Thomas Barwick

Introduction

I published an article about Cresud (NASDAQ:CRESY) over a year ago with a ‘buy’ rating at a price of USD 6.3 per ADR. The stock later peaked at almost USD 9.7 per ADR (+54% since publication) and now is down -50% from that peak, trading at USD 4.6 per ADR, an even lower price than when I published that article. I see this as a new opportunity to start a long position if you haven’t already, and so a great time for an update on that previous article.

Cresud’s stock behaviour (Seeking Alpha)

Although I will be conducting some valuation-related calculations, I assume most of you know how to approach this task – and probably even better than me in fact. So I decided to spend most of the time instead talking about those ‘Argentine particularities’ that you probably are not familiar with but should definitely know before investing in this stock, i.e., capital controls, central bank’s regulations, different FX rates and how to interpret them, etc. For this, keep in mind I’m an Argentinian investor living in the country, and I’m therefore certainly familiar with this ‘particularities’, so feel free to ask me any doubt you may have down in the comments.

Market Capitalization

I like to start my articles by giving a look at the company’s Market Capitalization and Enterprise Value (EV), for obvious reasons. It’s the price we would be paying for buying the company. It makes no sense to discuss anything else if we don’t know first the price the market is asking us for to buy whatever assets and business the company possesses. So let’s recap this, and make sure we have the correct numbers in mind. If you’ve been following my articles on the Argentine market, you already know it’s easy to get this wrong, so stick with me.

Cresud’s capital stock is comprised of 591 million shares. This shares trade at Bolsas y Mercados Argentinos (ByMA), a conglomeration of Argentina’s stock markets.

Each American Depository Receipt (ADR) trading at NASDAQ under the ticker CRESY represents 10 shares. Therefore, Cresud’s capital stock is equivalently represented by 59.1 million ADRs.

At the time of writing this article, each ADR trades at about USD 4.6. So Cresud’s market cap is USD 271 million.

If you search for Cresud’s market cap in most investor’s online services a different number will pop up. This is because these platforms are either outdated (Cresud went through a capital increase last year and some platforms still use the old capital stock) or just do the math plainly wrong. Or sometimes is a combination of both.

How can be the math wrong? Well, what these platforms usually do is take the 591 million outstanding shares, multiply that by the stock price in ByMA (ARS 154 per share) and divide that by the official FX rate of ARS 135 per USD. It’s this last step that’s wrong. Due to strict capital controls currently in place in Argentina, the official FX rate differs significantly from the market’s FX rate, ARS 330 per USD at the time. This ‘free market’ rate is commonly referred locally as ‘Contado con Liqui’, or CCL for short.

How is this CCL obtained? Well, simply by taking a look at the Cresud’s price at NASDAQ and ByMA and doing the math, like this:

10 shares = 1 ADRs, with each share trading at ARS 154 and each ADR at USD 4.6.

Replacing, you get that

10 * ARS 154 = 1 * USD 4.6, or

1 USD = 330 ARS

So let’s get this straight: if you’re a foreign investor (which I assume you are) and you have USD 271 million, you theoretically can buy 100% of Cresud, i.e., you can buy the 59.1 million ADS at USD 4.6 each. So this is Cresud’s market cap.

If CCL goes up, all else equal, you still need USD 271 million to buy out Cresud: nothing changes for a foreign investor in this case. On the other hand, a worker in Argentina will need more ARS to do the same thing, and since his or her income is more or less fixed in ARS terms… well, it will be harder for he or she to buy out Cresud. If fact, if we want to be more precise, if CCL goes up, Cresud’s market cap in CCL terms will very likely go down (stock prices goes down). This is because some of Cresud’s income is in ARS just like an Argentine worker’s is, so when measured in USD at CCL, Cresud profits are indeed less. This is exactly what happened the last months: CCL went up from 200 to 330, while stock went down from USD 9 to 5. This is no coincidence.

So here’s what you need to take from this section:

1. Cresud’s market cap is USD 271 million (@ USD 4.6 per ADR)

2. There are strict capital controls in place in Argentina. This creates at least two legal FX rates: ‘official’ and ‘CCL’, with a 140% ‘gap’ in between them.

Stock Warrants

In addition to the 591 million shares (59.1 ADRs), Cresud has issued 90 million warrants that entitle their holders through their exercise to acquire 1 additional share each at a fixed price of USD 0.566 per share. Therefore, when exercised, there will be 90 million new shares issued, taking the capital stock up to 681 million shares, and USD 51 million will be injected into the company. This should happen by 2026, when the stock options mature (I assume with confidence they will be well in the money by then).

How should we deal with this in our analysis? Well, there are different approaches that are more or less correct. The one I propose is this one: let’s consider there are already 681 million shares issued and that Cresud has a credit of USD 51 million due in 2026.

With this in mind, Cresud’s ‘adjusted’ or ‘fully diluted’ market cap is then USD 313 million.

If you don’t agree with this approach, that’s fine. Stick to the former market cap, but bear in mind that the stock options are out there.

Debt and Enterprise Value

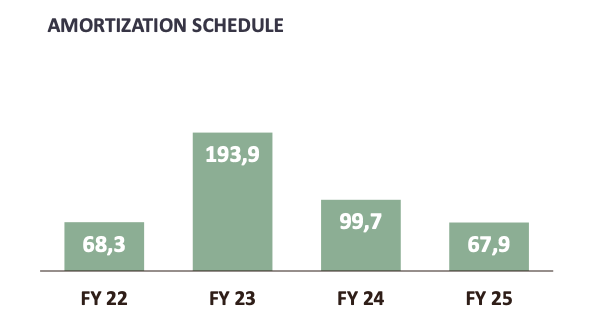

Cresud’s net debt according to the last information available is USD 422 million. Here’s the amortization schedule.

Cresud’s debt amortization schedule (Company’s presentation)

As you can see, maturities are pretty much well distributed over time. This is always a plus that we appreciate very much in a market such as Argentina’s, where access to financing is frequently limited. Having debt maturities spread over time gives you much more time and flexibility to deal with them when you can’t access new financing.

Now, if we consider the USD 51 million in ‘credit’ due to the exercise of stock options, then this net debt drops to USD 371 million. In addition to this, Cresud collected a dividend from its subsidiary ‘BrasilAgro’ (LND) of USD 16 million after this amortization schedule was published. That brings net debt down to USD 355 million.

But this calculation is actually not entirely correct, and here’s where many of you will probably disagree with me (if you haven’t already). But then again, that’s fine. You can adjust this calculations the way you feel comfortable with. But hear me out first:

This debt is mostly USD-denominated, but the company can actually pay it with ARS accessing the official FX rate. That’s a key point. Because we are taking all our numbers in USD at the CCL rate, we can’t just add up the market cap to this net debt to get the Enterprise Value as if they were equivalents, nor the net debt with the proceeds from stock options or dividends collected, because they are expressed in ‘different’ dollars. They are not equivalent.

What do I mean with this? Well, let’s say that stock options are exercised and therefore USD 51 million are injected into the company. That’s 51 million of hard cash US dollars that enter the company, or its equivalent in ARS at CCL exchange rate (this is established in the stock options’ prospect). But since debt is paid at the official FX rate, then those USD 51 million could potentially be used in reality to cancel about USD 125 million in debt.

With this in mind, I could argue that if we want to calculate the Enterprise Value, we should add the market cap with the net debt but this last one adjusted by the CCL rate. We need USD 171 million to cancel the USD 422 million of debt at the official FX rate, so that’s the net debt we should use for our calculation. In addition to this, we have proceeds of USD 51 million from the exercise of warrants plus USD 16 million already collected from dividends. So we are USD 104 million short to be able to cancel all debt. That’s the ‘adjusted’ net debt we should be using in our calculations here.

If you didn’t follow, please stop here and read this section again.

Therefore, EV would be USD 417 million (313 + 104).

So again same idea: if a foreign investor comes with USD 417 million, he or she could theoretically buy 100% stake in Cresud and cancel all debt (That’s the essence of an EV calculation). He or she would buy the 68.1 million ADRs, inject the remaining USD 104 million into the company, sell those USD among the 51 million proceeds from the exercise of warrants and the 16 million of dividends from BrasilAgro legally at the CCL rate (because yes, this is entirely legal), then use that cash to buy USD 422 million at the official FX rate and cancel all debt.

But… this is not entirely correct either! I mean, it would be if the company could freely access the official FX rate to cancel debt as pleased, but it can’t. If it could… well probably there wouldn’t be a 140% gap between the two rates in the first place. Let’s take a look at this.

Communication ‘A7106’

Back in 2020, Argentina’s Central Bank (BCRA) issued resolution A7106 that is still in place today. This resolution limits the access to the official FX rate for companies. In essence, companies must refinance at least 60% of debt maturities at a minimum average term of two years, and are allowed to access the official FX rate for the remaining 40% of the debt maturing.

In case companies want to start an early refinancing process under the guidelines established by the BCRA, the refinancing requirement is increased to at least 70%.

You can read more about this in the BCRA’s official website.

Back to Debt and Enterprise Value

So how should we treat Cresud’s net debt with this resolution in mind?

Well, first let’s establish this:

If we take the net debt to be USD 355 million (USD 422 million of current net debt – 16 million of collected dividends – 51 million from stock warrants), that would be a worst-case scenario, meaning we are considering that company can’t access the official FX rate at all at any time to cancel debt. On the other hand, taking net debt to be USD 104 million would be a far too-optimist approach since we know that the company is unable to access the official FX at will and that debt will never be cancelled entirely at this rate.

Therefore, a ‘fair’ number lies in between this two extreme cases. Cresud should be able to cancel some of its debt at the official FX rate, but certainly not all of it.

If you’re too optimistic you might be thinking ‘well, but it could eventually cancel all debt at the official FX rate, at least in theory… I mean, company may keep refinancing 60% of its maturities and cancelling 40%, until virtually no debt at all remains’. That would be true indeed if these regulations and differences between FX rate extend over long periods of time. But that simply won’t happen. Either the official FX rate will experience a strong devaluation (I consider this to be a very probable scenario in the short term), or capital controls will be lifted after next year’s presidential elections (depending on who wins), or any other variable will change sooner than later, making this scenario very unlikely.

What I propose here is taking a rather conservative approach. Let’s assume Cresud can’t cancel any of its debt at the official exchange rate, except for that debt that matures rather soon and we can forecast with almost certainty that it will be refinanced under ‘A7106’, meaning 30/40% of that maturity will be paid at the official rate.

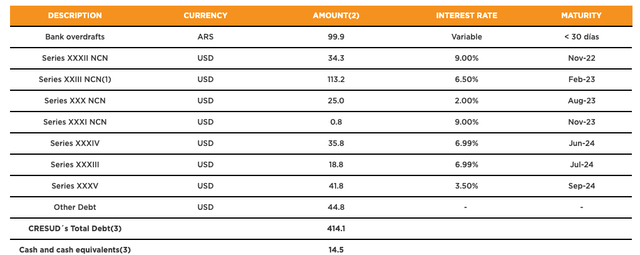

The following table contain a breakdown of company’s indebtedness as of 12-31-2021 (might be a little outdated, but that’s ok for our purposes).

Cresud’s debt breakdown (Company’s website)

You can see in the chart above there’s this USD 113 million corporate bond maturing in February 2023. Based on some comments during the last conference call for IIIQ 2022 (see here @ 20:30), we might assume this maturity will be refinanced in advanced under ‘A7106’. This would be similar to what IRSA did just a few weeks ago, when it refinanced a USD 300 million debt maturity in advanced, by paying 30% in cash and 70% in new longer bonds.

If this is the case, BCRA’s resolution would grant Cresud access to the official FX rate for an amount of 30% of the maturity, so USD 34 million.

Now with all this in mind, and summing up, we can then assume the net debt to be:

USD 422 million as of IIIQ 2022 minus 51 million from exercising of stock warrants minus 16 million in dividends collected from BrasilAgro minus 20 million (you are using USD 14 million to cancel 34 million at the official FX rate, that’s USD 20 million less debt to be considered).

Finally, we assert that Cresud’s net debt can be considered to be USD 335 million.

Therefore, EV is USD 648 million (USD 313 million of ‘fully diluted’ market cap + USD 335 million of net debt).

The More Debt You Can Cancel, The Better

If you’ve followed close this reasoning, then you probably already see that the more debt you can cancel now, the better. Let’s see why.

Normally, there’s an optimal level of leverage for a company. This has to do with many factors, including but not limited to the profits of such company. It also has to do with tax shield, ‘a reduction in income taxes that results from taking an allowable deduction from taxable income’ (see here for more on this). Bottom line is that you want to have a certain level of debt.

But the way I see it, Argentina is offering now an opportunity to reduce that debt ‘cheaply’, even below those desirable levels, using few ARS. This way, you have room in the future to issue new USD-denominated bonds when the debt market reopens and receive hard USD instead.

You don’t see it yet? The net effect of doing this (i.e. reducing debt now using ARS and then issuing USD-denominated bonds for that same amount in the future) is that you’re being able to buy USD at the official exchange rate and use it at will.

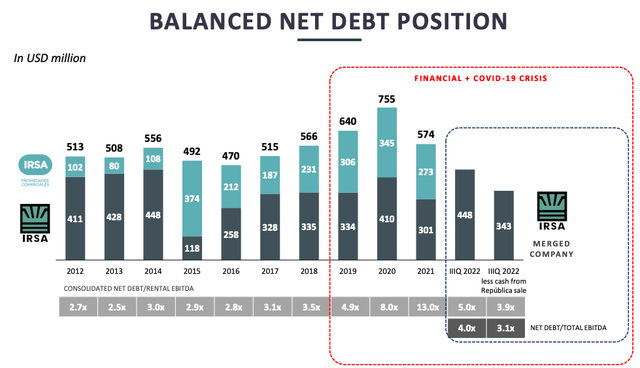

I think that’s exactly what IRSA (Cresud’s subsidiary) has been doing lately. Take a look at this graph below.

IRSA’s historic net debt (Company’s presentation)

The average net debt for IRSA + IRCP has historically been around USD 500 million with a peak of USD 755 million in 2020. However, IRSA has brought debt down recently to below USD 350 million, lowest level in at least a decade. This way, somewhere down the road, there’s room for allocating new USD denominated debt, and hard cash US dollars will flow into the company.

This should not be understated. Think about it: say IRSA decides to increase debt to its historically average of USD 500 million. It can potentially issue a USD 160 million bond and that’s 160 million of cash flowing into the company. That’s almost 60% of today’s entire market cap!

I think Cresud should follow the same path if able.

Company Overview

Now that we know how much we must pay for this company, let’s take a look at what we are getting for that money.

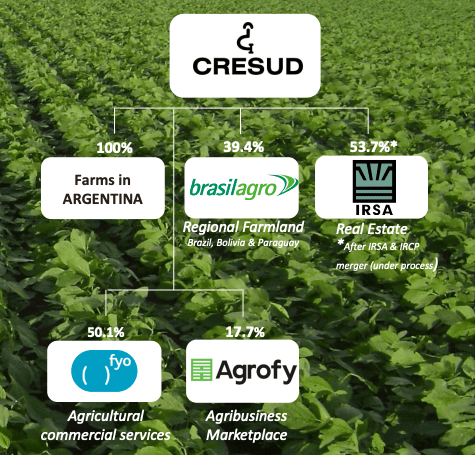

Here’s a view at Cresud’s corporate structure. It’s a very simple and clean structure.

About Cresud (Company’s presentation)

Cresud is an Argentine company, leader in the agribusiness for more than 80 years. It produces high quality goods, adding value to the Argentine agricultural production chain, with a growing presence in the region through investments in Brazil, Paraguay, and Bolivia. These investments outside Argentina are all conducted through BrasilAgro.

Cresud owns directly 536,000 hectares (1.3 million acres) in Argentina, and a 39.4% stake in BrasilAgro which owns in turn about 225,000 hectares (556,000 acres) mainly in Brazil.

In addition to this, Cresud participates in the real estate business in Argentina through its subsidiary IRSA (IRS), one of the leading real estate companies in the country.

Cresud also owns a 50.1% stake in FyO, a leader in agricultural commercial services, and a 17.7% stake in Agrofy, a pioneer in agricultural e-commerce.

If you want to hear about the history of the company, how it came to be and founder’s vision, I suggest you watch this interview with Alejandro Elsztain, CEO of Cresud. If needed, you can turn on automatic captions in English (not perfect, but it can be understood).

Let’s examine Cresud’s businesses individually.

Agriculture

Cresud’s business model is twofold: it produces oilseed and cereal grains, sugar cane and meat and export globally from its almost 880,000 hectares (106,000 leased), while at the same time is active buying and developing lands to sell them later at a higher price, and repeat the process (real estate model).

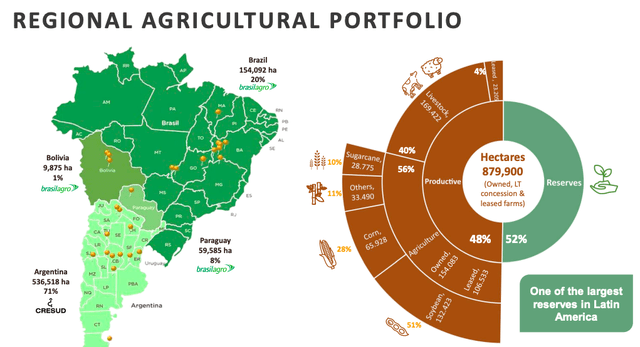

Here’s a glance at Cresud’s regional agricultural portfolio.

Cresud’s regional portfolio (Company’s presentation)

Notice that Cresud has over 400,000 hectares as still undeveloped land reserves.

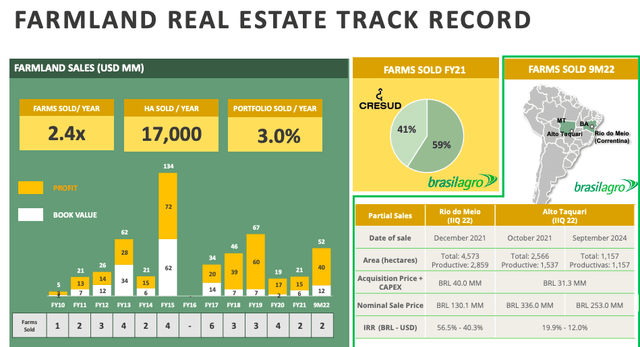

And here’s a look at its farmland real estate track record.

Cresud’s agri real este track record (Company’s presentation)

Cresud sells an avg. of 17,000 hectares per year, profiting an avg. of USD 30 million a year with this transactions.

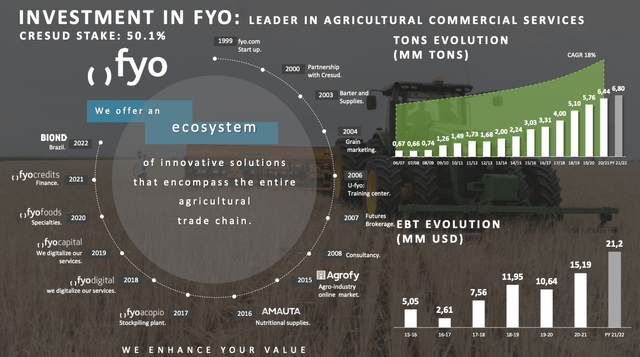

Futuros y Opciones (FyO)

Futuros y Opciones (‘Futures and Options’ in English) or FyO for short is the largest agricultural commercial service of Argentina. It offers an entire ecosystem of services encompassing the entire agricultural trade chain that allows capturing greater value in the commercialization of grains, based on the commercial, financial, tax, logistic and geographic position of each client. These services include not only commercialization of grains, but also financing, hedging strategies, training and advising, among others.

It’s projected that more than 7 million tons of grains will be commercialized through FyO this year. That’s 10x Cresud’s production.

EBIT will surpass USD 21 million this year and is expected to continue growing. The company is now expanding its brokerage business to Brazil and will soon be offering its services in other countries of the region as well.

FyO had no debt until last year when it raised USD 12.3 million at a 0% interest rate (dollar linked bond) to finance its expansion strategy.

Cresud owns a 50.1% stake in the company.

You can find more information at FyO’s official website.

FyO (Company’s presentation)

Agrofy

Cresud has a 17.7% stake in Agrofy.

Agrofy is pioneer in agricultural e-commerce, basically a huge marketplace for agriculture already present in many countries of the region, and with plans of expanding to Mexico in 2023.

This e-commerce platform for agricultural products offers also an electronic wallet ‘Agrofy Pay’ and will be launching ‘Agrofy Credits’ soon, a service to qualify producers and grant them credits through the platform.

Revenues in 2022 are 66% higher than those of 2021. The company is really starting to take off.

Current company valuation after last capital round to finance its expansion reached USD 104 million.

Agrofy (Company’s presentation)

Here’s what Agrofy’s CEO, Maximiliano Landrein, has to tell us about the potential of the company, quoting from an interview with Forbes:

Agrofy is in a huge market that is agriculture, it is 20% of the GDP of Argentina and Brazil, a market of US$ 400 billion by 2025, if we include all categories of agriculture. And we believe that by 2027 5% of agriculture is going to be e-commerce, so we aspire to be in a market of 18 billion dollars of online transactions, part of that flow is going to be in marketplace transactions, and today Agrofy is the number one pure agriculture marketplace in the region and the world.

I believe that in due time this company could go public, adding a lot of value for Cresud’s shareholders.

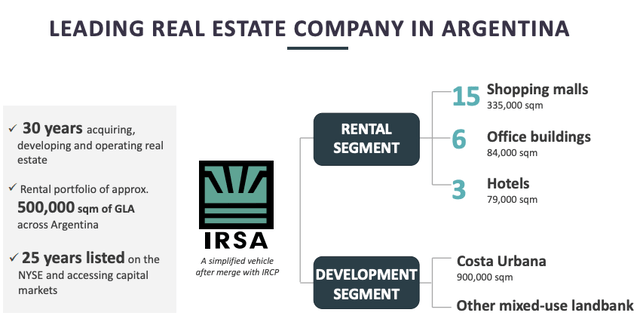

Inversiones y Representaciones S.A. (IRSA)

Cresud is the controlling shareholder of IRSA, a leading real estate company in Argentina, with a 53.7% stake. IRSA’s capital stock is about 810 million shares (81 million GDS trading at NYSE), so Cresud owns about 435 million shares.

In addition to this, Cresud owns 49.9 million stock options, each giving it the right to buy a new share of IRSA at a fixed price of USD 4.3 per GDS, and maturing in 2026. There are 80 million of stock options in total. So when (if) exercised IRSA’s capital stock will be increased to 890 million shares with Cresud owning 485 million, a 54.4% stake.

I wrote several articles on IRSA in the past, the most recently being this one. If interested I suggest you read those articles, that will for sure contain more information than what I can give you here. If you don’t feel like it, no worries. Here’s what you need to know.

IRSA is a leading real estate company in Argentina (Company’s presentation)

IRSA is a very interesting bet on its own. In fact, I consider it to be one of the best stocks to own among Argentine stocks, along with Pampa Energía (PAM) and Cresud itself.

Currently, IRSA is trading at USD 3.5 per GDS at NYSE. That’s a market cap of USD 285 million, but I consider IRSA’s Net Asset Value (NAV) to be over USD 2,500 million, almost 10x more. I explain in more detail how I get to this number in my article on IRSA.

If somewhere down the road, IRSA trades at say 60% of this NAV, i.e., at a market cap of USD 1,500 million, Cresud’s stake would be worth more than USD 800 million. Compare that to Cresud’s current market cap of USD 271 million.

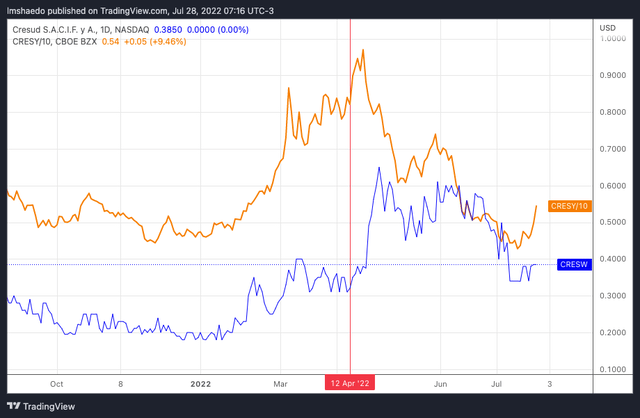

More About Cresud’s Stock Warrants

I mentioned Cresud’s stock warrants briefly when discussing the company’s market cap. But I wanted to dedicate a whole section to this instrument.

Back in March 2021, Cresud issued 90 million new shares to be bought by its shareholders (no dilution) to navigate Argentina’s and covid-19 still ongoing crisis. Almost USD 43 million where raised with this transaction.

In addition to the new shares, Cresud handed its shareholders one stock warrant free of charge per each share subscribed, as an incentive to subscribe the new shares. So for each ADR subscribed, a shareholder received 10 stock warrants free of charge (recall that 1 ADR = 10 shares).

Each stock warrant grants the right to buy one additional share at a fixed price of USD 0.566 per share, and matures in 2026.

So if you are an ADR holder, you need 10 stock warrant to subscribe 1 additional ADR at a price of USD 5.66 per ADR (this is something that seemed to confused a lot of people and wanted to clarify it).

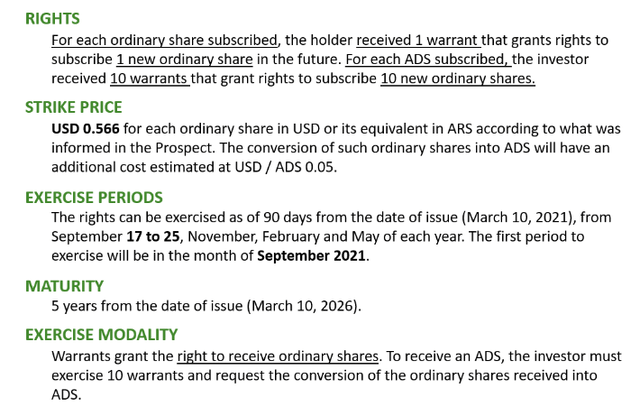

Cresud’s stock warrants (Company’s website)

These stock warrants are trading both in ByMA and NASDAQ, under the tickers CRE3W and CRESW respectively.

Something curious happens with this. Although warrants trade at both markets, they seem to not be convertible one into the other, meaning one cannot buy 10 stock warrants at ByMA and sell them at NASDAQ – or vice versa -, the same way you do with stocks (it is possible to buy 10 shares at ByMA and sell 1 ADR at NASDAQ, for instance). This leads to huge distortions in price at moments, since both markets behave kind of independently.

Stock warrants’ price: NASDAQ (orange) vs. ByMA (blue) (Author)

In the plot above, stock warrant’s price in NASDAQ is represented in orange and its price in ByMA in blue. This last one is obtained by taking the price of each stock warrant in ByMA, which is obviously expressed in ARS, and dividing that by the CCL rate. If you pay close attention to the graph you will notice that I’m using the CCL rate for Grupo Financiero Galicia (GGAL), a public Argentine bank trading both at ByMA and NASDAQ. This is common practice among Argentine investors, since GGAL has the highest trading volume of all Argentine stocks and this makes de CCL rate obtained this way the most representative of all.

These are both the very same instrument, but there’s sometimes a difference of more than 50% in price. Which market has it wrong? We could model this using some fancy math tool like Black & Scholes or similar and take a look at the theoretical price or ‘fair’ price of this instrument, but we won’t do that. We simply note that if we are interested in buying Cresud’s stock warrants now, we better do it at ByMA. If you don’t know have an account in a local broker, feel free to contact me. I am a registered financial advisor and work in one of the biggest brokers in the country.

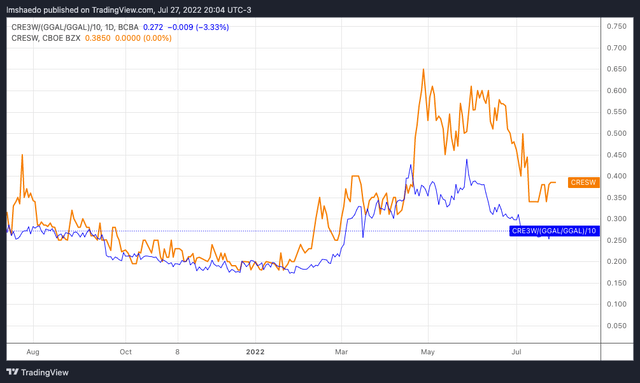

Now take a look at this other chart below. We take the same plot as before but now we add ‘CRESY/10-5.66’ here plotted in violet. What does this represent? Well, by taking the price of CRESY and dividing it by 10 we are looking at the price per common share, expressed in USD. This would be similar than taking the price of Cresud’s shares at ByMA and dividing that by the CCL rate. Both ways would be correct. Now recall that USD 5.66 is the strike price of this stock warrants. So, by subtracting it to the share price, we are essentially getting the intrinsic value of the stock warrants.

Stock warrant’s price and intrinsic value (violet) (Author)

Look at the graph above again. You notice how the intrinsic value (violet) sometimes equals the stock warrant’s price (orange or blue)? When this happens, it means the stock warrants are trading with no extrinsic value. None at all, despite expiring in about four years’ time.

Although there are some reasons that might justify why this happens (we can discuss it in the comments if there’s interest in this topic), I assume this is mostly explained simply by inefficiencies in the market.

When this happens, it is possible to sell stocks and buy instead an equal amount of stock warrants paying no extrinsic value for them. This gives us basically the same exposure to the stock’s price fluctuations. Each USD 1 that stock goes up, stock warrant should go up also USD 1 at minimum. I’m saying at minimum, because if this is what happens then the stock warrant would continue to have no extrinsic value at all… something that should be corrected by the market over time. If stock goes down by USD 1, stock warrant’s price goes down at worst USD 1 (it’s partially offset by gaining extrinsic value).

Not only that, but our capital at stake is reduced significantly, since the price per stock warrant is significantly less than the price of the stock itself.

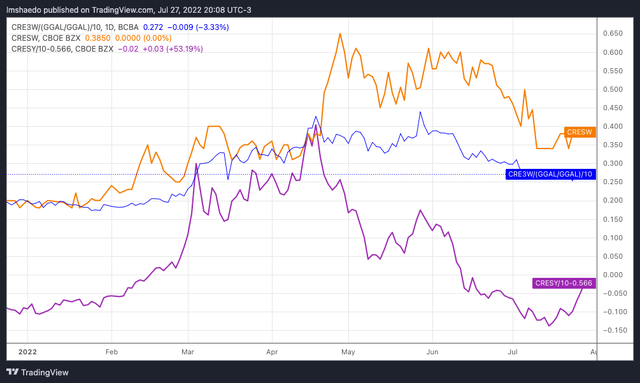

So for instance, on mid April we would’ve sold CRESY at about USD 9 per ADR (USD 0.9 per share) and buying 10 CRESW at about USD 0.4 each (giving us the right to purchase the same 1 ADR we sold) paying no extrinsic value. That’s USD 5 less at risk while basically keeping the same exposure to the stock’s fluctuations in price. This is shown in the graph below, where Cresud share price is shown in orange and the stock warrants’ price in blue.

On April 2021 we would have sold Cresud shares and buy instead stock warrants (Author)

Of course, this kind of trades are limited by the daily volume traded in stock warrants, which is in fact quite small.

Also keep in mind being a shareholder doesn’t equal ‘having the right to purchase a share’ (being a stock warrant holder). For example, if Cresud pays dividends in the next four years we only benefit from that as stock warrant’s holders if the dividend yield exceeds 3% (there’s an adjustment clause in the contract in that case). But this is something each investor should evaluate individually.

In any case, this section’s takeaway should be ‘be always on the look for opportunities’. Market is extremely inefficient in general, but especially with this poor-covered and miss-understood shares from some lost corner of the world.

Share Repurchase Program

It should be mentioned that Cresud has recently announced a share repurchase program for up to ARS 1,000 million or USD 3.125 million, paying up to a maximum of USD 6 per ADS. This is definitely a plus.

The maximum amount might sound too small, and it is. It represents about 1.1% of the market cap. But don’t worry. If current prices last, the Board of Directors will definitely be approving new shares buyback program, one after the other.

The company is limited by local regulations to buy only 25% of the average volume of the daily transactions for the Shares and ADS in the markets during the previous 90 days. This is one of the reasons why the amount is that low: company will have to buy shares at a very slow pace since trading volume is not that significant. The other reason being that the idea here is to try to buy at the lowest prices possible. There’s no reason to announce a massive share repurchase program that might scare the offer away.

A Simple Net Asset Value Calculation

We established before that Cresud’s EV is USD 648 million at current prices of USD 4.6 per ADR.

I know most of you dear readers are here because you are mostly interested in the agriculture business, so let’s try to focus this exercise on that by getting IRSA out of the way. Let’s subtract from this EV what Cresud’s stake in IRSA is worth.

We established before that IRSA’s current market cap at USD 3.5 per GDS is USD 285 million and Cresud owns 53.7% of that (plus almost 50 million stock warrants that we will consider to be worth zero – a conservative approach indeed since I strongly believe this warrants are worth a lot for reasons I will discuss in a coming article on IRSA). So Cresud’s stake in IRSA is worth USD 153 million.

Therefore, we are essentially paying USD 495 million for the agribusiness, i.e., all Cresud’s farms in Argentina, 39.4% of BrasilAgro, 50.1% of FyO and 17.7% of Agrofy.

As mentioned before, Cresud owns 536,000 hectares in Argentina while BrasilAgro owns another 225,000 hectares. Since Cresud owns 39.4% of BrasilAgro, we could say Cresud’s stake in BrasilAgro is about 89,000 hectares. Therefore, Cresud owns 625,000 hectares in total when adjusted by participation.

At a price of USD 495 million, we are then paying USD 792 per hectare (USD 320 per acre), a ridiculously low price. But this price is actually even lower, for two reasons: we haven’t yet considered FyO and Agrofy’s valuation, neither the fact the BrasilAgro has a negative net debt (we are getting 89,000 hectares + some cash).

So let’s go ahead and make a better approximation.

FyO’s last twelve months (LTM) Earnings Before Taxes (EBT) was USD 21.2 million. I’ll go ahead here with what I think is a conservative approach and value this company at about USD 40 million. Cresud’s 50.1% stake would be worth USD 20 million.

After last capital round, Agrofy is valued at about USD 104 million. Cresud’s 17.7% stake is then worth USD 18.4 million.

BrasilAgro has a negative net debt of BRL 170 million, or about USD 32.3 million. Cresud’s 39.4% stake is USD 12.7 million.

When taking all this into account, we find we are paying USD 444 million for those 625,000 hectares. That’s a price of USD 710 million per hectare, or USD 287 per acre.

Granted, not all these hectares are productive, and to be fair some will never be (it’s part of the business model). In fact, half of the total hectares are productive (agriculture or cattle). If we value at zero those non-productive hectares (they are certainly not worth zero…), then we are paying USD 1,420 per productive hectare. Seems like a great deal.

Of course, the correct way of doing this would be taking each farm individually, and its productivity, and all those factors and value them individually. We could go ahead and do this here, but I will leave this as an exercise for the reader. In my view, USD 710 per hectare is a great deal, especially considering how conservative we were with the valuations. We even assumed a zero value to 50 million stock warrants that could easily be worth hundreds of millions of dollars (again, I will elaborate this on an upcoming article on IRSA).

Investor Takeaways

When we buy Cresud’s shares we are getting a massive diversified agriculture portfolio at a great price, two agriculture-related e-commerce startups with true potential of becoming unicorns, 50 million stock options on a company with tremendous upside potential, and the controlling stake on a real estate co. trading at less than 15% of its NAV.

It’s not hard to see how Cresud could easily go back to USD 20 per ADR as has done so many times in the past, when some of these variables line up, i.e., either the market pays a more reasonable price per hectare, IRSA trades at a closer price to NAV, or one of both of the e-commerce companies take off, or a combination of all three. There’s margin of safety all over the place and since market cap (and EV) is so depressed at the moment, any minor improvement in any of these variables can make the stock go up two or three fold easily.

For instance, we noticed before how IRSA trading at 60% of its NAV would make Cresud’s stake in the company be worth USD 800 million. That alone is 2.5x Cresud’s current ‘fully diluted’ market cap. And we haven’t even considered an improvement in the agri business which as seen before, is trading at a great discount to fair value.

Cresud’s stock price (Seeking Alpha)

All in all I think Cresud is one the best stocks out there to get exposure to the agri business. It’s a fair simple but diversified vehicle (even IRSA as of today is extremely easy to understand) and has been so far overlooked by investors either due its zip code (most funds are not even looking at Argentina right now) or because they just don’t understand the particularities of the Argentine stocks. To emphasize this point, just let me remind you that most investors even get the market cap wrong – they get more than 2x the real market cap! That right there is what I call an opportunity.

Be the first to comment