imaginima

Warren Buffett famously said (paraphrased) when you put great management in charge of business with terrible fundamentals, odds are the fundamentals will win out. That’s not to say management quality is unimportant, rather the fundamental dynamics of an industry are critical and may be the determining factor. There have been a lot of great articles analyzing the great quality of Occidental Petroleum’s management or oil reserves, but little attention has been paid to why the oil industry dynamics have become attractive to the Oracle. This article attempts to capture that underappreciated catalyst: changing fundamentals in the oil industry.

Last week, OPEC shockingly hinted that it may be considering a production cut. With Brent crude oil prices at $90-$100, OPEC cutting production at these price levels would be quite a big shift from past practices, especially if you consider that OPEC was engaged in a price war that pushed oil prices to negatives just a few years ago and then brokered a production cut to boost oil prices to more “normal” levels. OPEC’s rush to verbally intervene when oil prices just soften slightly almost reminds one of how the Fed used to verbally reassure stock markets whenever there was a correction (that is before the monetary tightening in 2022).

What may be the root cause of this and are there deeper implications? This article attempts to delve into an underappreciated catalyst for the oil industry – namely the reluctance of major oil producers to increase supply due to uncertainty of future demand, as well as implications for oil stocks like Occidental.

Peak oil demand leads to panicked oil producers

“Peak oil” hypothesis gained wide circulation in the 1970s during the commodity inflation and general doom and gloom. However, this hypothesis was more from a supply perspective (which turned out to be less imminent than initially feared). What we’re looking at now is peak oil demand.

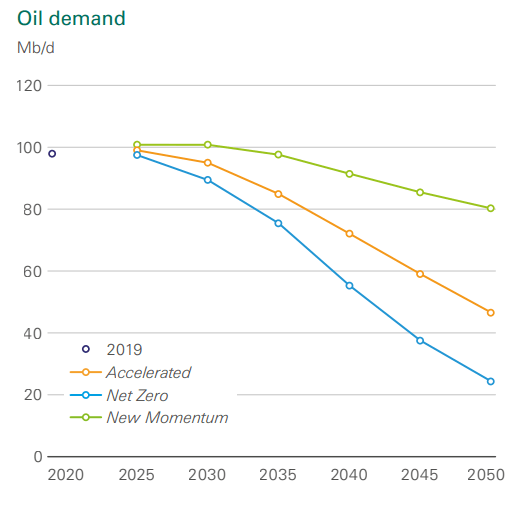

BP Energy Outlook 2022 forecasts peak oil demand that gets progressively worse in the future. In fact, there is no scenario under which oil demand is not flat or lower at 2025 (compared to 2019) and does not precipitously decline by 2050, which it attributes mainly to “the falling use of oil within road transport as the vehicle fleet becomes more efficient and is increasingly electrified.”

oil demand forecast (BP)

This makes sense given the accelerating speed at which electric vehicles (“EVs”) and renewables are taking over the market – in June 2022, EVs accounted for 25.9% of auto sales in China alone (with roughly 80% being purely EVs and only 20% hybrids).

This is deeply worrying for oil producers for several reasons:

- Oil exploration has become increasingly expensive, something the peak oil theorists have bemoaned since the 1970s. For example, the Kashagan oilfield discovered in 2000:

- requires an estimated $150 billion of investment to fully develop. 20 years after its discovery, it only produces 300,000-400,000 bpd even after c.$60 billion of investment.

- The capital to develop the Kashagan oilfield mainly came from western oil companies – even if we ignore the fact that given the current geopolitical climate, oil majors will think twice before undergoing such projects.

- The exorbitantly high capex required to bring oil to market will have a twofold impact: (I) companies will be less willing to make such large investments given the uncertainty – investing tens or even hundreds of billions of dollars (even in a consortium) to see oil prices at breakeven or loss-making prices years later? No thank you! We will just buyback our stock. (II) the price of oil has to be much higher to incentivize increased production.

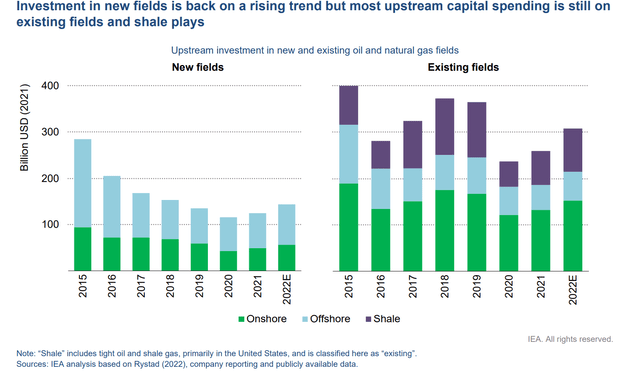

- As shown in the chart below from IEA, investment in new oil and natural gas fields Is still way below 2015 levels and is not expected to increase much in 2022E despite much higher oil prices.

Oil capex (IEA)

- Excess capacity can endure for long periods:

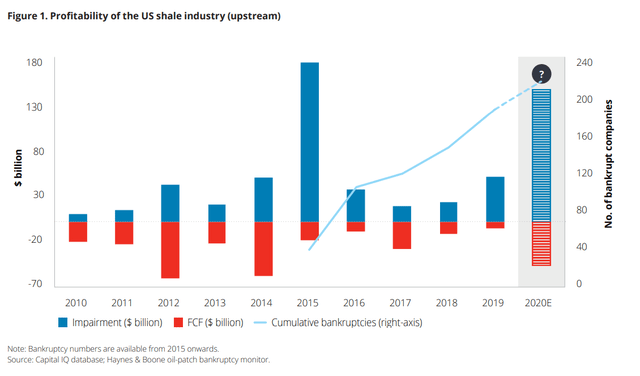

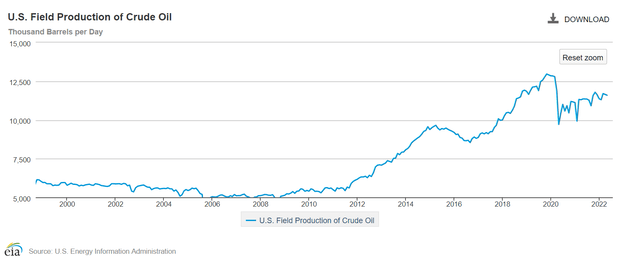

- Oil, like most other commodities, has a long lead time to bring production online. Once production is online, the capex is a sunk cost and producers continue pumping even if unprofitable. As shown below, the shale boom that started c.2013, caused US oil production to increase from 6 million bpd to 10 million bpd by 2015. Despite oil prices crashing in 2014 and remaining low for the next few years, U.S. oil production continued to increase till 2020. US shale oil production endured for over 5 years despite spend most of the time bouncing between loss-making and not very profitable.

-

- In mid-2020, a study showed that from 2010-2020 the U.S. upstream shale oil industry generated net negative free cash flows of $300 billion, impaired more than $450 billion of invested capital (Implications of COVID-19 for the U.S. Shale Industry). Once the craze began, mountain piles of money were thrown into shale which didn’t make money. In fact, if these investments were made in a more measured pace, it might have been more profitable for everyone involved.

Shale oil negative cashflow and investment returns (Deloitte)

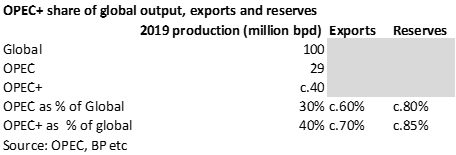

- OPEC+ has the ability to influence the market given its chokehold on tradeable oil: Compared to many other commodities where the producers are disperse enough not to be able to influence the market in a significant way, OPEC+ has a significant ability to influence supply – while OPEC+ might only produce c.40% of the world’s oil, it exports 60-70% of the world’s tradeable oil which is arguably more important for pricing power. Also, it controls 80-85% of the world’s reserves, most of these being relatively low production cost reserves.

opec share of global (OPEC BP)

- Oil is known to have a high elasticity in that small amount of supply/demand balance changes can have a much larger impact on price, hence the tail can wag the dog – even a small oversupply could cause the price to be materially lower. So even if oil producers in aggregate gets the oil forecast demand wrong and the market is oversupplied by just a million or a few million barrels per day, it could be catastrophic for oil prices and profits (from oil producers’ perspective anyway). For a oligopoly like OPEC+, it is obvious that losing a million or two barrels a year through production cuts (which corresponds to maybe 3-6% of total OPEC+ volume) is more than compensated by the significantly higher sales price per barrel.

In a nutshell, oil demand is slated to peak while on the supply side new oilfields are expensive to develop, excess production could persist for a long time once it comes online, a little oversupply could mean a big price reduction and OPEC+ can do something about it. Motive and capability equals OPEC+ keeping oil prices high for the foreseeable future through curtailing production. Better yet, these days curtailing new exploration and production can be done in the name of “green,” so producers can take cover with climate change as a raison d’etre (note: this article does not attempt to wade into the debate over climate change, it just points out that producers can curtail production under the name of addressing climate change whereas these practices might otherwise have been challenged on anti-monopoly grounds).

The age of the supply cartels

Speaking more broadly, being incentivized to curtail production is not just something that’s happening in the oil sector.

Ever since the industrial revolution, mankind has mostly been producing more and consuming more. Except for rare cases where supply was so concentrated so that there was a “natural” monopoly (e.g., platinum or diamonds or land in great locations – “buy land, they’re not making any more of it”), in other cases it would usually not make sense to attempt to control the supply. With factories and railroads and steamships, pretty soon production was no longer an issue. For many if not most products, the key to profitability was not controlling supply, but access to market (such as Buffett’s repeated admonitions about “share of mind”) and making new/attractive/great products (i.e., there are so many phonemakers but only one iPhone maker).

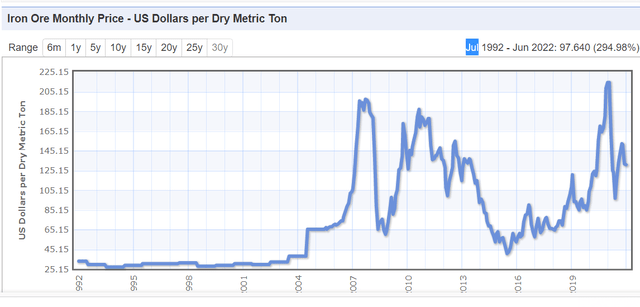

The great commodity inflation of the 1970s ended up with a bust because commodities were still plentiful enough and eventually enough supply would come online with and destroy any long term attempts to corner the market. In fact, from the point of view of the 1980s, before the Chinese economy began to show an insatiable appetite for commodities and consume over half of the world’s supply of many commodities (copper, etc.) annually, the medium term fundamentals (which I would define at 5-10 years) for many commodities was quite bleak – the production potential of many commodities far outstripped any reasonable demand increase from developed countries. To use iron ire as an example:

- in 2021, the world produced 2.6 billion tons of iron ore of which 32 million tons were used by the U.S. Yep, you saw that right, due to the US already passing its industrialization stage, most steel in the US is recycled, so very little new iron ore is needed. The current annual global production of iron ore is enough for the US to use for a century. That’s why before China entered the WTO and started becoming the world’s factory, iron ore prices were somewhere like $20-$30 per ton for decades, essentially not much more valuable than gravel.

- But here’s the kicker, while iron ore producers were happy to produce at $20-$30/ton for decades, this was because they could expect a reasonable return on capital from those prices and demand was forecast to be stable and there wasn’t much there could do about it (with so much potential supply, if anyone tried to gouge prices, someone else would dig up the supply and take their place). So these iron ore mines would just be treated as slightly profitable income generating properties selling at gravel prices.

- What if demand was forecast to decline consistently, perhaps even terminally?

- China actually underwent a period of this in 2015 and 2016 where it appeared peaked industrial demand had been reached (due to a peak in real estate construction volumes and large construction in progress and housing inventories). Many commodities were sold at lossmaking prices and supply was curtailed to restore balance, a comparison of some major products shown below

Prices of certain commodities in China pre and post supply curtails

|

Values in USD/ton |

2015-16 prices |

2022 latest prices |

|

Thermal coal |

$30-$45 |

$110 |

|

Coking coal |

<$100 |

$300 |

|

Glass |

$110 |

$200 |

|

Aluminum |

c.$1300 |

$2400 |

Source: public information

-

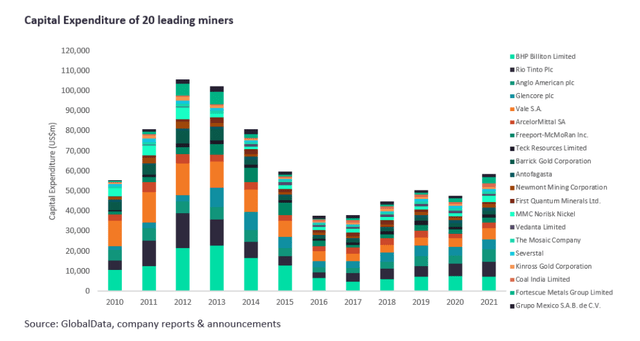

- Iron ore majors (as well as metal miners in general) reduced capex starting in 2012/2013 due to a pessimistic forecast of future Chinese demand. During the demand rebound in COVID-19 pandemic, iron ore prices surged to over $200/ton (compared to less than a third of that pre-COVID), which may be a foreshadowing of what’s to come in the oil market.

Metal miners capex (GlobalData)

The oil market could be undergoing something similar, albeit on a much larger and global scale of “producer see producer do.”

What this means for Occidental

If we assume that oil prices will remain at a high price for the foreseeable future (it might be $80 or $120 or higher, depending on the actual situation and catalysts, I’m not trying to judge what the exact price would be except that it is likely to remain at relatively high levels, e.g. prices similar those average of H1-FY22) then how would this impact Occidental?

Illustrative Comparison of EVs and FCF for selected major oil companies

|

USD billions |

H1-FY22 Operating cashflow |

FY22 forecast capex |

FY22F free cashflow |

Market cap |

Borrowings |

EV |

EV/FY22F FCF |

|

A |

B |

C=2*A-B |

D |

E |

F=D+E |

G=F/C |

|

|

Exxon Mobil (XOM) |

34.7 |

21-24 |

45 |

408 |

39.5 |

447.5 |

10 |

|

Chevron (CVX) |

21.8 |

15.3 |

28.3 |

320 |

26 |

346 |

12 |

|

Shell (SHEL) |

33.4 |

23 |

43.8 |

207 |

83 |

290 |

6.6 |

|

Occidental (NYSE:OXY) |

10.4 |

4 |

16 |

68 |

22 |

90 |

5 |

Source: public filings

Current EV/FCF do not appear to be fully reflecting the assumption that these high oil prices could be here to stay. Especially for Occidental, which has an EV to FCF of only 5, significantly lower than other major oil companies, which means if oil prices remain at current levels for just 5 years, Occidental shareholders and creditors get all their money back. Given that European natural gas prices are high all the way to winter 2025 and it takes years for a production upswing to take place, it seems a safe bet to recoup the investment in 5 years.

Buffett’s investment in Apple, railroads and Occidental

When Buffett invested in c.$36 billion in Apple starting in 2016, some market observers felt Apple was already quite fairly valued with a market cap of $600-700bn. Turns out Apple has quadrupled off these levels. Similarly, Buffett acquired the railroad company Burlington in 2009 for $34 billion. What do these two investments have in common?

First, they were big, mature companies with overwhelming market share in an industry that had reached a certain level of maturity.

Second, they required little capex (as percent of operating cash flow) to maintain the dominance

Third, the market was underpricing these companies’ ability to capitalize off the above. Other comparable railroad companies such as Union Pacific have gone up 10X since 2009.

The combination of market dominance, pricing power, limited capex and reluctance to increase supply forms into powerful underpinnings for sustained, high levels of profitability and cash flow. Add in expectations of declining demand and it becomes a gold mine. This combination is not unprecedented:

- The book “Competition Demystified” describes how lead was turned into gold as lead additives were phased out over a course of 20 years due to statutory requirements. During this period, lead additive producers saw high profit margins, with companies such as Ethyl earning nearly 50% operating margins on their lead additive business towards the end. This was hugely profitable because there was no incentive to increase supply for something that would be phased out by law. The same expectation may be playing out in the oil markets and among oil producers.

- This is also similar to what happened to tobacco companies in a market where sales volumes shrank for decades but average sales prices kept increasing and the great performance of tobacco stocks has been a well-documented case.

When it comes to oil, there’s also the additional bonus that OPEC+ is actively managing to keep prices high even at their own expense and it will take years before the world figures out whether alternative energy sources will lead to peak oil demand or not and even if the peak oil demand hypothesis is eventually discredited it will take many years for increased capex to bring adequate amounts of new oil online.

Other potential catalysts to watch:

Without getting too much into politics, I will list below some potential catalysts to watch:

- European switching of fuel: Natural gas prices have continued to reach new highs and there have been reports of Europe switching to oil-related products to fuel power plants and factories, however the reported amounts have been small so far.

- Russia: Again without getting into the politics, purely from a cost-benefit perspective, Russia might cut the flow of oil supplies:

- Europe is vastly cutting back on natural gas and it appears Europe might have enough to plod through winter

- The current prohibitively high natural gas prices will cause Europe to seek new sources. These new sources won’t come online this year or even next year, but at these rates and this urgency, it will make sense to expedite. For example,, Europe could vastly expand LNG terminals, this might take several years but this is doable. The most ardent green renewable supporter is not going to be against building LNG terminals if he has to chop wood to keep his house warm in winter.

- This means Russia’s strategy of withholding natural gas supplies only has a validity of 2-3 years before the Europeans build the infrastructure to obtain new supplies. This increases the likelihood that Russia has to go for a quick one-two punch and decrease oil flows as well as natural gas flows.

- There has already been several cases where Russia has implied the potential to reduce oil flows, for example Russian courts ruled a potential suspension to the Caspian Pipeline Consortium’s operations (subsequently reversed on July 11, 2022) which would have essentially halted Kazakhstan’s oil exports.

- The odds of this event could also increase if western nations attempt to cap prices paid for Russian oil at materially lower levels.

- Saudis: As discussed above, the OPEC+ cartel, which the Saudis are heavily influencing, focuses on maintaining prices even if at the expense of production volumes. Despite the Saudis mention to potential production increases after Biden’s fist-bump, this hasn’t really panned out into tangible oil production increase. Given the above dynamics, it looks like the Saudis will symbolically do something when high oil prices is a concern from the US but stick to its strategy of keeping oil prices high when it’s not, which may evolve into the “OPEC+/Saudi put” similar to the “Fed put” in the equities market.

- Iran nuclear deal: If this comes through, Iranian oil could come online. It may take a certain amount of time before oil flows return to normal, but in the long scheme of things this would be an addition of a million or two barrels. I would not expect this to have a permanent impact given the above dynamics – supply cuts in other areas may limit/negate the overall impact, but any short term dips in the price of oil due to expectations of increased Iranian exports may be a great time to buy.

- The Fed: The Fed is clearly signaling to the market not to expect any rate cuts and to expect rates to remain at elevated levels as per Powell’s message at this year’s Jackson Hole. With a stronger dollar and increasing recession expectations, oil prices may fall at some point, which may actually be a good buypoint for oil stocks.

Summary: Peak oil demand has fundamentally changed the oil industry from growth-driven to “harvest mode” which is likely to drive oil producers to invest less in capex that will curtail supply and keep prices high even without geopolitical considerations. The price of oil stocks, especially Occidental Petroleum is not fully reflecting these developments. Any dip in oil prices (and oil stocks) due to the Fed tightening may be a good point to buy and/or add further due to the “OPEC+/Saudi put” stabilizing prices.

Editor’s Note: This article discusses one or more securities that do not trade on a major U.S. exchange. Please be aware of the risks associated with these stocks.

Be the first to comment