naphtalina/iStock via Getty Images

July CPI readings showed inflation (both at a headline (0% Month-on-month (MOM) in July-22 compared to 1.3% MoM in June-22 and core level (0.3% MoM in July compared to 0.7% MoM in June) had tempered), which led to market hopes that the Fed would become marginally more dovish.

The Fed has indeed left the option of potentially becoming marginally more dovish open, as it has communicated in the below breadcrumbs:

- Meeting minutes for July meeting: Per minutes of the July FOMC meeting: “Participants judged that, as the stance of monetary policy tightened further, it likely would become appropriate at some point to slow the pace of policy rate increases while assessing the effects of cumulative policy adjustments on economic activity and inflation.” (source: Fed sees interest rate hikes continuing until inflation eases substantially, minutes show)

- Powell: After the July rate hike on July 27, Fed Chairman Powell commented that “As the stance of monetary policy tightens further, it likely will become appropriate to slow the pace of increases while we assess how our cumulative policy adjustments are affecting the economy and inflation.”

However, these tantalizing breadcrumbs have been overwhelmed by the voices of more hawkish members in the past few days, just to give a few examples below based on recent media reports:

- Bullard: “continue to move expeditiously to a level of the policy rate that would put significant downward pressure on inflation” and “I don’t see why you want to drag out interest rate increases into next year”.

- Barkin: been “supportive of front-loading” rate increases. Citing research by former Richmond Fed Research Director Marvin Goodfriend, Barkin said that the policy mistake of the 1970s was the Fed raising and lowering rates in respond to changes in economic conditions even with inflation still too high.

- Daly: “we need to get the rate up, up to neutral at least, which is around 3%, but likely to restrictive territory, a little bit above 3% this year and a little bit more above 3% next year”. “We want to not have this idea that we will have this large hump-shaped rate path where we will ratchet up really rapidly this year and then cut aggressively next year.”

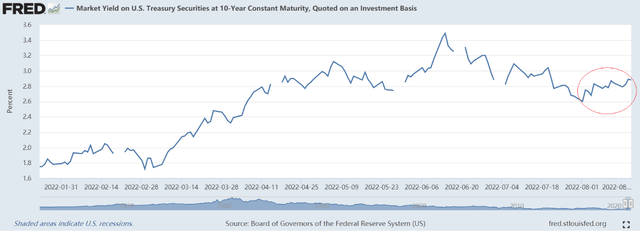

As a result, the 10-year treasury yield has gone from 2.55% on August 2 to near 3% in three weeks’ time, with most of the increase occurring since August 15 (from 2.75-2.8% to 3%).

US 10-year treasury yields (FRED)

From “not even thinking about thinking” to “thinking all the time”: why 2020-2021 may be a good guide of what’s to come

In [June/July] 2020, Powell famously declared that the fed was not even thinking about thinking about raising rates. In fact, even in 2021 he commented multiple times that interest rates were unlikely to be increased for the foreseeable future. Even as late as November 2021, after announcing the start of QE tapering, Powell commented that “we don’t think it is a good time to raise interest rates because we want to see the labor market heal further”.

Fast forward just a few months and this tune was reversed. The Great Ease of 2020-2021 may be helpful for understanding why the Great Hike of 2022-2023 might be more enduring and we are just halfway through:

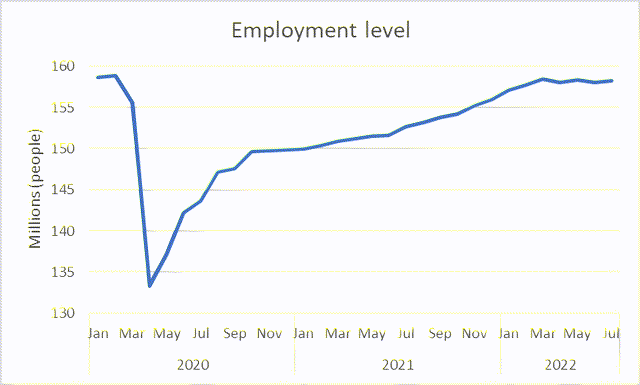

1. A few data points is not enough: If we look back at the monetary easing conducted since March 2020, we could see that the Fed affirmed its support of the economy (and markets) and repeatedly pointed to indicators such as the gap between the number of employed persons then and before the COVID-19 pandemic (which was c. 10 million at its peak as the reasons for staying the course.

As shown below, the employment level was 158 million persons pre-Covid in Jan-2020 and fell to 133 million Apr-2020. By Sep-2020, it had recovered to 150 million. Despite the troubles caused by the COVID variants in 2021, it was clear that the vaccines were having an impact and the labor market trended towards recovery. Yet the Fed chose not to act until Nov-2021 by tapering QE (incidentally this was when the Nasdaq peaked). So it may take a while until the economy flashes recession and inflation is evidently under control until the Fed turns.

Employment level (Bureau of Labor Statistics)

2. The need to maintain consistency: Retrospectively, though the first easing in March 2020 was understandable given the context, leaving the spigots a bit too long may have contributed to the current predicament. However, from a policymaker perspective, it makes sense to err on the side of caution and avoid confusion from policy flipflops which would draw even more criticism from the public. Hence the spigots were left on for too long in 2020-2021 and now the Fed may stay hawkish for longer than expected.

3. Expectation management: this is sort of like the self-fulfilling prophecy:

- If market participants believe that monetary conditions will be accommodative, then they will be more likely to spend and increase aggregate demand and aid the economy to recovery whereas if they are uncertain then they would be less likely to do so.

- Now that reducing inflation requires a decrease in aggregate demand, if market participants believe that a neutral or even restrictive environment is going to end very soon (i.e. a rapid increase in rates now and then a rapid decrease in rates next year), then they may be tempted to increase aggregate demand leading to another increase in inflation. One of the things FOMC members have stated they wanted to avoid is this on-again/off-again attitude towards inflation which caused markets to doubt the central bank’s determination to control inflation which culminated eventually in a much steeper recession in 1980-82 than may have been needed had inflation been crushed in the early 1970s.

Hence it doesn’t seem like the Fed will get dovish until they are certain that the inflation genie is put back in the bottle, which could take some time:

- this means they might overshoot in terms of frontloaded interest rate hikes and keeping the rates higher for a sustained period of time in order for monetary tightening to be credible.

- Other external factors may prolong this: such as inflation from surging natural gas prices in Europe, which are not only high for this winter – the market has priced in even high natural gas prices for winter 2024.

- While eventually rates will go down once a recession starts to become evident (because when have they ever not?), the path could be circuitous and uncertain.

In short, the Fed is clearly telling the markets that the monetary easing they are looking for is nowhere in sight and to buckle up. They are likely to only start reverting to easing once (i) the downward pressure on the economy is evident and (ii) inflation is low for a sustained period of time (i.e. at least several months).

Be the first to comment