steved_np3/iStock via Getty Images

Everyone seemed to expect that it was coming, and nearly every industry ‘[f]rom carmakers to refiners’ were bracing for its impact according to the Associated Press. The AP explained in its Thursday, September 15th article, From carmakers to refiners, industries brace for rail strike, some life-altering changes might come to US consumers and businesses alike if a (national) railroad strike occurs…”

– Introduction of an article I submitted for editorial review on September 15, 2022.

I first learned of a looming railroad strike in a segment on Varney & Co. on Fox Business and several other news programs in early September, just days before the initial strike deadline of September 15th. Recognizing the potential impact of such a strike, I began an article but didn’t want to sacrifice the quality and content required to publish so fast, so I ultimately did not publish my work. I’ve been following this saga in the months since the initial agreement – and it is anything but over.

The series of events, discussions, and negotiations offer interesting insight into how unions and society at large are changing, for both better and worse. There is a shift happening in the behaviors, thoughts, and beliefs of those living in America, and its ripple effects will likely touch every corner of the U.S. economy.

For instance, The American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) explains on their website that:

The pandemic laid bare the inequities of our system. Working people want safe jobs with good health care, flexibility, sick leave, and where they feel respected and valued. Working people feel a new sense of power and leverage. They’re looking at work in a different way.”

While this may or may not be a long-lasting shift, it is certainly of note that these ideas seem to be resonating more with the American population than at any time in recent memory.

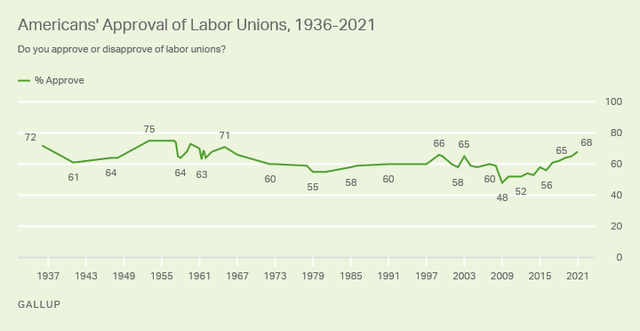

In fact, Gallup confirms this trend. Gallup polled Americans, “Do you approve or disapprove of labor unions?” and the results are quite staggering:

2021’s 68% level of support for labor unions (“approval of labor unions”) is the highest level since the 71% support reading in 1971. Just since 2009 (48%), during the Great Recession, support has increased by more than 40% to the most recent reading in September 2022 (68%) – this is a significant increase, especially when considering the time period (less than 14 years)… and we are starting to see its effects.

More Than A Freight Railroad Strike – The Significance

The 12 unions involved in negotiations with railways, representing approximately 115,000 members as of October 26, 2022, — who are primarily employees at freight railways — are seeking two key concessions: better pay and more flexible work schedules (with a focus on time off for medical appointments). They are serious. Unions made it clear that workers were prepared to walk off the job, threatening to essentially cripple the railroads and in turn (significant parts of) the U.S. economy. This threat was amplified because several essential railroad corridors are leased to and controlled by freight railroads facing potential walkouts. These employees are necessary for (any) trains to traverse these corridors, also often used by passenger railroads such as Amtrak.

In fact, “about 97% of its [Amtrak’s] 22,000-mile system runs along tracks owned by freight lines and are not under Amtrak’s control.” The effects of a freight railroad strike would extend far beyond just the shipping and freight industries, having ripple effects in essentially every sector of the US economy.

Nearly a third of U.S. freight moves by rail, second only to trucking. The Association of American Railroads estimated that a nationwide rail service interruption would have idled more than 7,000 trains daily and cost the [US] economy more than $2 billion a day.”

– “Railroad Unions and Companies Reach a Tentative Deal to Avoid a Strike” by Jim Tankersley (New York Times).

While there is an estimated greater than $2B/day financial cost that accompanies a (potential) national railroad strike, its likely impacts reach far beyond just economic effects (though this $2B/day cost has become a common figure when discussing the potential walkout). Tankersley argues that since the midterms were just about 8 weeks away at the time of the first planned walkout (early September 2022), President Joe Biden and Democratic leadership were heavily invested in avoiding a potential shutdown. Marty Walsh, the Secretary of Labor, brokered negotiations (read this a very interesting piece on it). When a “deal” was reached, President Biden prematurely announced it, using it as a political victory (like in the video linked above from September 15, 2022, in time for the midterm elections).

Some pointed to and applauded the deal, stating that it was a result of unions and railroads negotiating in good faith, and used it as proof that the current union system works. But not everyone agrees. The strikes (as well as the threats of strikes and walkouts) had a significant cost on railroad companies that had to limit or cease operations, and it appears that almost all stakeholders were relieved to see the dispute resolved. For instance,

“The Retail Industry Leaders Association said in a release that its members had ‘endured enormous supply chain challenges over the last few years… [and] we are relieved that rail carriers and labor unions were able to reach a tentative agreement to avoid any further disruption.'”

Others, including “[r]etailers and other business groups welcomed news of the deal, saying that, if ratified, it would avoid potentially devastating shipping delays for the holiday season.”

Essentially no one wanted to see a strike, but it was perhaps the only viable tool available to railroad workers to improve their working conditions and compensation. The deal prevented likely devastating walkouts, but this was more than just a victory for America’s economy. Tankersley continues in his article:

Congressional leaders — who were under increased pressure to step in to block a strike if the negotiations had not produced a deal by Friday — also lauded the agreement and, in particular, labor unions that represent a critical voting bloc. The agreement spared Democratic leaders in particular from what could have been a politically treacherous set of votes, pitting the party’s deep support for organized labor against its need for economic stability ahead of the midterm elections.”

This has been a peculiar and fascinating series of events, at a politically and economically pivotal moment in American history. While I could rehash the details surrounding the strike, what really matters is… what does this all mean? Well, for starters, without a resolution entire industries could be devastated. U.S. railroads play a pivotal role in the country’s supply chain, which has already revealed its weaknesses in recent months (and throughout the pandemic). Railroads — or more accurately, their employees — leveraged this fact to their advantage at the negotiating table. A September 14th article (linked above) by the Associated Press entitled “From carmakers to refiners, industries brace for rail strike” outlined the far-reaching effects of a potential railroad strike. These (negative) effects ranged from commuting and the auto (production) industry to energy, agriculture, and retail (in regards to both receiving inputs and shipping the end product).

While I highly recommend reading the article for yourself, I want to highlight one interesting point raised regarding the substitute of trucking (emphasis added):

Experts say retailers have been shipping goods earlier in the season in recent months as a way to protect themselves from potential disruptions. ‘But this buffer will only slightly minimize the impact from a railroad strike, which is brewing during the critical holiday shipping season,’ said Jess Dankert, vice president of supply chain at the Retail Industry Leaders Association… [Dankert] noted that retailers are already feeling the impact from the uncertainty as some freight carriers are limiting services…

[And] that retailers, noticing a slowdown in shipments, are now making contingency plans like turning to trucks to pick up some of the slack and making plans to use some of the excess inventory that it has in its distribution centers…

But [Dankert] noted that there are not enough trucks and drivers to meet their needs. That scarcity will only drive up costs and make inflation worse…

‘As we have seen in the past two and half years, if there is a breakdown anywhere along the supply chain, one link falters, you see that ripple effect pretty quickly and those effects just spread from there…'”

What may appear to be an industry-specific strike, among a limited number of companies, could potentially dismantle supply chains and in turn significant segments of the U.S. economy. At this point, negotiating with employees and bringing them back to work may not even be just an issue of managing costs, but rather one of protecting America and its economy at large.

Adding to Dankert’s comment that trucking is not an appropriate substitute: even if there were an ample supply of trucks and drivers when there is a choice, rail is by far the cheaper and more efficient shipping method. According to RSI Logistics: “The differential in cost between the two modes is $0.105 per ton-mile. Reducing truck transit and choosing the optimal rail transload facility will help to maximize cost savings…” In fact, the cost to ship a truckload and a railcar between Houston, TX, and Cleveland, OH is largely similar: the truckload is actually cheaper at $5,159 compared to $6676 for the railcar… However, one railcar is approximately equal in size to four truckloads, so when adjusting for size, we can see why shipping by rail is much more efficient.

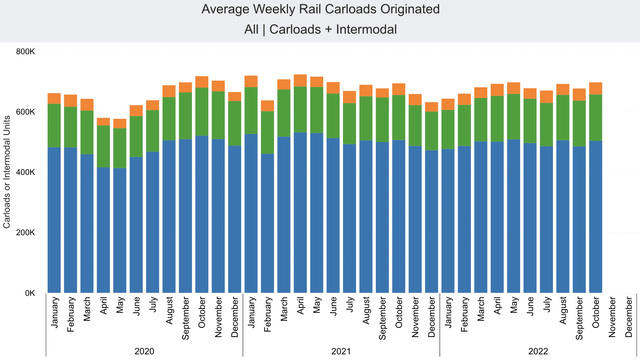

As we approach the holiday season, I would expect an uptick in the transportation of freight by every mode (or at least where there is the potential for an increase in volume) — but especially by rail. There is no adequate substitute… the closest replacement would be trucking. But even ignoring the far greater fuel expense, as previously noted there is already a large truck driver shortage in the U.S. that would have to be addressed. Railroad companies stand to benefit from increased freight from the holiday season -and it’s already beginning. The Association of American Railroads’ data suggests that this increase has started with an uptick in the Average Weekly Rail Carloads Originated (chart below) in October of 2022, similar to previous years.

*PLEASE NOTE in the chart below blue represents the United States, green represents Canada, and orange represents Mexico.

Average Weekly Rail Carloads Originated (US, Carloads + Intermodal) (Association of American Railroads)

While the Association of American Railroads’ data may suggest a somewhat stable origination of (freight) carloads since the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in January 2020, I think that it is essential to realize and understand that the St. Louis Fed is seeing a very different picture over a longer time horizon:

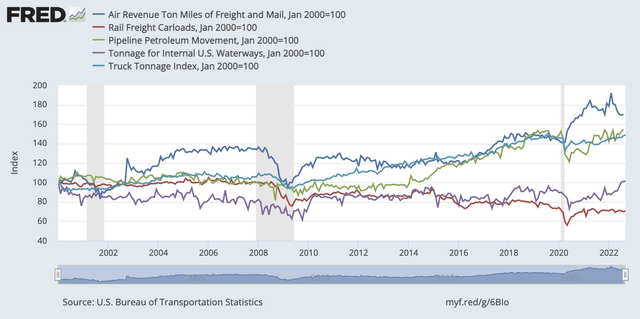

Indexed Freight Movement by Transportation Mode (FRED by the St. Louis Fed)

Focusing the chart above on just Rail Freight Carloads (indexed to 100 in the year 2000), we see that railroads seem to be performing the worst of any mode of freight transportation since January 2000 (the first year of this data).

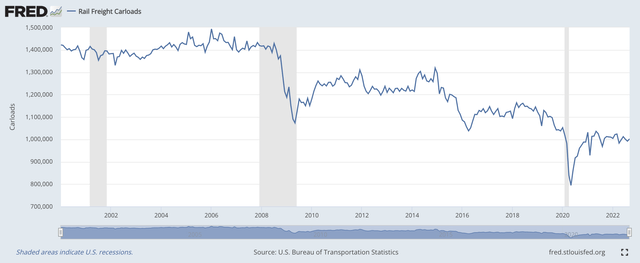

Indexed Freight Movement by Rail (FRED by the St. Louis Fed)

…and it really doesn’t look good. While the original FRED blog post was published in 2016, the St. Louis Fed has continued to update the data (up to as recently as September 2022), and the freight railroad situation seems to have only gotten even worse. In fact, it appears that every other mode of freight transportation except rail has improved (in the relative amount of freight transported) since the onset of the pandemic (2020). The St. Louis Fed noted in 2016 that (emphasis added):

The United States is large. Americans buy things often. So, all kinds of goods get hauled over great distances all the time. And, once again, FRED has some relevant data.

The graph tracks various modes of transportation for freight. And even though these indicators have different units (tons, short tons, ton-miles, and barrels), FRED’s graphing flexibility lets us compare them in a logical way. Once we change the units to an index, setting all values at 100 starting in the year 2000, we can compare the evolution of these indicators over time. It looks like freight hauled by rail is slowly but surely losing its market share, while freight hauled by trucks has fared better.“

The FED’s data illustrates how much freight transportation has changed in such a short period of time. While the 2016 blog post may have encompassed the larger trend since 2000, recent truck driver shortages as well as an increase in fuel prices have certainly influenced it. The estimated driver shortage (defined as “unfilled driver jobs”) according to the American Trucking Association (ATA) improved from 80,000 in 2021 to 78,000 this year; however, the gap is only expected to increase in the future with an aging workforce and increased demand for freight. There is no perfect substitute for trucks, but the closest would certainly be rail (or at least rail intermodal). While freight railroads are also potentially facing worker shortages due to the threat of a strike, this problem can be resolved without finding and training new workers. Instead, rail companies need to negotiate and agree on a new employment/union contract. Relations with disgruntled employees are one of the two major potential issues I see for railroads.

Other Considerations

There are many different factors at play. For instance, the fact that the FED’s data indicates that Air Revenue Ton Miles of Freight and Mail, Jan 2000=100 has experienced far greater (volume) growth than any other mode since the outset of the Pandemic in 2020 is extremely surprising to me. In fact, it didn’t make much sense to me at all, especially with the increase in the cost to ship such freight (due to higher jet fuel prices and labor). I would have thought that transporting freight by air(plane) was already the most expensive method of shipment, and thus would have experienced negative growth. But it’s just not that simple.

According to CNBC’s Leslie Josephs, the reality is that:

Air freight is a tiny part of the overall cargo market, but supply chain problems, travel restrictions and voracious consumer spending pushed the niche to the forefront during the pandemic…”

Consumers’ demands for goods — and for them to be delivered quickly — will likely never change. But, with companies like FedEx recently forecasting a global recession and cutting costs (as well as capacity), how these goods are delivered likely will. In fact, Ms. Josephs explains that air freight prices — and thus demand — are actually decreasing:

Now concerns about the economy, shifts in consumer pandemic spending habits — e-commerce binges this summer gave way instead to a stampede of vacation travel — and an increase in capacity are pushing air freight rates downward.

Even as air freight rates decline, they still remain in a completely different realm than that of other methods of freight transport because of the cost of jet fuel. That said, most items are not transported by aircraft due to the prohibitive cost, though aircraft do offer a unique expedited delivery schedule. The cheapest shipping option is almost always by sea (cargo ship), which makes sense given the increased fuel efficiency due to the scale of freight transported. But each individual method has its own benefits and detriments that must be weighed against the desires of those shipping goods. With that said, aircraft and cargo ships alone are almost never enough to get cargo to its end destination — that is why freight is often transported through an intermodal method (through multiple modes of shipment).

Trucks and trains have the highest freight volumes transported of any land-based mode. While there are still limitations — especially with trains — they can get goods (at least) close to where they need to be delivered. But with the changing economic landscape, it is becoming much cheaper and more advantageous to transport freight by rail.

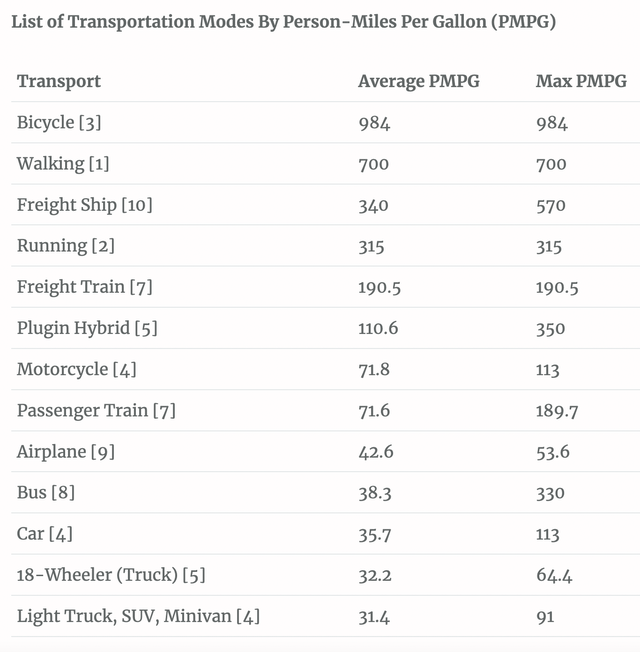

List of Transportation Modes By Person-Miles Per Gallon (PMPG) (True Cost Blog)

As we can see from the table above, freight trains are one of the most fuel-efficient methods of transportation in terms of average Person-Miles Per Gallon (behind only smaller-scale methods and freight ships). There are benefits and detriments to each method, and the optimal method of shipment is determined by specific circumstances – and often consists of a combination of methods (intermodal shipping). But for long distances over land, nothing beats the efficiency and volume of freight trains.

Because of their fuel efficiency, freight railroads have greater protection from the rise in fuel (diesel) costs, which will likely only boost railroad stocks if oil continues to increase. The primary issue that remains is getting their workers back on the job. But as we have seen, both sides have been willing to come to the table and negotiate. There are also other parties in play. If no agreement is achieved:

Congress may be forced to intervene, however reluctant lawmakers may be. They could impose either the agreements that the unions rejected or the recommendation that a presidentially appointed board of arbitrators made over the summer — or they could just send the parties back to the table by extending the cooling off-period.”

– President of largest rail union predicts congressional intervention after ‘no’ vote (Politico, November 22, 2022)

Likely Resolution

There is too much at stake for the American economy and politicians themselves for there to be no intervention, especially since this coming strike is (purposefully) planned near the holiday season. There have been several positive signs that both sides are willing to negotiate; but, if worse comes to worst, it has been made clear that Congress will intervene in order to avoid a railroad shutdown (I, II, III).

Less than one week after the President of SMART-Transportation Division (“the country’s largest rail union”) predicted congressional intervention:

Speaker Nancy Pelosi said on Monday [November 28th] that lawmakers plan to intervene this week in the deepening labor dispute between rail companies and their unionized workers, voting on whether to impose an agreement that could avert a shutdown of the nation’s freight trains just before Christmas.”

– Congress Looks to Intervene in Rail Dispute as Strike Deadline Looms (New York Times, November 28, 2022)

This came “shortly after President Biden called on Congress to act, saying the dispute cannot be allowed to ‘hurl this nation into a devastating rail freight shutdown.'” With the December 9th strike deadline nearing, the need for action is becoming apparent.

In a statement, Mr. Biden urged the House and Senate to swiftly pass legislation to impose a compromise labor agreement that his administration helped broker but that has failed to win the support of all the rail labor unions.”

– Congress Looks to Intervene in Rail Dispute as Strike Deadline Looms (New York Times, November 28, 2022)

Speaker Pelosi has stated that “this week, the House will take up a bill adopting the tentative agreement — with no poison pills or changes to the negotiated terms — and send it to the Senate.” With Democrats no longer holding a majority of seats in the Senate, it is less clear what will happen. What is clear, however, is that an agreement needs to be made before a December 9th deadline when several unions are planning to strike.

There is an extremely fine line that Biden and his administration need to walk between satisfying union members and protecting the economy. Both President Biden and Speaker Pelosi have supported the unions while simultaneously attacking railroads, “[b]ut Mr. Biden’s call for Congress to act underscores the recognition that a rail strike could have a devastating effect on the fragile economic recovery after the Covid-19 pandemic.” A strike would further cripple supply chains, driving up prices (and thus inflation).

Despite being “a staunch union backer,” President Biden seems to understand the stakes at hand:

‘Let me be clear: A rail shutdown would devastate our economy,’ the president said. ‘Without freight rail, many U.S. industries would shut down. My economic advisers report that as many as 765,000 Americans — many union workers themselves — could be put out of work in the first two weeks alone. Communities could lose access to chemicals necessary to ensure clean drinking water. Farms and ranches across the country could be unable to feed their livestock.’”

– Congress Looks to Intervene in Rail Dispute as Strike Deadline Looms (New York Times, November 28, 2022)

Interestingly, President Biden “has previously argued against congressional intervention in railway labor disputes, arguing that it unfairly interferes with union bargaining efforts.” In fact, “[i]n 1992, he was one of only six senators to vote against legislation that ended another bitter strike by rail workers.” Biden’s changing stance indicates the significance of a resolution. Additionally, the fact that “[t]he railroad industry immediately threw its support behind Mr. Biden’s call for legislation” indicates that a resolution is not only what’s best for the country, but also for railroad companies.

President Biden, a staunch union supporter, stated that:

‘I am reluctant to override the ratification procedures and the views of those who voted against the agreement… But in this case — where the economic impact of a shutdown would hurt millions of other working people and families — I believe Congress must use its powers to adopt this deal.’

– Congress Looks to Intervene in Rail Dispute as Strike Deadline Looms (New York Times, November 28, 2022)

While there is much to be said about the necessity for workers’ rights and living wages, it appears as though railroads will be the real winner. Congress will likely mandate “the tentative agreement that the Biden administration helped broker in September.” This is despite “[f]our of the 12 unions representing more than 100,000 employees at large freight rail carriers [voting] down the tentative agreement…” While the agreement does provide an almost 25% raise between 2020 and 2024, it threatens to disgruntle many employees “who argue that it does not go far enough to resolve what they say are punishing schedules that upend their personal lives and their health.”

While “many members are likely to be upset by the prospect of congressional intervention,” it is in their favor that it occurs now rather than in 2023 “when the House comes under Republican control and may be more likely to back the skimpier deal.” While it seems every party will benefit from a deal, railroads stand to gain the most.

How to Play the Stoppage

I believe that even if workers wanted to strike, it would not last long, especially given its timing so close to the holiday season. With railroad employees likely returning to work, and operations back to normal in time for the peak season, the railroad companies themselves are likely to be the primary beneficiaries. They have demonstrated their essential function to the U.S. economy. There already is no true substitute, and with the possible alternative methods facing greater increased costs from the rising price of oil, the need for rail is greater than ever. It seems very likely that freight railroad companies will come out on top and play an even larger role in transporting freight in the future (at least while oil prices remain elevated).

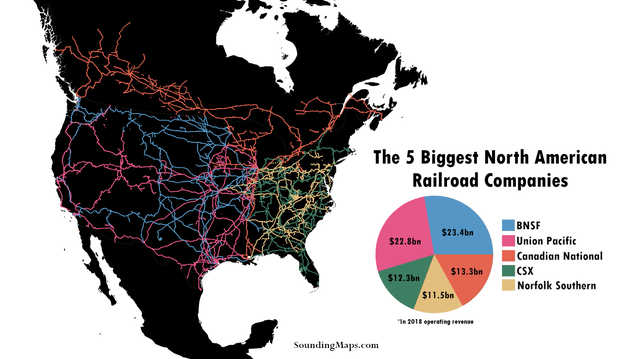

There are many railroad and ancillary companies that one can invest in, but one group of railroads stands out. There are seven Class I railroads, which, according to Sounding Maps (a website where contributors map data), are the:

…major railroads [that] dominate the US and Canadian railroad industry… Most of which formed as a result of a wave of consolidation in the 1980s and 1990s.

All said and done, the ‘Class I’ railroad track miles totals about 92,000. The track managed and owned by these companies are crucial to moving goods to and from our ports for importing and exporting goods.”

In addition, the author claims that these seven railroads are the largest and most profitable in North America. The US rail network, however:

“is dominated by 5 railroad companies… [and t]he top railroads dominate the rail market with a market cap in the tens of billions. “These five railroads are BNSF (BRK.A), Union Pacific (UNP), Canadian National (CNI), CSX Corporation (CSX), and Norfolk Southern (NSC).”

The additional two Class I railroads are Canadian Pacific Railway (CP) and Kansas City Southern (acquired by Canadian Pacific Railway in 2021) but “[w]hen combined, they generated less than $10 billion in revenue.”

Focusing on the five previously listed railroads, each operates in its own general region, but there is certainly overlap:

The 5 Biggest North American (Freight) Railroad Companies (Sounding Maps)

The figure above clearly illustrates the reach of these Class I railroads. With that said, there has been a downward trend in revenues since 2018 (the seven Class I railroads saw $80.4B in operating revenue in 2021 compared to $93.3B in 2018). This 13.8% decline in revenues is significant, but it has not impacted each company and their respective stocks uniformly.

Comparative Stock Analysis

YTD Selected Class I Railroad Stock Performance (Yahoo! Finance)

Among the aforementioned railroads, Canadian National’s stock is the only railway company to achieve positive returns year-to-date and has achieved the greatest returns since the onset of the pandemic (Berkshire Hathaway, the owner of BNSF, has performed similarly, but is not a railroad company and is much more diversified). CNI owns as much of the rail network as CSX and has more revenues than Norfolk Southern.

While CNI appears to be the most attractive play, in my opinion, any of these companies’ stocks will likely perform well with a resolution — which is appearing more and more likely as Christmas draws closer. The Class I railroads have the combination of fuel efficiency and reach necessary to outperform their freight competitors in this high-priced oil environment, and I believe that their stocks will follow suit.

Be the first to comment