Kalinovskiy/iStock via Getty Images

Investment Overview

New Jersey-based Adma Biologics (NASDAQ:ADMA) looks to present an attractive investment opportunity at the present time – at least on some levels – but the downside risks are such that it’s tricky to fully back the upside opportunity.

In a recent corporate presentation the company describes itself as follows:

ADMA Biologics is an end-to-end commercial biopharmaceutical company committed to manufacturing, marketing and developing specialty plasma-derived products for the prevention and treatment of infectious diseases in the immune compromised and other patients at risk for infection

Adma’s revenues have been growing year-on-year – from just $1.1m in 2012, to $81m in FY21 – thanks to sales of its 3 FDA approved products, as follows:

- BIVIGAM – an Intravenous Immune Globulin (“IVIG”) product indicated for the treatment of Primary Humoral Immunodeficiency (“PI”), also known as Primary Immunodeficiency Disease (“PIDD”), was approved in 2019.

- ASCENIV (Immune Globulin Intravenous, Human – slra 10% Liquid), an IVIG product indicated for the treatment of PI, also approved in 2019.

- Nabi-HB (Hepatitis B Immune Globulin, Human), which is indicated for the treatment of acute exposure to blood containing Hepatitis B surface antigen (“HBsAg”) and other listed exposures to Hepatitis B

These three products – primarily BIVIGAM and ASCENIV – drove revenues of $33.9m in Q222 – up ~90% year-on-year, and a gross margin of 23%. For full year 2022, management has forecast for revenues of >$130m – up at least 60% year-on-year – with “continued gross profit expansion and narrowing net losses as 2022 progresses.”

Although the company generated a gross profit of $11.4m in H122, vs. ($2.72m) in the equivalent period last year, operating expenses totaled $35.4m, and as such, Adma made a loss from operations of $24m, and after interest expense of $8m and loss on extinguishment of debt of $6.7m are added on with some other additional expenses, the company returned a net loss of $38.8m.

In February last year, the activist investor Caligan Partners acquired a ~6% stake in Adma and immediately urged the company to consider either a strategic review or a sale – by September, Adma’s share price had sunk to an all-time low of ~$1.1. The growing revenues appear to be winning the market back over, however, since the share has risen by >100% since September.

Adma has a reasonably strong funding position – management reported working capital of $195m as of Q222 – and also has provided longer-term guidance, suggesting that it will generate >$250m revenues in 2024, and at least $300m or more thereafter. Just as importantly, or if not more importantly, it has stated:

ADMA continues to forecast achieving corporate gross margins in the range of 40-50% and net income margins in the range of 20-30%. These assumptions translate to potential annual gross profit and net income in the range of $100-150 million and $50-100 million, respectively, during the 2024-2025 time period and beyond.

This is the crux of the investment proposition around Adma in my view. Profitability is a must in the long term, because although revenues have been growing at the company, net income in 2019, 2020, and 2021 has been ($48m), ($76m), and ($72m), and when your peak revenue target is not much more than $300m, and your cash position <$200m, it’s difficult to see how the company avoids running into financial difficulties if there are any slip-ups.

Should management successfully rein in its losses, however, and start to deliver some profits for shareholders the market may begin to feel the company is worth more than its present market cap of $526m – you could just about make a case for a >$1bn market cap, in my view.

Let’s consider some of the fundamentals of Adma’s business to try to gain some insight into the chances of management meeting its targets.

The Plasma Collection Market and Adma’s Role In It

According to its corporate presentation, Adma is one of only six manufacturers in the US Immunoglobin (“IG’) market, and of those six, four – namely Grifols (GRFS), CSL Behring, Shire and Octopharma – control 94% of the market in the US.

According to Adma, this market is presently worth $9.5bn, but is estimated to be worth >$17bn by 2030, and with competitors “at or near capacity” Adma is expecting to increase its own market share to 1.5% – 2.5%.

The company operates six FDA licensed plasma collection facilities in the US, with two more facilities currently in operation and “under FDA licensing preparation and review”, and a further two under construction. According to Adma:

A typical plasma collection center, such as those operated by ADMA BioCenters, can collect approximately 30,000 to 50,000 liters of source plasma annually, which may be sold for different prices depending upon the type of plasma, quantity of purchase and market conditions at the time of sale.

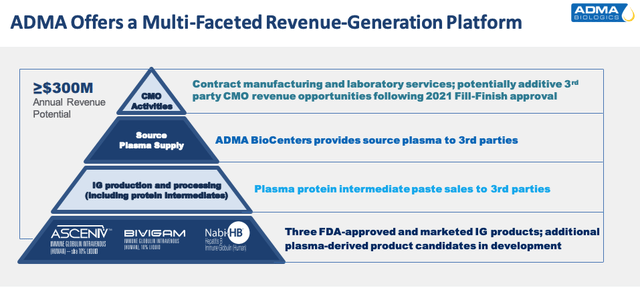

Adma makes its three commercialized products at its FDA-licensed, plasma fractionation and purification facility in Boca Raton, Fla., which has a peak processing capacity of 600k liters, and is valued by the company at ~$400m, based on management’s assessment of how long it would take – ~5 years – and how much it would cost to construct a center of equivalent value. The company breaks down its revenue-generating capacity as per the below diagram:

Adma revenue generation expectations (investor presentation)

Plasma derived therapeutics can be used to treat genetic and acquired diseases that affect “hundreds and thousands” of patients in the US, Adma estimates, but the process of collection is far from straightforward. Red and white blood cells contain ~55% plasma, which is itself 90% water, ~7% protein, and 3% other materials.

Of this 10% (protein and other materials), 60% is albumin, 15% IgG, 1% factor VIII (used for blood clotting) and 24% other types of protein. Centrifugation, fractionation, and filtration techniques – amongst others – are used to obtain the final product, in a process that apparently takes 7-12 months. This complexity helps to explain why there are only six manufacturers operating in the US today – barriers to entry certainly seem high.

Peak Revenue Opportunity

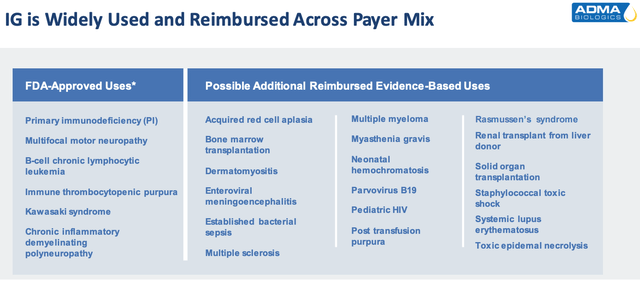

Adma estimated peak revenue opportunity (investor presentation)

As we can see above, IG is used to treat a number of diseases, and importantly, it’s eligible for reimbursement, meaning the government and health insurers will pay the lion’s share of a patient’s fees.

The list of label expansion opportunities provided by Adma in the slide above includes several illnesses that represent multi-billion dollar markets – Multiple Sclerosis (“MS”), Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (“SLE”), and multiple myeloma (“MM’) for example, although the role that plasma can play in treating these diseases may be minimal.

The expansion of Adma’s customer base for both BIVIGA and ASCENIV has underpinned some impressive revenue growth, with management noting in its Q222 earnings press release that it was:

particularly encouraged with the continued physician adoption and utilization of its proprietary IVIG product, ASCENIV. We believe that leading product demand indicators continue to support durable and sustained upside for this product, with possible upside to peak potential.

That’s certainly encouraging, as is the promise of net income of $50 – $100m – a profit of $75m, for example, would imply a forward price to earnings ratio of ~7x, which is an attractive prospect, given that generally, a PE ratio <20x suggests that a stock price has upside potential.

The Primary Immunodeficiency market is estimated to reach a market value of ~$10bn per annum by 2030, so theoretically at least, Adma would only require a 3% share of this market to achieve its revenue goals, and presumably, its profitability goals.

My suspicion would be that Adma will need to develop one of two more products however since the list of companies treating PID is extensive and includes Baxter (BAX), Bayer AG, Astellas Pharma, Biocon, Grifols, and other besides.

In its pivotal trial, ASCENIV achieved zero hospitalisations due to infection in its patients population and management believes there could be more approvals in store for the therapy, in HSCT / bone marrow transplant – a population of ~22k, solid organ transplant – population of ~22k, and perhaps in cancer patients receiving chemotherapy – ~$650k patients per annum.

In Search Of Profitability

I would broadly agree with management that ASCENIV, in particular, could help Adma achieve peak revenues of ~$300m per annum within three years, although this goal actually strikes me as somewhat unambitious based on the market research available.

A cap of $300m peak revenues does limit the upside opportunity, although if we assume a price to sales ratio of ~5x is acceptable for a profitable company, you could make the case for Adma’s market cap valuation being as high as $1.5bn, implying a potential return on investment of nearly 200%.

Revenues are nothing without profitability, however, and this is another area of uncertainty for Adma. Losses from operation in H122 did not shrink by much year-on-year – they fell from $31m, to $24m – and at that rate, not only does profitability by 2024 look questionable, it brings into a play a much more negative scenario in which Adma runs out of funding.

That prospect – and of investors being diluted by further fundraising, could bring an end to Adma stock’s recent bull run and send the stock price back down toward $1 again.

How does the company narrow its losses? My suspicion is that plasma is not a high margin business – if it were, then why is the sector largely overlooked by the big pharma?

When you consider the moving parts – finding and paying donors, engineering the plasma, and converting it into therapies approved for commercial sale – it strikes me as a time consuming and difficult business where several things can potentially go wrong. Safety is of paramount importance, which makes equipment expensive, and regulatory oversight strict.

In Adma’s case, while the company has done well to commercialize two therapies, they’re both indicated to treat the same condition, as are ~10 other therapies.

When it comes to label expansion, my guess would be that the efficacy of plasma derived products may not be of a quite high enough standard – and with a heightened safety concern – to see it establish a foothold in a market such as multiple myeloma, or as an adjunct to chemotherapy, for example. These markets are intensely competitive and the number of different approaches beside blood plasma to treating them is significant.

Conclusion – Adma Makes A Case For Growth and Even Triple-Digit Upside But The Risks Must Be Acknowledged

In this post I have tried to provide an overview of what Adma does – harvests plasma and uses it to make three FDA approved products with peak sales capacity of ~$300m, how it’s performing – growing revenues close to a triple-digit year-on-year percentage, but making heavy losses that could exhaust funding if there is not a drastic improvement, and where it’s headed – according to management, to its peak revenue target, plus profitability, with several new markets in play.

After a dismal year in 2021, in which net losses exceeded $70m for the second year running, Adma’s share price fell to an all-time low, while activist investors called for a strategic overhaul or sale of the business. Finally, the share price is picking up again as revenues grow – but which way will it trend longer term?

As I have mentioned, in management’s optimal case scenario, where peak revenues reach $300 and profits reach $50 – $100m, I can make a case for a valuation of the business that climbs just above $1bn, when we consider that peak profitability is capped at ~$100m, and after applying an additional risk related discount.

Of course, such a scenario is both plausible, and very attractive for investors, but what gives me pause for thought is the niche market, which has high barriers to entry but is also expensive, time consuming, and not generally associated with high margins, or breakthrough treatments. Blood plasma was memorably given an emergency use authorization to treat COVID related illness in the early days of the pandemic, before authorization was withdrawn when it was shown the use of convalescent plasma has no effect on patients.

It may interest prospective investors to note that plasma giant Grifols, for example, has seen its share price decline by 72% over the past five years, and by 55% over the past 12 months. The company’s market cap valuation is $4.9bn at the time of writing, and it generated $5.6bn revenues last year, suggesting that Adma’s business could grow significantly larger over time.

The issue is however that Grifols made a net profit of just $208m last year – the company has 300 plasma donor centers, to Adma’s 10, yet still struggles to turn a meaningful profit.

Although I can see plenty of positives and potential tailwinds for Adma, the tricky nature of the plasma collection business and its fundamental unprofitability – and underperformance of sector company’s share prices – makes me hesitant to back Adma outright for high levels of growth or profitability at the present time.

The business looks a little undervalued, but equally, the margins look a little too tight, implying a higher level of risk to any investment.

Be the first to comment