robertcicchetti/iStock Editorial via Getty Images

If society understood the hotdog vendor problem at a more visceral level, both the 2000 tech bubble and the 2021 tech bubble could have been avoided.

The hotdog vendor problem is microeconomics which gets completely overlooked relative to its sister discipline, macroeconomics (Interest rates, government spending, the Fed).

A dearth of economic knowledge

A handful of academic pursuits have long been falsely labeled as the “boring classes”. Math is the classic example, but I think other supremely useful disciplines like engineering and economics have been similarly maligned.

These labels led to society as a whole not engaging with these fields to the extent that it should and so there was this huge push to encourage kids to go into STEM (science technology engineering mathematics). The STEM initiative has been quite successful at driving increased participation in these fields.

Economics, however, is not included in the STEM initiative and got left behind. At a societal level it is woefully understudied and the effects of that are readily visible in the way the market values stocks. In fact, I posit that with proper economic knowledge, it would have been broadly obvious that tech was egregiously overvalued in 2000 and 2021. So rather than the euphoric spike and subsequent crash, tech would have just traded at a reasonable value consistently through those time periods in my view.

The Hotdog Vendor Problem

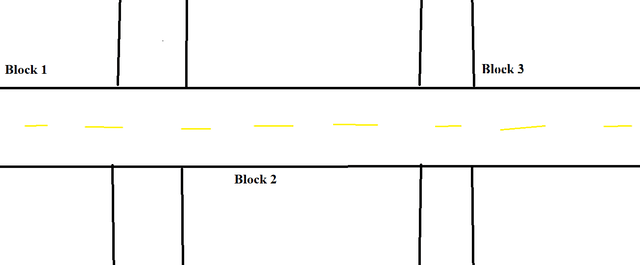

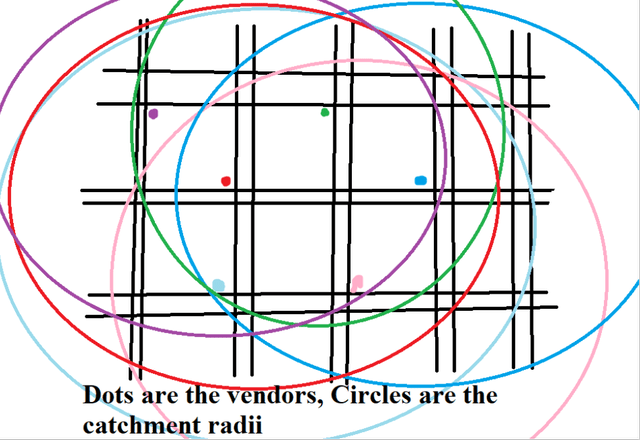

Picture a busy New York City street. For the sake of simplicity we are limiting the universe to 3 blocks of street. Forgive my shoddy artwork, but for illustrative purposes it looks like the below.

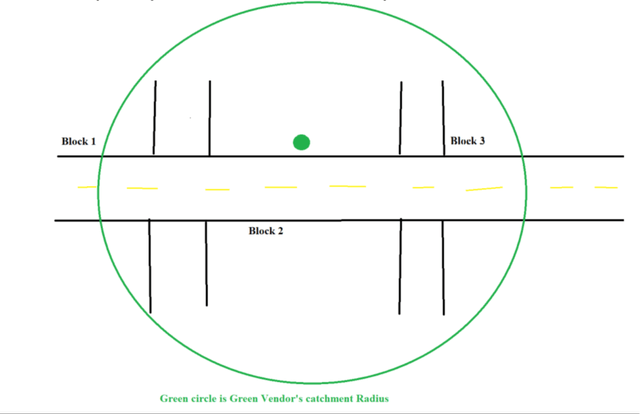

A hotdog vendor has a catchment radius of roughly 1 city block (diameter of 2 blocks). Where should they position to maximize profits?

A single vendor positioned in the middle would maximize its profits. Its catchment radius would cover the entirety of block 2 along with parts of blocks 1 and 3.

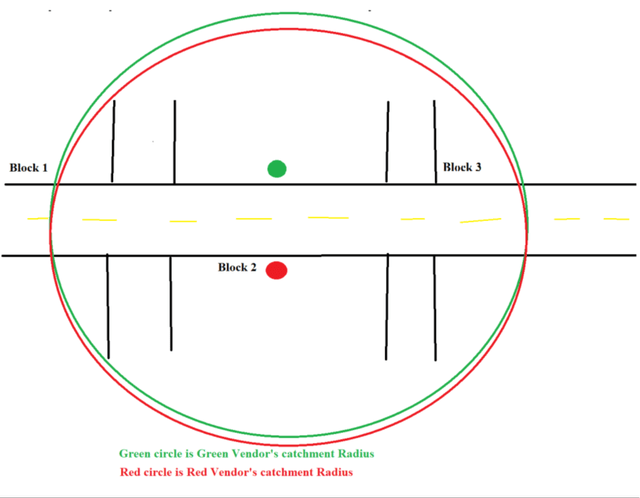

But what happens if there are 2 vendors?

That is not so good. Customers will see both stands and go to whichever is cheaper so there would be a price war and the profits of both vendors would suffer.

Overlapped catchment area is significantly less profitable than monopolistic catchment area. So where would 2 economically rational vendors place their stands?

This gets into some complex game theory in which a variety of factors matter

- Gross profit margins on monopolistic sales relative to gross margins on competitive sales

- Which vendor chooses location first or at the same time

- How elastic buyers are to price points and how far they are willing to divert their travel to save a buck

- You get the point

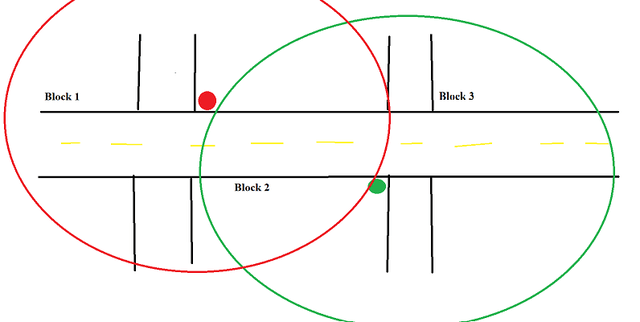

Eventually it arrives at something called a Nash Equilibrium in which neither vendor can improve their profits by unilaterally changing their location. That would look something like this:

There is still some overlap in which there is pricing competition, but the monopolistic areas are large enough that each vendor is still incentivized to keep their prices somewhat high. If Green vendor cut their prices significantly they might be able to get the majority of customers from the overlapping catchment area, but they would lose significant margins on their monopolistic area such that overall it is likely not worth it.

Now that we understand the basic logic of the hotdog vendor problem, I want to explore how that logic got overlooked in the tech bubbles.

Myopic focus on TAM

Pet supplies had already been sold in retail stores for decades before Pets.com came along. The key innovation here was that by selling pet supplies online they could increase the catchment radius from the maybe 15 mile radius of a store to essentially the entire U.S. and eventually the world.

This is a similar story to most of the dot com bubble stocks. It represented a massive increase to total addressable market or TAM. Rather than selling to a few thousand customers, the dot com companies suddenly had the ability to sell to everyone. TAM went up by an order of magnitude.

While it is indeed a powerful concept, the math on profitability was misunderstood. The market used simple extrapolation:

“If a single store serving a radius of 15 miles generates a certain amount of profit, then an online store serving 100X the area will generate 100X the profits.”

Missing from this infatuation with TAM is the simple logic of the hotdog vendor problem.

Consider a similar increase to TAM for the hotdog vendors. Let’s say for example that the vendors have people with bicycles delivering hotdogs ordered via an app. Now instead of a 1 block catchment radius, the vendors have 5 block catchment radii.

For the sake of simplicity, we shall ignore the costs of delivery so as to isolate the competitive aspects.

Now the diagram looks like this.

Not only do the 2 vendors from the original problem now have entirely overlapping circles, but they also have to compete with additional vendors from different blocks.

The hotdog apps from which people order would show price and the lowest priced hotdog would capture most of the customers.

It would swiftly become a race to the bottom. Profit margins drop until the vendors make just enough return to get by.

Thus, this innovation which was touted as increasing the TAM of the vendors actually ended up hurting the vendors and helping the customers. Anything that increases competition among suppliers is likely going to be good for customers and bad for suppliers.

Applying this to the tech stocks:

What was initially celebrated as a dramatic increase to TAM was later found out to be a massive increase to competition. Rather than competing with other nearby stores of the same category suppliers now had to compete globally.

The same thing happened in the more recent tech bubble. Quite a few subareas within tech became egregiously overvalued, but for the sake of this article I will focus on streaming.

Much like the dot come era, there were multiple innovations in streaming that were initially touted as TAM magnifying that later proved to primarily benefit customers at the expense of the industry.

- Movie rentals (Blockbuster) became order by mail – Netflix (NFLX)

- Order by mail became streaming online

- Linear TV became on-demand TV – Disney (DIS) cable channel becomes Disney +

Collectively, these innovations have been wonderful for consumers and destroyed the industry profit. Today, one can get unlimited content for a low price and at the same time the amount of money spent to produce that content is around an all-time high. Customers are quite literally getting more for less.

It used to be that a sitcom would only compete with other sitcoms that aired at the same time. It may not have been the best show, but it only needed to be the best show that played at the 8:30 Wednesday time slot.

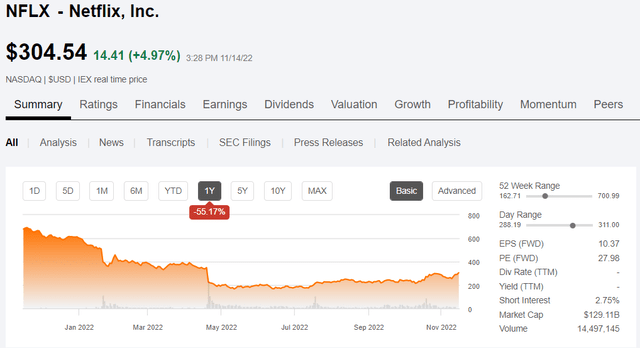

Now, every bit of content competes with an entire library of content, both current and historic. Netflix is by far the most successful streamer and has reached a point of decent profitability, but even it has collapsed from the dazzling prices of 2021

The moral of the story

When TAM increases, competition increases along with it. A bigger TAM is not necessarily a good thing.

Be the first to comment