matejmo/iStock via Getty Images

Regulators’ myopia

The underlying problem that has splintered the market for short-term wholesale debt is the failure of government regulators’ vision.

First, the regulators’ reaction to the 2007 financial crisis was to increase bank safety by reducing the commercial banks’ capacity to perform their role as financial intermediaries, requiring market-makers to hold extra capital, and discouraging banks from accessing the wholesale deposit market.

Regulators failed to see protecting the entire process of financial intermediation as their responsibility, instead seeing protecting a component of the process, the commercial banks, as their job.

Second, the regulators’ answer to LIBOR’s replacement was to protect the index, not the market. Again, the regulators failed to see their responsibility to the underlying market for commercial debt. Their job, they believe, is to provide an index that is impervious, thus unfortunately also unresponsive, to market chaos.

Regulators have abrogated their responsibility for market function, focusing instead on protecting links of the chain of market stability at the expense of the strength of the chain itself.

The for-profit links in the chain of financial intermediation must strengthen themselves or await the next collapse.

SOFR’s inadequacy

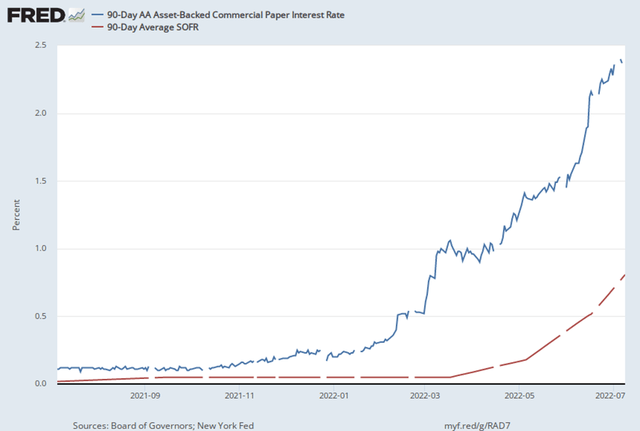

The volatility of short-term rates blasts off, returning to normal pre-financial crisis levels. As a result, the spread between the monetary policy-related secured overnight financing rate (SOFR) and the cost of corporate debt (measured by the 90-day commercial paper rate) explodes, overwhelming the unimportant SOFR portion of the cost of credit. This behavior thus lays bare the inadequacy of SOFR as a short-term credit risky interest rate index. (See the graph above.)

Debt markets lost their focus

How can financial markets develop a credible replacement for Fed-controlled SOFR? There are four important requirements for an index.

- It must be a weighted average of transaction rates.

- It must be available even when credit markets are threatened with failures.

- It must reflect current credit conditions in the market for corporate debt.

- It must be forward-looking, reflecting expected conditions during the coming three-month term.

SOFR fails two of the tests

- SOFR reflects credit conditions in the Treasury-based credit-riskless repo markets. It is unresponsive to credit risk.

- Three-month SOFR is a backward-looking rate, describing the history of the market, not its expected future.

Creating a reliable corporate short-term debt index requires:

- A short-term debt instrument that will remain in demand during crises that threaten primary money market funds.

- A homogenous instrument that survives individual corporate failures within the broader corporate credit system.

- A market with liquidity comparable to the soon-to-be-retired Eurodollar futures market.

Ad hoc indexes also fail

The first attempted SOFR replacements – interest rate indexes like the Bloomberg short-term bank yield index (BSBY) – were the first post-LIBOR commercial versions of a short-term credit rate index. But these indexes are doomed to failure too because there is a substantial likelihood that the existing short-term credit market will shut down during an economic crisis, leaving the world temporarily without a way to value short-term debt. No index constructed from interest rates in the existing commercial paper market will work.

A viable index can thus only be created from a newly created market with crisis-resistant demand and supply.

Wholesale deposits were once a more useful measure of the current cost of corporate debt than commercial paper. Banks focused on the investor demand for deposits – deposits are a demand-side focused instrument – whereas commercial paper has always been issued to match the irregular corporate need for short-term funding – a supply-side focus.

A successful market summary instrument must balance the needs of the demand and the supply side of the market for short-term credit.

Deposit yields are no longer feasible indexes. As banks have gradually withdrawn from the wholesale deposit market in response to the regulator’s higher capital requirements, bank deposit yield-based interest rates have ceased to be viable indexes for the measurement of the current cost of corporate short-term debt. Bank deposit amounts are too sensitive to the health of the economy to provide sufficient liquidity to enable the calculation of a transaction-based index.

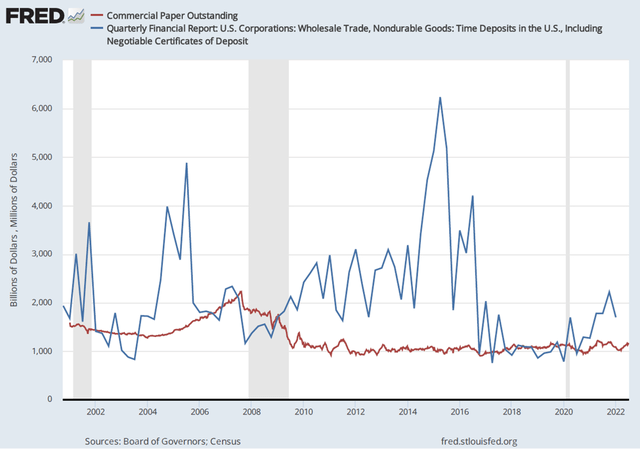

But as the graph above shows, the outstanding supply of wholesale bank deposits has become too volatile to be a dependable source of an index. The supply of commercial paper is far more stable. Yet the commercial paper market has issues of its own that providers of a credit index would need to overcome.

Liquidity

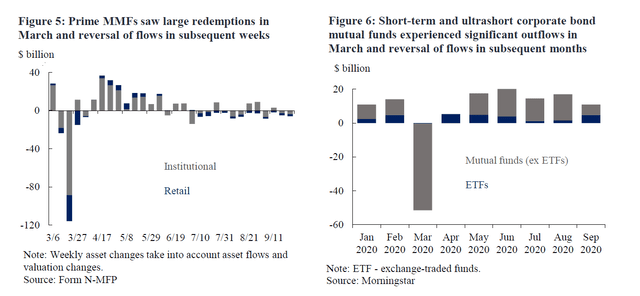

The primary reason today’s commercial paper market cannot be the basis of an interest rate index is its illiquidity. There is a tendency for demand for individual issues to collapse during crises, as the graphic below shows. Furthermore, after a specific issue is sold, it rarely trades in a secondary market.

As the SEC staff report notes, the collapse is a result of investors’ (demand-side) rejection of the instrument rather than disinterest from borrowers.

In summary, two key issues must be addressed to provide a stable short-term credit market index.

- The index must be the product of transactions in a liquid market.

- The underlying market must continue to function in crisis conditions.

How to build a reliable debt index

The commercial paper market’s liquidity problems can be divided into a supply-side problem and a demand-side problem.

Supply-side. The wholesale bank deposit market can no longer provide an index like LIBOR due to the regulation-induced supply problem.

In risky situations, post-financial crisis regulatory capital charges force the banks to pull in their horns, reducing deposit supply. The regulators have denied the banks the opportunity to provide markets with a crisis-stabilized investment alternative with their pressure to curtail wholesale deposit issuance.

Demand-side. In the commercial paper market, money managers pull their funds from the primary Money Market funds (Prime MMFs) during crises, creating a demand problem. To resolve that problem the tools of finance – notably the issuance of investment vehicles designed from very risky assets to create less risky assets through diversification is useful.

A new version of the idea of an investment fund. Prime MMFs cannot supply a credit market index because they are subject to collapse during financial crises. But this weakness of prime funds could be resolved by creating a money market instrument backed by a fund created with a different objective.

Prime funds attract investors by promising higher yields as well as less risk. To achieve this goal, prime fund managers limit the selected commercial paper to issues that promise an above-average yield.

By expanding the selection of issues to represent the entire market, the share of any single issue in the whole could be reduced to insignificance, giving the fund assured stability.

How to build a liquid market.

The creation of the stable fund above begs an important question. If the fund does not seek to improve the expected return, who would invest? The answer lies in an understanding of the workings of the Eurodollar futures market.

The Eurodollar futures market is liquid because it summarizes the average performance of the credit markets. For this reason, its function can only be performed if a decline in its value is as likely as an increase.

This explains the conundrum that regulators cannot explain – the robust liquidity of Eurodollar futures despite the extreme illiquidity of its spot market kin, the London Interbank deposit market.

To settle a liquid futures contract, a financial instrument needs only to be valued at the close on settlement day. The liquidity of the delivered security is irrelevant. And settlement value that day is easily discovered in the futures market.

Conclusion

The recent run-up in short-term rates exposed the inadequacy of SOFR as a measure of short-term credit risk.

There is a private-sector solution to the failure of SOFR to provide a useful hedge of short-term credit risk. The solution links a futures market to a spot instrument created by the exchange that trades the futures contract. The resultant index would do more than replace LIBOR. It would be a substantial improvement.

But the private sector – investment management firms, exchanges, and broker-dealers – must accept the challenge. This for-profit answer is beyond the remit of financial market regulators.

Be the first to comment