lorozco3D

By Patrick Bradley

Over the last two years, inflation around the globe has returned with a vengeance, testing central bankers’ tools and risking economic growth. Inflation has remained higher for longer than had been expected, leaving many to wonder if it will become as entrenched as in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Central bankers want to nip inflation before it becomes entrenched, but their one-dimensional monetary approaches are limited against the complex, multi-faceted nature of today’s inflation. The harsh medicine of a recession may be the only cure.

A Brief History of Inflation

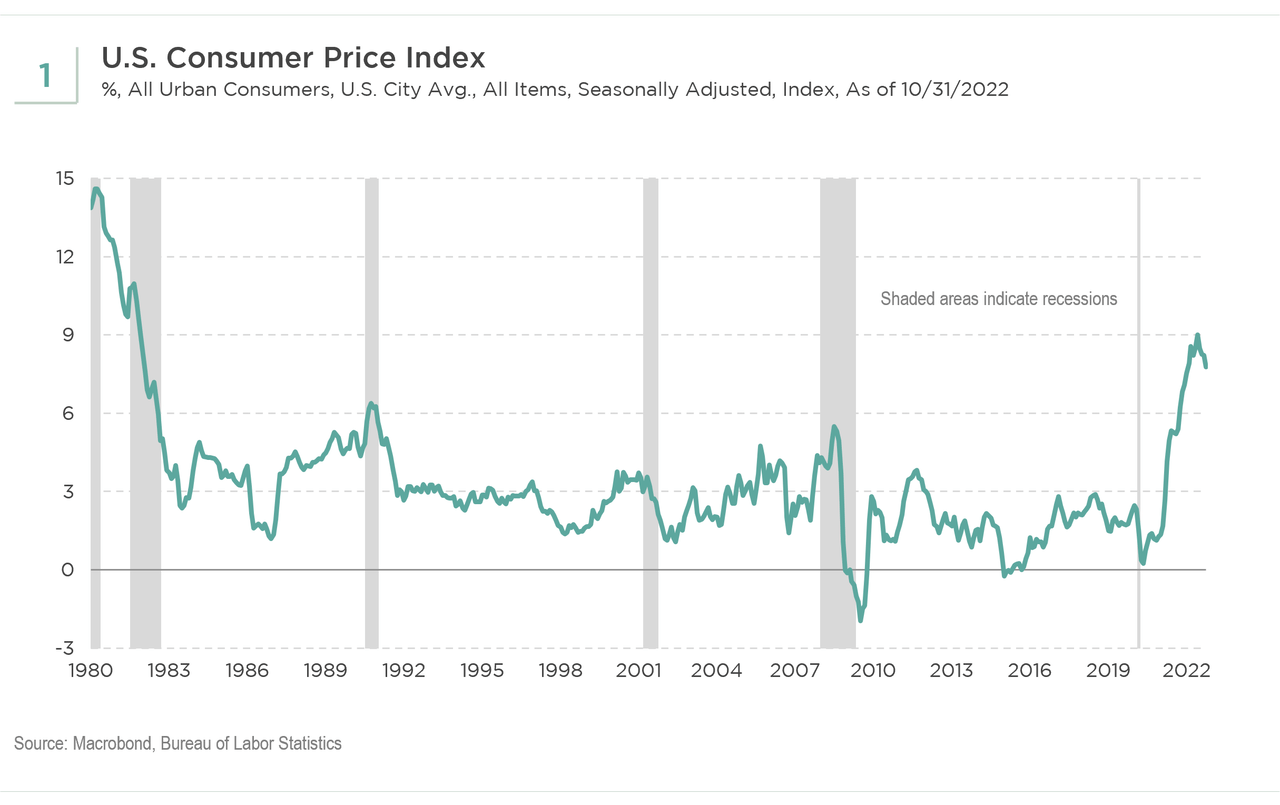

The recent history of U.S. inflation, for example, shows it to be relatively well-behaved as the Federal Reserve focused on hitting a targeted 2% rate of inflation. But in the rear-view mirror just behind this recent view of inflation is the experience of the early 1980s, when then-Federal Reserve (Fed) Chairman Paul Volcker was credited with staunching consumer price inflation from a peak of nearly 15% year-over-year. Even with the 2% target, inflation remains highly cyclical (see Figure 1). Price pressures typically rise during an economic expansion, largely driven by demand, supply, and monetary forces. However, inflation-targeting by the Fed typically brings inflation to heel through a higher policy rate and, lately, through quantitative tightening. Other central banks can tout similar success with keeping a lid on inflation.

Macrobond, Bureau of Labor Statistics

A Toxic Inflation Stew on the Boil

Now let us move to the present and drill down on the world’s current bout with inflation that appears stubborn. Looking at the period from 2020 to now in Figure 1, what hit economic activity in 2022 was the onset of the devastating COVID-19 pandemic that for a period shut down the global economy. The stay-at-home workforce was born, as millions of workers left offices and worked remotely. The economy entered a brief recession in March, as the chart shows. The inflation rate fell to about 24 basis points by May 2020. The Fed reacted, pushed the federal funds rate to 0%, and initiated a program of quantitative tightening. Other countries pursued similar courses of action.

Concurrent with the monetary easing, the U.S. federal government, along with most countries, undertook sizeable stimulus programs to help families and businesses weather the pandemic-induced storm, which included both weakening demand and rising unemployment. The Trump administration initiated the U.S.’s first fiscal response. The new Biden administration added more stimulus to the economy with the American Rescue Plan that included a national vaccination program and a scaled-down version of the president’s Build Back Better program.

Suffice it to say this stimulus introduced a tremendous amount of liquidity, combining both fiscal and monetary pump priming. The U.S. personal savings rate skyrocketed to 35%, with similar surges across the developed world. At the same time, production was being scaled back, falling some 17% by April 2020, and inventory investment dropped. A potentially toxic inflation stew was now brewing. You had demand-pull pressures from the fiscal stimulus, cost-push pressures from inventory disinvestment, and surging money supply. Inflation hit the highest rate in about 40 years, as shut-in consumers had money to burn.

Where Are We Now?

Inflation eventually hit an uncomfortably high rate. What aggravated the building inflationary pressures was a dismissal, especially by Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, that inflation was not a problem. It would be transitory. Unfortunately, it was not. The slow Fed response allowed price pressure to build. The Fed started its hiking cycle in March 2020, but soon realized it was behind the proverbial curve. Then, the economic environment became more complicated with the invasion of Ukraine by Russia. Quoting an overused but apt reference, a perfect storm hit. The Ukraine War cemented the negative inflation outlook, particularly for Europe with its high dependency on imported Russian gas and oil. In short, consumers were flush with cash and had a desire to spend it on cars, on houses, and more. Yet, even as demand rose, supply constraints became more widespread, affecting automobile production, with the industry experiencing semiconductor shortages, and houses, with lumber prices rising rapidly.

Macrobond

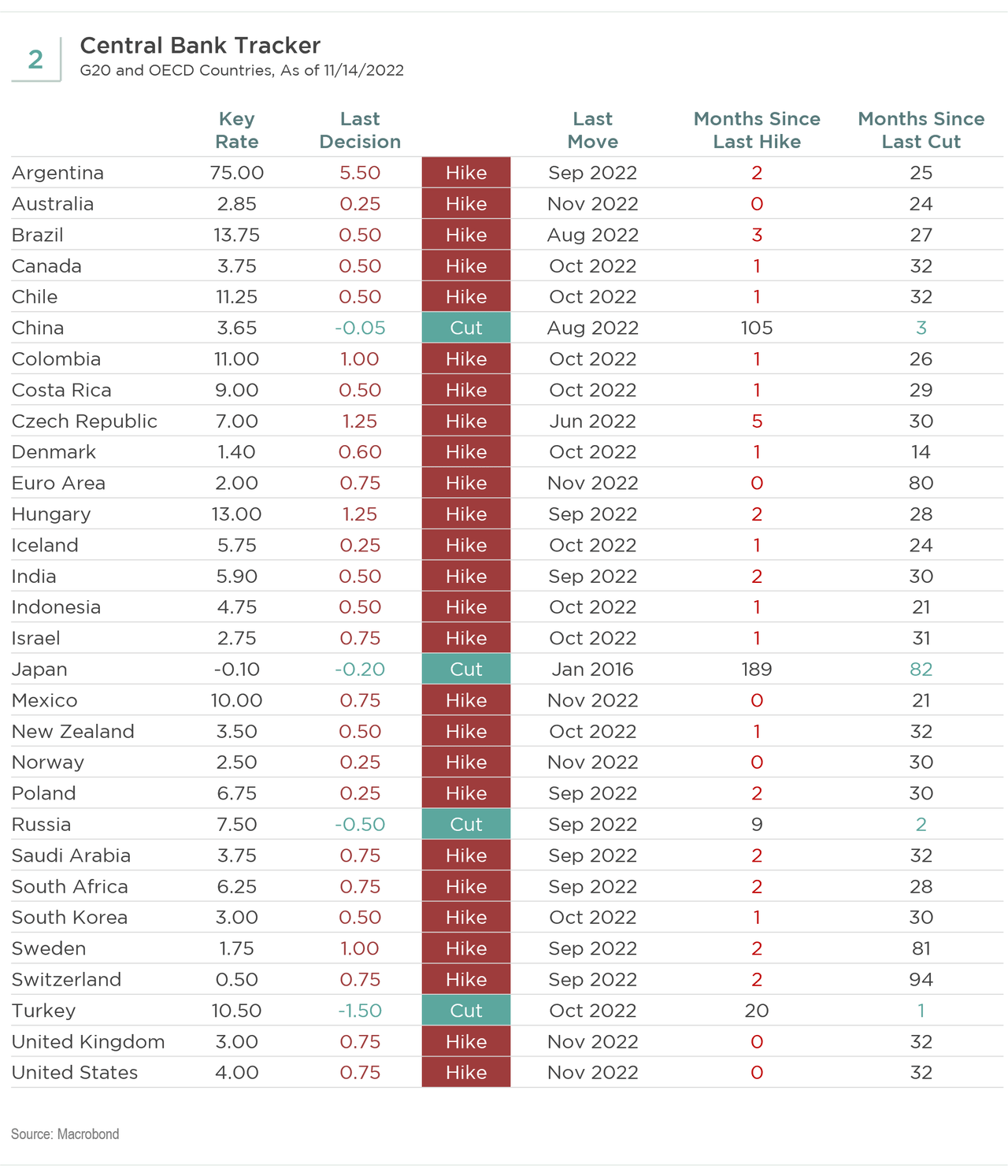

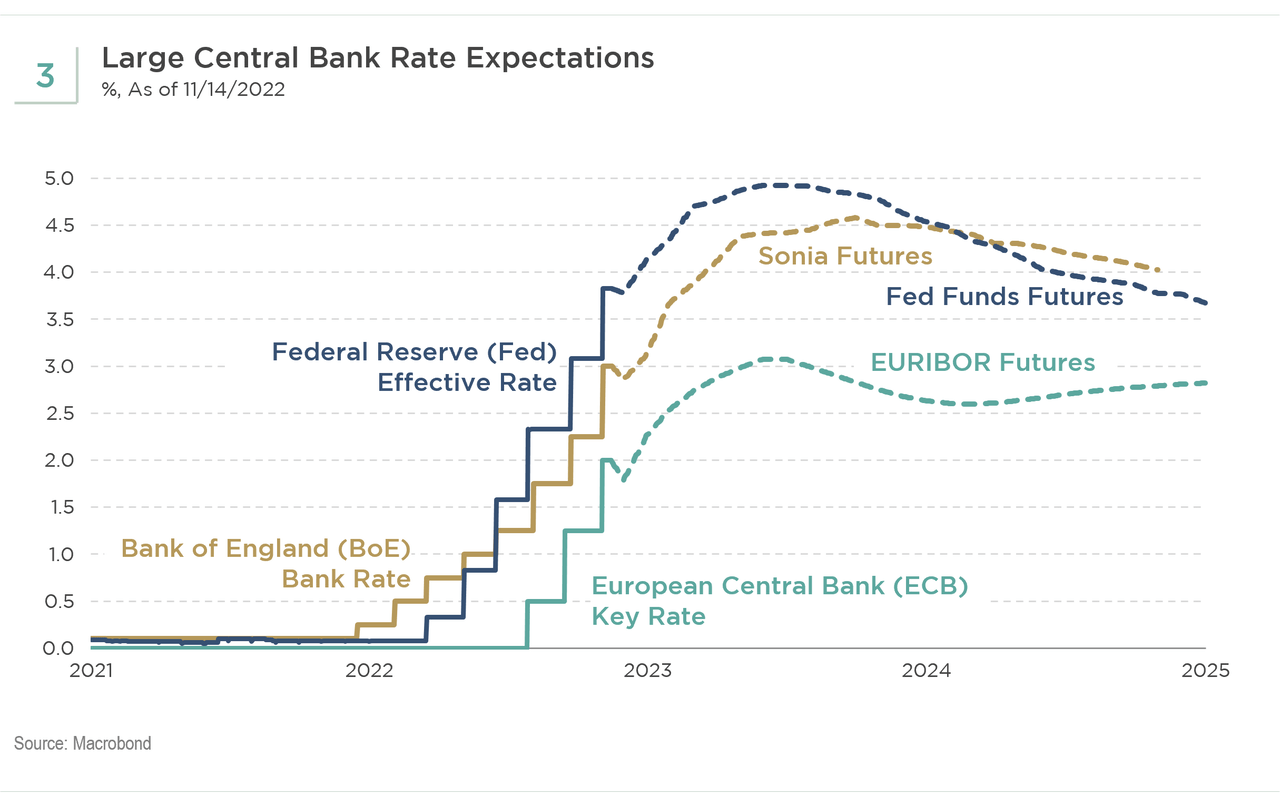

The resulting inflation set off rounds of global central bank hikes (see Figure 2). The Fed hit the U.S. economy with several rounds of 75-basis point hikes, and the European Central Bank (ECB) pushed its policy rate 200 basis points above zero. Most central banks started hiking and draining the pandemic liquidity, and many remain in tightening mode. Brazil, for example, was among the earliest banks to raise its policy rate. Other countries followed. However, broad monetary tightening raises the specter of recession, particularly in regions like the eurozone and the U.S. There are, of course, exceptions to the global hiking cycle, notably China, Japan, Russia, and Turkey. Not surprisingly, the tightening by global central banks created bear markets in risk assets. Figure 3 shows the extent of tightening that has occurred and is expected to continue by the Fed, Bank of England (BoE), and ECB as reflected in the futures markets. The Fed appears to be the most aggressively tightening bank, with market rate expectations reflecting significant hiking by three of the world’s largest central banks.

Macrobond

Assessing Next Steps

As an example, what could the Fed be seeing? Is inflation near a peak, and could the Fed be near the policy pivot point, despite Powell’s admonition to the contrary? The Fed chairman has remained unwaveringly hawkish, providing no guidance on whether rate hikes will slow. Chairman Powell appears more focused on demand inflation, upon which central banks can have an impact. The Fed’s actions will weigh more heavily on demand-driven and monetary inflation. However, a driver of the current inflation has come from the supply side, which monetary policy cannot affect. Higher interest rates and quantitative tightening will not produce one more semiconductor. Nonetheless, we have seen some demand destruction and some loosening of supply constraints. Recent signs, based on the U.S. Consumer Price Index (CPI) and weakening energy prices in the euro area, indicate a topping process.

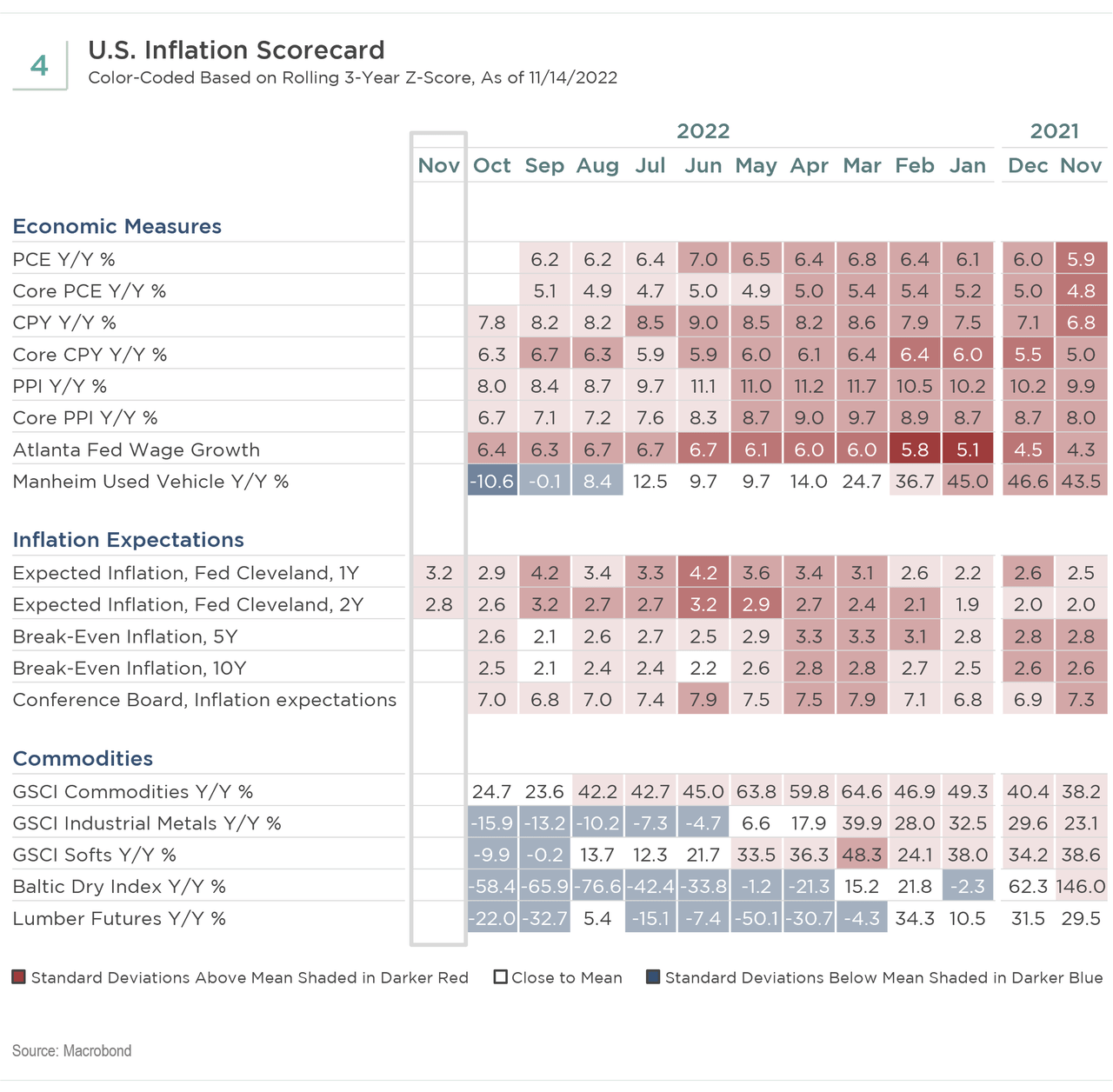

The Fed is having some success in its inflation scorecard (see Figure 4). The fourth quarter of last year saw inflation accelerating. More recently, inflation appears to have peaked, depending on the measure, partially due to Fed policy. However, headline CPI at 7.8% in October is far from the goal of an average 2% rate. In the absence of clear signs of a recession, including rising unemployment, the current inflation rate does not augur any shift to easing by the Fed–or any central bank. Instead, it may only suggest smaller future rate hikes, with an easing cycle being initiated in the third quarter of 2023. In sum, inflation has receded, but it remains too high.

Macrobond

Central banks need to be concerned about inflation expectations becoming unanchored. That could contribute to a wage-price spiral, as workers bargain to catch up to inflation and businesses on the higher cost of production. Should this situation occur, that might argue for even tighter monetary policy, which could ensure a deep economic downturn. On the positive side, most measures of inflation expectations are below 3%. However, they are higher than the 2% average inflation target the Fed currently maintains, which does suggest that markets are expecting somewhat higher inflation, and that could negatively affect asset prices. It might also be argued that central banks should target a higher rate of inflation going forward.

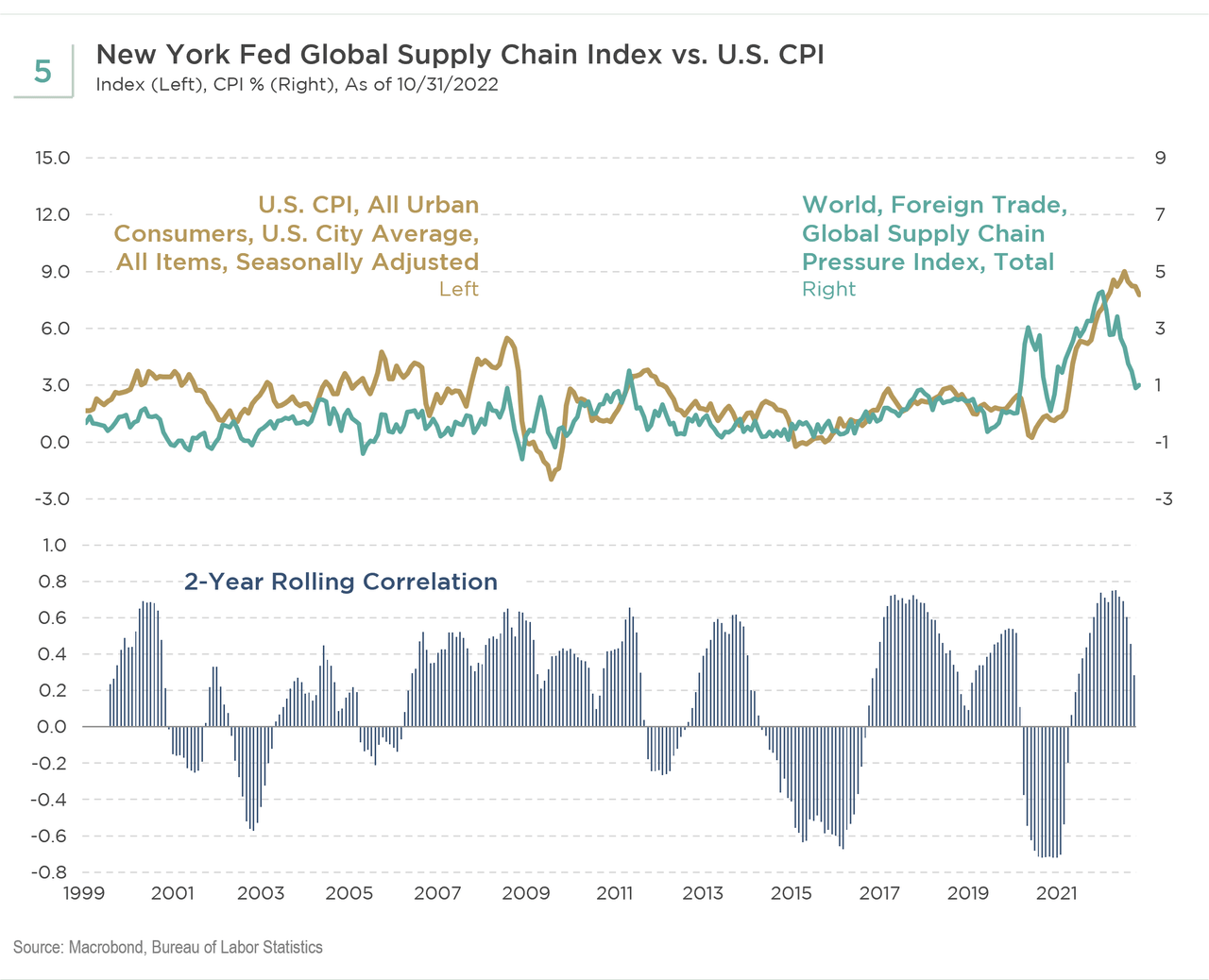

Finally, near-term inflationary pressures appear to be easing. Central banks, like the Fed, can only take partial credit for the recent drop. Supply-side constraints were a significant contributor to our recent bout of inflation and, as noted already, supply-side pressures cannot be alleviated by monetary policy – the price system does that. However, supply-side pressures appear to be easing rather dramatically. Comparing the New York Federal Reserve Bank global supply chain index to headline CPI indicates supply pressures, like shipping rates, are easing (see Figure 5). Those moderating price pressures are a harbinger of lower inflation. The verdict on inflation is it is falling but the question remains whether inflation targeting will return inflation back to the desired average inflation rate. Some of us are doubtful.

Macrobond, Bureau of Labor Statistics

Conclusions

- Inflation appears to be falling even though monetary policymakers were slow to react to the onset of price pressures. Such pressures had been absent from the developed world for some time, and it is possible there might have been some complacency among many of the world’s central bankers.

- Given the recent inflation episode, is the current regime of inflation targeting the appropriate policy goal of central banks, including the Fed? The earlier success of inflation targeting argues that it is a policy worth maintaining. It may be that the “success” could be due to external events like China entering the World Trade Organization (WTO), offering the world low-priced goods. Central banks cannot control inflation directly but can only indirectly impact it through their policy tools.

- Inflation targeting risks a policy error. The Fed – and all central banks – need to understand what is generating the price pressure. In this latest inflation episode, policymakers seemed to ignore the supply-side contribution to inflation and, instead, applied its demand-destruction policy of higher rates.

- Looking forward, central banks may have to consider a higher inflation target. For example, the transition to a net-zero economy has the potential to increase inflation, and a 2% (average) rate may be difficult to hit. Additionally, workers have been demanding higher pay. A higher inflation target would move the policy rate further above the zero bound, giving central banks, like the Fed, more room to ease monetary policy in the event of a recession.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment