Oleg Elkov/iStock via Getty Images

By Bert Colijn, Carsten Brzeski

Government budgets were cautiously tightened for 2022

The war in Ukraine has been another game changer for fiscal policy. First, the pandemic led to unprecedented government support schemes and a more general rethinking of government investment going forward. Now, the war in Ukraine has led to a broad rethinking of European defence spending and yet another push for an even faster green transition and energy independence. Also, we expect more government support schemes in the coming weeks and months to offset the adverse effects from high energy prices for consumers but also corporates. To get a good handle of fiscal policy from here on, it’s important to look at where we were before the watershed moment for European government spending started.

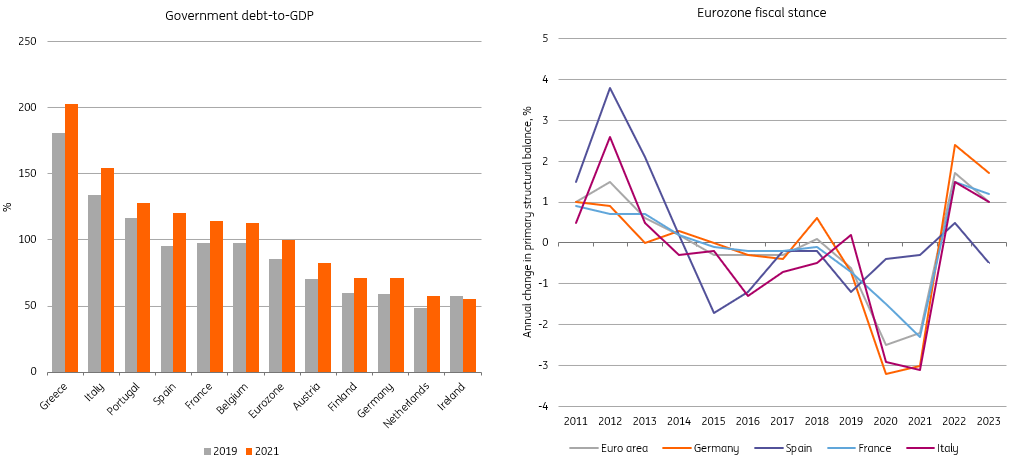

The pandemic has caused debt levels to run up dramatically as the strong fiscal response and sharp GDP declines added to longer-term debt concerns. For 2022, many countries still run budget deficits larger than 3%, keeping policy accommodative. This is in line with the activated general escape clause in the Stability and Growth Pact, which allows countries to not adhere to the 3% rule to stave off the negative economic impact from unexpected adverse economic events, in this case the pandemic.

Governments Were Reducing Budget Deficits As Debt Levels Have Run Up (European Commission AMECO, ING Research)

So, at the national level, governments had started 2022 moving away from very expansionary policy towards normalisation as the pandemic had moved into a less-impactful phase for the economy. The new geopolitical reality is now adding to fiscal spending needs though, likely reversing course for eurozone governments.

The war will change spending through three main channels

We expect fiscal spending to change in three main ways, resulting in more spending for 2022, but more notably also resulting in higher structural spending beyond 2022.

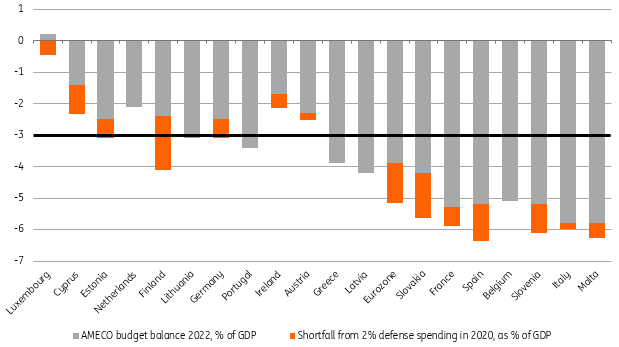

1) Defence spending is set to see a significant revival. Germany led the way when Chancellor Scholz announced a plan including 100 billion euro from the 2022 budget for the military and to reach 2% of GDP in annual defence spending in the years to come. The latter is something that many eurozone countries fall short of, and as most are NATO countries, they are therefore not fulfilling their commitment. The EU summit in Versailles agreed on substantially increased defence expenditure and investment. The chart below shows a rough calculation of what additional defence spending would mean for deficits, taking 2020 military spending data and matching them with 2022 government budgets. It shows that boosting military spending to 2% of GDP would lead eurozone budget deficits on average to surpass 4% of GDP, as it is currently at just 1.5% of GDP; at least when all other expenditures remain unchanged.

Additional Military Spending Would Add To Already Significant Budget Deficits (World Bank, European Commission, ING Research)

2) Energy dependency reduction is set to be a focal point of government policy in the short and medium term. The Commission’s REPowerEU plan is at the heart of this and has drafted the main pillars for government action, which we have addressed in more detail here. Short-term plans include shifts away from energy dependence from Russia, which is hard to achieve without increasing spending. Looking at the medium term, plans for the green transition are now going to be done sooner to help achieve energy independence goals. These plans include sizable investments in renewables, but also investing in gas and electricity infrastructure, among others. It is hard to put numbers on these spending categories, but it will be significant. Think of Europe’s weak bargaining position with new suppliers and the need to increase and speed up investments in times of labour shortages and commodity price inflation.

3) Fiscal support for households is being ramped up to counter the negative purchasing power effects of higher energy prices. This already happened at the end of last year to a modest degree when natural gas prices first spiked, but the current situation is causing governments to add new rounds of stimulus. The impact of this is far more modest than pandemic support, obviously, and is set to remain much smaller also in case of prolonged high energy prices. In case the economic fallout turns out to be larger than currently expected, automatic stabilizers will also cause spending to be up. High energy prices will not only affect households but will also undermine European companies’ competitiveness, up to production disruptions. As a consequence, we wouldn’t exclude eurozone governments to decide on support schemes for companies in the coming months – about which the European Commission has already confirmed that EU state aid rules will not hinder this.

All in all, this means that while fiscal spending for 2020 and 2021 was characterized by extraordinary fiscal stimulus to battle the negative impact on the economy from the pandemic, we are now facing a crisis that is set to result in more spending for the short and medium term on energy dependency and defence. There is some overlap in the EU recovery and resilience facility, through which substantial green transition investments have been agreed. Still, the specific focus on urgent energy independence makes the green transition plans helpful but not enough when looking at EU plans.

Is there room for more spending, or will this come with budget cuts?

As said before, there is limited space to absorb the extra spending without either debt running up, spending cuts, or increased taxation. With debt levels already high and deficits on average still above 3% of GDP in the eurozone, governments have limited space.

The general escape clause from the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) remains in place for 2022, meaning that governments do not need to adhere to the fiscal rules for now. No country will be put in the so-called Excessive Deficit Procedure for running fiscal deficits higher than 3% of GDP, debt ratios of more than 60% of GDP, or for the lack of reducing the debt ratios. For next year, the question is whether the escape clause will still be effective – something which will only be assessed with the next European Commission macro-economic forecasts, to be released in May. At that time, more clarity about the economic impact of the war should help gauge whether the general escape clause should remain in place in 2023.

Additional government spending as a result of the war will now add to the ongoing discussions about changes of the fiscal rules. Advocates for excluding certain spending categories from the fiscal rules, like investments in the green transition, will now also argue for excluding defence spending. However, government representatives from Northern eurozone countries like the Netherlands or Germany have already voiced strong concerns against excluding certain expenditure categories. We think that the more expenditure categories get the label of “highly important” and “should be excluded from fiscal rules”, actually the lower the likelihood of significant changes will be. It would be a strong watering down of the rules and an endless and very cumbersome monitoring and surveillance exercise. Instead, there are, in our view, two possible options going forward: more discretionary power for the European Commission to develop better country-by-country paths combining high investment needs with longer-term fiscal sustainability. The other option would simply be to finance projects of common interests, like defence but also the green transition, with common money.

Joint debt issuance indeed seems to be on the table again. Even if plans for a new EU fund have been dismissed so far by quite a number of countries, the possibility continues to be explored in Brussels. There are lighter options imaginable – think of a SURE-type lending scheme or the use of loans from the existing EU recovery and resilience facility. A full-fledged fund would be favourable for already high debt levels, as debt would be taken on at the EU level to fund additional investments and spending. The latter two joint debt options would still result in more borrowing for countries but at attractive rates, which would make sure that countries would not face higher debt issuance because of this. That would be helpful in times of extra spending at already high debt levels with monetary tightening.

Tough choices ahead

There are no easy choices on the table here. The structural increase in spending is going to come with either running up of already high national debt levels (which would mean a further breach of the SGP and realistically demand more far-reaching reform), austerity on other parts of the government budget, or further steps towards a transfer union. Tough choices generally mean delayed decision-making in the EU, but crises can make the EU make ground-breaking decisions at decent speed – as the corona crisis showed. This crisis has the potential to do something similar, but we do expect this to be in part path-dependent on how the war in Ukraine develops. If it is quickly solved and the economic impact abates, we expect next steps to be less far-reaching. If it escalates further, this could mean more drastic steps towards burden sharing and quicker resolve.

Fiscal policy will remain accommodative in the years ahead, but not splurgingly accommodative. The age of austerity is over, but prudence is not out the door. We expect some rebalancing of government spending to happen, but not actually leading to tightened policy stances in the medium term. And how accommodative fiscal policy can then become depends on whether defence and energy independence spending is funded centrally or not, whether there will be substantial SGP reform, and whether the ECB continues to be an important player in the bond market.

Our best guess at this point is that a SURE-type lending programme will be introduced. This fudge allows governments to structurally invest at low rates. The fact that this does add to national debt continues to force governments to reform and remain prudent in other spending. This still demands significant SGP reform, but with low interest rates locked in, EU leaders can afford to kick the can down the road with that issue for some time to come.

Content Disclaimer

This publication has been prepared by ING solely for information purposes irrespective of a particular user’s means, financial situation or investment objectives. The information does not constitute investment recommendation, and nor is it investment, legal or tax advice or an offer or solicitation to purchase or sell any financial instrument. Read more

Be the first to comment