naphtalina/iStock via Getty Images

Inflation has become the key variable in forecasting growth, earnings, Fed policy, interest rates, exchange rate levels, commodity prices and more. The dollar is still the world’s principal reserve asset and what happen in the dollar sector will affect all other major currency groups and importantly affect commodity prices. Inflation will affect the value of the dollar, itself, both directly and indirectly, further extending the international repercussions.

Expectations (fears) dominate policy

After the Great Recession inflation was not important but the Fed became preoccupied with its evil twin, deflation. After that inflation stayed low and even below the Fed’s target nearly continuously until after Covid stuck in 2020. Still, the Fed managed to conjure inflation obsession after 2015 when oil prices crashed fearing the impact of an oil price rebound on inflation and then fearing the impact of Trump stimulus on inflation. None of those fears came to fruition but policy raised rates from 2015 through 2018 on the fear… expectation… forecast of inflation. Like a child fearing a monster under its bed the cause of your sleepless night may be ‘all in your head.’ The Fed is known to obsess over inflation so with the CPI notching 8% it’s a very good idea to pay attention to what is happening among all the inflation indicators – to what the Fed is forecasting and to market expectations – and to be especially vigilant when inflation is high.

Live by the forecast; die by the forecast

What evolves for inflation and how that plays off the Fed expectations and what markets expect will go a long way to establishing valuations – and changes in valuations – in markets. Fed policy is based on the Fed’s own perception of what inflation is going to do since it is gauging rate hikes based upon its view and assessment of inflation. The markets may have a different view of inflation. And then there’s the question of what inflation really does. When these concepts diverge, the stage is set for fireworks. Ample evidence suggests divergence is in train. Unexpected events will lead to unexpected policies and repricing of assets. It has been said if you live by the forecast, you die by the forecast.

Denial and procrastination as harbingers of fantasy

Let me provide an important recent example and a learning experience for us… Late in 2021 the Fed was engaged in a policy of denial or disbelief about inflation. As the year wore on, the Fed eventually began to admit that inflation was coming but had several reasons why it couldn’t raise rates right away (1) one of them was because it had engaged in extended tapering of securities purchases that was still in progress and represented ongoing stimulus. The Fed was determined not to raise rates and engage contractionary economic policies at the same time it was engaged in stimulative economic policies. The taper kept the Fed on the sidelines. And even though inflation grew very high and even though the unemployment rate was low and fell further, the Fed did not change the taper that it had put in place. (2) For some reason, the Fed handcuffed itself to a policy that kept it from reacting to rising inflation for a full year after inflation accelerated by asserting that the economy was not in a state of full employment. (Economists put the natural rate of unemployment at about 4.5% – the unemployment rate fell to 4.6% in Oct 2021 then to 4.2% in November – if the Fed wanted to take that concept absolutely literally it would not have to wait for March). (3) More to the point (for our purposes here), not only did the Fed not raise rates but in a series of forecasts known as ‘the dots’ the Fed executed several rounds of ‘projections’ that low-balled expected inflation and the economic risks. We have been paying the consequences of those milquetoast forecasts ever since – and that may now continue. Let’s roll the tape on those events:

The Fed’s stepwise ‘forecasts’ from fantasy toward reality

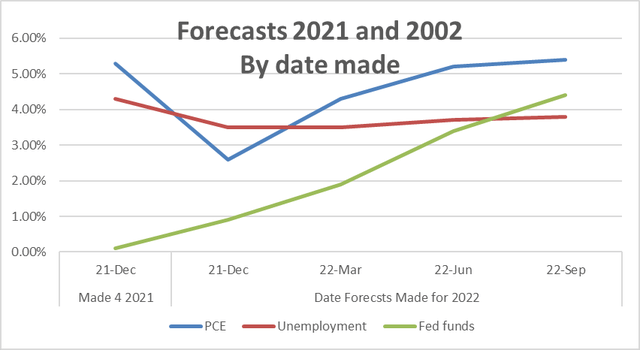

December 2021: The fairy tale – At the Fed’s December 2021 meeting it projected inflation to end 2021 at 5.3% and to end 2022 at 2.6%. At the end of 2021 it projected the Fed funds rate at 0.1% and the Fed funds rate at the end of 2022 at 0.9%. This is based on the median of the Fed’s “summary of economic projections” also known as the SEPs. At that time, the Fed had the unemployment rate projected at 4.3% at the end of 2021, falling further to 3.5% at the end of 2022. Inflation would fall by itself with little rate-hiking, and we would live ‘happily ever after’ as the unemployment rate would fall, too. This was the fairy tale forecast where the Fed sprinkled ‘pixie dust’ and everything was made well again.

March 2022: The tale continues – 2022 things had changed… Actual inflation closed the year 2021 at 6.0%; then for 2022 the Fed expected PCE to end the year at 4.3% (up from its 2.6% forecast of 3-months ago). The Fed was expecting inflation to end 2023 at 2.7% (… here we go again). It was expecting the unemployment rate to be 3.5% at the end of 2022 (still!) and now it was projecting the federal funds rate at 1.9% at the end of 2022 a percentage point higher than three months ago (… enough to decelerate inflation but not to impact unemployment…curious). The Fed even projected the federal funds rate to rise to 2.8% by the end of 2023 at which time the unemployment rate would still be at 3.5% (More ‘pixie dust’ please!). The Fed was planning to raise the federal funds rate more and for that to have no impact on the rate of unemployment.

June 2022: Evil encroaches on ‘The Tale’ – June came and brought a new set of projections… now at the end of 2022 The Fed sees the PCE inflation rate at 5.2% a huge adjustment to what it had been saying previously (4.3%). The Fed also sees the Fed funds rate at 3.4% by the end of 2022 (up from 1.9%) and up to 3.8 (up from 2.8%) percent by the end of 2023. And, finally, the Fed sees the rate of unemployment to 3.7% by the end of 2022 and 3.9% by the end of 2023 (both barely nudging higher).

September 2022: Reality begins to interrupt – This brings us to the most recent set of SEPS at the Fed’s September meeting. The August PCE is up by 6.2% (Core 4.9%). The Fed is looking for the PCE at 5.4% at the end of 2022 (a small upward tweak) still falling to 2.8% by the end of 2023 (The Fed just won’t let this one go…). The unemployment rate is at 3.8% by the end of 2022 but up to 4.4% by the end of 2023 (finally some impact on unemployment, but way in the future). The midpoint for the end of year federal funds rate is now 4.4% in 2022 (a full percentage point higher) and up to 4.6% in 2023 (0.9% higher, than the previous estimate). The Fed has been dragged into partial realism over a series of months as it has discovered that its assumptions were simply unrealistic.

Put together it all looks like this:

Chart I: 2021 and 2022

Fed’s 2021 and 2022 outlook (Haver Analytics FAO Economics )

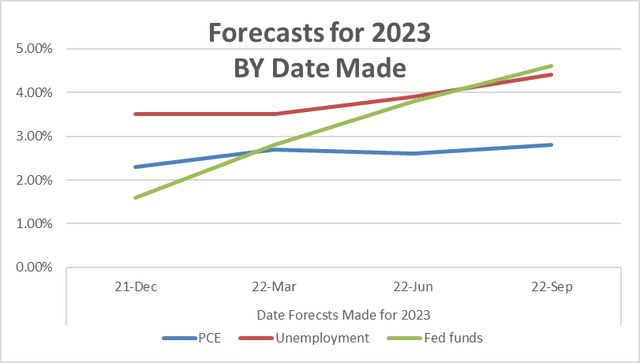

Chart II: 2023

Seps 2023 (Haver Analytics, FAO Economics )

The changes in the Fed’s dots are cited for having had a substantial impact on markets, particularly on stocks; the impact on the bond market has been much less as bonds continue to show extremely moderate long term interest rate levels. I call them ‘extremely moderate’ because they are that in the face of the kind of inflation that’s being run in the economy. Ten-year note yields have been surprisingly sticky in the 3% to 4% range. This is despite this lagging, soft, Fed behavior and a low-ball outlook as the Fed hiked rates by 300bp. It suggests very modest (and firmly held!) private sector inflation expectations… in spite of the Fed.

Forecast errors like moths to a flame…

The above list of Fed forecasts and forecast errors suggests the Fed has repeatedly underestimated inflation – again. I’m not quite sure what the Fed was looking for, or how the central bank with so many economists on board could have waited a full year before raising the federal funds rate and let the CPI climb to over 8% unobstructed by even a pip of a rate hike. But it did.

Generally speaking, monetary policy needs to ‘do something’ other than to just assume that the inflation rate is going to fall. A lot has been made of how the Fed did not act in 2021 thinking supply chain problems would heal themselves. Then it decided it had to act… But this analysis shows that the Fed still expects inflation to fall all by itself; it has not given up on the view that supply chain problems will heal themselves and lower inflation all by themselves! The evidence for this is that the Fed has inflation falling before it gets Fed funds above the PCE pace. Real interest rates turn positive because inflation falls and that puts inflation below the Fed funds level (and yes, the Fed funds level is lifted, but PCE is going to fall from 6.2% (currently) to 2.8% by year end 2023 to turn real interest rates positive. Most of the work will be done by falling inflation, despite the fact that real interest rates contribute no braking assistance at all.

THIS IS FED POLICY. If you are bullish on stocks or bonds, then you must believe this is TRUE – that a large slug of inflation will fall all on its own. If it is not true, there is a rude awakening ahead. Are you attuned to this?

The Forward Guidance… Or Misguidance?

Jim Bullard is the most vocal Fed official defending forward guidance as a road map to Fed credibility and faster control of inflation – and he argues – with less Fed action. But I don’t see it that way at all. From 2015-2018 the Fed hiked rates without looking at data employing a ‘bygones’ policy that ignored reality. In that case the forecasts it based its action on were persistently wrong and the errors were persistently ignored. What good is that guidance? Now, no one knows the future, but the Fed has been hopping up its inflation and Fed funds estimates regularly… at first not raising its Fed funds estimates at all, projecting inflation far too low time and time again. The problem with forward guidance may be that when such a huge rise in rates seems to lie ahead the Fed just can’t tell us. It would prefer to forecast ‘the most optimistic scenario’ and then modify its views higher time-after-time… after time. Furthermore, the Fed’s forward guidance might impede it acting of changing its view as it did with the taper – if we take the Fed at its word. When it laid out a taper it was loathe to modify it because the market had been given guidance. When the Fed is way behind the curve it may simply not be possible for the Fed to issue ‘correct guidance.’ Correct guidance might spook and crash markets. The Fed simply cannot admit the gravity of its mistake; it must be revealed a bit at a time like peeling the skins off an onion.

The Great Disappointment… or Great Hoax?

We can learn about how policy works by looking at what the Fed has done and what impact this had on market events around us – even more than by what the Fed says… Right now, the biggest thing that we’ve learned is what a great disappointment monetary policy has been. There is no end of talking about how rapidly the Fed has raised rates and this has created a certain schism among economists. Some think the Fed has moved too fast and it risks financial instability. Others think the Fed needs to get the funds rate up higher, quicker… and some think it needs to go above the rate of inflation sooner.

The reason that the rate hikes themselves are not a deterrent to activity because it’s the level of interest rates relative to inflation determines the deterrence of inflation, and that level has not reached that point yet! Despite all the rate hikes, inflation continues to reside above the Fed funds rate. Borrowing money is profitable if you can earn the inflation rate. There is absolutely no reason to think that the economy should have slowed or that inflation should have slowed during this period of rate hikes! So has this been a true expectation, or an expectations hoax?

Multigenerational Credibility?

The Fed has potentially a very serious problem on its hands; it doesn’t want to talk about it because it wants to assume that it doesn’t have this problem. The Fed wants us to believe in multigenerational credibility. Under Paul Volcker the Fed was willing to engage in draconian acts to drive the inflation rate down. However, after Volcker we had Alan Greenspan, Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen and now we have Jerome Powell. Paul is no longer alive. My question is how much of that toughness from Paul Volcker has been transmitted down the line? Has Volcker’s credibility enhancement for the Fed outlived him? Is the Fed’s credibility institutional or does it come from its ever-changing chair and the FOMC?

‘Simon says’ 2%

In 2012 when Bernanke shifted over to inflation targeting this was a procedure wholly based on Fed credibility and expectations. When the Fed gave us its 2% inflation target it did not promise us that it would do anything specific to achieve it. It promised nothing in terms of economic growth, in terms of real interest rates, in terms of money supply growth -nothing at all. The Fed cut out all these intermediate steps and simply promised us 2% inflation. With inflation targeting, Fed policy becomes a ‘black box.’ Who-knows-what-goes-in but 2% inflation comes out… Under Paul Volcker there had been a pledge to control monetary aggregates. Controlling money supply was the mechanism by which inflation would be controlled. We could look at the Fed’s progress in controlling money supply and we could derive some confidence about the Fed’s ability to achieve its targets from that. Bernanke did away with all of that. It became a game of ‘Simon says.’ And that’s good enough if ‘Simon’ has “CCC”: competence, conviction, and credibility.’

Outcome is the essence of Fed policy

In this world your confidence helps to create what you are confident of. However, if you are not confident and if your central bank does not have credibility, your lack of confidence tends to create the problem that you fear most. This is why Fed credibility, which can be expressed as inflation expectations, is so important. If the Fed loses that, it loses everything because this is more than just a linchpin for policy, it is the essence of its policy. Remember policy is a ’black box’ – only the ‘output’ matters.

The CPI-PCE dilemma

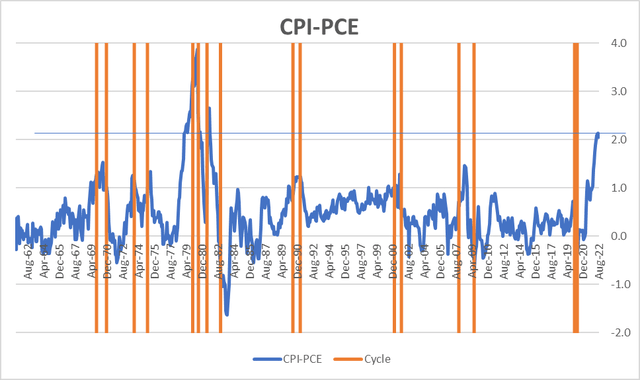

There is the added problem right now that while the Fed targets the headline of the PCE index, it will from time to time place some emphasis on the core PCE index if inflation gets too volatile. However, the public is more comfortable looking at something called the CPI, the consumer price index. It didn’t use to make too much difference which one of these indices you looked at because the CPI tended to run hotter than the PCE index but only by about 0.3 percentage points or 0.4 percentage points per year. However, right now the gap between the CPI and the PCE is closer to two full percentage points. That is a massive difference

Chart III

PCE Vs CPI gap in 12-Mo change (Haver Analytics, FAO Economics)

If you look at this chart carefully there may be a reason not to worry so much about the gap. The last time that we had such a huge gap between these two price indices was back in those days when Paul Volcker was raising interest rates very sharply and inflation was extremely high. Also, you’ll note a tendency for the gap between the PCE and the CPI to become enlarged during recession periods and then to fall back rather quickly in the recovery. With this chart in mind, I am going to set the CPI aside because it seems to me that while the CPI inflation rate is massive and it does scare the heck out of people, it looks like a cyclical distortion of long standing, which occurs during times of very high inflation and possibly during recessions. History shows after inflation is tamed the normal relationship between the PCE and the CPI is restored. That suggests we don’t lose anything by talking about inflation in terms of the PCE and setting aside some of these very disturbing numbers associated with the CPI. Okay – but we are not done with the CPI yet…

Expectations matter – but what are they?

Our final question is about what markets think. Here we have different ways to extract market forecasts. I prefer to look at the University of Michigan survey which is a survey of expectations about the CPI. University of Michigan offers two-time frameworks by looking one-year ahead and at the longer horizon, what is expected for five or five to 10 years ahead. The number that emerges from that longer process is better-related to what people think might happen and is disconnected from the specific events of today. That is desirable for assessing expectations. You want to know, after this mess is cleaned up, what inflation is going to look like in the future.

The University of Michigan five-year ahead expectation on the CPI for October has a mean expectation of 3.3% and a median expectation of 2.9%. Given that the Fed seeks a 2% inflation target these are numbers that are high (of course) but well within the bounds of saying that inflation expectations are still relatively well behaved… or are they?

The differences between The PCE and the CPI is huge. If people are literally forming their expectations in the U of Michigan survey based upon the CPI the interpretation of the U of M index flips! In that case, these are extremely low inflation expectations for the PCE given that the CPI is currently running at 8.2%. If we subtract the difference (use 2%) between the CPI and the PCE from the mean and median to ‘convert them to PCE terms, we wind up with a mean expectation of 1.3% for the PCE and a median expectation of about 0.9% – these are both extremely low numbers, no longer high numbers! If those adjustments are warranted (and there is no way of knowing) then inflation expectations are extremely low – and that has been the message from the bond market for some time.

Reality… flips!

If inflation expectations on the PCE are really this weak then does the Fed really have to raise interest rates as quickly or as high as it thinks it does right now? In view of our earlier discussion, you might find this an extremely strange question. Well, I certainly find it so. But the U of M survey does not stand alone and is consistent with enduring low yields on long term US treasury securities.

So… is recession coming?

Inflation, the Fed funds level, and bond market are three variables that seem out of sync with each other in a serious way. I have been thinking since the end of 2021 that the economy is headed for recession. I haven’t had any particular start date in mind except that it probably wouldn’t take more than a year. My concern was and is that inflation was so high the federal funds rate was so low and yet that the market determined yield on the 10-year treasury note was so low that we have no idea what expectations are or what policy should do. In this framework you can recognize the yield on the 10-year note as being related in some way to inflation expectations. The yield on the 10-year note, at the 3% to 4% range, while the CPI inflation rate is running at 8% is quite remarkable and it seemed to me at the time (and now) that we were looking at divergences in markets that were irreconcilable. That meant they would almost certainly lead to a policy mistake, and to recession, or would lead to the necessity of a more draconian policy direction that itself would lead to recession.

What you BELIEVE matters (what’s TRUE matter more) – If you are an investor, these are all the things you need to think about when it comes to inflation. What do you believe? Inflation is something that seems so simple to people. But, in fact, it’s extremely complicated (as you may have surmised by now). Economists really don’t understand it and can’t forecast it very well. And no matter how many models economists have, how many equations, and how many variables, none of that really seems to help that much.

Paint it black…

What I have laid out here is a schematic of the economy in black hole with monetary policy made by a black box. It’s in a much riskier situation than most people now think it is. I also don’t think it’s going to be that easy to get back to or to stay at 2% inflation, post Covid so the Federal Reserve is going to have to be more active in the future and more vigilant about shocks in the economy than it has been since it went to interest rate targeting (in 2012). If The Fed still benefits from the legacy of Paul Volcker, then it’s only symmetric to think that the Fed is going to be dogged by the legacy of Jerome Powell as well, and by the inflation overshoot.

A difficult future

Quite apart from monetary policy and world events we have some very difficult political circumstances in play that are not going to make it easy to deal with our fiscal challenges and the demographic changes that are going to sweep across the economy. We are only seeing hints of some of the issues such as the poor performance of productivity and the notion that the worm has turned to such an extent that workers can tell firms what they’re going to do and how they are going to work. This clearly is not the way to price stability. I’m convinced that inflation is going to set the tone and future Fed policy will be more activist. Growth is going to be disappointing. The future is not dystopian, but it is not the utopian fairy tale view that the Fed keeps trying to forecast either. ‘Happily ever after’ may not be in the cards. My worst fear is that the Fed is trying to draw to an inside strait needing a card that simply is not in the deck.

Be the first to comment