Eric Francis

Let’s invert the usual question. Charlie Munger, after all, insists on it as a core principle: always invert. In this article, the question is not whether a stock is right for you but whether you are a good fit for the stock. While attempting to answer this question, potential shareholders may gain insight not only into the company in question, Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A)(NYSE:BRK.B), but also into themselves.

There’s nothing quite so revealing of your identify as an investor as the decision whether or not to own Berkshire. You should start with the knowledge that you are probably not going to change Berkshire Hathaway. Many have tried, most of them journalists, and they have so far failed to get Berkshire to change its fundamental policies. Very few Wall Street analysts make a serious attempt to cover Berkshire. From the outside it looks easy, but analysts quickly see that it isn’t and move on to easier targets. In a couple of cases I sent a private message taking a well-known journalist to task for not bothering to acquire deep enough knowledge about his beat. One whose name and publication some of you would know took my criticism seriously enough to study up until he understood Berkshire well enough to change a few of his views.

The current Berkshire came into being when Warren Buffett took control of a failing textile company in 1964. The fact that the original Berkshire made coat liners and dated back to 1839 isn’t so much its pedigree as proof that the only permanent thing is change. Berkshire has always been about change with a few leaps in the sort of businesses held within it. The winners have succeeded so well that the occasional failures have shrunk into insignificance. Ownership of Berkshire has also evolved. When Buffett closed his fabulously successful investment partnership in 1969 he folded its assets into Berkshire, giving his former partners the option of receiving Berkshire shares in exchange for their holdings. Many took that option, and an astonishing number who worked at ordinary jobs wound up being multi-billionaires. Omaha, Nebraska, the home of Buffett and Berkshire, is one of those fat-tail outliers which destroy the bell curve for random distribution of wealth.

The original partnership continues to be the foundation of Berkshire’s unique culture. For most of Buffett’s former partners it wasn’t just that they had gotten rich but that hey knew going back to their partnership days that Buffett and all who worked for him were of the highest integrity and completely to be trusted with their savings. Buffett in return treated them as family just as he had when they were partners. Many of them were in fact family members or neighbors who lived not far from the simple house he bought for $31,500 in 1958 and continues to live in today.

Buffett himself has acquired very few billionaire perks and has demonstrated what all well-informed investors know to be the foundation of investment success: frugality. Values like that are easy to ignore in what became the greatest investment success in history. Another is integrity. Buffett’s partners had trusted him with their money and he was determined to live up to that trust. This principle has carried over to Buffett’s view of Berkshire shareholders. Over the 53 years since taking responsibility for his partners in BH he has beaten the return of the S&P 500 stock index by 3,641,613% to 30.209%.

There is a strong loyalty that goes in both directions between Buffett and his shareholders. Buffett acknowledges this special relationship and continues to think of his shareholders as partners. This sort of informed trust gives management an uncommon degree of freedom. Buffett’s shareholder base generally takes the long view and doesn’t pay great attention to quarterly returns. Buffett’s investment decisions have usually been right, but when they have been wrong he admits it and takes full responsibility. You could produce a manual for CEOs around that principle alone. Buffett does not make quarterly earnings calls, and has a good reason: they focus on the wrong time frame. His annual meeting in Omaha, however, has grown to draw such crowds that it is known as the Woodstock of capitalism.

Berkshire is a special company with special leadership and special long term results. Why wouldn’t it have special shareholders? That’s a point to consider as you mull over the decision about buying Berkshire. Unless you own it through a fund or ETF such as the Vanguard S&P 500 Index ETF (VOO) or Value Index (VTV), nobody is forcing you to own Berkshire. It’s not for everybody. On the other hand, it’s not like the test you have to pass to become a US citizen. You don’t have to fill out a long questionnaire and demonstrate any knowledge about the company. Nobody can stop you from buying Berkshire, no matter how you feel about the sections below. The points below will simply provide you with certain basic information so that you won’t be ambushed by basic facts you may later wish you had known.

You Should Not Expect Excitement With Berkshire

Berkshire Hathaway does not provide its owners with excitement. You probably won’t get astonishing earnings reports which move the stock price up or down 10% or more. It’s not Tesla (TSLA) or Meta (META), both of which have made round trips in passing Berkshire’s market cap and then falling well below it. Berkshire is, frankly, dull. For serious investors dull is good. Berkshire is not a stock for speculators. It just isn’t volatile enough to make a trader quick money.

Berkshire has a low value for Beta. Beta is the modestly mathy calculation for how much a stock moves up or down compared to the average stock. The neutral score is 100. Berkshire’s Beta is 81. Many studies have shown that stocks with low Beta outperform the market. A part of this is in the arithmetic. If a stock falls 50% it must then rise 100% to get back to breakeven. A 30% decline requires as requires a 43% recovery.

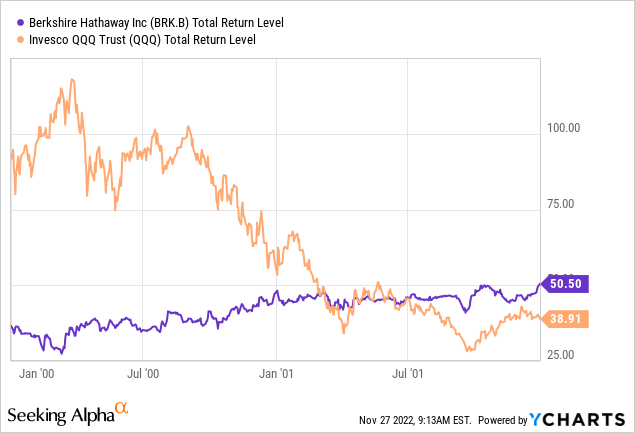

In some markets it has actually had negative Beta, which makes it a helpful haven in some bear markets. During the years of the dot.com crash starting in 2000 Berkshire overpriced in 1998 (a rare condition which led Buffett himself to discourage investors from buying it) rose steadily while the NASDAQ 100 index (QQQ) was crashing. In a coincidence which was not so coincidental Berkshire stock bottomed on the exact day that the NASDAQ 100 topped. It chugged along for most of a decade as the dot-com favorites crashed and burned. Here’s the chart:

You Must Accept The Fact That Berkshire Underperforms In Bull Markets

Berkshire underperforms in bull markets – both Buffett and Charlie Munger have acknowledged this fact – but it makes up the ground and then some in bear markets. The chart above shows a microcosmic illustration. Long term Berkshire shareholders will have their patience tried as in the years of the dot.com bubble and the recent ten year dominance of tech/media stocks. Toward the end of bull markets there are often stories in financial magazines arguing that Buffett is behind the times and has lost his touch. These stories are a signal to start selling popular market leaders and started buying Berkshire and other value stocks. It worked as a tell in 2000 and again in 2021.

You Must Have The Patience To Be A Long Term Investor

Buffett famously said that “time is the friend of the wonderful company and the enemy of the mediocre.” This could be printed above the door in Kiewet Plaza, Omaha, although such as garish self-aggrandizing display would be out of character for Buffett and Berkshire. Berkshire’s earnings are a bit lumpy with different forces driving the occasional down year in one or more of its subsidiaries. BNSF Railroad and Berkshire Hathaway Energy as well as many other non-insurance subsidiaries are sensitive to the economy while the insurance side has occasional off years for underwriting or losses due to catastrophic insurance events. Since Accounting Standards Update 2016-1 went into effect in 2017 Berkshire must report aggregate changes in its stock portfolio producing what Buffett characterized as “wild and capricious” nominal swings in earnings which shareholders should ignore. In the long term these things tend to average out.

In the long run the overall value of Berkshire increases at a good clip. Over the 53 years in which it has been controlled by Buffett its average annualized return has doubled that of the S&P 500, roughly 20% to 10%. Buffett has acknowledged that Berkshire’s large size has greatly narrowed this margin which might in the future approximate 2%. Periods of tech and innovative business models have helped the S&P 500 to do better over the past decade, until recently that is. Berkshire has recently taken the lead as it often does in bear markets. The movement in favor of Value, if it continues, should favor the outperformance of Berkshire.

You Should Understand Berkshire’s Unique Corporate Structure

Berkshire is a conglomerate. Unlike the conglomerates of the 1960s and 1970s which gave the term a bad name, Berkshire is synergistic. The whole is greater than that parts. Its wholly owned subsidiaries and stock portfolio put its insurance float to work while covering future payment of claims. Its businesses include earlier favorites which have a high return on capital and require little new investment. They throw off cash that can be employed elsewhere while starting in 1998 more recent acquisitions in regulated industries like BNSF railroad and gas and electric utilities of Berkshire Hathaway Energy earn a reliable return but require a large amount of capital.

In operational terms Berkshire is highly decentralized. Its subsidiaries are divided into insurance and non-insurance units. Managers are given wide leeway. Its capital allocation, on the other hand, is centralized with corporate headquarters in Omaha. The Omaha office has just 30 employees. Buffett’s two lieutenants on the investment side work from a distance. There are none of the layers that weigh down many companies despite that fact that Berkshire has over 370,000 employees and owns the most land of any American corporation.

The system of decentralized operations and centralized capital allocation operates smoothly. The emphasis on capital allocation embodies the essence of capitalism. When badly informed journalists call for a future breakup of Berkshire, informed Berkshire shareholders cringe.

You Should Have One Major Goal: Compounding Your Capital At Low Risk

The primary goal of Berkshire shareholders is to compound their money. The best measure is Return on Equity. Going into the COVID pandemic share buybacks had begun to help these numbers recover to about 9-10% after falling to about 8% because of the increasingly large cash position which then was parked in T-Bills with a return close to zero. Buybacks which in a couple of years were around 4-5% of market cap served to improve the ROE. The ASU 2016-1 rule has made it harder to calculate ROE because of the swings in market value of the $350 billion publicly traded stock portfolio. The numbers below, all in billions and all taken from BRK Annual Reports, show the complexity of factoring them into the ROE.

| Year | Market Value | Cost Of Position | Capital Gains |

| 2017 | 170,540 | 74,676 | 95,864 |

| 2018 | 172,757 | 102,867 | 69,890 |

| 2019 | 248,027 | 110,340 | 137,678 |

| 2020 | 281,170 | 108,620 | 172,550 |

| 2021 | 350,719 | 104,605 | 246,114 |

Cost Basis increased by $29,929 while Market Value increased by $180,179, netting out to gains of $150,250. Much of it is reflected in the numbers for 2018 and 2019 when the Cost Basis increased through the middle of 2019 due to purchases of Apple (AAPL). Much of the return followed the middle of 2019 when Apple’s price continued to rise sharply as Berkshire’s buying tapered off. On average the Price to Cost Basis more than doubled for an annualized rate of over 15%. That’s enough to pull ROE up sharply as the value of the publicly traded portfolio is now almost half of Berkshire’s market cap. That’s before dividends of over $6 billion this year or about 1.7%. In sum Berkshire will probably compound your money at a rate around 12%, a number which Buffett has used in the past.

You Will Not Receive A Dividend, But If You Need Cash You Can Manufacture One

This is the major sticking point for some potential investors, and it is a common criticism used by journalists who fail to see the large picture. The important thing is to remember that no one is forcing you to buy Berkshire. You have many options in dividend stocks and fixed income instruments. If every stock you own must pay a dividend, you should probably look elsewhere. Buffett has often said that he opposes a dividend as long as there are better things to do with free cash flow. His order of priorities are (1) internal reinvestment, (2) acquisitions or stock purchases, (3) share repurchases, and (4) dividends. His shareholders agree. In 2014, 97% of the shareholder vote opposed instituting a dividend.

In his 2012 Shareholder Letter Buffett used a parable of three business partners to lay out the case against a dividend. Rather than saddle all three with a 4% dividend he posited the alternative of having the partner who needed cash sell 4% of his shares regularly. Over the long term the partner who sold 4% of his shares did much better in the long run. The full story is worth reading.

The best case, of course, is provided by buybacks. In the years when Berkshire does share buybacks any shareholder can sell up to the percentage of market cap repurchased without losing percentage ownership of profits and cash flow. Almost all actual Berkshire shareholders have the savvy to carry out the simple steps to manufacture the needed dividend.

The absence of a dividend is a powerful benefit to many shareholders who have owned Berkshire for a long time and have large positions. For many of them a dividend would come with a heavy burden of taxes payable to the IRS at their individual income tax rates. That’s a heavy price to pay for the convenience of a few shareholders who don’t wish to take the trouble to study and carry out the relatively simple and tax-efficient alternative of selling a few shares. Remember that shares sold will generally be taxed at the lower long term capital gains rate.

You may well wonder why Buffett seems to like receiving dividends, over $6 billion from Berkshire’s stock portfolio, while he resists paying them out to his own shareholders. It starts with the tax problem for his shareholders, as mentioned above. Individual investors are often taxed more favorably on capital gains. It’s the other way around for corporations, which are taxed on capital gains at their regular rate, 22% and likely to rise. For non-insurance businesses the corporate tax rate for dividend is 10% (14% for insurance businesses).

These tax rates explain partially or fully a number of Buffett’s actions. For companies more than 20% owned, which for Berkshire would be Kraft Heinz (KHC) and Occidental Petroleum (OXY), the tax on dividends falls to 7%. This accounts in part for Buffett’s pushing his percentage ownership of OXY over 20%. Long term holding Coca-Cola (KO) now has a cost basis so close to zero that taxable capital gains constitute close to 100% of its valuation. Despite its lack of growth and short runway for dividend increases, Buffett probably chooses to keep KO because selling it would sacrifice over 20% of its value to the IRS. Keeping it Coke provides a 2.81% dividend yield taxed at only 10%. Buffett covers all this arithmetic in his 2017 Shareholder Letter. In sum, Berkshire Hathaway is one of the last available legal tax havens for individual investors, compounding internally without taxation. In many respects it resembles an IRA. All taxes can be deferred into the distant future.

You Should Accept The Fact That A Shares Have More Voting Power Than B Shares

A Shares are original never-split stock shared by Buffett and his original partners and now trading for over $470,000. B Shares were created in two stages. The first 30 to 1 split was done in 1996 in response to the threatened creation of unit trusts which would have exploited Berkshire’s successful history to draw small investors who would have paid high fees and commissions. The second split, at 50 to 1, was done to accommodate small investors who preferred Berkshire shares to cash in the 2010 acquisition of BNSF Railroad in 2010. The current B Shares have 1/1500 the value of an A Share.

Understanding that the splits would eventually bring in a large number of new investors who would be relatively uninformed about BH, Buffett included a lower voting power for the B Shares. Each A Share thus has 10,000 times the voting power of a B Share, giving owners 6.67 times more influence per share. This action presumably was taken to preserve the culture supported by long term owners and protect, for a period of time, the policies which defended them against such things as initiation of a dividend.

You May Wish To Study Up On Berkshire And ESG

Buffett and Berkshire occasionally get some public flak on ESG issues. The disproportionate influence of A shareholders is sometimes cited as a Governance issue, with Buffett’s firm control of policy on things like dividends cited as a result. Set against the argument that Buffett has too much power of decision. It’s a rare case in which executive compensation not a factor. Buffett’s salary is a straight $100,000 and Berkshire provides no shares or stock options to its executives. On this and all ESG issues Buffett must attempt to reconcile the call for democratic governance with the actual best interests of the majority of his shareholders. Criticism based upon Governance alone miss the nuances of this question.

A company as large and diverse as Berkshire is inevitably going to bump into a number of social and environmental issues. Most recently this has been focused on Buffett’s recent major purchases of large positions in two fossil fuel companies, Chevron (CVX) and Occidental. In his 2020 Shareholder Letter Buffett spoke in detail of the challenges in developing an electrical grid from the remote areas sourcing wind and solar to the population centers which consume most of the energy. Speaking with the inside knowledge that comes with owning Berkshire Hathaway Energy he presents the pragmatic view that building out this grid was going to be a massive and expensive project requiring patience. In the meantime BHE is in the middle of an $18 billion project begun in 2006 and scheduled to finish in 2030 extending and updating its Western grid. Since 2006 its cash flow has been channeled to the project, which in the very long run should be highly profitable. To be a happy Berkshire investor one should understand and accept this realistic approach to balancing ongoing human needs with environmental concerns.

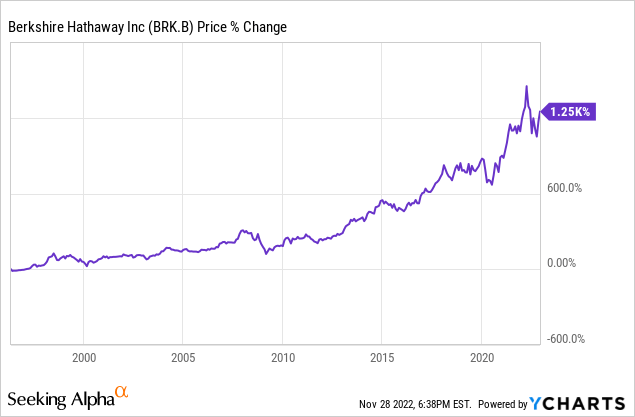

This Long Term Chart Shows Berkshire’s Historic Growth

The important thing to notice is that setbacks having to do with market shifts between Value and Growth and/or economic events rapidly become blips within the long term pattern.

You Should Have Faith In The Succession Plan Until Proven Otherwise

Warren Buffett is a healthy and vigorous 92. The question of Berkshire’s future without Buffett is something we must nevertheless think about. Buffett’s preparation has involved naming Greg Abel, Vice President for Berkshire’s non-insurance businesses, as his successor. This was a more or less inevitable choice because Abel’s experience encompasses so many businesses on the non-insurance side. He has also stood at Buffett’s side on many bolt-on acquisitions particularly in the area of gas pipelines and storage facilities and has also been involved in attempted utility acquisitions in which Berkshire was ultimately overbid by hedge funds. He has had many years to absorb Buffett’s thinking on acquisitions and corporate strategy. He has created and managed Berkshire Hathaway Energy, Berkshire’s fastest growing subsidiary.

No one can replace Buffett, but Buffett’s ability to rise above personal ego has undoubtedly made it easier. What will Berkshire do in the future with the massive cash flow which is thrown off at a rate of about $3 billion a month? More buybacks are one possibility, probably my favorite if wonderful low-risk acquisitions are not available, but it is fortunately not my decision. As rates have risen the pressure to take action has diminished and perhaps we may be entering an era when there is less cheap money, making acquisitions easier for a company with free cash flow in excess of $30 billion. As a Berkshire shareholder, you should be confident that these questions have been talked through in detail. Time is on the side of a wonderful company whose major problem is the good problem of huge cash flow. It deserves the benefit of the doubt.

You Should Try To Have A Charitable View Of The Nonbelievers

Nothing rankles for a member of the Berkshire community quite so much as a poorly informed person popping off on what Berkshire needs and what actions Buffett or his successor should take. This is a common phenomenon in the financial press and the negative comment streams often sound like responses to an outsider who has criticized the individuals and values of your own family. I certainly feel that way from time to time and occasionally add my views to the thread. What do these outsiders think they know to justify them in calling for a dividend or expressing the hope for a future breakup of Berkshire? How about those who want to impose their views on ESG issues? They just don’t get it, right?

Little by little I have tried to temper my views and provide comments intended to educate rather than lambast. We Berkshire shareholders stand by the just and reasonable approach and must accept the fact that others may not have thought it through in quite the way we have. Who knows, they may be even be right on a point or two. It’s a characteristic of Berkshire shareholders to hear others out and consider points of disagreement dispassionately. Long term Berkshire shareholders may feel that it is our community but we should remember that the door is always open to new things and new members.

Conclusion

If you have read each section thoughtfully, you are fully qualified as a Berkshire shareholder. You don’t have to agree on every point. Berkshire investors are able to disagree amicably. Where they need to agree is on the basic points of liberal capitalism and the importance of integrity in business leadership. Berkshire shareholders are very much like all the best investors. They think carefully and act slowly. They don’t speculate and look for a quick buck and they don’t invest in things they don’t understand. If you are okay with these few points, you will likely have a very positive long term experience with Berkshire. Maybe we’ll meet you at this year’s capitalist Woodstock next May. As for timing, it’s almost always a good time to buy Berkshire. It was cheaper a couple of months ago at around $270 per B share, a price at which I recommended it in an earlier article, but it’s still okay trading around $310. I rate it a Strong Buy.

Be the first to comment