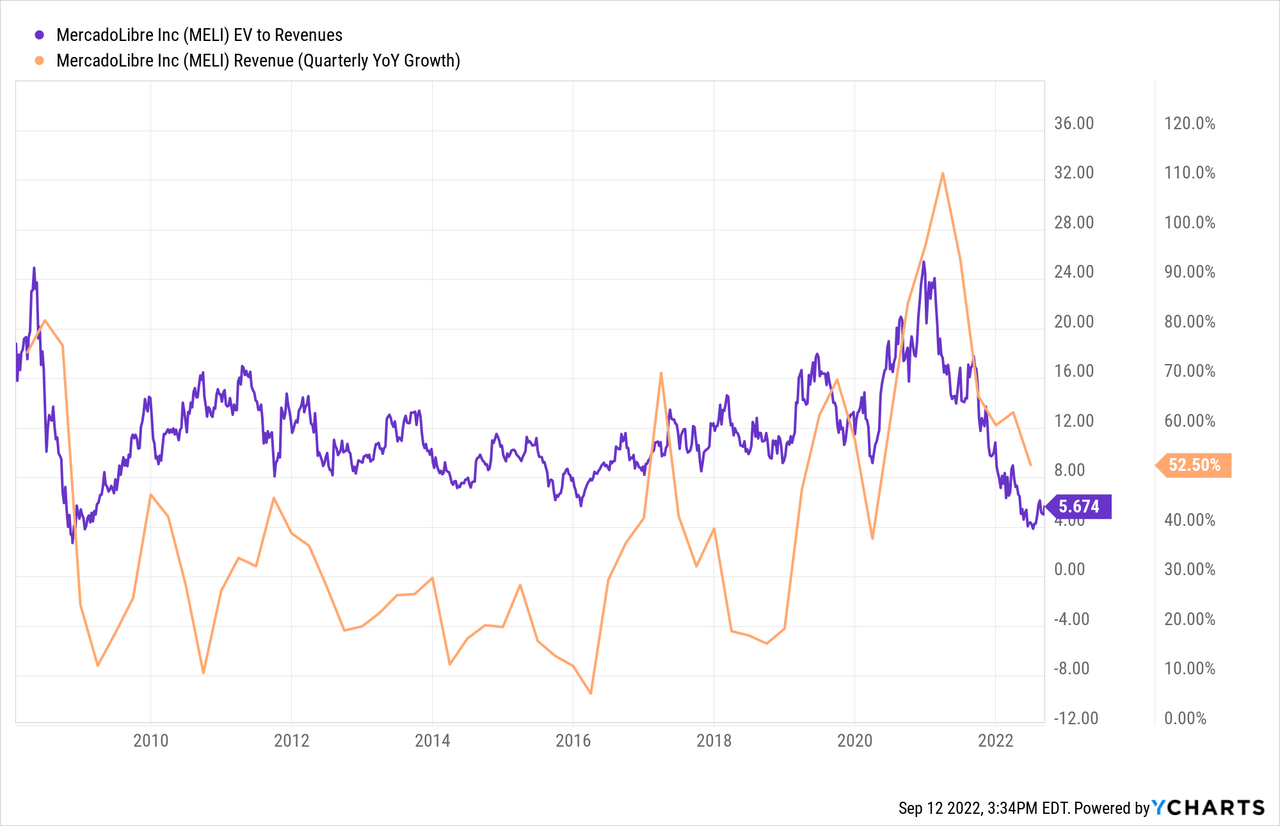

Let’s look at MercadoLibre (MELI) and how the company has been valued in the past 15 years.

MELI is growing faster today than it did in most of its time as a public company, and it’s also trading close to a 15-year low from a revenue multiple perspective. Additionally, the growth of its fintech segment has a long runway and represented less than half of the top line in Q2 FY22.

It doesn’t take a genius to see that MELI offers a compelling entry point in 2022. Sometimes, a chart is worth a thousand words.

Finding the right risk/reward balance

Investing in growth stocks requires accepting we don’t know what the future may hold with precision.

Howard Marks released an excellent memo covering the art of finding a company’s intrinsic value in this day and age and the false dichotomy of value and growth.

On the risks associated with investing in growth stocks, he explains:

When they’re rising, growth stocks typically incorporate a level of optimism that can evaporate during corrections, testing even the most steeled investor. And because growth stocks depend for most of their value on cash flows in the distant future that are heavily discounted in a DCF analysis, a given change in interest rates can have meaningfully greater impact on their valuations than it will on companies whose value comes mainly from near-term cash flows.

As a result, with years needed for the beauty of compounding to do its magic, the stomach needed to be able to cope with large draw-downs is an essential tool in the arsenal of the growth investor.

If you know you don’t have the stomach for it, investing in a growth stock may be a poor investment. The idea of investment suitability is often overlooked. Not all investment styles can fit your temperament.

At the core of successful investing, Marks points out the need for superior judgments concerning:

- a) qualitative, non-computable factors.

- b) how things are likely to unfold over time.

He encapsulates perfectly the immense investment opportunities before us, and how they are matched by risks of disruption.

On the positive side, successful businesses have much more potential for long runways of high growth, superior economics, and significant durability, creating a huge pot of gold at the end of the rainbow and seemingly justifying valuations for the potentially deserving that are off-puttingly high by historical standards.

On the negative side, it also creates immense temptation for investors to overvalue undeserving companies. And companies with here-and-now cash flows and seeming stability can see those evaporate as soon as a bunch of Stanford computer science students get funding and traction for their new idea.

He points out that skepticism – inherently a quality for any investor – can lead to “knee-jerk dismissiveness.” Finding your footing between proper due diligence, critical thinking, and willingness to pay 20 times forward revenue can require quite the balancing act.

The truth is likely somewhere in between.

Some of today’s lofty valuations are probably more than justified by future prospects, while others are laughable – just as certain companies that carry low valuations can be facing imminent demise, while others are just momentarily impaired.

The challenge is that nobody knows with certainty what the future may hold. In hindsight, some look like geniuses, while others look like fools. Taking the risk to look like one or the other is when your investing journey truly begins.

Seeking reasonable outcomes

Realizing you can always be wrong, at least on certain aspects of your thesis, should lead to better decisions for portfolio management.

Diversification is “the only free lunch” in investing, a quote attributed to Nobel Prize laureate Harry Markowitz. Behind this quote is the idea that diversification can significantly reduce the risks without compromising returns.

Most investors are well-versed in the idea that they need to build their portfolio on the efficient frontier with the right risk-reward balance.

I tried to answer a simple question in a previous article: How many stocks should you own? The correct number is different for everyone.

In his book The Psychology of Money, Morgan Housel explained the difference between rational and reasonable.

A rational decision means deciding based on the facts and numbers. It all sounds great in concept. The implication is that you let the data decide for you. However, being rational is not always a realistic approach. We all have emotions at play that can get in the way of a sound plan. Sometimes, what would make the most sense for you will be different from the most rational decision. Instead, you need to define what is reasonable for you.

The proper diversification is the one that keeps you in the game over multiple market cycles. That’s why portfolio suitability is so essential.

The proper amount of diversification is the one you can stick with for decades on end. Finding adequate allocation by geography, sector, or category is a matter of personal preference.

The more you know what you’re doing and the more certainty you have about a specific investment, the higher your concentration can be.

It’s essential to use diversification as a safeguard to prevent you from getting in the way of your portfolio’s success.

For example, I only allow myself to add to an individual stock up to a certain point. After that, I comply with a max allocation on a cost basis (initial funds added to a single investment). After that, I let it run and let my portfolio concentrate.

If you focus on your risk allocation from a cost-basis perspective rather than your current value, you will benefit from two leverages:

- It will prevent you from adding too much to your losers.

- It will encourage you to add to your winners, even if they have run a lot.

A rule-based approach to diversification can be a lifesaver when emotions run high in the heat of the moment.

The role of diversification is to make sure you stay in the game under all circumstances and keep the compounding of your returns uninterrupted.

Seeking to be vaguely right also involves being able to say, “I don’t know.”

People endlessly try to make market predictions. They claim that “stocks have more to fall” or “don’t see any upside in the near term.” This type of reasoning is, at best, an opinion. In his book The Most Important Thing, Howard Marks explains:

“If you can’t predict the future, the most important thing is to admit it. If it’s true that you can’t make forecasts and yet you try anyway, then that’s really suicide.”

It’s impossible to know what will happen in the near term. So if you catch yourself trying to guess what stocks might do next week, today is a great day to remember that it’s a waste of time. You can’t!

Don’t seek to make bold claims about unpredictable developments. Instead, seek to be vaguely right by considering all possible outcomes.

Leave that crystal ball aside, and appreciate the role of luck in your investing journey. Because once you do so, you are empowered to maximize the odds in your favor.

Bottom Line

Too many investors hide behind spreadsheets to make an investment decision.

The false precision and illusion of security of arbitrary valuation metrics focused on the past is a recipe for disaster.

Common sense, intuition, and qualitative factors go a long way in avoiding investing pitfalls.

Aiming to be vaguely right can simplify an otherwise overwhelming task. And it can help us make smarter decisions along the way. But, more than the destination, it requires us to ask ourselves if we are aiming in the right direction.

What about you?

- What makes you select an investment?

- How do you make sure you are on track with your goals?

- Do you seek binary outcomes or focus on long-term games?

Be the first to comment