Edwin Tan /E+ via Getty Images

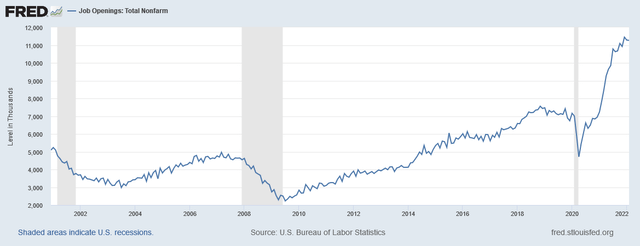

Earlier today, a friend texted me, asking if there really was a labor shortage. To answer that question, we need to look at several sets of data, starting with JOLTS (Job Openings and Labor Turnover).

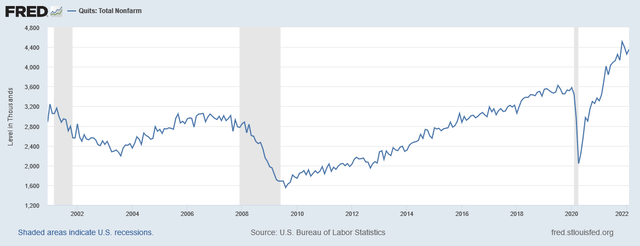

First, note that there are only a little more than 20 years of data. From an economic perspective, this is still very new. But given that limitation, we can say with confidence that total job openings are very high.

The number of people quitting jobs is just shy of a series high, indicating people are walking off the job in near-record numbers.

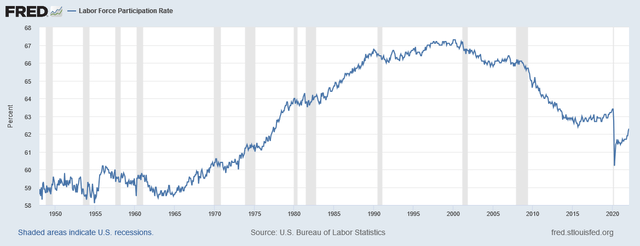

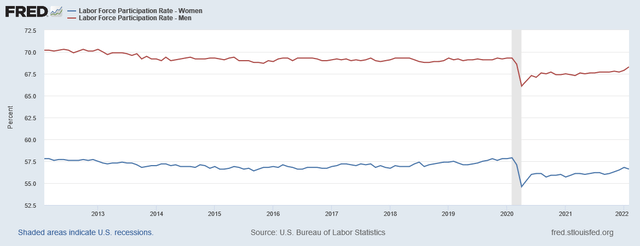

Next, let’s turn to the labor force participation rate (LFPR) to determine the size of the current talent pool:

Labor force participation rate (FRED)

The LFPR adds the number of people employed or actively looking for work and then divides that by all the people that could (theoretically) be working. The LFPR has been declining since the end of the 1990s due to baby boomers retiring. However, the LFPR dropped sharply in the last recession and has yet to regain previous levels.

Before the recession, the peak for women’s LFPR was 57.9% while that for men’s was 69.3%. Now each is 56.6% and 68.3%, respectively. So, both men and women are still out of the labor force.

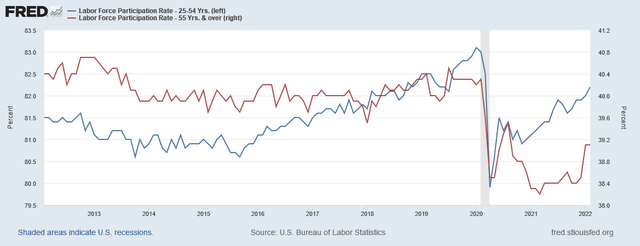

Let’s look at the data from an age perspective:

LFPR for two age ranges (FRED)

The LFPR for 25-54 years (in blue, left scale) and 55+ years (in red, right scale) are still below pre-recession peaks.

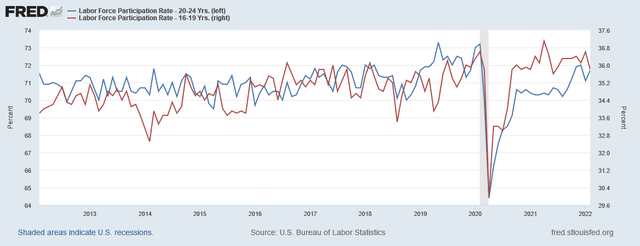

LFPR younger age brackets (FRED)

But the LFPRs for younger ages have returned to pre-pandemic levels

The data tells us there’s a huge demand for labor, as evidenced by the JOLTs data. The main age groups that are still out of the labor force are older.

There are a number of reasons for this. People are still caring for family members due to Covid. There is also still concern about the virus. But we’re also in the middle of a great realignment within the labor market. A number of articles have noted that the pandemic taught people that life is too short to put up with what they view as unattractive work conditions.

We’re seeing the results of these decisions as frontline workers in health care, child care, hospitality and food service industries, pushed to the brink of human endurance, decide that the grueling hours, inadequate pay, lack of balance and abuse by employers and clientele are no longer acceptable trade-offs for their mental and physical well-being. Restaurant signs urge patrons to “be patient with those who showed up to work” because they can’t afford to lose any more workers to abusive customers.

This article (link), written in response to the previous citation, offers additional anecdotal stories as to why people are quitting. And, it’s not just occurring in the United States.

And underlying all of this is the continued retiring of the baby boomers, a trend that will continue.

So, to answer the question, there is a labor shortage. Part of it is caused by demographics – an aging population means increasing retirements, lowering the number of people available to work. But there’s also a mismatch between workers’ and employers’ expectations. That may take some additional time to work out.

Be the first to comment