NAPA74

Investment thesis

Ecopetrol S.A. (NYSE:EC) is Colombia’s national oil company (or NOC) and also the largest company in the country. The government owns 88.49% of the stock. The 11% float is traded in Colombia and on the NYSE via ADR listing.

The investment story is simple and is a trade-off between two factors:

- On the positive side, Ecopetrol is currently one of the most discounted oil producers, and its large dividend stands out relative to other NOCs too.

- The negative is the geopolitical risk associated with Colombia’s new, leftist president. The concern is that the government may push the company into unprofitable initiatives to fulfill social objectives, or may otherwise take actions against the interest of minority shareholders.

As the valuation side is fairly obvious, the article focuses mostly on the geopolitical aspect. My thesis is that the political risk priced into the stock is exaggerated for three reasons:

- President Petro has a minority in Colombia’s congress, so policy changes are only possible via broad coalition building. However, the broader the coalition, the smaller the changes from the status quo can be.

- To fulfill the social aspects of his agenda, Mr. Petro will need significant government revenue to finance the spend. So rather than killing the proverbial “golden goose” (that is, Colombia’s hydrocarbons sector) through aggressive environmental reforms, a more logical choice would be to avoid disrupting the income potential of Ecopetrol and rather go for symbolic “quick wins” on the environmental front.

- At a macro level, Colombia’s sovereign credit default swaps (or CDS) and the spreads on Ecopetrol’s own USD listed debt suggest that geopolitical risk perceptions may have peaked in October.

If the presumably more sophisticated bond market is correct, the equity market should follow and re-rate Ecopetrol’s shares higher. In the meantime, investors can benefit from the massive dividend.

Company background

Ecopetrol is Colombia’s NOC. Its separation from the government began in 2003, when the company ceded its administrative role as hydrocarbons regulator to the National Hydrocarbons Agency. The initial public offering was in 2007, when Ecopetrol’s common shares were listed on the Colombian Stock Exchange. The American Depositary Shares were listed on the NYSE in 2008.

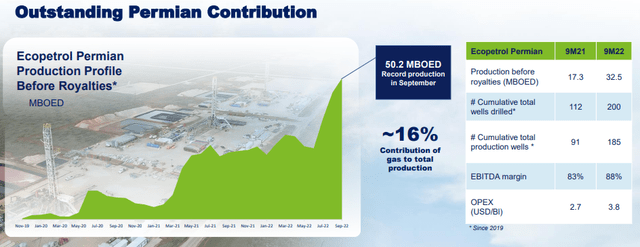

In recent years, Ecopetrol has expanded beyond Colombia. In 2017, the company entered into Mexico, where it received interest in two offshore blocks. In 2018, Ecopetrol entered the Brazilian pre-salt oil region, in partnership with other NOCs and majors. In 2019, Ecopetrol also started operations in the Permian through an alliance with Occidental Petroleum (OXY). In 2021, the company bolstered its marketing presence in Asia through a new trading entity in Singapore.

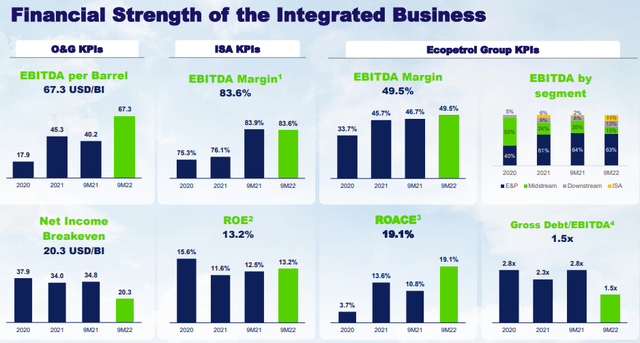

As a snapshot, EC produces about 700,000 boe/d and its refining capacity can absorb half of that. The company also owns significant electric transmission infrastructure. The transmission business may have possibly been “pushed” onto the company by the government, but nonetheless it seems to generate good ROE:

The Permian operation is becoming more prominent, and Ecopetrol is also expanding its marketing presence in Texas:

In my view, the fact that Ecopetrol now has material U.S. assets, which can theoretically be targeted in lawsuits, could also act as an important guarantee for Ecopetrol’s minority shareholders.

Valuation considerations

At 2.2x forward earnings and a 15+% dividend yield, Ecopetrol looks quite attractive from a valuation perspective:

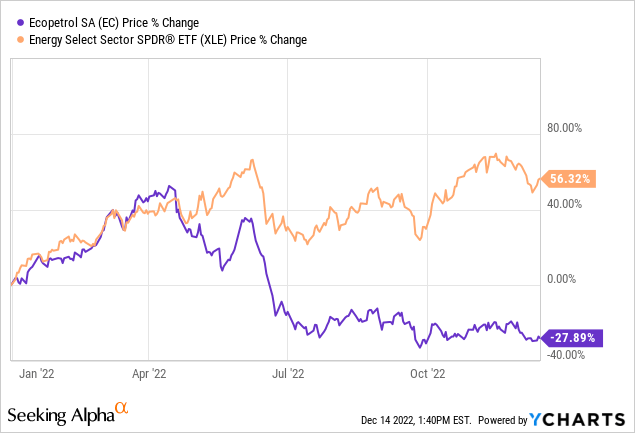

Ecopetrol is also one of the few energy stocks out there that is down year-to-date. A comparison to the S&P 500 energy sector (XLE) is enough to show this has almost everything to do with the presidential election and not much with oil prices:

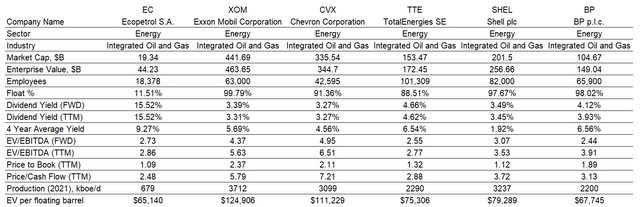

Compared to the Majors, Ecopetrol trades at quite a discount:

Seeking Alpha; Company SEC Filings; Author’s Calculations

The discount is larger relative to the two U.S. Majors, ExxonMobil (XOM) and Chevron (CVX); the European ones, Total (TTE), Shell (SHEL) and BP (BP) have a smaller premium over EC, perhaps because with the recent windfall taxes, Europe is also perceived as politically risky for energy companies.

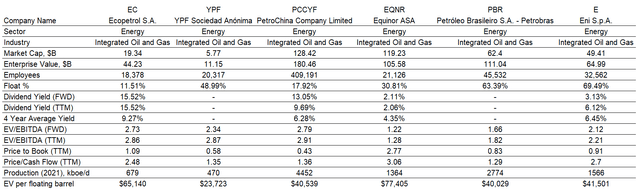

Infamously though, NOCs trade at lower multiples. When the government is a majority shareholder, there is always a risk that national priorities may come into conflict with the interests of minority shareholders. Ecopetrol’s valuation is in line with the metrics of other NOCs:

Seeking Alpha; Company SEC Filings; Author’s Calculations

The NOC panel includes companies from other countries undergoing political turmoil such as Petrobras (PBR). The situation in Argentina (YPF) is also not very good. Nonetheless, Ecopetrol’s dividend still stands out.

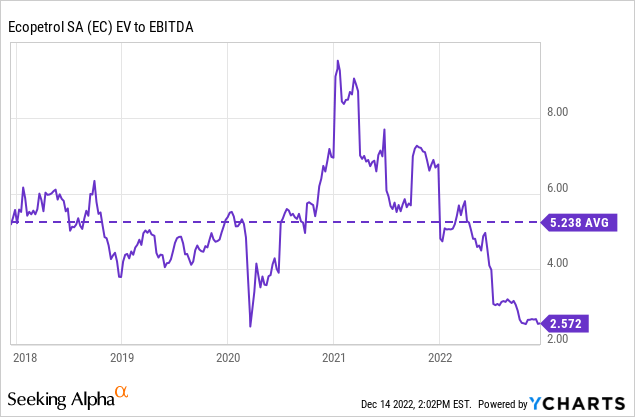

Compared to how the market valued it in the recent past, Ecopetrol also looks discounted:

Trailing EBITDA multiples have been in the 4x to 6x range. The higher ratios in 2021 were driven by the unusually low 2020 results. However, the 2.5x ratio in place now is unusually low; it only briefly touched that point before in March 2020 during the peak COVID lockdowns and OPEC+ price war.

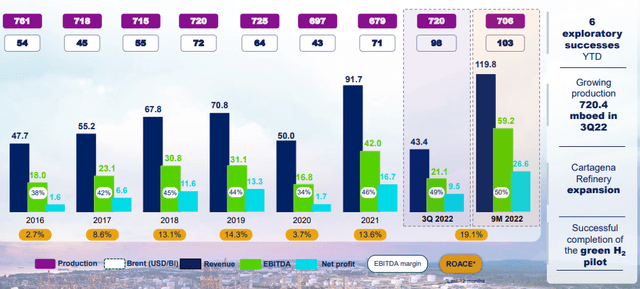

Meanwhile, the company is reporting record profits:

Nine-month EBITDA YTD equals the prior two fiscal years combined.

As a high-level target, I think the stock price could eventually return to the March-April levels, implying a 50% to 100% upside from here. Such repricing would also bring the valuation metrics more in line with their historical norms. However, that will not happen before the market gets comfortable with the political situation.

Reassessing the geopolitical risk

A common narrative in the media has been that Petro, a former guerrilla and Colombia’s first leftist president, would be very negative for the country’s oil sector:

To quote from the article:

Despite the fact that crude is Colombia’s number one export, Petro vows to be hostile toward the oil and gas industry and has pledged to stop awarding new exploration contracts. He allegedly wants to turn Ecopetrol, the country’s primary petroleum producer and biggest company of any kind by revenue, into a wind and solar provider. As Bloomberg reports, the Colombian government, owns 85% of Ecopetrol, so there’s little to stop Petro from accomplishing this.

The selloff in the Colombian peso, CDS spreads and equities with exposure to Colombia are all consistent with the narrative. I have also personally heard a couple of stories about expats moving their funds out of the country.

However, in my view these narratives are a bad take. They seek the journalistic sensationalism and ignore the reality that what a politician (Petro) wants isn’t always what they get.

Winning elections isn’t governing

To be clear, the point isn’t that Petro wouldn’t want to implement the agenda he has campaigned on. I don’t know what he really wants, but I am happy to assume that his platform reflects his goals. The point is, however, that once elected politicians step into office, their incentives change. Voters judge incumbents less so on their platform and more so through the prism of the voters’ own economic well-being. If you can’t pay your bills or afford groceries, you blame the guy in charge. This puts some pressure on politicians to drop less prudent aspects of their platforms once voters perceive them as being in charge.

In fact, a political science study, suggestively entitled “Neoliberalism by Surprise in Latin America,” found systematic evidence that left-leaning Latin American politicians tend to move to the right on policy during their term. The study concludes that, ultimately, neoliberal (unpopular) policies work best for constituents and that is precisely why elected officials have the incentives to pursue such policies. One better known example is perhaps the Peruvian presidential election in 1990, which was won by populist Alberto Fujimori against the conservative Mario Vargas Llosa. Once in office, Fujimori pivoted to the right and “stole” much of Vargas Llosa’ platform, effectively implementing neoliberal reforms. The bottom line is that, looking across the region, the arrival of a leftist leader in office doesn’t automatically imply a Venezuela scenario. In fact, what went on in Venezuela seems to be much more of an exception than the rule.

Political institutions matter too

Policy making doesn’t happen in a vacuum either. Colombia’s “Congreso”, has two chambers, not unlike the House and Senate in the U.S. Neither of these bodies are controlled by Petro’s party, which in turn means that the legislative process can only move forward with a broad winning coalition behind it. In other words, the system has a number of “veto players”, who due to the distribution of political power and policy preferences, can block changes from the status quo. Petro needs to avoid any veto players blocking him, but that will naturally drive policy towards the center.

This is exactly what seems to have happened with Colombia’s tax reform, which underwent a few months of negotiations:

On 6 October 2022, the economic commissions of Colombia’s Senate and the House of Representatives approved the tax reform bill. Now the modified bill will be discussed in second debate by the plenary of both houses before it can become law.

The tax reform approved in first debate includes several changes, agreed between the Government and a group of congressmen, based on the preliminary comments to the tax reform bill submitted by the Colombian Government on 8 August 2022.

Petro is not Chavez and doesn’t automatically get what he wants. On the contrary, his position is probably more similar to that of Joe Biden, who has to negotiate his agenda with Congress.

So what is politically possible?

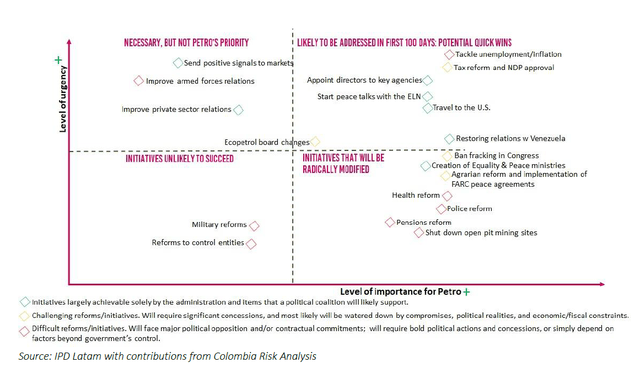

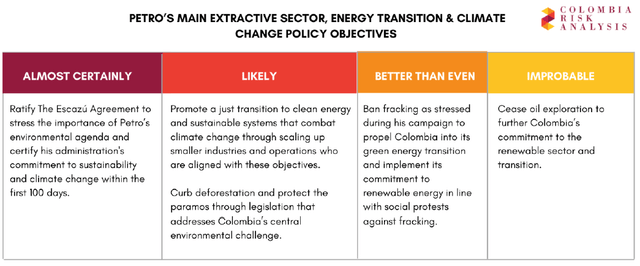

A report from Colombia Risk Analysis, a geopolitical risk consultancy focused on the country, attempted to rank Petro’s proposals by priority (for Petro) and the likelihood they would be accepted:

While Colombia Risk Analysis classified tax reform (which already passed as noted) as a “quick win,” Petro’s more radical proposals related to the oil and gas industry are deemed unlikely to pass without radical modification. Quoting from Colombia Risk Analysis (my emphasis):

Petro’s policies regarding the extractive sector are some of his most contentious proposals. His vision for ceasing oil exploration and banning fracking addresses his objective to assuage climate change and promotes more sustainable energy sources; however, it is not realistic. Considering the many burdens his administration will confront within the first weeks of the 100 days, Petro will be unlikely to tackle a sector that provides significant funding, meaning he will likely backtrack on his campaign rhetoric to avoid economic fallout. The rapid energy transition he had proposed earlier is likely to cutoff necessary funding for his numerous social programs.

Colombia Risk Analysis brings up a very good point; namely, that the government’s “purse” will also act as constraint. If Petro were to rush and kill the “golden goose” that oil and gas is for Colombia’s economy, as well as scare off foreign investment in the process, his budgetary receipts will fall critically and thwart the social aspects of his agenda (which, naturally involves spending more money):

The war in Ukraine has pushed the price of a barrel past 100 USD, which has created a massive windfall for Ecopetrol, taxes, and royalties, even with oil prices currently decreasing. Petro must be particularly savvy in determining his budget and fiscal framework when factoring in oil production, prices, the pace of the energy transition, and regulation of oil exploration permits. Without these cautions, Petro will be unable to deliver on his varied social programs and campaign promises due to a lack of government funds.

For Petro, then, the optimal play may be to avoid radical energy reforms and go instead for more symbolic environmental policy wins, in order to preserve the revenue generating power of the energy sector and channel it into the social reforms, which ultimately will determine his popularity. Therefore, despite the rhetoric, ceasing oil exploration may be politically impossible:

Colombia Risk Analysis also cautions on drawing parallels with Chavez:

Although his opposition loves to compare Petro to Chavez, Chavez did have overwhelming support unlike Petro, making their political realities vastly different. Chavez also had hard support from the military and PDVSA, which controlled the Venezuelan economy. Petro will not have the same authority and handle over the economy with Ecopetrol. Although Petro’s base wants to see heads on a spike, and quickly, Petro will have to straddle both ideological camps to advance any legislative changes.

Petro’s appointment as finance minister of José Antonio Ocampo, a centrist economist who didn’t campaign for Petro during the election, is also seen as indication that Petro won’t try to “rock the boat” on economic and energy policy too much. From Colombia Risk Analysis again:

Petro’s appointment of José Antonio Ocampo as Minister of Finance signals a shift in Gustavo Petro’s economic vision that suggests a greater allowance and reliance on the extractive sector and free trade. They hope to avoid affecting the investment climate and macro-financial stability, especially considering Petro’s strained relationship with the private sector and trade associations.

In summary, Petro, constrained by Colombia’s budget and legal framework, will have a rather narrow path ahead:

With Petro’s proposed policy to cease oil exploration, Colombia is likely to exhaust its current reserves in six to seven years, meaning the country will likely experience a doubling in gas prices with heavy implications for a country with such a significant poverty rate. To lighten this impact and the government’s dependence on extractives, Petro is likely to encourage other sectors to increase productivity. However, this will be anything but a smooth transition as most legal mines–including the fracking pilots and open-pit mining–have solid legal cases to back their operations, which is most likely to result in a plethora of complex, lengthy legal battles for Petro. To avoid being bogged down in his first 100 days in the extractive sector, Petro is likely to target more straight-forward aspects of the sector, such as illegal mining, where he can cooperate with the private sector. Petro will likely pass a mining and carbon tax, which will increment costs for those dependent on carbon to accelerate a phasing out of the energy source.

Some government statements already suggest Petro may have settled on protecting the “purse” first; according to recent reporting:

Colombia is targeting a 15% increase in crude oil output by using “enhanced recovery” technologies to take advantage of higher energy prices, even as it pushes to decarbonization, Minister for Mines and Energy Irene Velez said.

Speculating about political incentives is inherently subjective, but my personal feeling is that the camp which equates Colombia to Venezuela is exaggerating quite a bit.

The tax reform

The tax reform, which was ultimately approved (after modifications) on November 17, did indeed increase taxes on the extractive industries:

Companies receiving income derived from the development of certain extraction activities of non-renewable resources should be subject to a permanent CIT surtax which will vary between 0% to 15% for oil companies (total CIT rate between 35% to 50%) and between 0% to 10% for coal mining companies (total CIT rate between 35% to 45%). The applicable surtax rate would be determined based on a calculation that considers the average mining/oil prices within the 10 years prior to the year in which the surtax is determined and the average price of the product in the year in which the calculation is made…

Income derived from the sale of natural gas will be not subject to the CIT surtax…

Royalties paid for the exploitation of non-renewable resources will be not deductible for income tax purposes…

The tax reform repeals the five years accelerated amortization for investments in exploratory activities carried out between 2017 and 2027 as well as the incentive credit for oil, gas and mining investments.

Extractive industries are always taxed at high rates, so I personally don’t find 50% CIT rate to be excessive, even with non-deductible royalties; we have examples of higher windfall tax rates from Europe. I also don’t see Ecopetrol as the primary target of these reforms, but rather non-government owned entities. The government owns 88% of Ecopetrol, so even with 0% tax rate, it would still be collecting the vast majority of Ecopetrol’s distributions.

So is this really about the 12% minority interest? I highly doubt it. The minority piece is quite small from Colombia’s perspective, so it is probably not worth the trouble. Ecopetrol, as pointed out, is also rapidly expanding outside of Colombia and in the Permian in particular. The company has plenty of U.S. based assets that could probably be targeted by legal action if Colombia disregards Ecopetrol’s corporate bylaws protecting the minority stake.

Lastly, it is even possible that the tax reform contributes to Colombia’s overall fiscal stability:

The reform appears fiscally responsible. It raises revenue to reduce the deficit, which rose to almost 8% of GDP in 2020 on the back of pandemic spending. This year, deficit will fall to 5.6% of GDP and should continue to decline. If the fiscal rule mandated by law is respected, the deficit will fall to 4.6% in 2023.

For Ecopetrol’s minority shareholders, more tax means less dividend, but, in the longer term, a more fiscally stable Colombia will be a positive factor.

The macro view

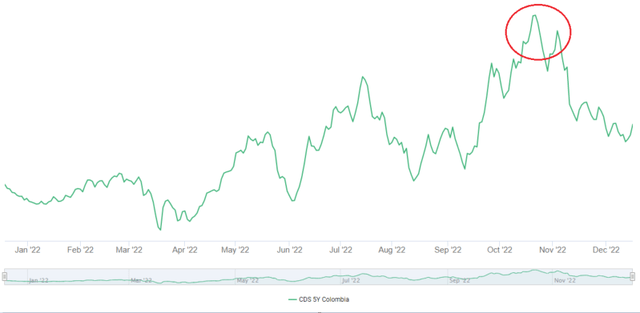

The bond market is frequently said to be a more sophisticated weighing machine of macro risks. So let’s look first at Colombia’s 5-year credit default swap rates:

The CDS rate in late October was about 400 bps, but has come down to 265 bps since then. It suggests that, for now, the bond market’s risk perceptions may have peaked.

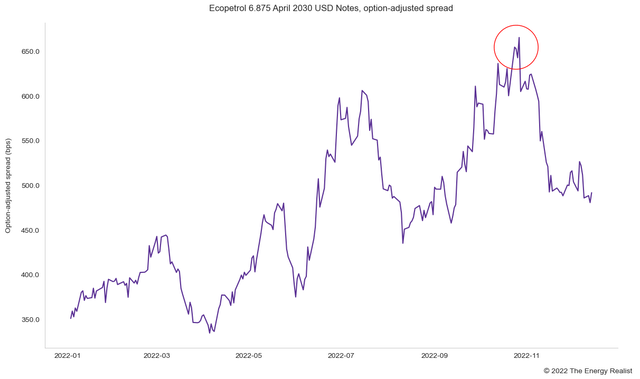

Ecopetrol itself also has several bond issues registered with the NYSE. I looked at the 6.875% USD-denominated notes due in April 2030. The option-adjusted spread also suggests that October may have marked the peak risk perceptions:

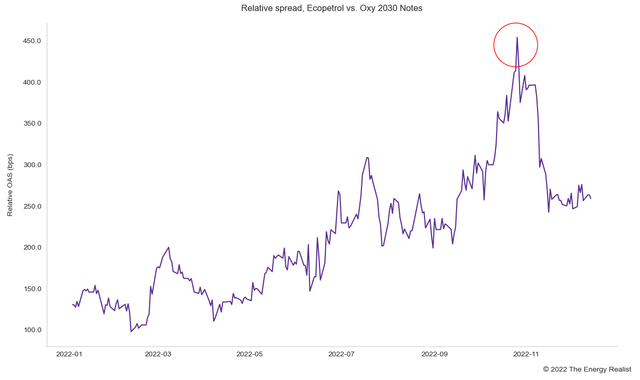

To disentangle the geopolitical component from the selloff in energy, I also calculated a relative spread, pairing Ecopetrol’s notes to Oxy notes with the same credit rating BB+ and also maturing in 2030:

The conclusion is pretty much the same. For more than a month now, the geopolitical risk perception embedded in bond prices has been declining.

The peak in October probably isn’t random either. It coincides with the board of directors drama, when Carlos Cano, the longest serving board member was elected as head of the board. It turned out that Petro hadn’t been consulted, so within 24 hours, Cano’s election was revoked and he was replaced by Saul Kattan, a new board member just nominated by Petro.

The markets reacted very negatively, but in retrospect, this agrees with my analysis. Since Petro is constrained from making substantive changes to the energy sector, it will be important for him to claim symbolic victories in order to appease his base and show he is in control. To my understanding, Mr. Cano is still on the board, and the board head, now Mr. Kattan, doesn’t have many special powers. So Petro’s tantrum over this was probably for domestic political consumption.

Possibly, Petro’s administration didn’t anticipate the market reaction either, because the president’s tweet (in Spanish) shortly after reaffirmed in essence the EC corporate bylaws and their protection for minority shareholders (my emphasis):

1. Ecopetrol configures its board of directors like any other company according to the shareholding, and the majority of shares belong to the State.

2. The new board of directors is made up of people who have already increased the value of companies such as EEB and ETB.

3. The rights of minority shareholders will always be respected.

4. The directive of the President of the Republic for the action of his representatives in the new board of directors is to increase the value of Ecopetrol.

So maybe too much ado for nothing, and that is why CDS and Ecopetrol spreads have come down considerably since the incident.

To conclude the macro review, let’s also take a look at the assessments of Moody’s and Fitch:

Ecopetrol’s Baa3 ratings continue to reflect the company’s status as Colombia’s leading oil and gas producer, accounting for over 60% of the country’s production and close to 100% of the supply of oil products, as well its large power transmission business in Colombia and other countries in Latin America. Furthermore, Moody’s assumes high probability of support from the Government of Colombia (Baa2 stable) and a moderate default dependence between the two entities; this assessment results in a three-notch uplift of Ecopetrol’s senior unsecured rating to Baa3 from its Ba3 (standalone).

Fitch Ratings has affirmed Colombia’s Long-Term Foreign Currency Issuer Default Rating at ‘BB+’. The Rating Outlook is Stable.

Colombia’s ratings reflect the country’s track record of macroeconomic and financial stability underpinned by an independent central bank with an inflation targeting regime and a free-floating currency.

The Gustavo Petro administration pledges to boost social expenditures with key reforms in healthcare, pensions and other areas. Petro’s administration also seeks to transform Colombia’s economy by reducing its dependence on extractive industries while focusing on renewable energy, possibly ending new oil exploration and banning fracking, which if implemented could create uncertainties for the sector and undermine investment.

The president was able to develop a working majority in the congress by achieving alliances with many center-left and leftist parties. As a result, Petro has passed significant tax reform within his first few months in office, which is expected to yield revenues of 1.3% of GDP in its first year and help fund pledged increases to social expenditure.

Policy uncertainties are expected to remain over the coming year. Petro’s reform agenda during 2023 is expected to shift to focus on the potentially controversial pension reform. However, the Petro administration has pledged to adhere to Colombia’s fiscal and monetary framework, adhering to the independence of the central bank and the updated fiscal rule.

Here’s an earlier assessment from Fitch, after the congressional elections at the beginning of the year:

Sunday’s Congressional elections saw no single bloc gain more than 15.6% of the seats in the Senate or 19.6% of the House of Representatives, according to preliminary results…A fragmented Congress makes consensus-building necessary to pass legislation, regardless of who wins the presidency. This supports our view that Colombia’s broad policy framework will remain intact because institutional checks and balances are likely to prevent policy radicalization. An independent central bank and autonomous judicial system will also provide checks and balances to the executive.

Neither assessment suggests reason for panic, and Fitch also highlights Colombia’s institutional constraints as a policy moderation factor.

Conclusion

Ecopetrol’s sound operating performance and heavily discounted valuation make the company a strong deep value prospect. The only factor depressing the valuation is the perception of geopolitical risk associated with Colombia’s new president Gustavo Petro and his environmental agenda.

However, the institutional constraints prevailing in Colombian politics, as well as Petro’s incentives as a now elected official, suggest that the concerns over the government impairing Ecopetrol’s long-term profitability and acting against the minority shareholders may be overblown.

From a macro perspective, the bond and CDS markets also suggest that we may have already seen the peak geopolitical risk perceptions. As the equity markets follow bonds in repricing the risk, Ecopetrol’s shares should rerate higher too.

Editor’s Note: This article was submitted as part of Seeking Alpha’s Top 2023 Pick competition, which runs through December 25. This competition is open to all users and contributors; click here to find out more and submit your article today!

Be the first to comment