Max Zolotukhin

I published negatively on Brookfield Business Partners (NYSE:BBU) (NYSE:BBUC) before (“The Siren Song of Brookfield Business Partners“) and for a while, considered the case too obvious to revisit in depth. However, comments by one of my readers changed my mind.

For the rest of this post, I will be talking about Brookfield Business in its BBU form (partnership) but my arguments equally relate to BBUC as well (BBUC is a twin corporation with its share price linked to the BBU unit price).

Brookfield Business Partners’ structure

BBU is a private equity arm of Brookfield Asset Management (NYSE:BAM). It means that BBU acquires (or invests in) companies that are often but not necessarily in trouble, fixes or improves their operations, and, in several years, sells them through IPOs or privately at much higher prices. The companies that BBU pursues belong to various industries from financials to business services to manufacturing. Thus BBU has a broader investment mandate than other Brookfield’s investment arms such as public Brookfield Infrastructure (BIP) (BIPC), Brookfield Renewable (BEP) (BEPC), Brookfield Reinsurance (BAMR), and private Brookfield Property Group that once used to be public (BPY).

BBU is a partnership managed externally by BAM as its Managing General Partner. The management terms are governed by the so-called Master Services Agreement which is a rather long document. Among other things, the document directly states that the Managing General Partner does not have any fiduciary duties or any obligations regarding Limited Partners, i.e. BBU unitholders. In other words, BBU is not run in the interests of its unitholders but exclusively in the interests of BAM. Still, BAM owns about two-thirds of BBU’s limited partners.

BAM’s interests in running BBU can be itemized as follows:

- BBU pays BAM 1.25% of its total capitalization in annual management fees.

- Besides management fees, BAM is entitled to incentive distributions (or performance fees) equal to 20% of an increase in the volume-weighted average unit price of BBU over an established incentive distribution threshold. This threshold is calculated quarterly and is currently $31.53. If at the end of a quarter BBU’s volume-weighted average unit price exceeds this threshold, a new and higher threshold is established similar to the high watermark for hedge funds.

- BBU represents BAM’s capital in private equity funds that BAM raises periodically from third parties. BAM’s policy is to invest alongside its limited partners in private funds (“alignment of interests”) and in this regard, BAM differs favorably from some of its peers. Through public BBU, BAM typically invests close to 25% of capital into private equity funds.

All three items are important for BAM but without much hesitation, I would point to the third one as the most important. Alignment of interests helps BAM to attract outside investors to its private funds. BAM is entitled to receive similar management fees and carry instead of incentive distributions on this external capital. Crucially, the capitalization of private equity funds far exceeds the capitalization of BBU (just for the latest private equity fund, Brookfield seeks $15B in capital vs. ~$4B of BBU and BBUC combined market cap).

For BAM, BBU’s cash is designated (in the order of importance) to accomplish the alignment of interests, pay management fees, and pay performance fees once BBU is lucky enough to exceed its threshold.

What is left for BBU’s limited unitholders? In terms of cash, not much: BBU pays 25 cents in annual distributions (~1% yield) which are not designed to grow. BAM indicates explicitly that limited unitholders are supposed to receive returns via capital gains rather than distributions. At this point, you might wonder why BBU pays out precious cash at all. I guess cash distributions make BBU investable for certain institutional and retail investors that otherwise would not be allowed by their mandate or willing to invest.

Elusive unit appreciation

In its own way, BBU is highly successful. In my opinion, it is managed brilliantly and with amazing creativity. Some of BBU’s feats – such as the Westinghouse transaction or GrafTech’s (EAF) transformation – are second to none. Mistakes have been made (for example, Teekay Offshore, currently Altera Infrastructure) but they have been rare and isolated. From BAM’s standpoint, BBU’s success manifests itself in scaling up its private equity funds (in terms of assets under management) with the related growth in management fees and carry. As a BAM shareholder, I am quite happy.

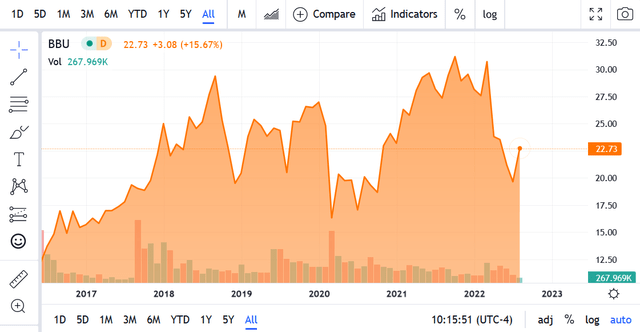

Have limited shareholders beensuccessful? You can judge yourself from the following chart:

BBU unit price (Seeking Alpha)

Upon BBU’s spinoff in 2016, the units were cheap and quickly appreciated. However, there has been no further progress since mid-2018. In my first piece on BBU, I anticipated this and stated the following (I apologize for quoting myself but cannot state it better today):

“… the worst disadvantage for investors is BBU’s incentive distributions or “performance fees” as Brookfield calls them. Other subsidiaries pay them as well but they are tied to stable distributions rather than the fickle stock market. Typically, people invest for two reasons: either to get income (irrelevant for BBU) or to enjoy significant capital growth in return for facing stock market risks. In BBU’s case, the reward/risk balance is highly asymmetric. If BBU is successful its unit price may grow beyond its high watermark threshold. At that time, 20% of the market cap increase IN CASH goes to BAM. Moreover, at the same moment of high unit prices, BBU is likely to issue additional units diluting investors. Sooner or later, the fickle market may go down again but the cash is irrevocably gone… So, BAM enjoys the benefits of market fluctuations at the expense of retail investors.”

Some investors may think that since BAM owns two-thirds of BBU, limited unitholders’ interests are aligned with BAM’s. In a way this is correct: provided everything else is equal, BAM is interested in higher unit prices (sometimes, BBU even repurchases its units). But this is only when everything else is equal! As we have seen this is not necessarily the case as BAM has other priorities.

Why does BAM need BBU at all? Without public BBU, BAM would have to provide an alignment of interests for big institutional investors using only its own capital. With BBU, BAM can use other people’s money for the same purpose and milk this money at the same time by charging fees. Again: as a BAM shareholder, I can only admire the efficiency of these operations!

My reader (who triggered writing this post) knows Brookfield’s business quite well. He knows that BAM’s business is driven by fees and understands what incentive distributions are about. Let me quote his comments on my opinion regarding BBU from one of my recent posts:

I also disagree that BBU is not suitable for long-term holdings because of the incentive structure. All of the subs BIP, BEP, BBU pay incentives to BAM but are still able to deliver outsized returns to unit holders even after paying those fees. BIP and BEP pay them based on FFO, and BBU pays them based on unit price. If anything, an incentive based on unit price is more closely aligned with outside investors who own the units. BBU has produced 15-18% returns on NAV every year since inception even after these distributions, though the unit price has languished. At around 2/3 of NAV, it is by far the cheapest of all BAM subs.

In 2021 BBU paid incentive distributions of $157M in a year when they earned about $1.7 billion in cash flow from operations. Their investments are all cash flow positive and they cover their distributions to BAM and to their own unit holders many, many times over. Not sure why you think these fees are “enormous” or somehow make it unworthy of investment. The unit price could double and they’d easily cover these distributions 10 times over from their own cash flows.

Please note that trading in BBU units can be successful – I do not deny it. For example, with units currently at ~$22 and the threshold at $31.53, there is plenty of room for appreciation. It is no more than my personal preference to avoid trading. I keep referring to one of Buffett’s rules: if you do not feel comfortable owning a stock for 10 years, you should not own it for 10 minutes. In this regard, BBU hardly fits the bill.

My reader mentions impressive BBU’s cash flows and implies that BBU’s cash belongs to him as a limited shareholder in the same way that the cash Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A) (BRK.B) earns belongs to a BRK shareholder. I disagree but let us assume he is right. Then 20% of the market cap increase in incentive distributions due to BAM upon exceeding the threshold is equivalent to a limited partner writing a call option with an exercise price equal to this threshold. But this is a truly bizarre call.

First, limited partners write this call for free – BAM does not pay them a premium. Secondly, this option has no expiration date. And thirdly, once BAM exercises this call, unitholders immediately write a new call for free with a new strike price equal to the new threshold.

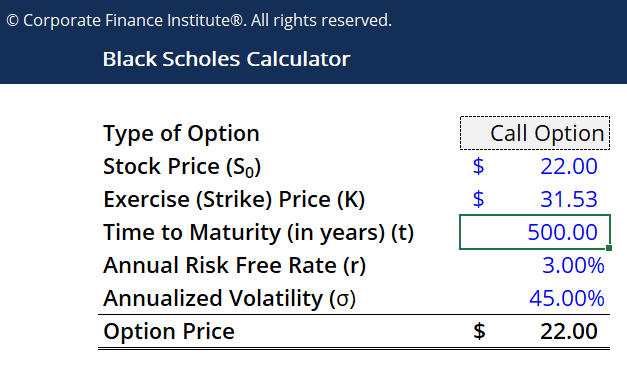

The current strike price is $31.53. How much is this bizarre call option worth? The right to buy a unit for $31.53 in the future without any time limitation is worth exactly today’s stock price or ~$22. It seems straightforward to me since the stock with meager dividends and the option that never expires provide the same benefits of a possible capital gain. However, those who doubt it can use the Black-Scholes formula to check:

Author

Since BAM receives only 20% of the BBU market price increase, every investor buying a unit is sacrificing 22*20% = $4.40 of the fair call premium. It can be crudely compared to buying a mutual fund with a 20% load or buying a stock with a 20% brokerage commission. Combined with meager cash distributions, it does not seem enticing to me regardless of the figures in BBU’s financial statements.

By the way, whatever we said about BBU is not fully applicable to BIP or BEP primarily because they both pay out rich and annually growing distributions. For BIP and BEP investors, cash is not so elusive. Secondly, both BIP and BEP are much bigger than BBU, and BAM makes much bigger fees from their capitalizations. If they trade materially lower, it may even affect BAM’s share price.

Conclusion

Some BBU diehards may object: “But maybe BBU makes so much cash that it justifies a 20% entry ticket?” Maybe. But I would look for better options.

Be the first to comment