mrgao/iStock via Getty Images

[The intelligent investor] will do better if he forgets about the stock market and pays attention to his dividend returns and to the operating results of his companies. -Benjamin Graham

Leaving The Cult Of “Beating The Market”

One of the most pervasive pieces of advice given about investing in dividend stocks is: It is better to invest for total returns than high income.

This advice is well-intentioned, clearly given to help (mostly newer) investors avoid yield traps, or “sucker yields” – stocks that offer high dividend yields that are at high risk of being cut due to a crummy business model, high payout ratio, overleveraged balance sheet, poor management, etc.

I of course agree that investors should be very careful with any high-yielding stock. Many investors have been burned by buying risky, weak stocks yielding 8%, 9%, or higher primarily because of the yield.

Likewise, even if the dividend is not cut, high yields often convey the market’s collective belief that a company has weak growth prospects or eroding fundamentals. If the market is correct (and usually the market at least has a decent point), then most if not all of one’s total return will be the dividend yield. In these cases, the stock price typically remains rangebound at best or drops at worse. So, one is essentially trading any potential capital gains for dividend income.

Again, I agree that this form of investing is inadvisable. But that does not necessarily mean one should invest for maximum total returns instead.

The goal of seemingly every investment fund, ETF, and individual stock is to “beat the market” in terms of total returns. On Wall Street, this is the most popular goal to pursue and the most vaunted achievement, for those precious few who have attained it over a long period of time.

Don’t get me wrong. Trying to achieve maximum total returns is a fine way to invest. It’s a worthy goal. But not every investor needs to invest that way. It is not the only worthy investment goal one can pursue. Rather, in the words of Master Yoda from Star Wars: “There is another.”

That other worthy investment goal is what I call “income growth.” As I explained in “Death of a Capitalist“:

[M]y goal is not and has never been to generate maximum or market-beating total returns. Rather, my twofold goal has been to:

- Generate more dividend income than the broader market, and

- Achieve faster portfolio-wide dividend growth than the market.

In a sense, my goal is to beat the market, but not necessarily on total returns. Rather, I want to do better than the market when it comes to income generation, both now and into the future.

Finding stocks that generate above-average yields is the easy part. The hard part is finding stocks with above-average yields and good prospects for strong dividend growth into the future. This requires research and analysis in order to form a forward-looking thesis.

Invest Like A Landlord

In my mind, “dividend growth investing” (or “DGI”) is named as such precisely because of the focus on dividends. For all practical purposes, it ignores total returns and focuses on dividend safety and dividend growth, which is basically another way of saying that it focuses on strong and reliable businesses that pay a dividend and want to increase that dividend along with their earnings over time.

As the father of value investing, Benjamin Graham, essentially advised: Pay attention to company operations and dividends, and let total returns take care of themselves.

This is what I mean when I talk about investing with the mindset of a landlord. Does the landlord of a rental property constantly look for the market value of his property to know when to sell for maximum total returns? No. The landlord focuses on managing the property in such a way as to generate higher rental income over time. All else being equal, higher rental income should translate into a higher market value of the property.

Dividend growth investors should view stock investments fundamentally the same way: Focus on generating a growing dividend income stream, and the market values of their stocks should follow. In other words, let total returns take care of themselves.

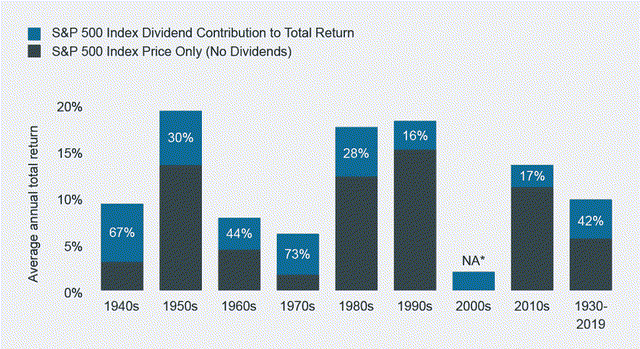

After all, it’s useful to remember that, over long periods of time and especially during periods of economic disruption, dividends make up a large portion of the stock market’s total returns.

From 1930 through 2019, dividends contributed 42% of the S&P 500’s (SPY) total returns.

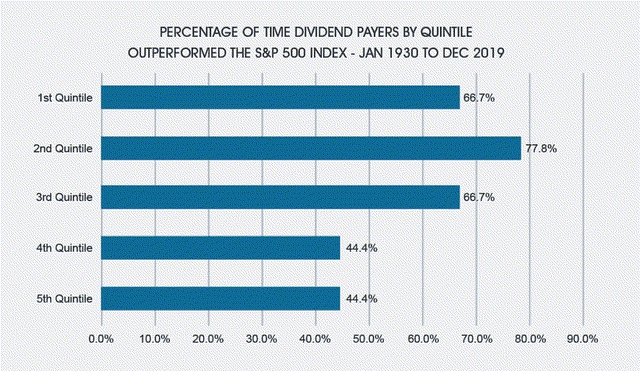

Moreover, during the same 90-year time period, higher-yielding stocks tended to outperform the market two-thirds of the time or more. In the chart below, we find dividend payers broken out by quintile, with the 1st quintile being the highest yielders and the 5th quintile being the lowest yielders and non-dividend-paying stocks.

The best performers in the long term tend to be the companies with a relatively high yield but not the highest yields.

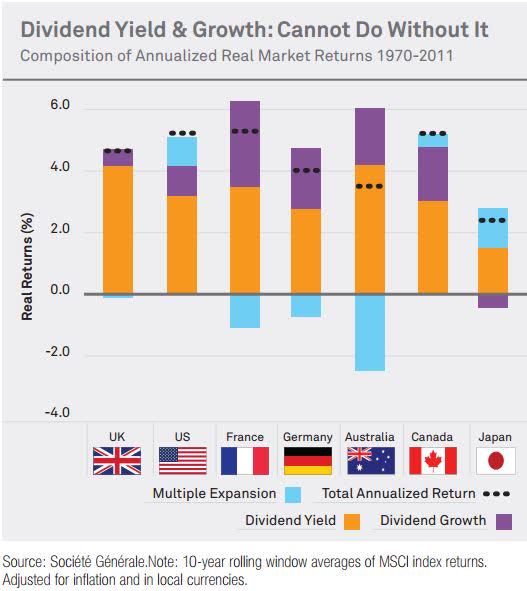

Interestingly, during the period from 1970 to 2011, the combination of dividend yield and dividend growth played a much larger role than multiple expansion in contributing the real (inflation adjusted) returns in developed countries around the world:

BlackRock via Simply Safe Dividends

Earnings growth, which is approximated above by dividend growth (purple), is often less impressive when adjusted for inflation. That makes the dividend yield even more important as a component of total returns.

Of course, as previously stated, the explicit goal is not total returns but rather a safe and reliably growing dividend income stream. But investors who have focused on this alternative goal have historically produced quite attractive total returns as a byproduct.

Objection: The “Free Dividends Fallacy”

One common objection that dividend investors hear is that the stock price always drops by the exact amount of the dividend payout, and thus investors are no better or worse off if a company pays a dividend. In fact, they are probably worse off because the stock has shed some of its share price and the company now has less cash to reinvest in the business.

In their 2016 paper, “The Dividend Disconnect,” Samuel Hartzmark and David Solomon argue that most investors overlook this fact, believing that a dividend is like a bond coupon (which does not reduce the value of the bond) when all it really does is shift shareholder returns from the stock price to the cash dividend payout.

Hartzmark and Solomon call this the “free dividend fallacy.”

The takeaway from the “free dividend fallacy,” according to those who cite it as an objection to DGI, is that investors should be indifferent to whether a company pays a dividend. In fact, they say, since dividends are taxed, investors would be better off actively avoiding dividend-paying stocks.

This objection is utter and complete baloney. Malarkey. Nonsense.

The long-term outperformance of dividend payers is proof that the “free dividends fallacy” objection is wrongheaded.

There is a crucial difference between a stock price automatically dipping by the amount of the dividend (which stock exchanges do in order to prevent traders from buying a stock on the ex-dividend date, selling the next day, and pocketing the dividend) and the underlying business’s intrinsic value.

Like a landlord receiving a rent payment, a shareholder receiving a dividend does nothing to alter the intrinsic value of the asset. If you think about this for more than two consecutive seconds, it is obvious.

- Does receiving a dividend from Coca-Cola (KO) make the Coke brand any less valuable?

- Does receiving a dividend from Simon Property Group (SPG) make its portfolio of high-end malls less valuable?

- Does receiving a dividend from Verizon (VZ) mean that fewer people are paying their cell phone bills?

- Does receiving a distribution from an oil & gas pipeline giant like Enterprise Products Partners (EPD) decrease the value of its long-term contracts?

The answer to all of these questions is obviously “no.”

The only conceivable way that a dividend reduces the value of a company is by reducing cash on the balance sheet. But, again, this does not reduce the intrinsic value of the business. It just transfers cash from the company to the shareholder.

It would be like a landlord who holds a rental property in an LLC taking a distribution from the LLC by transferring idle cash from the LLC’s bank account to his/her personal bank account. Yes, from an accounting standpoint, this reduces the total asset value of the LLC. But does it mean that the landlord is financially worse off because of it? No.

Again: Pay attention to the operations of the business and to your dividend income and let the gyrations and fluctuations of stock prices take care of themselves.

Three Examples of DGI In Action

My two longest held stocks are both real estate investment trusts (“REITs”) specializing in net lease properties, wherein tenants are responsible for most if not all property maintenance, insurance, and taxes. The REITs are Realty Income (O) and National Retail Properties (NNN).

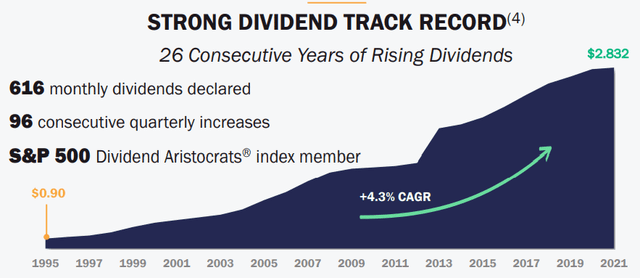

These two REITs are ideal investments for the DGIer. Not only do they have above-average dividend yields, but they also boast impressive dividend growth track records. By managing to grow their dividends even through recessions, when the broader market’s dividend is declining, they have managed to put up impressive dividend growth metrics compared to the S&P 500.

Here’s O’s dividend growth record, spanning 26 consecutive years:

Realty Income Q3 2021 Presentation

Here is O’s total dividend growth from 1995 through 2021 compared to that of the S&P 500:

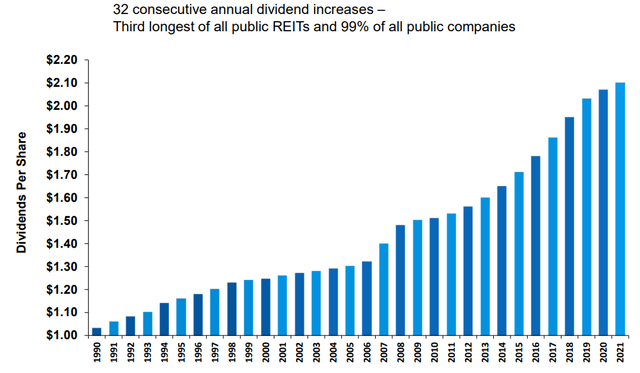

And here’s NNN’s dividend growth record, spanning 32 consecutive years:

National Retail Properties Q3 2021 Presentation

NNN has established itself as a conservative grower, managing its portfolio and balance sheet for maximum safety and reliability. But that has meant a slight underperformance in terms of long-term dividend growth. Here is NNN’s total dividend growth from 1990 through 2021 compared to the S&P 500:

I don’t mind this long-term dividend growth underperformance, because the DGIer’s performance, in my estimation, ought to be measured on a portfolio-wide basis. After all, how is it fair to measure the performance of one stock in a DGIer’s portfolio against Standard & Poor’s entire portfolio of 500 stocks?

Some of one’s holdings provide higher yield but slower growth, while others provide less yield but higher growth. Some holdings tilt toward safety and consistency, while others tilt toward rapid growth.

It’s a balancing act.

Besides, even if some holdings in one’s portfolio are experiencing slower growth, one can always refresh the portfolio with new names that offer faster growth.

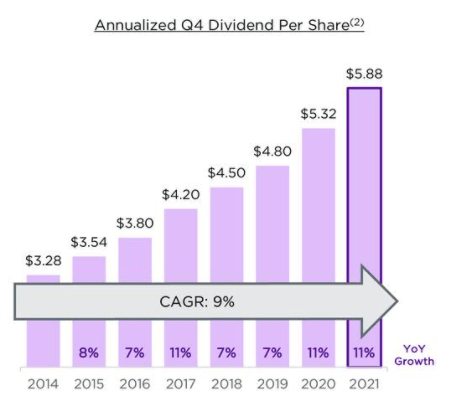

In a recent article, I highlighted cell tower REIT Crown Castle International (CCI) as a fast-growing dividend-payer. It is quickly becoming a large holding of mine.

Crown Castle 2021 Presentation

Here’s CCI’s total dividend growth from 2014 through 2021 compared to that of the S&P 500:

Where NNN excels in yield, CCI excels in dividend growth. Opposites attract.

Bottom Line

The real reason I (and many other DGIers, I imagine) don’t invest for total returns is that it requires selling the stock.

Ideally, I’d like to someday retire or semi-retire without needing to sell stocks in order to fund my lifestyle. The growing income stream provided by DGI affords the ability to fund one’s living expenses without the need to draw down one’s share count and proportionate ownership of the underlying businesses. That’s the beauty of it.

Though DGIers shouldn’t get too dogmatic about not selling, I do believe it’s a good idea to buy companies that one could envision holding forever (or at least until death; I have heard you can’t take your stock certificates with you when you die).

This “buy-and-hold-forever” mindset is the primary reason why some investors, like me, leave the “beat the market” cult and instead invest like a landlord, focused on creating a large, sustainable, and growing income stream.

Be the first to comment