Douglas Rissing/iStock via Getty Images Economic Changes In High Inflation And Low Inflation (Dr. Bill Conerly, based on data from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis)

The Federal Reserve will take strong efforts to lower inflation, but not primarily to help consumers today. Some of their statements mention the pain caused by prices rising faster than wages, but their strong action comes from a belief that failure to bring inflation down now will result in much more persistent inflation, with more business cycles in the years to come.

Some statements by the Fed’s policy team sound like politicians’ simplistic interpretations arguing that it hurts poor people the most, and that’s the problem.

This argument ignores the potential for wage inflation and higher transfer payments to offset rising consumer prices. And thus, it ignores the reasoning that is really driving the Fed’s anti-inflation policy.

The first point in the Fed’s logic is that the public’s inflation expectations play a large role in actual inflation. The simple explanation is that if people throughout the economy expect high inflation, then businesses will push their prices higher, while workers will demand greater wages. These actions will add to inflation. This commonsense explanation is bolstered by sophisticated econometric models that reach the same conclusion.

The theory and practice of using inflation expectations in economic models is described by Loretta J. Mester, President of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, with an interesting conclusion. Economists call expectations “anchored” when they match the Fed’s target. When the public expects higher inflation, then expectations are not anchored. Mester asked, “… which situation would be more costly: erroneously assuming longer-term inflation expectations are well anchored at the level consistent with price stability when, in fact, they are not? Or erroneously assuming that they are moving with economic conditions when they are actually anchored? Simulations of the Board’s FRB/US model suggest that the more costly error is assuming inflation expectations are anchored when they are not.”

The costs of the first error would be the large economic contraction that would be needed if inflation expectations became unanchored to the Fed’s target. The cost of the second error is the economic contraction needlessly undertaken.

In 2021, when the first signs of inflation were rising, the Fed believed that their public statements would be enough to keep inflation expectations in check. At the end of the year, Jerome Powell predicted “inflation will move down significantly” and reiterated the Fed’s commitment to price stability. Reality, however, persuaded most people that inflation was rising regardless of the Fed’s pronouncements. Since then, the Fed has come to understand that action is necessary, not just words.

Why is the Fed so committed to low inflation? Their talk about harm to consumers is posturing, because inflation will eventually boost wages, and governments can increase transfer payments. In fact, many benefits automatically adjust for inflation. The great reason for the Fed’s commitment is volatility.

Powell recently said, “… restoring price stability is just something that we have to do. There, there isn’t an option to fail to do that because that is the thing that enables you to have a strong labor market over time. Without restoring price stability, you won’t be able, over the medium and longer term, to actually have… a sustained period of very strong labor market conditions.”

Federal Reserve governor Michelle Bowman echoed this sentiment, saying that inflation risks “a prolonged period of economic weakness coupled with high inflation, like we experienced in the 1970s.”

James Bullard, president of the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, noted about 1970s, “The real economy was also volatile during this process.”

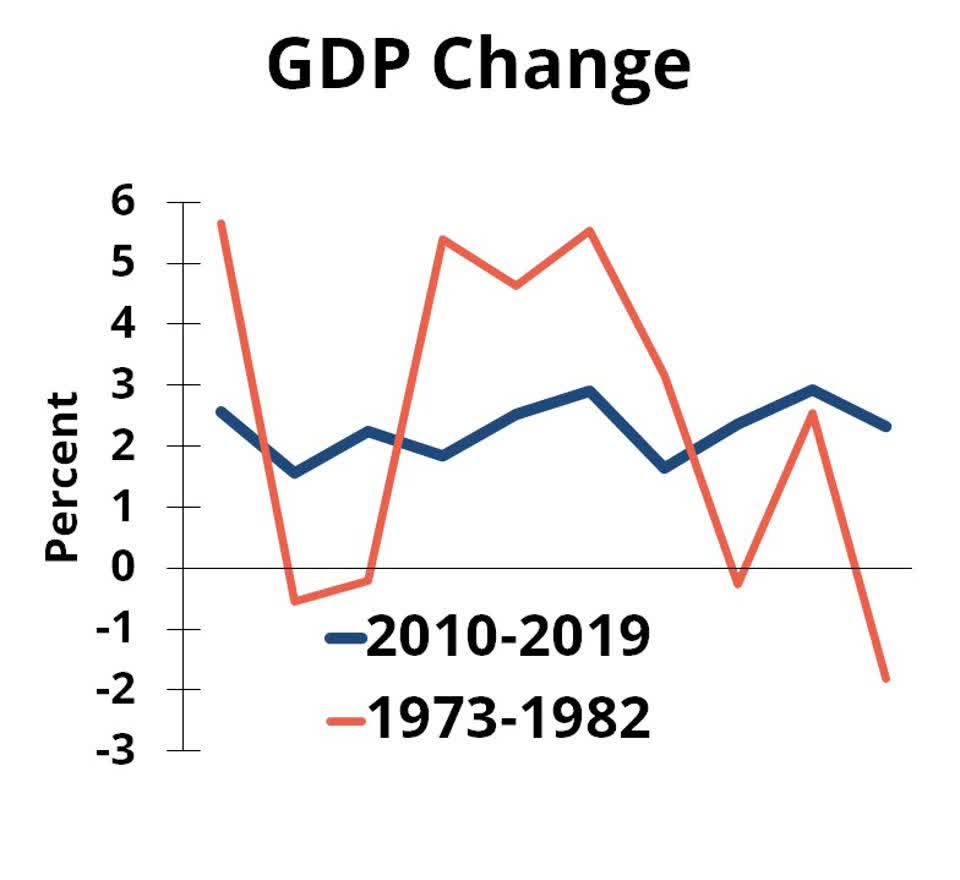

That’s the crux of the issue. Economies with high inflation tend to be very cyclical, with booms punctuated by busts. Economies with low inflation tend to be much more stable, with fairly steady growth. The chart at the top of this article displays one instance of that stark reality. In the 2010s, inflation averaged two percent and the economy was much more stable than the nine-percent-inflation 1970s. This patterns show up both in U.S. economic history and in international comparisons.

So here’s the logical chain for Federal Reserve policy: First, high inflation is bad for the real economy: jobs, production and income. Second, letting inflation expectations rise makes it more costly to bring inflation down. And third, actual inflation has to stay low at least most of the time to keep those inflation expectations low.

In past articles, I expressed skepticism that the Fed would do this job. There’s still doubt about how they will react a year from now when employment starts to suffer. The evidence from the Fed’s actions and their statements so far is that they will, most likely, stay firm. They understand that long-run prosperity for the American people requires low inflation.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment