piranka

On rare occasions, it is possible to find a value stock that is so underpriced that it trades at multiples that should not be possible if the market is even somewhat efficient. This usually requires a combination of an unusual story that the market hasn’t noticed, and difficult market conditions that depress price multiples. Today, that stock is DXC (NYSE:NYSE:DXC), which may be the most underpriced stock on the market.

In 2015, Hewlett Packard split in two: HP (HPQ), the commoditized business of making PCs and printers, and Hewlett Packard Enterprise (HPE), the relatively more attractive business of selling servers and enterprise services. In 2017, the business was further segmented, leaving the higher margin business of building servers in HPE, and spinning off the lower margin services business and merging it with Computer Sciences Corporation to create DXC Technology.

Today, DXC has 130,000 employees producing more than $15 billion in annualized revenue split almost evenly between two segments. Global Business Services, or GBS, creates and modernizes applications, provides analytics, and offers business process services. Global Infrastructure Services, or GIS, provides IT outsourcing, as well as security services to adapt applications for the cloud, and Modern Workplace, which includes collaboration and device management.

This behemoth has a market cap of only $6 billion. There are two simple explanations for this meager valuation. First, most investors have a growth bias, and DXC had a year-over-year revenue decline of 10.5% in the most recent quarter, though only a 2.6% organic revenue decline after accounting for divestitures. GBS is gradually growing, but GIS has undergone constant pressure from the public cloud offerings of Amazon (AMZN), Microsoft (MSFT), Google (GOOG), and others. However, most industry observers expect the decline in the managed infrastructure market to slow or stop soon as it has advantages over the public cloud for certain kinds of workloads, and in fact polls show that some companies plan to move some things back from the public cloud to private, or use a hybrid solution.

The second explanation for DXC’s low valuation is their EBIT margin, at 7.0% in the most recent quarter, with guidance of 7.0% – 7.5% for the fiscal year. Most investors view low margin businesses as being of lower quality, with less value provided or less of a moat to keep out the competition. Of course, this isn’t necessarily the case; Amazon operates with a low EBIT margin while having a high-quality business.

DXC’s EBIT margin is temporarily depressed by macroeconomic factors, especially those resulting from the war in Ukraine. German and French year-ahead electricity contracts have reached € 1,000 – € 1,100 per megawatt hour, roughly 15 times the low reached before the war. This is a problem for a company that produces billions in revenue from data centers. At the same time, the dollar has strengthened by about 16%, which has lowered DXC’s margins since their costs are more heavily weighted to dollars, while a significant amount of revenue comes in euros.

Without these effects, DXC would have an EBIT margin of over 9% this year. Despite these temporary effects, DXC is guiding for $3.45 – $3.75 in EPS this year, giving them a PE of 7. They are also guiding for $700 million in free cash flow in the current fiscal year.

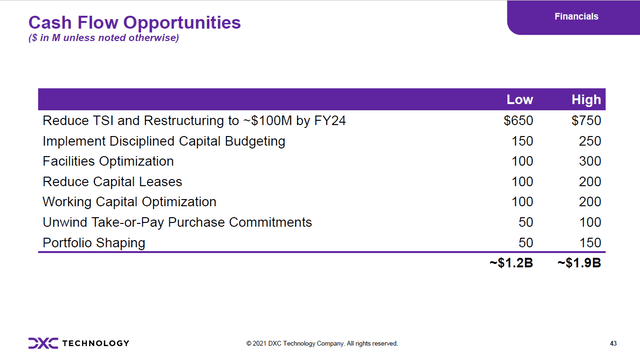

However, this is just the beginning of the profitability story. In September 2019, CEO Mike Salvino joined DXC, followed by CFO Ken Sharp in November 2020. Together they crafted a turnaround plan for a large but shrinking, heavily indebted, and low-margin company. On the growth side, this meant bringing up customer satisfaction, which has recently stemmed revenue declines. On the cost side, this includes reducing restructuring charges, decreasing wasteful capex and consulting expense, bringing contractors in-house, increasing automation, and reducing facility expense.

Before the cost rationalization, DXC was spending a billion a year in facility expense. 40% of that was in offices, and 60% in data centers. 80% of the roughly $400 million spent on offices is being eliminated by going virtual-first, including replacing an 80,000 square foot headquarters building with a 9,500 square foot space. Data centers are also being consolidated to bring them in line with current revenue levels.

In fiscal 2020, 23% of employees were higher priced contractors rather than employees. That number is now down to 12% – 13%, with a goal of reaching 6% in the next fiscal year. They’ve also automated thousands of positions and optimized personnel costs through increased offshoring.

These initiatives result in guidance for fiscal 2024 (beginning April 2023) of 1% – 3% organic revenue growth, $5.00 – $5.25 in EPS with an EBIT margin of 10% – 11%, and FCF of $1.5 billion. At the current price, this would mean a forward PE of 5 and a market cap 4 times next year’s FCF. Management has also hinted that EBIT margins in the low teens are possible in future years.

Of course, free cash flow is useless without efficient use of capital. Fortunately, management has shown consistent good judgment. They sold off several non-core businesses at price multiples above the company average, bringing net debt from $5.5 billion to the target of $2.5 billion. This, along with actions such as getting rid of the oversized headquarters building, shows that management thinks like an investor, prizing returns over ego. After shrinking the debt, they also refinanced the remaining debt at historically low interest rates. Since then, they’ve been repurchasing stock as fast as cash has come in. They’ve spent $900 million to buy back 27.8 million shares, or over 10% of shares outstanding, over the past 5 quarters, and are likely to spend another $500 million by the end of the fiscal year. If this pattern continues in the next fiscal year, then the share count will plummet with $1.5 billion in guided free cash flow for FY24 and only a $6 billion market cap today.

Is this too good to be true? What is the flaw? Some would point to the book-to-bill this past quarter, which was an ugly .87, though the trailing year was a more attractive 1.06. The company’s explanation for the poor bookings this past quarter was that they are continuing to negotiate several large contracts, mostly on the infrastructure side, in order to get better pricing.

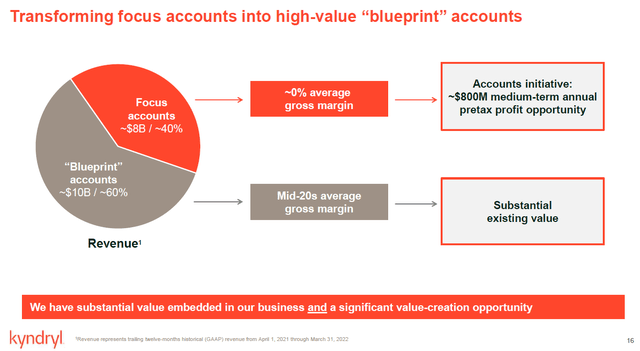

This sounds like just an excuse, but it’s not. To understand why, it’s necessary to look at DXC’s competition. Kyndryl (KD) spun out of IBM (IBM) in November of last year, and is the largest player in the infrastructure market. Kyndryl has slightly higher revenue than DXC, with guidance for $16.3 billion – $16.5 billion for the current fiscal year, with a 0% – 1% pretax margin. In essence, Kyndryl is where DXC was a couple of years ago, and they are beginning their own restructuring journey.

I won’t go into Kyndryl’s restructuring plan in depth here, but one slide is key to understanding the changing pricing dynamic in the industry. 60% of Kyndryl’s revenue is at a mid-20s average gross margin, while the other 40% is at a 0% average gross margin, and that 40% is at a negative operating margin. IBM used those contracts as a loss leader for other parts of the business, and a key part of Kyndryl’s plan is to rationalize the pricing of those contracts when they come up for renewal. They will either be brought up to a reasonable price level or discontinued. Why should Kyndryl do business at a loss?

Atos (OTCPK:AEXAF) is another of DXC’s primary competitors. Atos attempted to acquire DXC for $10 billion in early 2021. The bid was odd because Atos was the smaller of the two and could never afford such a price tag. Atos, like many poorly managed companies, tried to solve their growth problems with an unrestrained buying spree without regard to price. They bought a dozen companies in the 18 months before the DXC bid, and at least 24 companies since 2016. Not surprisingly, this appalling strategy resulted in a change in management.

Atos now has a market cap around $1 billion, or a sixth of DXC’s, with around $11 billion of revenue last year. Atos recently reported a 1.1% operating margin, and is guiding for an operating margin of around 3%, despite improving margins with some higher margin acquisitions in past years. Atos recently completed a refinancing and is now contemplating a spinoff, splitting the company in half so that the boring stuff is in one company and the higher growth businesses are in the other. Like Kyndryl, you might say that Atos is where DXC was a couple of years ago, or even further behind, since the future of the company is still under consideration.

None of these companies have any motivation to sign contracts with customers at past pricing, with low or even negative operating margins. This is reminiscent of the way the DRAM industry consolidated to a point where they could finally command a higher margin for their products. Ironically, in this case, it’s not consolidation that brought this about, but spinoffs. In spinning off less attractive businesses, poor business practices were revealed for what they were. A key part of this process is ditching the sunk cost fallacy, in this case by choosing new CEOs and CFOs who aren’t using motivated reasoning to justify past poor decisions, and by eliminating the anchoring bias, as past managers may have anchored to the poor margins in current contracts.

As I explained in my recently published book, Rational Thinking and Investing, spinoffs also show the less-is-better effect. With the less-is-better effect, people irrationally compare things according to a reference point rather than an objective measure. For instance, people may value a scoop of ice cream that completely fills a small bowl more highly than a larger scoop that is in a much larger bowl that appears to be half empty, because people value it by how full the bowl is rather than an objective measure of how much ice cream they are getting, as long as they don’t see both bowls of ice cream at the same time. This effect is why restaurants use garnish with meals, to give the illusion of a full plate and the feeling of better value for the money.

In one experiment that showed the less-is-better effect, one group of people valued a set of 24 dishes at $32.69, while another group valued a set of 31 dishes (including the 24 from the first set) plus nine additional broken dishes at $23.25. The presence of the extra broken dishes made the people feel that the set was flawed, and so they lowered their subjective valuation of it, rather than valuing it objectively with a sum-of-the-parts method, and this resulted in a lower valuation for 31 dishes compared to just 24 dishes. Companies with a flawed or less attractive division are often misvalued the same way, showing the less-is-better effect, and spinoffs often rectify this by separating out a part of the company, leaving the higher quality part untarnished by the lower quality part.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting that this is a good reason to conduct a spinoff. Management should only conduct a spinoff to create value, not to change investor perception, because it is management’s job to make profit, not to manipulate investor psychology.

Regardless of the motivation for the spinoffs in the cases of DXC, Kyndryl, and Atos, the effect has been to reveal opportunities to cut costs and to price contracts reasonably. DXC is now led by management that is focused on pursuing efficient operations and allocating capital well. The current price doesn’t reflect this, with a forward ~25% FCF yield. You’ll be hard-pressed to find a more underpriced stock, even in these strange times.

Be the first to comment