Mario Tama

Netflix (NASDAQ:NFLX) is getting way worse of a rap than they deserve given the way they control costs, their business history and their positioning relative to peers in the entertainment industry. Their lean production model is rare in a world dominated by big studios, but it’s produced some absolutely stellar results and underscores their commitment to keeping expenses under control, a virtue heavily underappreciated these days. They’ve weathered economic downturn and competitive upheaval before, surviving the 2008 recession and coming out of it an absolute juggernaut while embracing streaming media alongside their groundbreaking DVDs-by-mail service until it became clear optical media was no longer en vogue.

The jaw-dropping crash from the high of November 2021 is as much a return to fair valuation as anything. The market got so far out ahead of itself, with FAANG at the forefront, that any large-scale pullback such as that currently in progress would be the skimming of the froth and an opportunity for analysts to drop price targets without needing to admit they had gotten caught up in the exuberance. While Netflix is certainly not a “value name”, it’s handling the current market turbulence fairly well after a few quarters of pain, and their financials look solid enough to endure a downturn and come back roaring once again.

Costs And Content

If there’s one constant in business and life, it’s that a dollar in savings is worth more than a dollar in revenue. When it comes to budgeting for content, Netflix goes full shoestring budgets almost every time, but they and a good portion of their competition know when to double down on their tentpoles. The Crown and Stranger Things season 3 have production budgets of about $10 million an episode, but Stranger Things 4 reportedly cost almost $30 million an episode. Paramount (PARA) has thrown a decent amount of money at Taylor Sheridan’s works, with his Yellowstone prequel series 1883 doubling the $6-8 million price per episode quoted for his typical shows. HBO (WBD) let their production costs for Game of Thrones grow all the way up to $15 million an episode in the final season, before striving to keep costs for House of the Dragon under $20 million an episode, a savings they credit to increased efficiency after working on previous shows.

Compare these far-and-wide content seedings to Disney (DIS), who will drop $25 million an episode on Marvel shows like WandaVision, or The Mandalorian at $15 million an episode; or Amazon, who is shattering records for their costs on The Rings of Power, with the first season costing nearly $60 million an episode and a rumored nearly $1 billion in total being committed to the show so far. Blockbuster budgets may have made sense in the era of linear TV and movie theater releases, but the streaming era has proven that lean-and-mean is a viable option too.

Running lean on production costs also has a side benefit of allowing for a much broader slate of content compared to a “Friday night lineup” style programming schedule that linear TV follows. Friends of ours mentioned a favorite Netflix show for their kids was DinoTrux, a show with such a bizarre premise – dinosaur-themed heavy machinery – that it makes you wonder if it would ever stand a chance in the stable of studios like Disney, Nickelodeon or Cartoon Network (the fact that the show is produced by DreamWorks notwithstanding). A recent Netflix launch, the animated show Oddballs, was written and developed by YouTuber James “TheOdd1sOut” Rollins, and he discussed the experience on his YouTube channel. One piece he mentioned about his experience pitching the show stood out to us regarding the feedback he got from the first executive to whom he pitched:

…the executive told me that no studio would ever want to work with a YouTuber… So, you know, not the best confidence boost ever for your first pitch.

Playing deductions here: James worked with industry veteran Ethan Banville, whose credits include a number of Nickelodeon shows. It would make sense that they pitched to Nickelodeon first and, consequently, that Nickelodeon executives were the ones who made this rather blanket comment about the industry. Netflix saw it differently, apparently, tapping into an established fan base with proven merchandising power to strengthen their animated offerings.

Appealing to a niche audience is the given, but it’s when a show goes viral that this model truly shines. Case in point: Squid Game. A Korean drama written ten years ago and largely forgotten, picked up by Netflix and produced for about $21.4 million, became synonymous with pandemic life and embodied the zeitgeist in many folks’ minds. Netflix also believes very firmly in letting their non-US content reflect native culture as authentically as possible, which made production smoother and even added to the charm of the show to its international audience; contrast Disney’s checkered track record of US-centrism in works such as Pocahontas and the live-action remake of Mulan.

The “mile wide, foot deep” style of content offering ensures that whatever people are interested in watching, there is some kind of content available to them on Netflix, and if you show it, they will watch. Netflix expanding into gaming may have been met with some scorn, but it serves the same purpose in the end: get people on the platform and show them how deep the rabbit hole goes. Gaming especially increases Netflix’s visibility on the mobile surface, a platform they have largely overlooked to date. The soon-to-launch ad-supported tiers are likely aiming at the connected TV market, a form of content delivery very familiar with advertising.

This approach is similar to Apple’s (AAPL) ecosystem, with Apple TV+ serving as the most visible “gateway drug” to get people in. The Oscar wins and critical acclaim for the shows drum up buzz the same as Netflix’s content, it’s just that Apple is willing to run it as a “loss leader” if it gets people in the door (to wit: they won’t break out Apple TV+ numbers on their financial statements). Netflix doesn’t have the luxury of treating their content this way, but they’ve clearly shown they don’t need it.

Netflix also has the advantage of not being beholden to a behemoth of a business with a reputation to uphold. Disney has thrown their weight around on political issues a time or two, especially recently, and Apple has a pattern of using their content as a soapbox to push agendas. Look no further than Tim Cook’s comments on Apple’s earnings calls saying that the goal of Apple TV+ is to “give creators a voice”.

Quantifying The Business Of Content

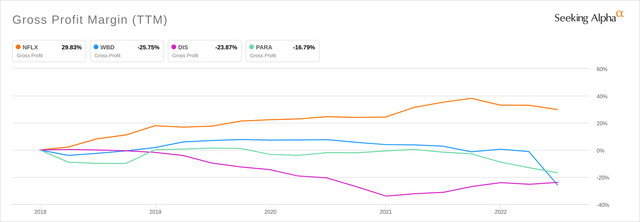

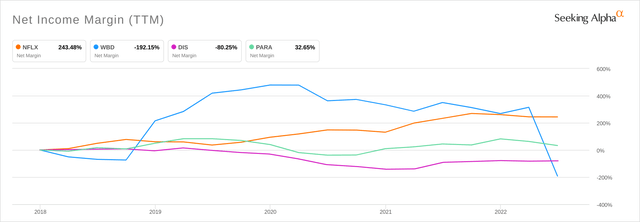

When compared to the purest-play competitors in streaming – Disney, Warner Bros. Discovery and Paramount – Netflix’s financials have truly shone over the last five years. Their TTM margins have outperformed the other three with considerably less volatility than names like Warner Bros.

Of the major Communications companies with significant exposure to streaming (who at least break out their video production costs on their financial statements – looking at you, Apple), there’s a pretty sharp divide between the businesses for whom content is their main business and not. Three names – Netflix, Disney and WBD – carry over $30B in content-related assets, mostly capitalized costs of production to be amortized, on their balance sheets. The others – Paramount, Comcast (CMCSA) and Amazon (AMZN) – have somewhere between $10-15B in content-related assets on their balance sheets.

The difficult part of assessing the competitive landscape is the heavy usage of non-GAAP metrics, by both studios and analysts, as a measure of size and health. For Netflix, that number has always been subscriber count, and the simultaneous decline of their own numbers and increase of competitors’ numbers has sounded the biggest alarm. They have responded to this issue by stating their commitment to improving value for their subscribers instead of aggressively seeking out new subscribers. This pivot makes sense, given that smash hits are not creating massive spikes in new subscribers like they may have back in 2013 when original content was… well, original. Squid Game only netted 70,000 new subscribers in North America against an existing nine-figure subscriber base, at a time when people were ripe for binge watching streaming services.

Risks

Cannibalism And Competition

Streaming is hot business now, every studio knows this, and the fight is starting to heat up. Just this week, Nielsen reported four different streaming platforms had a program with over a billion minutes watched. Streaming rights and revenues are no longer taken for granted, just look at the Disney mess with Black Widow or Paramount’s doubling down on successful creators (Sheridan and South Park creator Trey Parker) with home-grown content to seed Paramount+ while their flagship shows stream on competing platforms (Peacock and HBO, respectively). Netflix may have the inside track, but they are the only name in the streaming space that doesn’t have any sort of alternative revenue stream to cushion the costs of content production (even WBD has some in-house games they’ve developed based on their IP). Hence the push for an ad-supported tier. Since streaming rights to other studios’ content are effectively off-limits, it’s more important than ever to provide budget-friendly access to your own content in order to prevent consumers from canceling outright.

Meanwhile, Netflix’s subscriber count is starting to shrink, and they’ve finally acknowledged that practices such as password sharing are hurting their revenues. In the face of the challenging macroeconomic situation and the roaring inflation, belt-tightening is bound to happen, and streaming subscriptions may be high on the list to go. Don’t be surprised if streaming services start agreeing to bundle deals with “channel stores” from names like Roku (ROKU) or YouTube (GOOG).

Social Image

Netflix is such a presence that these days you can throw a dart at a dartboard and hit some kind of controversy. How much of it is material to their bottom line can depend on a variety of sociopolitical factors. They struggle equally with censorship of LGBT material in the Arab world and their own employees protesting and walking out over Dave Chappelle’s jokes about the transgender community in a comedy special.

Moreover, the shakeups to the pricing model and the introduction of ad-supported subscriptions can smack of desperation. Netflix has been criticized for their pricing models in the past, and given their apparent size and health, the ad revenue could be seen as money grubbing. If it makes them comparable to services such as Hulu and Disney’s ad-supported Disney+, the optics may not matter as much to the target audience (in our experience, corporate outrage seems to follow the Pareto principle: 80% of the noise comes from 20% of the population).

Moving Target Metrics

It is remarkably convenient that as soon as Netflix’s subscriber count starts to drop off, they comment how it’s not the most accurate metric anymore and that their future direction will be focused less on new subscribers and more on adding value to existing subscriptions. There aren’t good metrics for determining “subscription value,” however, other than things like churn and time spent on the platform. Netflix has also been notorious for playing their data close to the vest and mixing up how they quantify “watch time” on their platform. While “quality over quantity” makes sense, if the metrics aren’t apples-to-apples, it’s more difficult to gauge the true health of the business over time.

Content Amortization Policy

While reviewing Netflix’s data in preparing our valuation, we were trying to understand how content costs are capitalized and amortized, and the basic idea of “as people watch the show, we recognize the expenses” makes sense. However, a deeper dive on their stated amortization policy versus the amortization expenses reported on their financial statements suggests they have lengthened the average life they assign to their content. While no true motive for this kind of drift is immediately obvious, it does feel like a way to shift expenses around a la cookie jar/rainy day expenses for financial engineering. Nothing of note yet, but this is as good of a canary in the coalmine as any to pay attention to in future earnings reports.

Valuation

Let’s address the elephant in the room: we’re not going to see nearly $700 a share again anytime soon, that’s going to go down in the books alongside Cisco during the dot-com bubble. However, Netflix’s price plummet has brought them back to a reasonable earnings multiple and made them appealing enough to consider thinking long-term value.

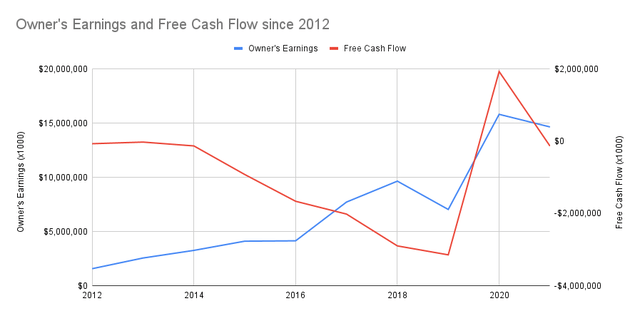

From the fundamentals, identifying the book value of a content studio’s assets is made more complicated due to the capitalization and amortization of the production costs (see above). As a result, the studios carry a large amount of content assets on their balance sheet, record new content production as non-cash transactions, amortize previous production costs as large non-cash expenses on the income statement, and show comparatively small changes on the cash flow statement compared to revenue. We aren’t sure whether “content acquisition costs” as listed on Netflix’s cash flow statement should be deducted from their owner’s earnings total. Our opinion is to treat those costs as separate from owner’s earnings and capital expenditures; they make sense to include in free cash flow as operating expenses, but for owner’s earnings, which represents the cash available to reinvest in the business, content acquisition is their business, purchasing content assets is reinvestment. We have typically stuck to this line of thinking when evaluating “business expenses” on the Cash Flow statement.

In terms of owner’s earnings, Netflix’s growth has been nothing short of remarkable. Their most recent year’s owner’s earnings came in at $14B on a market cap of just under $100B; for reference, we consider an FCF-to-market cap of 8% to be above average. The aforementioned caveats about content asset acquisition and amortization are still active, especially considering the stark difference between owner’s earnings and free cash flow over time; note that FCF has been predominantly negative since 2012, when original content production took hold:

Netflix’s owner’s earnings have a historical long-term CAGR of over 30%; this growth is clearly unsustainable. They expect amortization in FY22 of $8.7B, and we will model revenues as flat year over year, $5.1B, capex at $550M, and the change in working capital at +$700M for a grand total of just under $14B. Between Disney, Paramount and Comcast, the long-term CAGR in this industry appears closer to 5-6%, so we will pessimistically use that for their growth moving forward.

With the modeled stunt to their growth, right now Netflix is pricing in a discount rate of around 20% according to the Gordon model. Comcast’s discount rate is about 16%, and Disney is around 11% (with a bit of adjustment since their most recent year’s owner’s earnings is negative). Given inflation and economic forecasts, we likely need to increase our risk-free rate to give a hurdle of about 14%, meaning Netflix is currently pricing in a 6% risk premium. With Comcast’s 2% premium, Netflix would have 40% upside and be valued around $315/share, right around an earnings multiple of 30x.

Conclusion

The market continues to oscillate wildly around Netflix, first feverishly overvalued then back to mildly undervalued in a short period of time. As a business, however, their earnings are growing healthily and steadily, their costs are under control relative to their peers, and they have plenty of content on their balance sheet to continue trawling for the next big hit. The competition is growing, though, and Netflix will need to find some kind of competitive advantage beyond just the content to maintain the trajectory they’ve been on. Even if they can’t maintain that trajectory and end up settling into the groove of other entertainment names, there’s some meat on the bone at this point.

We’ve been watching Netflix for some time as part of a themed basket of securities in our portfolio focused on what we call “next-generation entertainment.” Their valuation always felt too out of reach for us to make a move, so in the meantime we took a position in Disney as an entertainment mainstay with the guns to disrupt whatever they wanted to. Now, however, Netflix is starting to reach a point where if they near that nice round number of $200/share, we’d consider initiating a position and seeing what happens next for them. Even if they don’t get there, we may just call it good enough. They’ve proven they can pivot and innovate before, we’re pretty sure they have the capability to do it some more.

Editor’s Note: This article was submitted as part of Seeking Alpha’s best contrarian investment competition which runs through October 10. With cash prizes and a chance to chat with the CEO, this competition – open to all contributors – is not one you want to miss. Click here to find out more and submit your article today!

Be the first to comment