Maria Vonotna/iStock via Getty Images

Investment thesis: The current decade is proving to be one of some dramatic global changes, of historical proportions. The increasingly interconnected world is starting to unravel and we are breaking into two separate camps. One camp centers around the US and another around China. There is also an unaligned group in the middle, with most neutral countries arguably seeing their own interests more aligned with the BRICS-centered group. Our aggressive tactics of pushing extraterritorial sanctions on their bilateral dealings with the other camp seem to increasingly annoy the neutral nations. Furthermore, the great economic decoupling seems to be inflicting a great deal of economic pain on some US allies, with their economies shrinking precipitously this year in USD terms, even as the likes of Russia & Iran are seeing the size of their economies in nominal USD terms gaining ground. In light of this profound change in the global economic and geopolitical order, investors should consider pricing a great deal more risk into every investment decision. This decade might turn into a challenge to maintain real wealth for most portfolio strategies, rather than being an opportunity to gain.

The great global economic war arguably started with the proxy war in Ukraine.

We have been sliding towards this moment for some years now, but it all arguably came to a head with Russia’s decision to invade Ukraine this year. Much of the Western World, together with a handful of other allies mobilized itself for a proxy military confrontation on the ground in Ukraine, as well as an economic war on Russia, which is being waged globally, affecting most other nations on the planet. Russia seemingly has few open allies, but there seems to be quite a bit of tacit support coming from much of the rest of the world, with most countries outside of the Western alliance completely uninterested and even annoyed with the current economic war being waged by the West against Russia.

Separately, a tech containment war started against China some years ago. The takedown of Huawei was arguably the starting point of that conflict, which kept escalating over the past years, and it has intensified over the last few months, with the latest semiconductor-related sanctions on China being arguably paralyzing on a sectoral basis. It remains to be seen to what extent China can re-adapt its tech sector in order to help it cope.

The unilateral withdrawal of the Trump administration from the Iran nuclear deal led to what is today another major global economy being heavily sanctioned. These three countries are faced with increasing isolation from the Western Block, therefore it is inevitable for them to merge into an opposing economic and geopolitical grouping, with many other nations, such as the ones in Central Asia inevitably becoming allies due to geographical realities.

Ever since the emergence of the Western-dominated post-WW2 World order, there have been many nations that faced similar sanctions. It should be noted however that these three countries currently make up over 20% of the world’s total GDP, based on the IMF’s latest numbers. Nor can this be compared with the Soviet-NATO face-off, mostly because the Soviets were running a deeply flawed socio-economic experiment that was always pre-destined to implode. Furthermore, China is the world’s factory, meaning that it cannot be fully or even partially contained on the global stage, given that the whole world depends on manufactured products and intermediary goods that it provides. Russia is also indispensable on the global stage, given that it is the world’s largest net exporter of commodities. Within the context of what seems to be a decade of tight supply-demand balances in many commodities around the world for the foreseeable future, it provides Russia with outsized leverage over the global economy.

Year one of the great economic war can be summed up as one where it seems to pay more to be a US adversary than an ally.

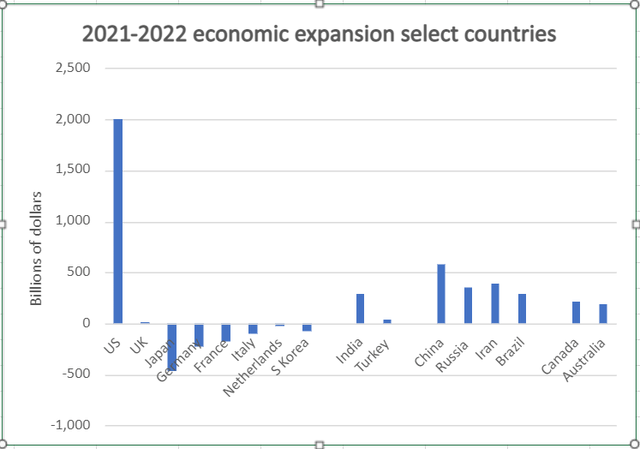

As we can see, the US is doing comparatively well in relation to much of the rest of the world. It even managed to outgrow its main global rival China by a wide margin, making it less likely that China will become the world’s largest economy in nominal terms any time soon. Its main geopolitical and economic allies around the world, however, have been seeing a less-than-stellar performance this year. The group of countries I highlighted in the chart collectively as being together with the US, lost about $1 trillion dollars in terms of the size of their collective economies this year compared with last year. When we add the rest of the EU as well as a number of other allies around the world, it rises to about $1.2 trillion

Interestingly, the two most sanctioned nations, among all major global economies, namely Russia & Iran have seen some impressive gains in terms of the size of their economies in nominal USD terms. China is still suffering from its COVID-Zero policies, as well as from an intensification of sanctions on its economy, especially in the tech sector. India & Turkey, arguably neutral nations are seeing decent economic growth rates, with Turkey, in particular, suffering from a case of currency devaluation, which is stifling its economic expansion. It is, however, methodically and systematically creating new global economic connections, mostly with the BRICS group, which could bear fruit in coming years, especially if its currency devaluation situation will be brought under control.

There are two main factors that shaped the nominal growth pattern of certain nations this year. Arguably the most important factor has been the volatile currency exchange rates, with the US dollar doing particularly well. The ruble is outperforming the dollar this year, which explains its spectacular gains in nominal USD terms. The euro and other currencies have been having a hard time, which is reflected in some economies shrinking a great deal this year in USD terms. The other factor has been the global commodities market, which to some degree affected the global FX market in favor of major net exporters of commodities. In the particular case of China, the Zero-COVID policy is perhaps the main factor that is curtailing its growth, which is a separate issue from the two above-mentioned issues.

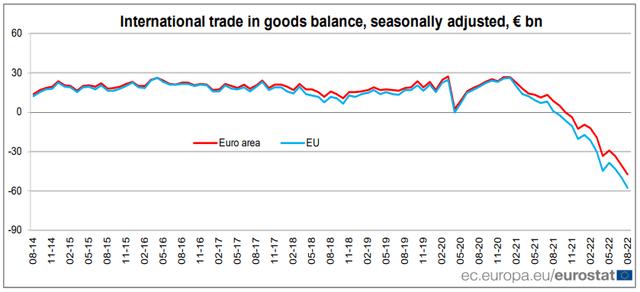

One might be tempted to argue that since currency exchange rates are the main culprit behind the shift in the global economic weight, there is not much to it in terms of permanence. This is a flawed assumption. The EU for instance is faced with a growing trade deficit gap, even as the euro keeps weakening, which is not what one might expect according to economics 101.

One of the main factors that contributed to the end of Europe’s steady run of trade surplusses has been the spike in energy prices. Those pressures will probably persist and even worsen if the euro keeps losing ground on the global FX market. There will also be secondary effects, with more and more industrial activities ceasing, which will lead to fewer exports, despite the weaker euro, which should ordinarily make EU exports cheaper and more attractive. A shrinking industrial base will also hit Europe’s overall economic activities. As things stand right now, Europe’s fertilizer production is cratering. Aluminum production is also down significantly. The very important EU auto industry is forecast to shrink as much as 40% if the crisis continues.

Looking at Europe’s fundamental economic trends, there seems to be no basis to expect a firming of the euro currency going forward. The ECB is caught between surging inflation and a cratering economy. Even as the EU economy shrinks in USD terms, so does its real economic output. It is a bit of a distortion that still has it growing in euro terms, even as more and more industrial establishments are shutting down. For this reason, there is no prospect for a currency rebound, therefore the shrinkage in its economy is real, tangible and it is long-lasting. Worst of all, as long as the economic confrontation will last, so will the trend of further economic shrinkage.

America’s main allies are exposed and vulnerable due to an acute lack of critical natural resources.

The main differentiating factor in the way the US economy fared through the opening salvoes of the global economic war versus its main allies is the degree of self-sufficiency in terms of natural resources. I left out two of America’s main allies to the right side of the economic expansion chart, on their own, mostly because I wanted to highlight the difference that let them expand more akin to what we have seen this year with the US, or Russia & Iran. That all-important factor is of course the level of commodities self-sufficiency that countries like Canada & Australia enjoy, versus the relative poverty in this regard that a country like Japan has to cope with. Both countries enjoyed a proportionally similar increase in the size of their economies this year compared with last year as the US did.

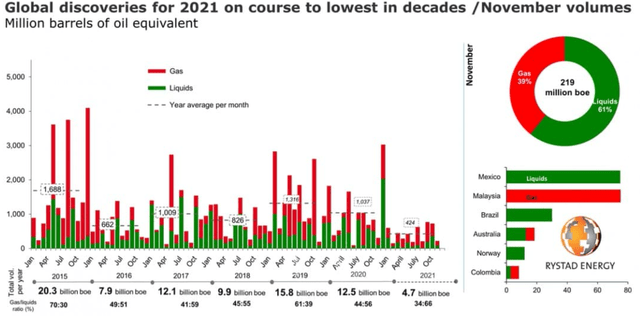

The China-centered block that is emerging, shaped by the degree to which certain countries are facing sanctions, tends to be rich in critical natural resources that the world is deeply dependent on. Russia for instance is the world’s largest net exporter of commodities. Oil, gas, food as well as certain metals, nuclear fuel, and fertilizers are all raw materials or processed raw materials that the world cannot easily replace, especially not on short notice. Some of these materials, especially oil & gas, the world cannot replace, even if we are given the time.

Last year the world discovered just about 5 billion barrels of oil equivalent in oil & gas combined, even as we produced and consumed about 45 billion barrels of oil equivalent. Other countries like Iran or Brazil are also well-endowed in this regard, and Saudi Arabia has been cited as a future potential BRICS member. Time is clearly not on our side in terms of replacing Russian oil & gas supplies. The only thing that can help is demand destruction, and as we are curtailing some of these Russian products from making it to market, we see more and more that the EU and Japan are the main candidates for the necessary demand destruction that needs to take place in order to rebalance the global supply/demand situation.

The US has a very hard decision to make. It sees the economic confrontation with Russia, Iran, and increasingly with China to be of vital economic and security interest. Its economy is well enough insulated from overdependence on primary economic inputs that it can comfortably take the fight to its adversaries. At the same time, its main allies around the world are not in a position to withstand the blow of losing access to certain resources as well as some goods.

In order to continue this confrontation, especially with Russia, it needs to share resources. In other words, accept a certain level of demand destruction in its own domestic economy in order to help Europe and other allies out.

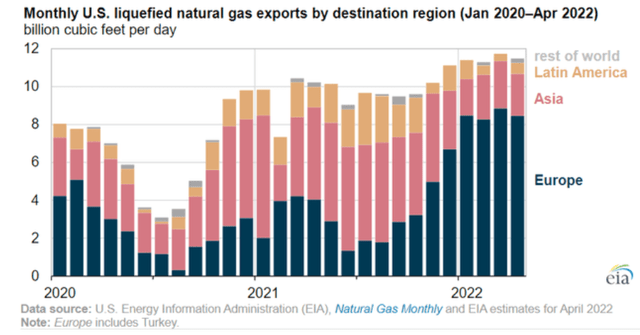

On the issue of natural gas shortages in Europe, the US is already doing a great deal. It diverted massive volumes of LNG to the European markets and increased overall export volumes. The measure is set to have a significant impact on US utility costs this winter. More will have to be done next year, on natural gas, diesel, and other fronts, if the policy of economic confrontation is to continue going forward. There are only two alternatives. One is to continue with the economic confrontation and risk the outright implosion of the EU, the UK, and Japan’s economies. The other choice is to de-escalate and have some sort of rapprochement.

Potential fallout:

There are currently no signs that the path to de-escalation is at all a viable outcome, therefore we have to assume that the global economic conflict will continue. What this means is that the US, UK, EU, and Japan will all have to accept further declines in energy usage. The EU ban on Russian oil & diesel will come into force in December and February, respectively. As a result, US diesel exports will probably have to increase significantly in the coming months, which will cause a further spike in overall inflation, given that diesel is critical in the transport of most consumer and industrial goods. Higher inflationary pressures will in turn lead to more aggressive monetary policy tightening, which will last far beyond the expected levels of economic pain that will be inflicted as a result. In other words, the level of demand destruction will have to be deeper than most might expect before there will be a much-expected Fed pivot. As a result, the recent stock market bullishness should not be seen as a sign of bottoming. There are still some months to go, at least. In my view, the earliest that we can expect that pivot will be late spring, next year.

Even though the US is likely to try to aid its energy-poor allies in surviving the intensifying global economic confrontation, it may not be enough. This may be the case especially since it seems that ME and other net energy exporters that could help seem to be at most disinterested. OPEC as well as Qatar have been warning throughout this year that there is no replacement for the massive volumes of energy that Russia is exporting. Even if there were to be more that they could do, it seems that they are not at all interested in yielding the Asian market to Russia and pivoting to the aid of the EU market, which is increasingly seen as a long-term loser from the perspective of commodities exporters.

Next year, the EU and UK energy situation could become untenable, even with enhanced US exports to the region. Given that the political leadership invested itself into the justification for the conflict, it will be very hard to pivot away, therefore we may be looking at an economic meltdown event for the EU, which is the 3’rd largest global economy, and the UK which is the world’s 5’th largest. In other words, it would be politically tough for them to pivot, even if at this point they see the economic danger. It is hard to formulate a positive investment story for next year within that potential context.

We should also keep in mind that while we keep ratcheting up pressure on China’s tech industry, trying to deprive them of technologies needed to advance, China is yet to seriously retaliate. We don’t know whether they ever will, or when they will do it, nor in what form they will do it. Or perhaps they are already retaliating, and we just don’t realize it yet. My personal view is that the more vulnerable we become, as the current economic war is wearing us and our allies down, the more likely it will be that China will retaliate, especially since we are gradually removing all incentives for China to try to preserve relations. My view on this is that China may act next year, especially if the economic situation in the EU and to a lesser extent in the US becomes direr. There is no telling how intense any potential Chinese economic or geostrategic measures might be, but for now, we have to be aware that the risk is there and it is probably intensifying in terms of odds, as well as in terms of the potential magnitude of impact.

Investment implications:

Risk is something that needs to be re-priced for most portfolio positions, given the overall global economic outlook, within the context of what now seems to be an inevitable slide into a period of deglobalization. At the minimum, we need to increasingly assume that multinational companies will have a harder time penetrating certain major global markets, while also potentially facing rising competition in non-aligned markets, such as India for instance. In a worst-case situation, we will be faced with a situation where opposing economic & geopolitical blocks will continue to seek to destroy each other economically, with escalating measures, leading to more escalation and a never-ending vicious cycle of resulting wealth destruction. In this hypothetical worst-case situation, the global business environment as well as local markets are set to see a marked deterioration. Living standards are likely to plunge, and with that so will the global investment environment.

My personal response to the situation has been to shift to a more diverse portfolio, with my overall objective being to avoid building a position that exceeds 3% of my overall portfolio in any particular stock or ETF. I still have some legacy positions that far exceed that, such as Suncor (SU), which I am in no rush to reduce, given my expectations for a continuing commodities bull market, even as we are increasingly seeing demand destruction take hold. A few new positions also exceed that mark of roughly 3%, but not by much.

When investing in new positions, I am looking for deeply discounted assets that I deem to be an otherwise solid long-term investment opportunity. For instance, I recently bought Intel (INTC) and AMD (AMD) stocks in small increments. If such oversold opportunities do not present themselves, I prefer to stay in cash, which now makes up well over 30% of my overall portfolio. Gold also needs to be a prominent part of a portfolio now more than ever in case the entire fiat financial system goes for a dive, which is no longer a scenario that we can deem as far-fetched. My physical gold & silver position, as well as my position in GLD (GLD) as well as Barrick Gold (GOLD), as well as Wheaton (WPM) stock, amounts to about a fifth of my current total portfolio.

I see gold as an insurance policy in the event that things go South, although it should not be assumed that it is guaranteed to work. No position, be it in stocks, bonds, currencies, or gold should be seen as safe at this point. It may be the case however that some assets will prove to remain valuable throughout this decade of turbulence. And at some point, when things will settle down, perhaps with a new global grand bargain emerging that will allow the different warring factions to coexist and even cooperate in the interest of mutual benefits, one has to be ready to take advantage of new opportunities, which of course requires capital. For now, however, this is less a time of opportunities but rather one of having to fight for real wealth preservation. It is bleak to even contemplate it from an investor’s perspective, but it is also necessary to actively look for strategies to preserve as much as possible, and wait it out, while we cross into what will hopefully be a more stable and prosperous future.

Be the first to comment