courtneyk

I recently wrote an article to illustrate that, over the long term, there can be value in constraining the volatility of your portfolio. But how to achieve that? In this article, I’ll cover tactics I use to diversify my portfolio and other exciting possibilities. Hopefully, this shows that diversifying a portfolio can be achieved beyond adding a company in another industry.

The first thing that will come to mind is to take a closer look at securities that generate returns while exhibiting less volatility. This is called low-volatility investing. It is considered a factor (a specific driver of returns), and funds are focused on harvesting its premium. I like it; a few stable, boring building blocks that generate sound returns are precious.

But one important thing to realize is that we merely need to manage volatility at a portfolio level. Individual securities can exhibit a lot of single-name volatility and still help to bring portfolio volatility down…

True, most companies don’t.

There’s an old market adage that goes something like: “in a crisis, all correlations go to 1.”

It is meant to convey that correlations change when there is a big crisis in the market. In practice, everything is getting smashed and only safe haven assets like the Swiss franc, USD, gold, etc., are catching a bid.

It can be very frustrating, as even stuff that shouldn’t suffer from the crisis gets sold. Market participants often deleverage (sometimes forcefully), selling whatever they can instead of what they’d like.

It is essential to realize that both volatility and correlations are unstable. You may have 20 years of data on certain assets showing a negative correlation, but it doesn’t have to hold in the future. Many traders/investors have blown up, not counting on how wacky things can get.

I try to generate consistent returns that aren’t as dependent on the market. I am still fairly heavily betting on beta, though. I’m not sure I generate enough alpha to hedge out all market risk (long-term returns could be meager). In addition, sometimes it is costly (transaction costs, borrowing costs, interest on margin, margin capacity, etc.) to hedge out the risks I’m not interested in.

In October 2022, I prepared a presentation for Dutch investors. I put together some risk/return statistics about an account I manage. I’ve copied these below to illustrate what investment style does for me. My returns haven’t been spectacular, although they are slightly understated, as I hold many contingent value rights at nominal or zero value (like the BMYRT).

| Account X | VTI | IWN | |

| Return | 37.57% | 36.92% | 16.36% |

| Max drawdown | 22.98% | 24.50% | 44.62% |

| Standard deviation | 1.12% | 1.43% | 1.8% |

| Correlation | 0.2 | 0.23 |

Four years in, I’m reasonably happy with the results. It has been an uphill battle with small-cap value so out-of-favor, although that factor is coming back of late. At the same time, I’ve made plenty of mistakes, and it is always hard to forgive yourself.

The standard deviation of my portfolio has been modest compared to a worldwide all-cap index. My most significant drawdown has been only slightly smaller. I’d argue I allowed this drawdown to get so significant from a high. Perhaps this isn’t correct (I’m not sure), but I’m inclined to have more capital at risk when I’m doing well, all other things equal.

I like that I’ve generated this modest but satisfying return with a very low correlation to major equity indexes. In March 2020, as markets finally collapsed because of Covid-19, I was up double-digits instead.

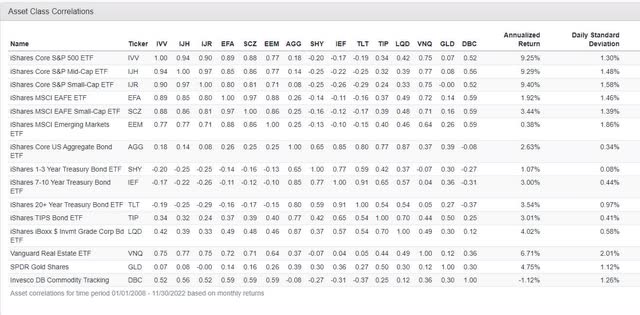

The correlation to the S&P 500 (SP500) is in the same ballpark as the indexes mentioned above. I’ve pulled a correlation matrix from Portfolio Visualizer to put this into context. This level of correlation to the S&P 500 corresponds with an aggregate bond index (corporates and treasuries mixed). Of course, that doesn’t mean my portfolio correlated with the bond index or had a similar risk profile. It’s just that performance has felt as different as a bond index to the S&P 500.

asset correlation matrix (portfolio visualizer)

If you’ve looked at the level of correlation between asset classes, it also becomes clear how hard it is to achieve these low levels of correlation AND sustain an equity-like return. Of course, it is easy enough to generate a bond-like correlation by investing in bonds; the problem is it offered (things are changing) barely any return over the past four years.

Interestingly, over this entire period, except the tail of 2020 and 2021, I’ve always had quite a bit of exposure to many companies that were straight-up value selections. Often without any special situation angle.

But I also added takeover targets, SPAC’s and SPAC derivatives, shorted equities and bonds, distressed debt, debt, closed-end funds, utilized options, held spinoffs, and I’ve been an avid collector of contingent value rights. All of which fall under the special-situations umbrella.

Sometimes I’ve been only 80%-90% invested, but most of the time, I used leverage and increased exposure quite a bit beyond 100%. That may sound risky but my portfolio never behaved risky as a whole. I should likely have been a bit more aggressive.

For example, pre-deal SPACs (if you buy them cheap enough) are a package of short-dated treasuries with a free option. These are some of the least risky things I’ve ever invested in. They are not as attractive anymore because the option isn’t as valuable anymore as the party around these has quieted down a lot.

If these things all sound very complicated, that’s understandable. Looking back, one of my mistakes over the past few years is that I ran an OVERLY complex portfolio. One of my goals for 2023 is to keep things more straightforward in the future but maintain the advantages of my investment style.

This is all a long-winded way of saying that when I look at investments, I’m very interested in:

Does this improve my portfolio in terms of risk-adjusted return?

while, of course, considering:

What is the risk/reward of this investment?

I believe an investment doesn’t always have to have an enormous upside if it helps to diversify my portfolio.

In value investing circles, there is a notion that diversifying beyond 20-30 stocks doesn’t help you much while you are “diworsifying”(a Buffett-ism) from your best ideas. After all, great ideas are scarce.

Many papers argue something to that extent (like this one.)

The problem is that these studies often randomly add stocks together and measure whether diversification increases. Alternatively, they try to achieve diversification but through fairly basic diversification ideas (industries, size, etc.). True, most stocks are highly correlated. But some stocks differ from most stocks and sometimes even from each other.

Think about early-stage biotech. What drives its share price? These things live or die by the results of clinical trials. These are discrete events; when one occurs, a stock can crater or moon. The ebb and flow of the economy doesn’t impact a stock like that. If you add one of these to your portfolio, it is almost surely going to diversify your other 30 stocks. This doesn’t hold as well if you already hold a lot of biotech stocks, of course. Although the events are discrete, there are times that money flows in and out of biotech, and moves will be highly correlated.

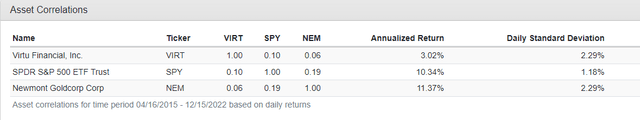

Other examples are mining & exploration companies. These live and die-by-drill results… Same idea as the biotechs. Two practical examples of stocks with very low correlations to major indexes are Virtu Financial, Inc. (VIRT) and Newmont Corporation (NEM):

Asset correlations (Portfolio Visualizer)

Around 25% of my portfolio is invested in mergers & acquisitions. I plan to raise this percentage as the group looks quite attractive. If you invest in every takeover of a public company, you can find the yield-to-close is likely well above 12%. I don’t advocate that, though. Also, the average gets lifted by mergers that are less likely to close. I wrote this in December 2022, and practical examples would be F-star Therapeutics, Inc. (FSTX), Sierra Wireless, Inc. (SWIR) and Euronav NV (EURN). If these deals don’t go through, the stocks involved tend to drop a lot. But there are plenty of good deals that yield between 6%-12% to close. These are generally much less likely to break. Returns of merger candidates would appear to depend on deal-specific drivers mostly.

Indeed, these do a lot to diversify my value stocks. However, at times they do move as a basket. Leveraged operators often hold these merger targets-specialist traders and arb funds etc. If an event causes hedge funds to deleverage, arbs can move in a concerted way. Companies also tend to walk away from deals if credit windows close, equity markets get slammed or the economic outlook suddenly deteriorates forcefully (think March 2020). This can suddenly cause a widening of spreads across the merger universe. If you are concentrated

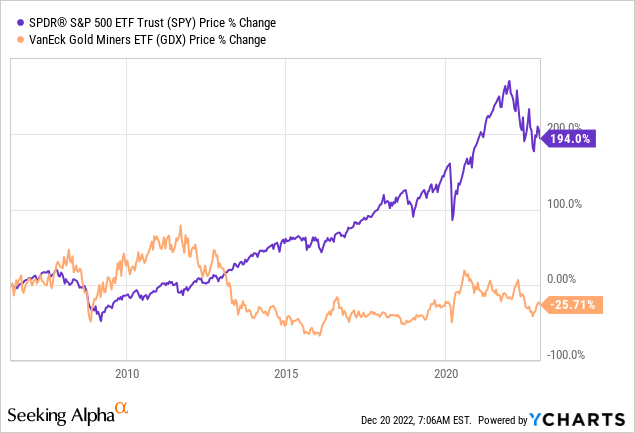

I’ve just given examples of pockets of the market where it is possible to find stocks that above average idiosyncratic risk and below-average systemic risk in the context of the entire stock market. One thing to keep in mind is that this is not a secret dynamic. The market realizes there’s value in idiosyncratic risk vs. systematic risk and therefore bids up the prices of these securities. Otherwise, the diversification would be an entirely free lunch. Many investors struggle to invest in mining and biotech, and as a whole, these sectors tend to underperform. However, if they didn’t underperform, these would be a must-have. The more idiosyncratic an industry, the harder it gets to squeeze out returns (see the GDX graph).

There are many other ways as well to improve the diversification of a portfolio. I’m, for the most part, a value investor, but I’m cognizant that my portfolio would likely benefit from including momentum. Even before I’d taken note of the academic/quant ideas around combining value/momentum, I noticed things I was buying (as a deep value investor) were often doing poorly in the months after. At the same time, when I sold, as stocks appreciated through my assessment of fair value, they would often continue to do well for some time. Frustrating, to say the least. I think this happened because I never even considered momentum.

It is beyond the scope of this article to cover every possible way to diversify a portfolio effectively. Still, I did want to point out that adding something like a trend-following allocation to a portfolio could also work.

Conclusion

I don’t put together my portfolio based on attractive risk/reward propositions. With new investments, a vital consideration to me is how they will likely interact with my portfolio in the future. Less attractive risk/reward profiles can still be treasured if they’re genuinely diversifying or diversifying in a beautiful way. There are rare examples of companies that will trade up as most stocks are crashing due to systematic risk. Special situations are generally quite attractive because, almost by definition, these are heavily dependent on idiosyncratic risks.

Be the first to comment