http://www.fotogestoeber.de

The market has fallen 11% since I wrote my last article in April about a market crash ahead. Since then, the macro situation has worsened. YTD, the S&P 500 (SPX) has returned a harsh -17%, but there is likely more pain ahead. Many factors suggest a longer drawdown, and dip buyers should exercise prudence when buying the index. In this article I propose a new way of looking at risk-neutral implied volatility, and risk premium. I also explore the implications of a strengthening dollar and the diminishing stability of the global economy.

Risk Premia and Volatility

A risk premium is the expected excess return of risky (read: volatile) assets over the risk-free rate. People are generally risk averse, meaning they prefer some certain return that is less than the expected value of some uncertain return. This is like preferring to not bet when one can take a bet where the odds are in one’s favor. Risk premium arises because a marketplace of risk averse individuals will naturally shun riskier assets, thus underpricing them and creating an opportunity for other investors to earn a “risk premium” by investing.

It’s important to note that risk premia are different for different assets at different times. Furthermore, an asset class’s risk premium tends to smooth out and ignore idiosyncratic risk. For example, the risk of a more volatile stock is not necessarily compensated for. In the capital asset pricing model (CAPM), a higher volatility is expressed as a higher beta and this is multiplied by the equity risk premium to get the expected excess return over the risk-free rate. Nothing else is added which is specific to the stock, so the stock’s idiosyncratic risk is uncompensated in the model.

Based on this, asset classes have individual risk premia, but the meaning of risk premia diminishes once we look at individual assets within asset classes. This is consistent with the logic of passive index investing—one cannot beat the market in the long run because the idiosyncratic risk of different stocks within an index are not compensated for. The best we can do is the market’s risk premium. Extensions of the CAPM model may use more factor betas (the famous ones being Fama-French three and later five-factor models), but these extensions do not detract from the point that it is still various kinds of risk premia running the show.

So riskier asset classes tend to be compensated more. This too aligns with what we observe. Equities have higher volatilities than corporate bonds and equities have a higher long run CAGR. Also, at any given moment, there is both a historical premium of equites (or corporate bonds) over the risk-free rate, as well as a forward-looking, market-implied premium.

The historical premium is simply the de facto equity index return over some period minus the prevailing risk-free rate over that same period. The implied premium is harder to calculate, but it is some amalgamation of the current index price, the current risk-free rate, and some consensus expected cash flows of the index. These inputs are used to derive the risk premium the market “currently estimates.” Where this gets interesting is by bridging this concept to asset class implied volatility. For the remainder of the article, I will only discuss equities as the risk asset of interest.

Equity implied volatility (IV) is calculated from option prices. With a single option, the IV is a standard deviation of annual returns which results in the observed option price, assuming returns are normally distributed. However, different options imply different IVs and that is problematic if we want a single number.

A better way to find IV is to use many options. For that, the VIX formula uses a list of liquid SPX options to back out a risk neutral implied volatility of the index. (Risk neutrality means that certainty has no additional value to an individual—he or she is indifferent between a certain return and an uncertain return with the same expected value as the certain return. Think of this as being indifferent between betting at the “fair” odds and not betting at all.) VIX is the option market’s estimate of “fair odds” index risk.

If risk premium compensates one for taking risk, its magnitude should move together with the perceived risk level. Thus, equity risk premium (ERP) should move with equity risk. Stated differently, the VIX and implied ERP should be highly correlated to each other. Notably, this correlation is probably more of a causation, where higher risk leads to a higher risk premium being assigned.

Implications of this Result

If this result is valid, it would be a completely ex-ante explanation for the efficacy of buying the dip. Normally, the argument for buying on dips is backward looking and extrapolative. Along the lines of “it has always worked so in the future it should continue to work.” This is an ex-post phenomenon, which limits its value in the forward-looking fields of finance and investment. Disclaimers of “past results are not indicative of future performance” get at the heart of this matter.

In contrast, an understanding of the VIX as something that closely follows the elusive ERP means that buying during VIX spikes (which usually occur in market dips) is really locking in equity when its risk premium is higher. This is completely forward looking and gives a causal argument for why buying dips can be a winning strategy—a simple ex-ante explanation which does not fallaciously extrapolate historical results to the future.

A very relevant extension is the volatility risk premium (VRP). VRP is generally defined as the tendency of IV to be greater than the realized volatility (RV) which follows. It tends to favor option sellers (who are short volatility) over option buyers (who are long volatility). Occasionally RV can far exceed IV, which severely hurts the sellers. This is why option selling is sometimes viewed as picking up nickels in front of a steamroller.

But taken literally, the VRP can be understood as “the risk premium earned as compensation for taking on a volatility investment,” the same way ERP is the risk premium earned as compensation for an equity investment. Before continuing, I should first make clear that there is one major difference between equity and volatility investments: volatility is zero-sum, and equity is not. The only way to participate in volatility is to use derivatives. Each derivatives trader has a counterparty. A trader’s gain is always his counterparty’s equivalent loss (ignoring transaction fees). The total money in the system does not change. Equities are ownership in firms which create useful things. They innovate and grow. Economies comprised of innovative and profit-seeking firms can make the total pie bigger over time. The effective money in the system is unbounded because monetary velocity can increase with more real output, even if money supply stays constant. Therefore, while ERP and VRP both say “premium” it’s easy to see that only equities would have a long-term positive premium while VRP would probably average out to almost 0 over a long period of time.

With VRP, the VIX of VIX Index (VVIX) has new meaning. VVIX is derived from using the VIX formula on VIX index options to find an IV for the VIX. Thus, if the VIX as an estimate of equity volatility is related to the ERP, then the VVIX as an estimate of VIX volatility is related in the same way to VRP. To be clear, taking “risk” in the sense of volatility, and thereby earning the VRP, should entail shorting it. This matches with going long equities for positive exposure to the ERP because in both cases, the risk is compensated by intermittent cash flows. Equity holders earn dividends and option sellers earn option premiums. Put another way, generally equities do well and generally option selling do well. The risk premium accrues to positions which are vulnerable to the outlier, fat tail events.

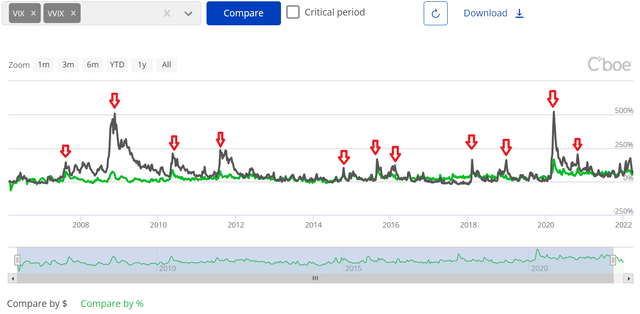

Under this paradigm, the similarity between ERP/VIX and VRP/VVIX get even clearer. Again, since the VIX and ERP move together, buying equity at higher VIX levels is effectively locking in a higher ERP on an equity investment. This model is supported by the data we observe: VIX spikes tend to come from market dips and those, in hindsight, have always been good buying opportunities. Likewise, shorting volatility at higher VVIX levels is locking in a higher VRP on a volatility investment. VVIX spikes tend to occur when VIX increases. Due to volatility’s tendency for mean reversion, elevated VIX levels have always been the more opportune moments to sell equity options and VIX futures. In both cases, we know ex-ante what should happen, and the ex-post historical data tends to agree.

Breaking Ceteris Paribus: The Importance of Relative Risk

Throughout the article I was very careful to say that ERP moves with the VIX, but not that ERP and VIX were the same. Also, it is probably incorrect to assume that a percent change of the VIX will be met with a linear percent change in the ERP. In fact, that should only be the case if “all else were equal.”

Investors deal with opportunity costs and a constantly changing world. Therefore, an IV increase is one part of the picture for finding the true risk premium, albeit a very big part. In reality, different asset classes will have their own IVs (simply use the VIX formula on the index options of some asset class) so the market perception of risk is not limited to US equities and the volatility indices which matter will not be limited to the VIX.

A more robust measure of U.S. ERP needs to account for the VIX relative to the IV movements of alternative asset classes. This means the IVs of bonds, commodities, and foreign equities. If the IV for these alternatives are increasing at the same pace as the VIX is increasing, then US equity risk has not really increased relative to the other choices. In relation to everything else, US equities remain in the same “ranking” by risk. Therefore, there is no reason for US equities to suddenly receive greater compensation for risk when compared to the other assets.

Now suppose the VIX was rising but other IVs were rising faster. Now, instead of a rising or unchanged ERP, I would expect the U.S. ERP to drop. Even though U.S. equities have gotten riskier, relative to everything else it has become safer. Therefore, the risk premium should decrease.

Of course, this “relative risk” addendum is what makes things much harder to quantify. For one, what exactly are the different asset classes? Not all of them will even have an index or, if they do, they might not have index options. The options which do exist may be too illiquid for the VIX formula to yield a meaningful result. Also, what is the existing standing of relative risk? The true forward-looking ERP remains elusive. But we’ve covered useful ground to look at what is going on today.

What We See Today and Why It’s Problematic

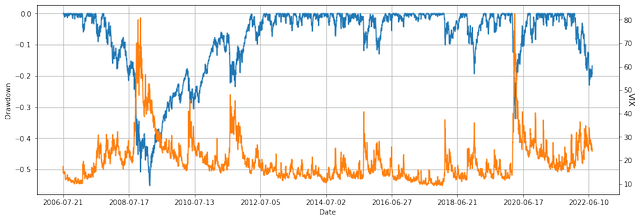

My pessimism about the next year of SPX returns begins with the logic above. SPX is down quite a bit YTD, but the current VIX is not really that high. This suggests the market is not assigning a high ERP to equities right now. In the past, the VIX has gotten higher from smaller SPX drawdowns. I would also expect the growing macro issues to lead to more uncertainty which pushes up option prices and the VIX.

SPX Drawdown & VIX Overlay (Price data from Yahoo! Finance; Calculations by Author )

The fact that things are fairly calm is concerning. Furthermore, the VVIX is also extremely low. Generally, when the VIX spikes, the VVIX follows. Given the VIX’s 45% YTD increase, it is hard to understand why the VVIX is down as much as the SPX this year.

In the context of risk premia, this development means the VRP is starting to shrink and option sellers need to beware of sudden and much higher realized volatility, which is almost always initiated with a downward move in the SPX. In summary, as ERP is coming out lower than one would expect after a large selloff, the market also suggests that volatility is underpriced.

Finally, my biggest area of concern comes from the impacts the strengthening dollar and America’s production base might have on the volatility and risk premia around the world. It’s no secret that the U.S. and Western economies have become more service oriented as production of physical goods have been offshored to foreign countries with cheap labor. Raw material and commodity extraction have also mostly been done abroad, despite America having the natural abundance to do it locally. This trend of outsourcing everything but the services which organizes labor and physical capital has been happening over the last fifty years. Today very few goods are produced completely within the country. Therefore, the U.S. has a very high dependence on the stability of the rest of the world.

US inflation today was mostly driven by money printing in the last two years, government stimulus programs, supply chain issues from the pandemic, and supply shocks from the war in Ukraine. In other countries, the situation is even worse. Anyone can see the situation is worse outside of the U.S. because of the dollar’s rise against other currencies as seen in the U.S. Dollar Currency Index (DXY):

In a way, this rise should be reassuring because the world still sees USD as the ultimate haven. Despite U.S. inflation, the ever-growing national debt, and currency debasement via printing, USD is still considered better than everything else. But the scramble into dollars is indicative of the issues other countries are having. There would not be such high demand for a safe-haven asset otherwise.

Unfortunately, a strong dollar makes preexisting inflation worse for foreigners. Because so many things are priced in dollars, foreigners experience a price hike due to their currency’s falling exchange rate against USD. It’s likely that inflation was already bad (which was why people were buying dollars), but now a stronger dollar makes things much worse for consumers in other countries.

This comes back economically because these other countries are where Americans get much of their goods from. A worsening economy in these producer nations will negatively impact supply chains, which will exacerbate US inflation.

And here’s the worst part. If U.S. inflation persists, then U.S. nominal rates will need to rise. This would likely come from the Fed’s rate hikes. But higher U.S. interest rates makes U.S. assets more attractive, which will mean more demand for dollars to buy U.S. assets. This will make the inflation outside of the U.S. even worse as USD strengthens even more. The feedback loop that ensues can be resolved in a few ways. One is if other central banks raise their rates such that U.S. assets look less attractive. Another is for countries to stop pricing in USD. Both have strong implications for global risk premia, but the second is unlikely and would also be disastrous for America.

Returning to risk premia and volatility, I see the economic situation in other countries (particularly in Europe) as much worse than in America. Therefore, while the VIX has risen YTD, the equity volatility indices for other countries will have increased by much more. On a relative basis, US equity appears to command a much lower ERP than before—it is not a great time to buy.

Conclusion

I have mostly been buying REITs and high cash flow stocks, favoring inflation-resistant industries. When the ERP seems unattractive, it doesn’t make sense to buy broad indices. A strong case can be made for implementing a barbell strategy. One could select value and quality stocks but also get small exposures to leveraged long funds of high beta sectors which have been beaten down (semiconductors). A meaningful change in sentiment or the macro situation would send these funds soaring.

Though I love options and have written about and used them as hedging tools, I do not think long puts would be a good move right now either. I believe the SPX will be headed a longer way down due to economic headwinds that do not seem to be priced in. However, the time frame for this drawdown could get very long. The decline this year has dragged on for over two fiscal quarters. Options with tenors that long have less convexity, which reduces their value as a hedge.

Based on how low the VVIX and VIX are, I do think that VIX calls 30-60 DTE with strikes above 50 could be considered. It’s possible the market is waiting for a pivotal, “Lehman Brothers” moment which will immediately be followed by a surge in volatility and a quick descent to a more attractive entry point.

Be the first to comment