shaunl

The U.S. Housing Market Bubble Is Popping

Speaking from the Brookings Institution a couple of weeks ago, Fed Chair Jerome Powell covered a wide-ranging variety of monetary policy topics. The speech was less hawkish than feared, and the stock market cheered when he failed to push back on the recent rally. But what was less widely reported at the time was Powell’s thoughts on the housing market. Specifically, Powell openly said that the U.S. housing market pandemic boom was a “bubble” and that the housing market is now going through the “other side of that”. Due to how much their words can move the markets, Fed speakers are known for almost comical amounts of euphemism in their speeches and interviews. But for the Fed chair to admit that the pandemic housing boom was a bubble that is now popping really has no precedent.

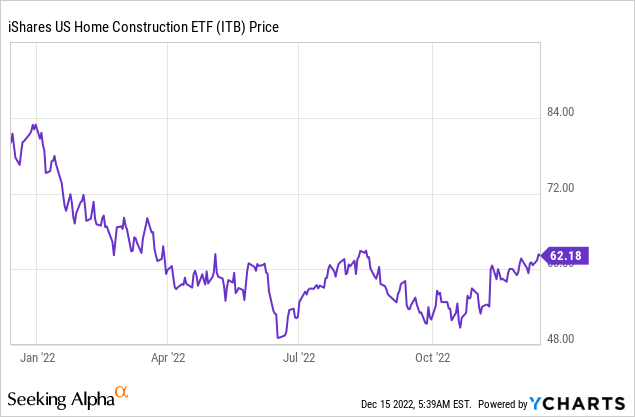

If you read between the lines, the words of Fed speakers this year tell you even more- they’re likely happy that home prices are beginning to fall back to fair value. But investors in homebuilders are partying like it’s 2006, with the iShares U.S. Home Construction ETF (BATS:ITB) nearly cutting its YTD losses in half since the October lows, and the SPDR Homebuilders ETF (NYSEARCA:XHB) not far behind. Of course, homebuilders have some of the lowest PE ratios in the market, but if their earnings turn to losses with the housing bust, then investors won’t be happy. And with the FOMC meeting this week bringing a 50 bps hike and indicating the Fed’s intentions to keep rates higher for longer, it’s clear to me that the Fed’s policies are designed to throw cold water on the housing market.

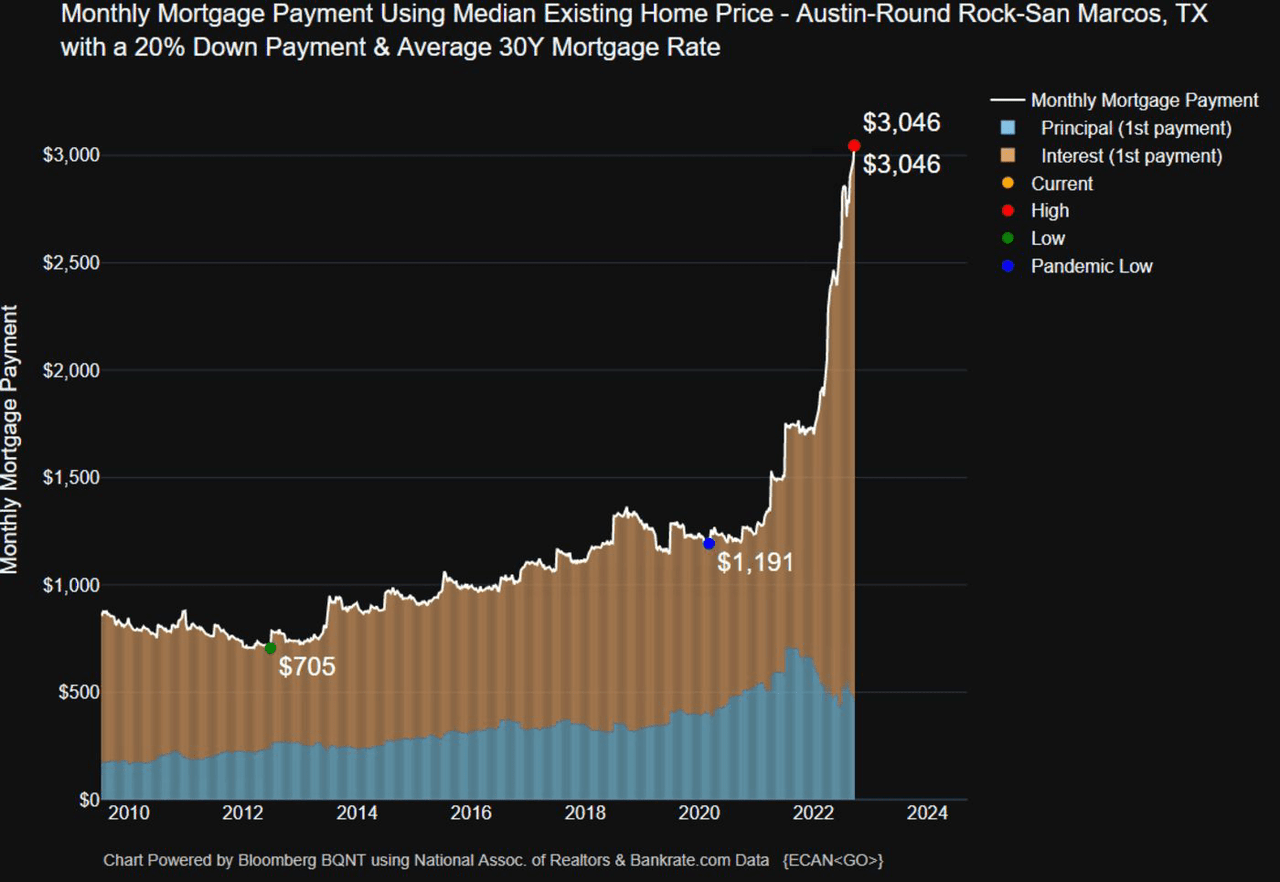

The math for homebuyers is sketchy. For a buyer looking to buy the median home with a 20% down mortgage, they’ve seen an unprecedented rise in the monthly payment they would be required to make over the last 2 years because of:

1. Massive home price increases

2. Mortgage rates more than doubling

For example, this is the situation (credit to Bloomberg) for the Austin, Texas metro as of this fall. The typical payment went from about $1,200 to $1,300 in 2019 to $3,000 to $3,100 now. But is this in line with economic fundamentals?

Austin Mortgage Payment on Purchase (Bloomberg)

Probably not. The job market in Austin has done well – as far as I can gather the median income is up a solid 20% or so since pre-Covid – largely due to the boom in tech companies moving people there from California. But 20% is a lot less than 2.55x, which is how much more expensive mortgage payments have gotten. Of course, Austin proper has gotten very built up, but this data includes Austin’s far-flung suburbs, many of which are mostly farm/ranch land.

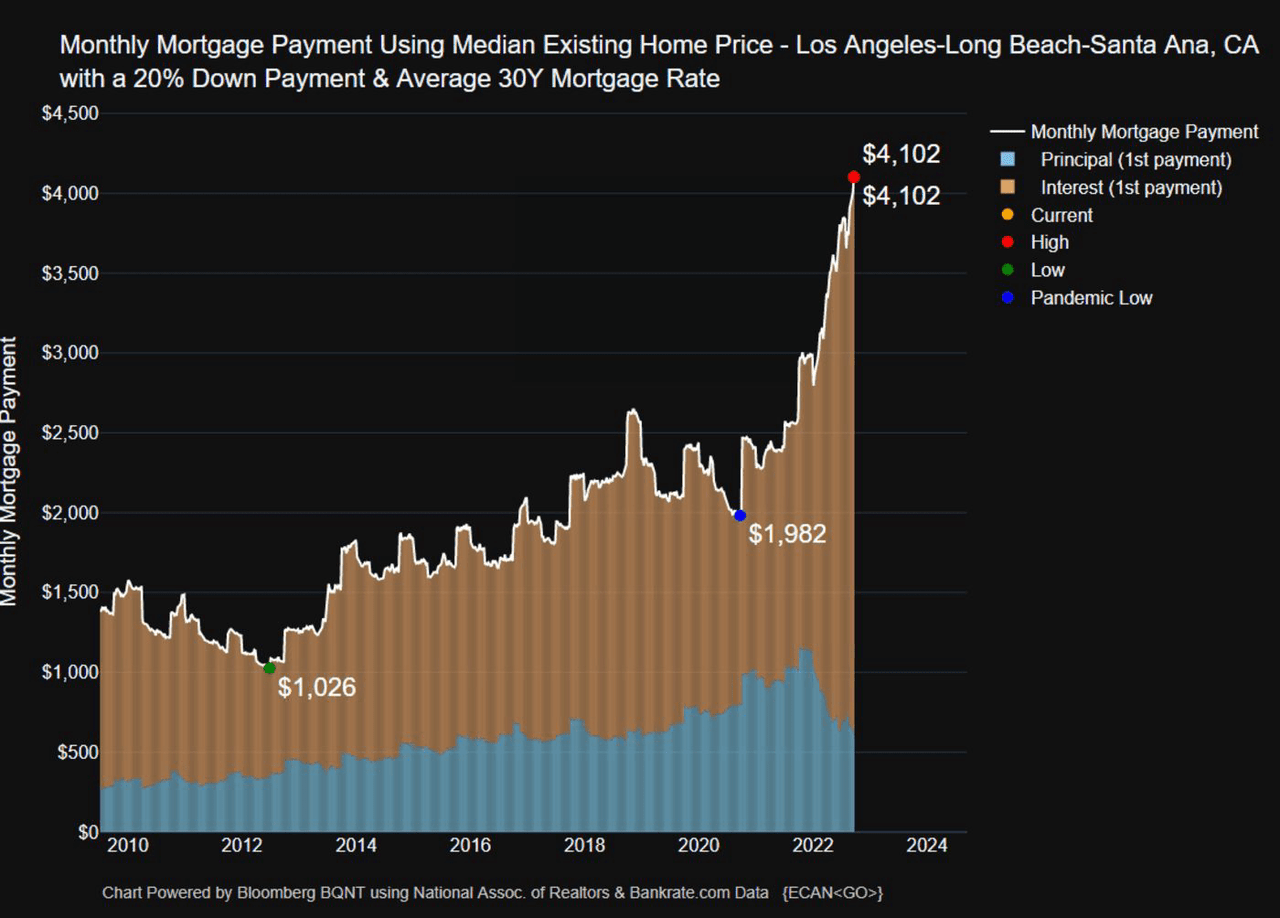

This is the situation for Los Angeles, which in contrast to Austin has lost population since the pandemic (ignore the principal vs. interest breakdowns, it’s a quirk of the amortization process).

Los Angeles Mortgage Payment on Purchase (Bloomberg)

This isn’t sustainable. There are few long-term constraints to supply in Austin, and Los Angeles is losing population outright. Why should the typical mortgage payment double if the city is losing population? It shouldn’t. For these reasons, most potential homebuyers are running the numbers at sellers’ asking prices and the numbers don’t work, so they’re not buying. Demand has fallen off of a cliff because people aren’t dumb – they don’t want to saddle themselves with huge mortgage payments by buying into a bubble.

Despite a brief uptick in the last week, mortgage applications have relentlessly declined this year because the math doesn’t make any sense for buyers, who have seen their wages somewhere between flat and up 20% or so since the pandemic, while the payments they’d have to make on buying a house have doubled or more. The only ways this can resolve are if rates go back to generational lows (not likely with the Fed’s higher-for-longer policy), or if home prices fall back to 2019 levels (already happening).

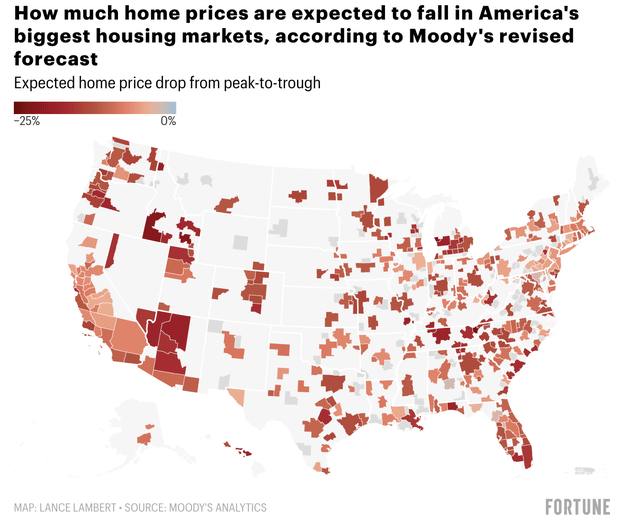

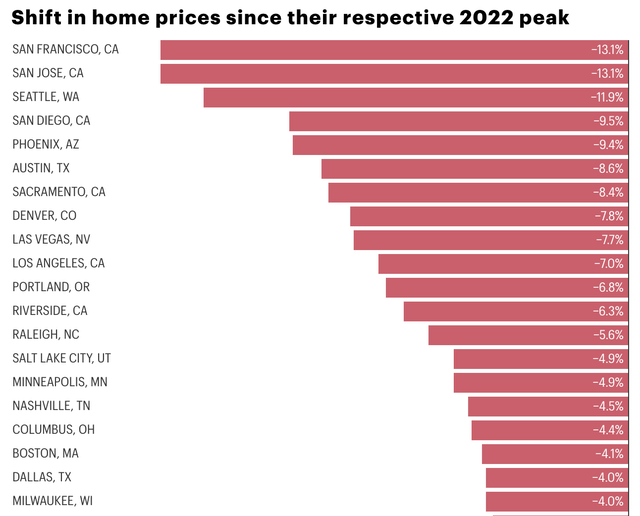

Lo and behold, excellent data from Fortune shows that prices are rapidly falling as buyers can’t or won’t pay bubble prices anymore. In many cases, they can’t even if they wanted to, because they no longer qualify for a large enough mortgage. The housing bust began on the West Coast and in Texas, and month by month has spread further and further east. And the U.S. declines barely hold a candle to other countries with out-of-control bubbles, such as Canada, Australia, and New Zealand.

Powell pointed to a longer-term housing shortage in his speech that needed to be fixed by increased supply in the long run. But is he right that supply can’t keep up with demand because of NIMBY homeowners and zoning boards? Research says maybe not.

There is a shortage of affordable housing in the U.S. and in most other English-speaking countries in the world. However, my data shows that supply surprisingly has kept up with demographics in the US. What it hasn’t done is keep up with speculative demand from flippers, I-buyers, second/third homeowners, and speculators. But with all of these players looking to exit the market before the bust, prices could easily fall as fast as they rose, because they’re not being bought as homes in many cases, but rather as speculative assets. The Case-Shiller index famously lags the reality on the ground in the housing market, but the early read on the declines is staggering, exceeding the early 1990s real estate bust in a matter of months.

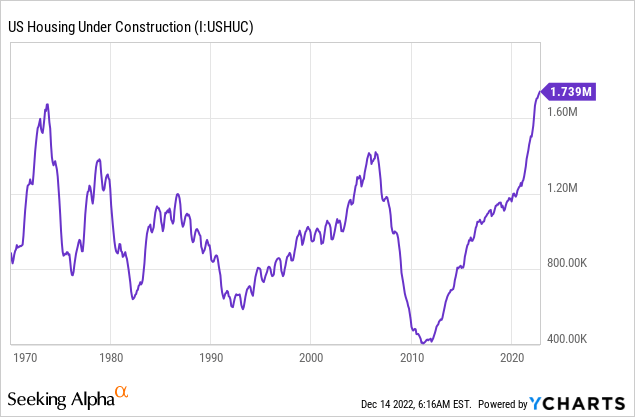

This comes just as homebuilders finally are finishing 1.7 million homes that they started construction on in 2021 at the height of the boom- the most ever for the US.

Who is going to buy these homes? Or the 100,000+ homes being added to the pipeline each month via housing starts? With mortgage rates still in the 6-7% range, prices near COVID highs, and population growth effectively zero from now on due to declining life expectancy and the opiate crisis, I’m not sure who will. Homebuilder Lennar (LEN) offloaded some subdivisions to rental companies, while reports are in that the cancellation rate for Texas is now 39% for homebuilder buyers. They’re now looking to sell about 5,000 homes to institutional investors in one chunk. The problem is that Wall Street is interested, but not at Lennar’s price. Reports are that the investors want 20-30% discounts off of the asking price. That’s pretty steep, and that’s just for 5,000 houses- there’s about to be 1.7 million more where that came from! And of course, let’s not forget about Blackstone (BX) pausing withdrawals on its popular real estate investment fund.

Where Is The Housing Market Headed In 2023?

Forecasts vary for where the housing market is headed in 2023. The party line from the industry at large was that prices would simply level off after hitting crazy highs in early 2022. Now the main line being tossed about is that if you buy now you can refinance at a lower rate in the future. This is summed up by the obnoxious realtor mantra of “marry the house, date the rate”. It’s technically possible but super speculative to try to pull this off because you need a huge decline in mortgage rates for it to work- you could still get stuck with a very restrictive mortgage payment if you overpay for a house and later refinance down to a 5% rate- a lot of comps were set with rates at 3%, which was only possible due to the Federal Reserve running a massive, ill-advised QE program to peg mortgage rates at 3% during a huge housing boom.

Credit rating agencies are pulling out the big guns with their forecasts. Still fairly conservative in its outlook, Moody’s now expects home prices to fall a bit over 10% nationally, with declines in pandemic boomtowns closer to 15-25%.

Moody’s 2023 Housing Market Forecast (Fortune)

These figures imply that the housing bust is just getting started. My research generally agrees. Once housing prices start moving in a direction, either up or down, they tend to continue the momentum for years. International studies on developed economies show that the typical housing downturn lasts about four years on average. Moreover, there’s a lot of momentum in housing. If prices are rising for a given housing market, they tend to continue to rise, and if prices are falling, they tend to continue to fall. If we assume this housing downturn is in line with historical trends, then the peak would have been in January, and we’re about 1 year in. In the last cycle, home prices peaked in 2007 and reached near the bottom by early 2009, although prices didn’t begin to rise until 2012. If this cycle plays out like previous ones, home prices won’t bottom for another year at the earliest.

This might be too optimistic still. If you assume that home prices revert to the mean in terms of wages and that the unemployment rate rises a bit, then prices need to fall about 30% nationally to restore equilibrium. This would mean the speculators get flushed out and prices return to the demographic reality, which is that we keep building houses but our population isn’t really growing anymore. A 30% decline actually would out-do the figures from the 2008 housing crash despite only taking prices back to levels last seen in 2019. To this point, some valuation models on housing suggest that homes are more mispriced today than they were before 2008.

Comparing Today’s Housing Market With The 2000s Housing Bubble

The mainstream narrative of the 2008 housing crash was that greedy banks and mortgage lenders underwrote tons of loans to subprime borrowers, who defaulted en masse and tanked the U.S. financial system. This narrative isn’t wrong per se, but it’s only partially true. While this was eloquently profiled by works like Michael Lewis’s The Big Short, and Charles Ferguson’s “Inside Job,” there were similar housing bubbles over a dozen countries, many of which lacked the subprime lending infrastructure that the US had.

Moreover, there’s been some great revisionist research in the years since the 2008 global financial crisis that challenges the idea that 2008 was mainly a story of subprime. In particular, one paper from professors at Duke, MIT, and Dartmouth stands out to challenge the idea of subprime taking the system down. For me, the most alarming insight of the paper was that it probably wasn’t rogue banks making garbage loans that caused the crisis, but rather millions of middle and upper-middle-class households who overextended themselves by taking out mortgages that were too large for their future earnings. This is important! If the narrative that the crisis was caused by some rogue banks and lying subprime borrowers was correct, then the government could make sure it wouldn’t happen again by cracking down. But if the main problem was the middle class keeping up with the Joneses and overleveraging into asset price booms, then we collectively walked right into the same trap a little over a decade later thinking that “this time is different”.

Other interesting findings from the paper.

- Lax lending standards couldn’t explain the extent of defaults. Subprime loans constantly default even in good times and the interest rates charged tend to more or less reflect the risk. It was actually the supposedly “prime” buyers who overextended themselves and crushed the banks.

- Perhaps like some of your friends at the bar, one study found no-doc homeowners overstated their income by about 20% and were overly optimistic about the future, but by and large, they were not totally lying about their income or income potential. This makes some intuitive sense- nobody wants to buy a home they can’t afford and get kicked out a year later.

- The homeownership rate of low-income buyers actually dropped during the boom as prices rose.

- Out-of-town buyers, flippers, and investors made the worst real estate purchases and were responsible for a disproportionate amount of defaults.

In the conventional sense, lending standards are much better now than they were 15 years ago. But if you believe that housing won’t go down more than it already has because of better lending standards, this is important to read to test your assumptions. To me, the fact that the housing bust in 2008 happened concurrently in so many countries with different lending standards makes a case that this time might not be so different for the housing market after the massive COVID price gains.

For a household making around $100,000 annually and with no other debt, the current lending guidelines say you can buy a house for about $513,000 if you can put 20% down. Around 25% of your pretax income would go to the interest on the mortgage at a 36% DTI. If you’re willing to stretch, then you can buy a house for $616,000 at 43% DTI but you’re paying over $30,000 per year in interest at that point, and total payments of $43,000 per year. With examples like these, you don’t need a Ph.D. to see how housing booms can rapidly turn into busts. I know people who are paying 50% of their pretax income on various kinds of debt services, whether for cars, houses, past vacations, etc. Their credit scores are sky-high, but in many cases, the debt service is supported by a dual-income couple, so if even one partner loses their job, then they’re not going to be able to service their debt. And this is how housing busts happen.

Bottom Line

Home prices continue to rapidly fall. Demand has tanked, and some buyers who overextended themselves by taking out loans to buy houses at bubble prices are quite likely to be forced sellers in the next 12-18 months, especially if unemployment rises. The pandemic housing boom is dead, the bust is spreading, and Powell’s Fed is charting the path of home prices back to fundamental value. For prospective homeowners and/or investors in housing-sensitive stocks, the drama is sure to continue in 2023, and whether some sort of Fed pivot will come to the rescue is top of mind for investors, but ultimately unlikely. At the end of the day, is this time different? I doubt it.

As always, feel free to share your thoughts below in the comments!

Be the first to comment