Bear Market Distribution Strategies DNY59

[This article summarizes themes that we covered in earlier articles for our Inside the Income Factory members on August 8th and September 21st.]

Credit Funds vs. Equity Funds: Collecting Real Cash vs. “Eating Your Seed Corn”

Anyone focused on the market value of their investments has probably had a pretty challenging year. But investors focused on maximizing the income their portfolios generate, rather than on paper profits and losses (most likely losses), have had a more encouraging experience.

Closed-end funds are particularly attractive to income investors because:

- The funds’ managers, knowing many closed-end fund investors prefer to receive most of their return in the form of cash dividends, make that a priority in their investment policies (choosing high dividend or interest paying assets) and in their distribution policies (paying out most or even all of their fund’s total return in the form of cash distributions).

- The closed-end structure of the funds allows them to invest in more complex and less liquid asset classes of the sort that often pay higher distributions,

- Closed-end funds can do that because they know that (unlike typical open-end mutual funds) they are largely immune to “runs on the fund” from investor redemption demands

- Astute (and patient) closed-end fund investors can often buy funds at a discount from their actual net asset value (“NAV”), which means the investors end up with more assets “working” for them than they actually paid for.

- Similarly, buying assets at a discount lessens risk to the investor, since the investor may be receiving (to them) a 10% yield while holding an asset they bought at a discount whose actual yield (on its face amount) is only, say, 9.5%. So they’re being paid to take a “10% risk” while only taking a “9.5% risk.” Generally the risk associated with particular asset classes increases as the yield paid by those asset classes rises. So the cumulative effect over many years of getting paid a higher rate than the actual face rate on the instruments you’re holding because you’ve bought many of them at a discount, is like tipping the “risk/reward” balance in your own favor.

Not All Income is The Same

Just because a fund pays a distribution doesn’t really mean that it represents income.

Whoa, you say! I get the check in the mail, or the money is deposited in my brokerage account or IRA, but it may not be “income?”

That’s right. The fund may make us a distribution payment that represents a 10% yield (annually) on its market price (Or on its net asset value; yields are often computed on both). But unless the fund actually earned the amount of that distribution during the period in which it is being paid, it doesn’t really represent “income” to us as investors. That’s because if the fund hasn’t earned what it is paying us, then it is really just paying us back a piece of our own investment. So we have fewer assets working for us after receiving the distribution than we did at the beginning of the period for which the distribution is being paid.

A fund paying us a distribution can have earned it in one of two ways:

- It can collect it itself as cash “distributions” (of a sort) from its own investments. In other words, if the fund owns stocks and bonds, it can collect dividends and interest from its own investments and then use it to pay its own distributions to us, its shareholders (after it first pays its own expenses of running the fund). We call this “Net Investment Income.” It is all the cash received by the fund as dividends, interest or other cash payments, minus fund expenses. For some funds, Net Investment Income (or “NII”) is enough to pay its entire distribution. Typically this would include funds that hold loans, high yield bonds or other fixed income securities, where the interest at 7% to 10% or even higher (depending on the asset class and the risk involved, etc.) would provide sufficient cash flow to fully fund a high distribution.

- But some funds do not collect enough dividends or interest to have sufficient NII to pay their entire distribution from that source. Most equity funds fall into this category. It’s not surprising because the average common stock, especially the sort of stock a “growth” or “dividend growth” fund would buy, only pays a yield of 2 or 3% (often less). Even high yielding dividend stocks, like utilities, usually don’t pay yields much above 4 or 5%. So stock funds, unlike credit and fixed-income funds, do not generate dividends or interest (i.e. NII) sufficient to pay the sort of distributions their investors expect.

- So where do equity funds get the money to pay their distributions?

- The obvious answer is capital gains. Unlike credit and fixed-income funds that have portfolios that earn cash via dividends and interest, equity funds have portfolios that grow in market value (i.e. achieve capital gains). So in order to pay a distribution the fund actually sells off a portion of its now-increased-in-value portfolio in order to fund the distribution.

Think of it as two different closed-end fund “models” for earning and distributing:

- One where there is a more or less “static” portfolio (static in the sense it may remain largely the same in terms of market value, even though it is actively managed to maximize its income production) that generates a high level of interest and dividends which make up most or all of the “total return” of the fund. That cash income, which, minus its expenses is its NII and which I often call a fund’s “river of cash,” can support the fund’s distribution without ever having to touch the “core portfolio” of the fund.

- The second is the equity fund model, where the fund has a small amount of cash income from dividends, and relies on an additional capital gain (i.e. annual increase in the value of its portfolio) to make up the difference and achieve an average equity return of 9 or 10%. For example, if the fund generates cash income of, say, 2 or 3% in dividends from its own portfolio, then it must be hoping to grow itself by an additional 7% or so every year in order to earn its total return of 9 or 10%. That means if it is paying a distribution of 7 or 8%, or more, that most of that distribution depends on its achieving capital gains to support it; which capital gains it has to “monetize” by selling off a portion of its portfolio, which (in theory) it can do because its portfolio is now larger than what it was at the start of the year by the amount of the capital gain.

- [Spoiler alert: What happens if there is no capital gain?]

The Challenge: Interest is predictable; Capital gains are not

Credit and other fixed income funds can project interest income into the future like clockwork. So distributions funded by interest income or equivalently predictable cash flows (i.e. NII) are pretty stable. (Not totally, because defaults happen, interest rates change, etc. But those events are all predictable and capable of being modeled much more than stock market ups and downs).

Capital gains come and go. Even really good equity managers that achieve average returns of 10% and higher for decades, have good months and bad months, good years and bad years. But closed-end fund investors want regular, predictable income. So equity funds typically institute “managed distributions” where they smooth out the difference by picking a distribution rate that averages what they feel they can comfortably achieve over a long period of time, and then set that as their regular distribution. Some months they pay out less than they actually earned, sometimes more, but the theory is that it will all smooth out over time and they will have actually earned as much or more than what they paid out. If they earn more, then they can pay out a special distribution at the end of the year, or even raise the amount of their managed distribution.

That’s the theory. The problem is that “smoothing” only works if you have both ups and downs occurring on a pretty regular basis. If it’s all downs and no ups for a considerable period of time (like, for example, from 9 months ago when the stock market peaked) then it’s hard to “smooth out” what is essentially a one-way street.

I have written previously (link here) about how “managed distributions” can lead to an erosion of capital value if the “peaks and valleys” they are intended to smooth out turn out to be all valley and no peak for an extended period of time. That’s because managed distributions amount to essentially borrowing capital that’s already part of your capital base (paid in capital, past earnings that have already been accounted for, etc.), monetizing it (i.e. selling assets to raise cash) and then paying out the cash as a distribution.

Implications for Closed-End Fund Investors

The bottom line for investors is that there is a very real difference between a distribution paid largely from current cash earnings (i.e. Net Investment Income) and one paid largely from capital gains. In times when overall market prices are rising, or even flat enough that a skilled portfolio manager can achieve gains, it makes little difference.

But in times like we’ve been experiencing so far this year, when the market has been dropping and few funds have capital gains, the difference between the two types of funds becomes very clear, and critical:

- Credit and other fixed income funds produce a regular flow of cash (i.e. dividends and interest) from their portfolios that supports their distribution; regardless of what happens to the market price of the portfolio itself. The portfolio (the Income Factory®, as we often call it) that produces the cash output, can go up and down but it’s only a paper loss as long as we don’t sell it and turn it into a real loss. So not only are we generating the cash flow to cover our distribution, we are also keeping the portfolio intact (not selling it to raise cash), so it can benefit from the rise in market prices when it eventually happens.

- Equity funds do not produce a regular flow of cash, other than the 2% or so (often less for “growth” funds) of dividend yield that is largely consumed in paying the fund expenses. So they have to sell off (“monetize”) a portion of their portfolio to pay their distribution. If the portfolio has grown over the course of the period, then selling off some of it that represents part or all of the capital gain they generated is fine, because the portfolio that remains is still the same or even a bit larger than what they started with. But if there was no capital gain, and they try to maintain their distribution, it means selling off part of the original portfolio (which is not only no bigger than what they started with, but may even be smaller if they suffered a loss during the period.) Either way, by continuing to pay their “managed” distribution even though they made no gains, they are decreasing the core portfolio that the fund has to rely on for earning future dividends and capital gains. Having “eaten their seed corn” by invading the core portfolio to pay distributions, the fund will have to achieve even bigger capital gains, percentage-wise, in the future, to get back to where they were when the downturn started.

Here are Some Real-Life Examples

A quick look at some representative credit and equity closed-end funds makes the difference quite clear. These are all top-rated funds, in terms of longer term records. But the difference in NII distribution coverage, the percentage of the fund’s distribution covered by its interest and dividend income (its most predictable, “business as usual” income), is dramatically different between credit funds and equity funds, showing how much the equity funds have to rely on capital gains to make up the difference.

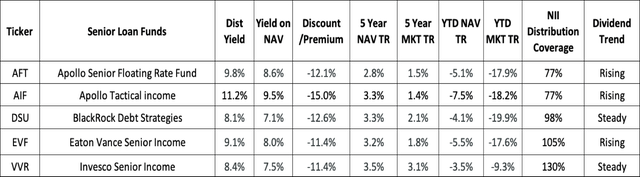

Here are some top corporate loan funds, an asset class that is the most senior and secured in terms of credit protection, and also is floating-rate and therefore not exposed to interest rate risks (even benefits from rising rates).

Notice some of the funds – Blackrock (DSU), Eaton Vance (EVF), Invesco (VVR) – fully cover all or virtually all of their distributions with their NII. the other two Apollo funds (AFT) and (AIF) cover over three quarters of it, but still rely on some capital gains or other portfolio wizardry to pay theirs. They must be confident they can continue it since both Apollo funds raised their payouts substantially in recent months. So none of these funds should have to invade their core portfolio at all, or very much, to continue their current portfolios. Meanwhile with their large price discounts, plus the big underlying discounts currently prevailing in the corporate loan secondary market, they have room to benefit from price increases in the future as capital markets recover generally.

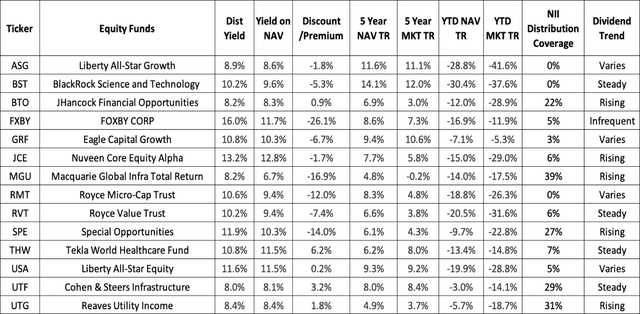

Here is a selection of highly regarded closed-end equity funds. They tell a different story. Most of them have virtually no Net Investment Income at all, which means whatever interest or dividends they collect is eaten up by the fund administrative and other costs. Those that do have some NII generally have very little, not enough to make much of a contribution to their distributions. The exceptions to this are the utility and infrastructure funds – Macquarie (MGU) Cohen & Steers (UTF) and Reaves (UTG). The other exceptions are Special Opportunities (SPE) which is not your typical equity fund, but holds a lot of other closed-end funds that pay higher dividends than the typical equity holding; and John Hancock (BTO) which holds mostly banks and other financial institutions that also pay higher dividends than the average equity.

Be the first to comment