pcess609/iStock via Getty Images

Our Funds’ Distribution Sources: How Stable Are They?

[This article was originally published May 21, for members and trial subscribers of our Inside the Income Factory service.]

Our Income Factory strategy rests on the idea that (1) an asset’s value (be it a stock portfolio, a manufacturing plant, an office building or shopping center, or an oil well, etc.) depends on its ability to generate cash income over time; and (2) as long as it is doing that, then the short-term re-sale value the market puts on the particular asset is pretty irrelevant.

This all assumes, of course, that our stocks or funds keep paying their distributions, or that the tenants of our office buildings and shopping centers keep paying their rents, or our oil wells and factories keep producing, etc.

In the high-yield markets that we participate in – closed-end funds, business development companies (“BDCs”), etc. – that means focusing on the distribution stability of our funds and other investments. That requires us to look closely at the source of those distributions. Especially, we want to see whether the distribution depends on largely predictable, “business as usual” income sources; or whether it depends on more than just “business as usual,” and instead requires performance that is more “heroic” or dependent on factors outside the fund or corporate management’s control.

Sources of Distribution

The “business as usual” sources of income that a fund receives and can then use to pay its distribution are dividend and interest payments on the stocks, bonds or other financial assets it owns. This income, minus the fund’s operating expenses, is called Net Investment Income (or “NII”).

The other component of a fund’s earnings is made up of the capital gains (or losses) on its investment portfolio. This is the appreciation or depreciation in the market value of its assets, and is all part of a fund’s earnings.

These two sources (NII, or cash received from dividends, interest and other distributions, minus expenses) plus capital appreciation (or depreciation), added together, are the “total return” on an investment.

Closed-end funds, as well as similar “investment company” type entities, like BDCs, have to cover their distributions from one or both of those two sources: (1) Net Investment Income (“NII”), or (2) capital appreciation. If they don’t, they will erode their capital base over time, essentially paying out more than they earn, and their investors will see their principal shrink over time (like owning an annuity), even though they may be quite happy with the distribution flow, as long as it lasts. (We’ve discussed this topic at length: here and here, for example.)

Some closed-end funds, as well as practically all BDCs, own mostly credit assets (loans, bonds, other fixed income like preferred stock or convertible bonds) and therefore earn virtually all of their own income in the form of interest or dividends. That means the income they rely on to pay us our dividends or distributions comes from relatively steady, “business as usual” sources.

Funds that own stocks live somewhat more dangerously. Many stocks, especially “growth” stocks of the sort most equity funds own, only pay dividends of about 1 or 2% (or less). That means the funds that hold them and pay dividends of 6 or 7% or even more, are counting on their ability to generate capital gains of at least 5 or 6% per year to make up the difference between the dividends they receive on their own investments and the ones they pay out to us.

Managed Distributions: Advantages and Disadvantages

Since capital appreciation doesn’t occur as steadily or predictably as interest and dividend payments, equity funds don’t have as steady an income flow as credit and fixed-income funds. Knowing that closed-end fund investors like steady income flows, even from their equity funds, many equity funds try to “smooth” their payments by adopting a “managed distribution” plan. That’s where they pick a percentage distribution yield that they believe, based on their experience, they can meet over time, even if there are some peaks and valleys between their actual month-to-month cashflow and earnings, and what they pay out to shareholders.

Let’s look at Royce Value Trust (RVT), a highly regarded closed-end fund that has earned an annualized total return of over 10% for the past 35 years. A very distinguished record. It pays a minimum dividend based on a “managed distribution” plan of 7% of a moving average of the fund’s net asset value over the trailing 4 calendar quarters. Its average yield over the past 4 years has been about 8%, but its current distribution is up to almost 10%, not because of increases in the distribution, but because the stock price is down by 25% so far this year.

Here is the problem. Managed distributions seem fine to me as long as they are just leveling off “peaks and valleys” in a fund’s earnings. But if it’s all valley and no peak for a long period of time, and the price of the fund keeps dropping, then every “managed” distribution is being generated by selling off more of the fund’s capital at a lower price.

One of the reasons many of us like our Income Factory strategy is because, if we’re retired, we can collect our high distributions and live on a portion of it, re-invest the rest, and know we haven’t touched our principal. (Unlike many retirees with “growth stock” portfolios that have to routinely sell off a portion of their principal to generate cash; and hate doing so, especially when prices are down as they are at the moment.)

So when I see funds like RVT, dropping in price but “managing” to pay their large distribution by apparently selling off assets that have dropped in price, I become concerned. Obviously RVT and its creator/manager (Chuck Royce) have a splendid record and have come through other downturns with flying colors, so I am inclined to want to stay invested. But I don’t want to be taking money out of the fund if it means selling off assets during a market down-cycle.

Easy Solution: DRIP

I don’t normally do automatic dividend reinvestment, preferring to reinvest and compound my distributions myself, typically being opportunistic and looking for bargains. But at times like this, for equity funds that I want to remain invested in because I trust management, and want to be sure I’m not taking capital out of good funds that I want to remain in for the long term, I am inclined to put funds like this on automatic pilot to be sure my distributions stay in the fund and compound at the current low price.

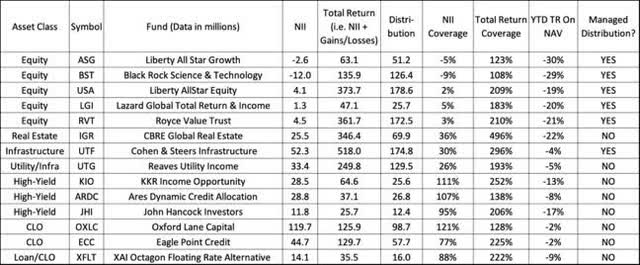

If we look at a representative sampling of closed-end funds that we own, either in our model portfolios or in my (and many members’) personal portfolios, we’ll see that the RVT example is not unique.

Notice how our equity funds generally have really taken it on the chin this year in terms of their own total return measured on their underlying net asset value. That means they can’t be achieving any overall capital appreciation, and we can see in the coverage figures (the first five columns of numbers, taken from the most recent annual report) that they need capital appreciation to cover their distributions.

Let’s look at Liberty All-Star Growth (ASG), a fund with an excellent long-term record. But notice that its NII coverage (i.e. interest and dividends, etc.) of its distribution is actually negative. That means its interest and dividend income (even in a good year like 2021) doesn’t even cover its expenses, so it is totally dependent on capital gains. It obviously is good at generating capital gains, since last year it managed to cover its distribution by 123%, when you include its capital appreciation. But since we know it isn’t repeating that capital appreciation experience this year, then it must be paying its distribution out of its existing capital, which means selling off assets at current depressed prices.

This same trend is apparent in most of the other equity funds, whose NII coverage of their distributions is minimal and all count on capital appreciation (the column labeled Total Return coverage) to cover their distributions in more normal times.

Meanwhile, our credit funds – Ares (ARDC), KKR (KIO), John Hancock (JHI), Oxford Lane (OXLC), Eagle Point (ECC), and XAI Octagon (XFLT), all (1) cover all or most of their distributions from their “business as usual” (i.e. NII) income (interest mostly), and (2) for the most part have not dropped as much as the equity funds.

In the middle we have equity funds in the utility, infrastructure or real estate sectors, like Cohen & Steers Infrastructure (UTF), Reaves Utility (UTG) and CBRE Global RE (IGR) that, while they are still equity funds, cover somewhat more of their distributions from interest and dividends, or rental income (all “business as usual” income) and are less dependent on capital gains. Most of them haven’t dropped as much in total return this year as the equity funds either.

Bottom Line

If we are reinvesting our distributions and compounding at the prices these equity funds have dropped to, then I am not particularly concerned. But I would not want to take money out of these funds permanently, at the current prices they must be selling assets at to pay their “managed” distributions. So if we have a choice of which distributions to keep and spend and which to reinvest, I’d keep and spend the ones from our credit funds where we know the fund isn’t invading its principal (much or at all) at depressed price levels to pay the distribution.

This also confirms to me, once again, that credit funds in general, especially now at a time when so many of them are paying higher yields than they have in a long time, are the better bet in periods of uncertainty and volatility.

I’m not suggesting any sort of wholesale move out of equities, which definitely have a place in our portfolios, but am merely:

- Pointing out the dangers of taking money out of some equity funds, even if it’s labeled as a “managed distribution,” if we have a choice to keep it in the fund by reinvesting and compounding it;

- And suggesting we take whatever money we have to take out of our portfolios from funds that are paying it out of current, “business as usual” income, and not eroding their (and our) principal in order to do so.

Hope this is useful and/or interesting. I look forward to your comments and questions.

Be the first to comment