MicroStockHub/iStock via Getty Images

Equity Returns In The Credit Market

Lately I’ve mentioned in other articles (like this one) how the market seems to be penalizing credit investments unduly for the anticipated defaults and losses that it fears will occur in an economic downturn or recession. Some have called this the “worry discount,” but whatever you call it, markets seem to overcompensate investors for the very real but mostly predictable and quantifiable risks that exist in credit markets. Making matters worse is the fact that the average investor has little appreciation that headline “default” estimates are always a multiple of what actual credit losses turn out to be, after typical recoveries of 50, 60 or 70% of principal on defaulted debt are taken into account.

Credit risks are, by definition, less than the risks that exist in equity markets, given how credit (e.g. loans, bonds, etc.) sits above equity on corporate balance sheets and has to be repaid or else the equity below it is worthless. So an investor who owns equity in mid-cap or small-cap stocks, whether they realize it or not, is also taking the risk on all the high-yield bonds and loans on the balance sheets of those same companies; debt that has to be serviced and repaid if the equity below it has any chance of surviving, let alone increasing in value.

It is not surprising that the media and various commentators tend to go overboard pointing out the risks – both real and exaggerated – that exist in the corporate credit markets. Having been both a banker, credit executive and also a financial journalist over my multi-decade career, I know from experience what sells magazines and newspapers, and in our more recent electronic publishing era, what generates clicks on on-line sites (like Seeking Alpha).

“Chicken Little” articles with someone yelling “the sky is falling” have always been the model for getting journalistic attention, and that continues today. So articles hyping how bad things are going to get, whether in the economy generally or in specific markets, will always get more attention from both editors and readers than more sober articles that say: “Yes, there are issues to be addressed and things may get ugly, but overall the economy (or Company X) will manage to muddle through.” Stories like that are probably more accurate, but are not nearly as exciting or interesting….and surely don’t sell as many subscriptions.

The “Worry Discount” – A Real Life Market Example

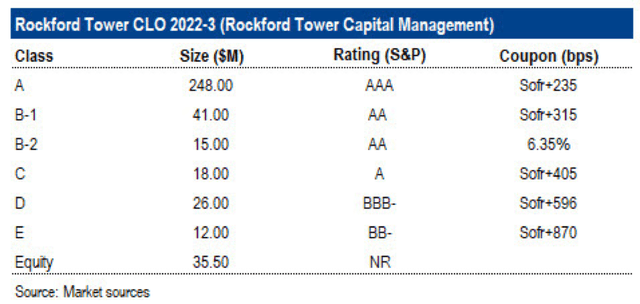

Here is a description of the capital structure of a new collateralized loan obligation (“CLO”) just being launched. It shows all the different debt tranches that will be used to fund the CLO’s investment in a pool of senior secured corporate loans. (For background on CLOs, which are “virtual banks,” check out this article.) Notice the top tranches, which get paid first before the lower-rated debt tranches (and all of which get paid before the equity gets anything), are rated AAA through A, and even those highly rated and “super safe” issues are yielding rates that would normally make an investment grade investor’s mouth water.

SB

Look at the triple-A rated tranche: The base rate (SOFR or “secured overnight financing rate”) is currently 3.8%, plus a spread of 235 basis points, for an all-in coupon of 6.15%. That’s a heck of a return on a triple-A credit, and it may understate the actual return if the investor is able to purchase it at a discount (which may be the case, although not always). As you move further down the liability stack, discounts become more typical.

Let’s consider the single-A tranche. Single-As are extremely good credits, with defaults that are few and far between. The base rate SOFR at 3.8%, plus a spread of 405 basis points, equals a coupon of 7.85%, which is what high yield bonds were paying not that long ago. And the tranche rated BBB- pays SOFR plus 596, which is 3.8% plus 5.96%, or 9.76%, a pretty mouth-watering yield for what is still an investment grade credit. (And that’s before the benefit of any upfront discount.)

But it’s down in the double-B rated sector where the real fun begins; and that’s the arena that a number of the funds we invest in are actively engaged in, like Eagle Point Income (EIC), as well as XAI Octagon Floating Rate (XFLT), and Ares Dynamic Allocation Fund (ARDC).

Note how the spread over the SOFR base rate has jumped up to 870 basis points. That means a coupon of 3.8% plus 8.7%, or a total of 12.5%.

Sources closer to the CLO market tell me it would not be unusual for CLO sponsors to have to discount significantly the lower tranche debt, as they do the equity, in order to place it initially with investors. We know from EIC’s October month-end report that double-B rated debt carried on its books at that time was marked to market at a 19% discount. If we assume a more modest discount of 8% on newly issued double-B CLO debt, that would still add another 8% capital gain to be earned when the debt matures at par, typically about 5 years later. So if we amortize that 8% discount over 5 years, that adds another 1.6% to the yield, bringing it up to 14.1%.

But there’s more. Since we bought at a discount and only paid 92 cents on the dollar to buy the asset, rather than par of 100, the yield on the actual amount of our investment is 14.1% divided by 0.92, or 15.3%.

Obviously, there are assumptions in here that may vary a bit from deal to deal, but this gives us an idea of how “rich” the high-yield credit market, especially the more specialized sub-sector of CLO debt, has become as markets have tightened in anticipation of an economic downturn and the increased credit defaults that are expected.

Why does CLO debt pay a premium over normal corporate debt of the same rating?

Nobody can prove it, but my own theory is that CLOs are perceived by some traditional, mainstream investors to be more complicated than ordinary corporate structures. So the securities CLOs issue, both debt and equity, end up paying a “complexity premium” as a result. It doesn’t mean they are riskier than equivalently rated corporate debt. But if the complexity discourages some institutional investors from buying them (perhaps because their investment charters don’t include them, or they don’t want to have to explain more complex instruments to less technically sophisticated oversight committees or boards of directors, etc.), that essentially “shifts the demand curve” as the economists say, and the lower demand could mean higher clearing prices on the securities they issue.

Whatever the reason, investors who are willing to climb the learning curve on CLOs and other higher-yielding securities reap the advantages, as we try to do in our model Income Factory® portfolios. I recognize that funds that invest in CLO debt and equity may not be everyone’s cup of tea, which is why I list them as “more aggressive options” in our list of investment choices.

As always, I look forward to your comments and questions.

Steve

Be the first to comment