dml5050/iStock via Getty Images

Introduction

Post Dodd-Frank, there were two important changes in the financial climate. On one hand, financial regulators moved aggressively to limit risk-taking by systemically important financial institutions – large commercial banks, major exchanges, clearers, and rating agencies.

On the other hand, financial risk itself declined dramatically in a market overflowing with Fed-provided liquidity. Until now.

The 15-year vacation from normal market risk has predictably led to a financial market with much-reduced risk management capabilities. Worse, the lower perceived cost of risk-taking has seduced market participants into taking risks they would never have assumed under normal risk conditions.

Unfortunately, the financial markets are about to awake from the easy-money-induced coma of the past 15 years. Here are a few obvious steps market participants could take now to improve the market’s capacity to absorb the coming risk.

Effect of Post-Dodd-Frank regulation

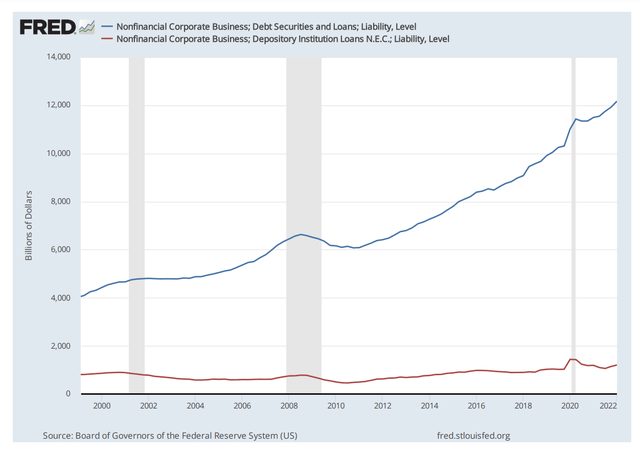

Figure 1 (FRED/Author)

Debt markets. Regulatory initiatives following Dodd-Frank have made the banks safer. Safer but far less relevant for financial risk management. The burden has been shifted from banks to financial markets, as shown in Figure 1.

This shift away from banks’ risk management services presents financial market regulators with a historically common situation. The regulators’ squelching of the commercial banks’ risk-taking has led to declining bank importance to their customers and a movement from banking to Prime Money Market Funds (PrimeMMFs), the change in institutional investment direction is illustrated in Figure 2 below.

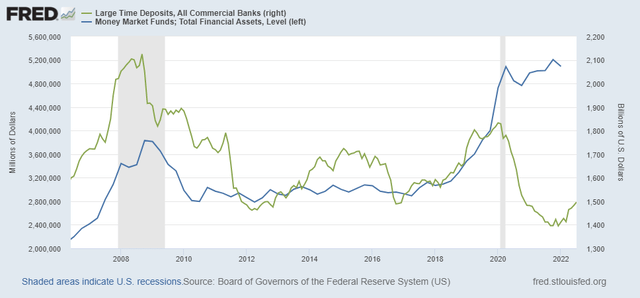

Figure 2 (FRED/Author)

The shift in the locus of risk has inspired a regulatory drive to capture the risk that got away. Twice – during the Financial Crisis and during the COVID crisis – the Fed has moved to bail out the PrimeMMFs. (Read here).

Regulatory empire-building makes risk management more expensive and less effective.

Stock markets. Like banks, the inefficient exchanges have been deserted by their customers. Since 2008, the failings of the SEC’s National Market System (NMS) have continued to embarrass regulators and legislators. The excessive cost and inefficiency of stock markets have continued to balloon. At last count, there were an absurd 15 SEC-registered exchanges where one is enough. The stock exchanges have become so inefficient that retail brokers have deserted them. Roughly 80% of retail orders are executed OTC by wholesalers.

Pluses and Minuses of the declining importance of banks

Pluses. This shift from banks to markets has the important advantage of dramatically reducing the resource cost of financial risk management. Market-traded hedges like financial futures and options require less balance sheet capital to reduce corporate financial risk.

Minuses. The offsetting negative to the lower cost of capital of market-provided risk management is a greater unmet corporate demand for risk-reducing services since leaving the banks creates an unmet need for non-bank risk reduction from a market source.

Now risk management answers can only come in two forms.

- Micro-risk management provided OTC by wholesalers.

- Macro-risk management provided by less-risky financial instruments and markets.

Present risk management capacity

Riskier balance sheets. The regs stifling bank risk-taking moved the locus of risk management away from the banks, reducing their importance in financing and financial risk management. New balance sheets now carry the risk. Notably, PrimeMMFs are particularly vulnerable to changes in the volatility of credit conditions, forcing the Fed to rescue them twice since the Financial Crisis of 2007-2008, despite the relative quiescence of interest rates during the post-Crisis period.

The message is clear. When bank risk-taking is stifled, the risk to financial markets doesn’t decrease. Instead, the risk moves to non-banks that have far less ability to manage and bear the risk. So total risk management capacity falls as the risk moves from capable to less capable hands.

Riskier equity markets. A new class of market risk managers; wholesalers (Citadel, Virtu, others), and investment houses (BlackRock, Vanguard, others) unfettered by reactionary bank regs, has taken over risk management in stock markets from the banks.

These new players are relatively innocent of the politics of finance. During the January 2021 meme stock fiasco, failures of the stock market (read here) caught the attention of financial regulators and legislators. Payment for Order Flow (PFOF) became a center of attention at the SEC.

PFOF – payments by wholesalers to retail brokers for the right to execute batches of orders – is a retail investor abuse, but relatively less abusive to much-abused retail investors, when compared to maker-taker fees exchanges charge to fill retail orders. This new abuse within the Pandora’s-box-like panoply of older retail investor abuses only demonstrates the near-criminal inefficiency of the retail portion of securities markets. PFOF succeeds only because wholesalers have chosen to take a half pound of flesh from retail investors, less than the full pound taken by the exchanges.

The optics of PFOF are terrible. PFOF appears to be payola. In this view of PFOF, wholesalers bribe retail broker-dealers like Fidelity and Robinhood to send retail orders their way. Then wholesalers get fat filling the orders at a discount to the “real” inside market.

But if PFOF is such an expensive way to fill retail orders, why don’t these orders flow naturally to the exchanges?

The coming return to normal risk conditions

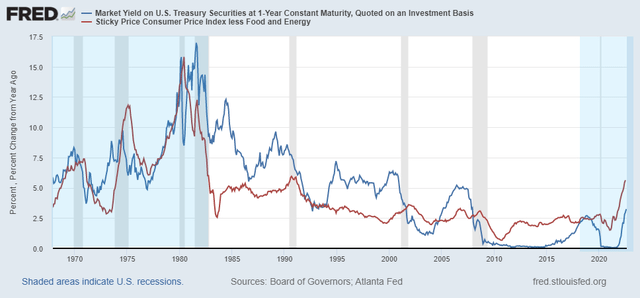

Debt markets. A look at the relationship between inflation and interest rates in Figure 3 below shows why there is reason to believe that we are beginning a cycle in financial markets like the expansionary volatile financial-risk-intensive stage of the business cycle between 1972 and 1982.

Figure 3 (FRED/Author)

In Figure 3, compare the two areas in blue. Both inflation and interest rates are volatile and rise only in those two periods. This contrasts with the period from 1984 to 2008 when interest rates usually exceeded the inflation rate, slowly wringing inflation from the financial system.

The decade it took to return to low inflation had a cost, excess investment when investment costs fell to minuscule levels, resulting in the Financial Crisis of 2007-2008. This financial market crash inspired the Fed to sound the call to battle stations, resulting in a decade of near-zero real costs of capital. But now we have returned to another period of high and volatile interest rates and inflation.

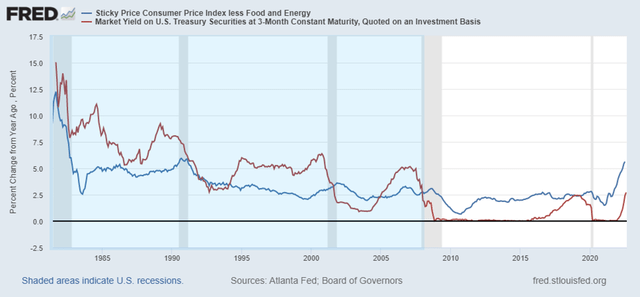

The reason for this return to normal high volatility is displayed in Figure 4, which compares core inflation to the more policy-driven 3-month Treasury.

Figure 4 (FRED/Author)

Note the clear switch in 2008 to inflation rates exceeding policy-driven interest rates. Would a rules-based policy like “Set the policy rate to the core inflation rate.” have been better? With 20-20 hindsight the answer seems to be yes. Score one for the Classical School.

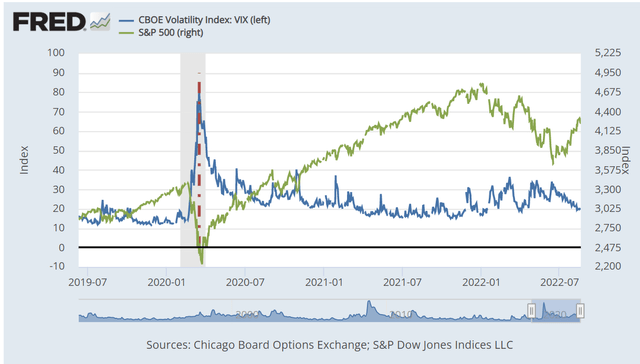

Stock markets. The stock market is also warning of a financial crisis. Note the permanent upward shift in average market volatility following the COVID-created recession in Figure 5.

Figure 5 (FRED/Author)

Financial markets are unprepared

The shift from commercial bank risk management to market sources has come during 15 years of extremely easy money. The one recession that occurred during the period was driven by COVID not the economy directly.

But seasoned financial market participants understand a simple verity. Market-wide risk is not a function of financial regulation. It depends instead on the uncontrollable gusting bluster of the economic wind. Thus, as the risks of regulated entities are damped by regulation, risk only moves to unregulated firms and markets.

There is little doubt that financial markets show the effects of the prolonged period of easy money and low risk now coming to an end.

How do our debt and equity markets stack up?

Here are four measures of market health.

- Simplicity. A simple structure eases the identification of trading costs and performance measurement.

- Transparency. A transparent structure enables retail traders to compare the efficiency of vendor performance to alternatives.

- Homogeneity. A market focused on a few dominant representative investments provides traders with a summary measure of the forces at work throughout the market.

- Stability. A market should not be vulnerable to collapse under the weight of higher-than-normal volume or a sudden increase in price volatility.

Debt markets. The primary index of credit risk in the short-term debt market, LIBOR, is being retired by regulators without a suitable replacement. Current candidates to replace LIBOR in its primary function of credit risk forecasting are ad hoc instruments like Bloomberg’s BSBY, Invesco/SOFR Academy’s AXI, and CME Group’s Term SOFR. All have the fatal flaw that they are not a market price of any instrument at the close of trading.

There is no index to replace LIBOR now because there is no debt instrument that comes close to meeting the four market standards. It will take either a happy accident like the one that created LIBOR or a determined concerted effort on behalf of private sector debt market participants to create a market and instrument that provides the credit risk information once supplied by LIBOR.

Equity markets. The activist SEC chair, Gary Gensler, has promised to fix the broken NMS. The SEC proposal to have wholesalers somehow bid in an organized market for retail order flow plainly increases the complexity of the too-complex NMS. Regulators’ hands are always tied. They can regulate the existing technology, but they cannot innovate themselves. Thus, regulation-induced changes inevitably complicate markets.

Nonetheless, it is hard to see how the SEC proposal does anything to reduce the resource cost of retail investment.

Proposed solution

There is an obvious improvement that would increase the efficiency of both debt and equity markets. Create a new exchange with the properties below.

- Ability to originate securities and warehouse the NMS securities used to back them.

- Investor ownership of the exchange like Vanguard.

- A captive broker-dealer that offers PFOF to retail brokers, then pays retail users the PFOF.

I have explained the first two improvements elsewhere. The third is the subject of a coming article.

Conclusion

Bank regulation and monetary policy since the Financial Crisis have created a reduction in the banks’ capacity to manage financial market risks. Further, market-wide risk has not been reduced but instead migrated to the portfolios of investment houses and PrimeMMFs that are less skillful risk managers than the banks.

15 years of policy-driven easy money has produced an overheated economy and financial risk-taking that makes sense only in a zero-interest rate environment.

SEC regulation has done nothing to reduce the steady exodus of retail transactions from exchanges. In short, stock markets are out of control, just like debt markets, and neither regulator has the capacity to help.

The recent history of interest rates compared to inflation and of stock prices compared to stock market volatility suggests that the economic policies of the past 15 years, like the economic policies of the mid- ‘60s and ‘70s, have been so expansionary that they may create the unfortunate outcome of stagflation (simultaneous high inflation and recession.)

Our financial markets are ill-prepared for this outcome.

Be the first to comment