Justin Sullivan

This article was coproduced with Chris Volk, author of The Value Equation.

As my readers know, I’m a real estate investment trust (“REIT”) “guru” on Seeking Alpha. Over 100,000 people here follow my insights to get a better understanding of these commercial property holders.

I’m also the author of three published books – all on real estate – and an adjunct professor at New York University who teaches about… wait for it… real estate! Through all of that, I constantly preach about staying inside one’s wheelhouse when investing.

It’s a very good rule of thumb, especially for “newbies.” But I will admit that, from time to time, I enjoy venturing into other sectors that could benefit readers.

So that’s what I’m doing here today with the help of Chris Volk. Author of The Value Equation, he knows a thing or two about what we’re talking about today.

Real Estate Glue

I enjoyed putting models together as a kid. So I guess I was meant to build as an adult, first commercial real estate and then portfolios.

That initial leg of my professional journey allowed me to appreciate how critical real estate is for most businesses to profit.

Take Starbucks (SBUX), a wonderful business I bought shares in years ago. Much of its revenue is generated at physical locations.

Or NIKE (NKE), which I also bought. It relies on real estate to manufacture the merchandise and sell most of its shoes, too.

And consider how many companies under Warren Buffett’s flagship Berkshire Hathaway (BRK.A)(BRK.B) can say the same…

- See’s Candy – manufacturing and retail stores

- Pilot Flying J – convenience stores

- Nebraska Furniture Mart – retail storefront

- Fruit of the Loom – manufacturing and logistics

- Dairy Queen – fast-food

- Apple (AAPL) – big tech

- Bank of America (BAC) – bank

- STORE Capital (STOR) – net-lease retail.

I’m just getting started…

Real estate is the proverbial glue for many businesses to brainstorm, research, manufacture, store, and distribute. That’s why it’s the third-largest asset class in the U.S. investment market.

Of course, businesses don’t have to own their buildings. They can rent instead, and that can be a very viable choice.

That often sets it apart from residential property. One of the great things about owning a home in the U.S. is the financial benefits, such as:

- Mortgage interest deductions

- Property tax deductions

- Deducting private mortgage insurance.

Appreciation is another huge win for homeowners, especially as property values skyrocket. For instance, I purchased my home around 10 years ago for $500,000…

Today, it’s worth an estimated $650,000 with about a 3% compound annual growth rate (“CAGR”). Plus, I get to deduct interest and taxes.

The perks of ownership aren’t always as well-defined with commercial real estate though…

The Sale-Leaseback Concept

One way to unlock value in free-standing real estate is to utilize a method known as sale-leaseback.

It involves a company selling its property to a landlord – then signing on with said entity via a usually long-term lease – in order to earn a higher return on its core business compared to investing its capital in owned real estate. That’s something almost all companies can potentially benefit from.

Many companies skip ownership altogether, simply arranging to have property developed that’s then bought by landlords from the get-go. That’s because they recognize the advantages to renting.

It makes it easier to allocate capital and, in many cases, manage residual real estate risk. Leasing versus owning is a corporate capital stack choice.

After all, owning likely requires:

- Getting secured bank financing

- Committing an equity investment equal to 25%-40% of the property investment.

Electing to use a landlord, meanwhile, means 100% of the property can be financed, requiring minimal to no equity on the tenant’s part. It also tends to have lower payment requirements than debt, owing to how landlords aren’t expecting to be fully paid back.

They’re undertaking residual risk.

Given this analysis, you can think of net-lease REITs – which are experts in the sale-leaseback transaction – as effectively “shadow banking” companies. Their ownership of real estate provides a financial service to their tenants.

A few notable sale-leaseback buyers in the REIT sector include Medical Properties Trust (MPW), Innovative Industrial Properties (IIPR), and Realty Income (O).

Though one of the earliest pioneers of this structure is the New York-based W. P. Carey Inc. (WPC). It’s amassed an $18 billion (enterprise value) portfolio spread across 25 countries.

As such, it’s well worth digging into further.

A Great Idea That’s Taken Off

W. P. Carey’s founder, William Polk Carey, learned how to lease back when he was a freshman at Princeton. There, he discovered that he owned something many of his schoolmates did not – a small dorm-room refrigerator.

Seeing an opportunity, he purchased as many refrigerators as he could afford and leased them back to his schoolmates for a small fee. By the end of his sophomore year, he had made over $10,000.

It was this simple idea that laid the groundwork for the concept of the sale-leaseback.

Today, this once-niche method of finance is hotter than ever. The pandemic accelerated the trend as certain businesses recognize that working capital is limited… lending guidelines are more stringent… and merger and acquisition (M&A) activity is accelerating.

These conditions represent a strong environment for sale-leasebacks.

Another catalyst is how C-corps can’t spin their real estate holdings into REITs anymore. The last such transaction was when restaurant giant Darden (DRI) formed Four Corners Property Trust (FCPT) in 2015.

After that, the IRS nixed the practice, leaving interested businesses with limited options.

Here’s the thing: It’s not just the landlord that benefits from a sale-leaseback. The owner-occupier also gains more flexibility to retain its space and operations.

I know real estate ownership sounds like it provides operators with a greater degree of control. But lender constraints can often be more limiting than those of landlords.

The building’s sale boosts a company’s financial reserves. And more cash on the balance sheet can be useful in reassessing one’s approach to a post-pandemic world.

Obviously.

The Profitability of the Sale-Leaseback Proposition

It’s also worth noting that investors can be more motivated to increase their offering price if a seller is willing to lease more space at longer lease terms.

Take casinos, for instance. The prices paid by landlords can often exceed asset construction cost. Essentially, landlords are paying for the entitlement and comfort of their position in the tenant’s capital stack.

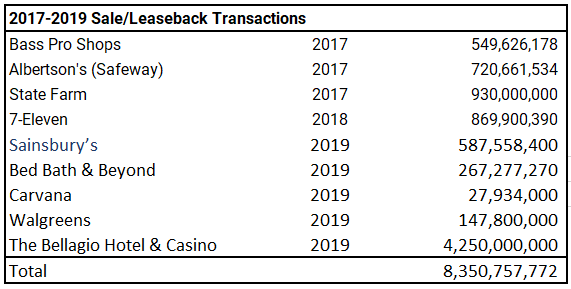

(iREIT on Alpha)

(iREIT on Alpha)

Jon Hipp, head of U.S. Net Lease Group with Avison Young, explains:

“[sale-leaseback] transactions are particularly beneficial, sometimes even a necessity, for companies that have exhausted their lines of credit or don’t qualify for traditional lending in the current economic environment.

“Companies clean these assets off the balance sheet with SLB financing (referred to as off-balance-sheet financing) to create liquidity. In uncertain economic times, liquidity is often what decides whether the business continues operations.”

“The leases are triple-net leases in which the tenant handles everything. This making it a predictable, low-maintenance income stream for the new landlord. The most active buyers have been publicly traded REITs with low cost of capital.”

All of this brings us to Kohl’s Corporation (NYSE:KSS) – and the recognition that I didn’t stray so far from my wheelhouse after all.

The Kohl’s Real Estate Empire

You might recall how, recently, Franchise Group (FRG) scrapped its plan to acquire Kohl’s for $50 per share. What you might not know is that the proposed enterprise value was heavily centered in the chain’s real estate value.

Kohl’s is an investment-grade retailer that elected to own real estate – or the buildings situated on ground leases – for approximately 55% of its 1,165 locations. That’s a large part of why it has the BBB- rating it currently does.

Yet real estate ownership for high-volume, low-margin, asset-heavy retailers is a difficult prospect. It demands a high-equity mix. Even higher in Kohl’s case.

At the same time, investor equity return requirements for high-volume, low-margin, asset-heavy businesses demands allow equity mix. Which has not been the case at Kohl’s.

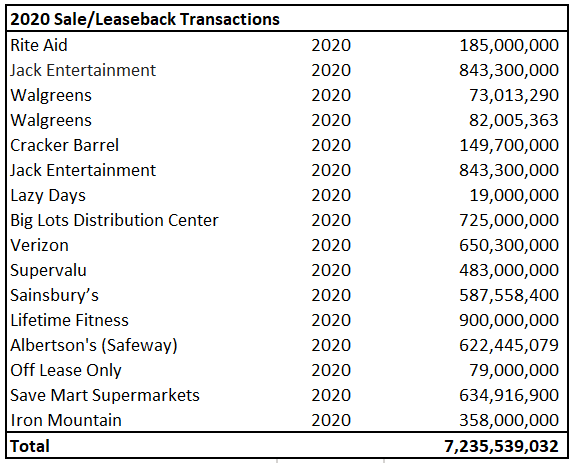

(Chris Volk)

Looking at the cost-basis of its December 31 balance sheet, Kohl’s has an equity/debt mix of assets that must be funded at around 76%/24%.

This doesn’t tell the whole story behind the company’s capital stack though. It excludes the landlord proceeds used to lease 45% of its locations – and roughly 20% of its locations where landlords provided the land and Kohl’s owns the building.

How did the asset-heavy, high-volume, low-margin Kohl’s get to where it is?

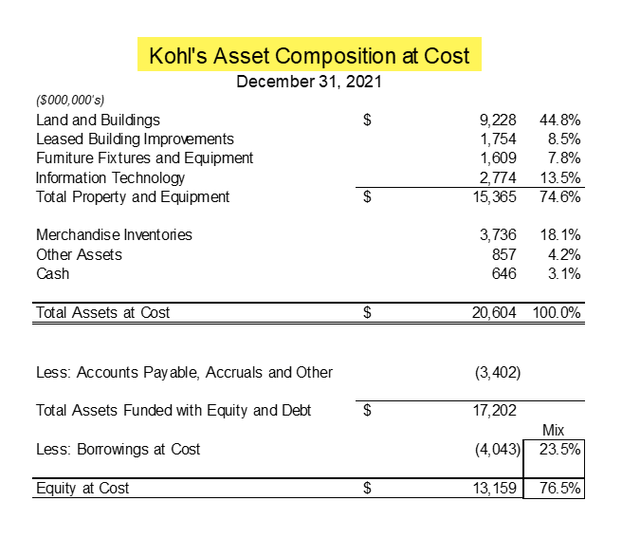

Well, in June 1992, when it first went public, it was trading at a price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple around 29x. That would peak at 149x in January 1999 before gradually sliding to around 20x in July 2007.

Following the Great Recession, it steadily declined even further to now stand at a meager 4.5x.

The inverse of a P/E multiple is an income equity yield. In which case, 20X is effectively 5%.

Assuming real estate landlords or lenders would have expected yields higher than this through July 2007… real estate ownership could be more accretive to short-term earnings.

Kohl’s Is a Great Example of the Real Estate Game Played Badly

Of course, what looks to be a wise decision in the near-term can be a poor decision later on. And so Kohl’s election to have an equity-heavy, investment-grade, real estate-laden capital stack proved a problem.

As of December 31, it had assets at cost of more than $20 billion against borrowings. and other obligations of approximately $7.4 billion. That made its equity at cost equal to roughly $13.2 billion.

We’re using Kohl’s December year-end financial statement because it contains greater asset detail. (Its equity at cost wasn’t materially different at the end of Q1-22.) Given a current equity capitalization approximating $3.2 billion, Kohl’s has lost approximately 75% of the cost of its deployed equity.

Question: How does a company light that much money on fire?

Answer: By realizing equity rates of return from its business model that are well below shareholder expectations.

Some of this lack-of-return-driven loss has no doubt been from competitive pressures and management decisions. But a great deal of it was due to Kohl’s misguided decision to become an investment-grade company with so much real estate.

It has a poorly designed capital stack.

Chris Volk |

Today, Kohl’s is trading below its book value – which, incidentally, doesn’t account for approximately $8.2 billion in accumulated depreciation. Which is where its losses lie.

Depreciation is an accounting convention that does nothing to alter a company’s actual investment in its assets. And all successful companies have one thing in common: they have enterprise values worth more than the cost of their assets.

Unfortunately, this is far from true with Kohl’s. With every new store opening, it’s been lighting money on fire.

Working the Numbers

Now, here’s where my REIT expertise really comes into play.

With REITs, adjusted funds from operations (AFFO) excludes depreciation, which is viewed as a non-cash, non-cost expense. Likewise, accumulated depreciation isn’t factored in when looking at real estate investments or assets at cost.

With so much invested in real estate, Kohl’s isn’t really a prototypical retailer. It’s somewhere between a retailer and a REIT.

Actually, it’s more the latter since owned retail real estate comprises about 45% of its assets… but closer to 55% of the net assets that have to be funded with borrowings and equity.

How much might Kohl’s real estate be worth?

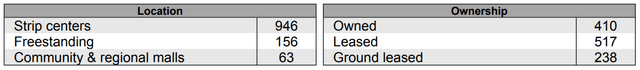

As previously stated, it has 1,165 locations: 410 owned sites, 517 leased sites, and 238 ground leases. 946 of these sites are in strip malls, 156 are free-standing, and 63 are in malls.

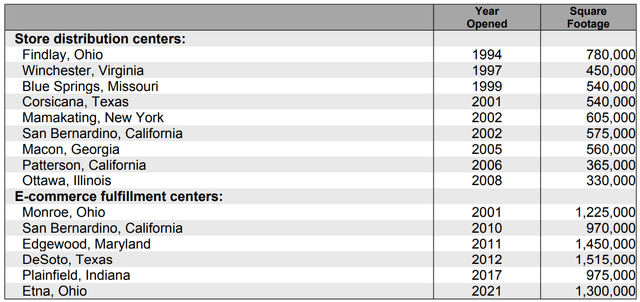

It also owns all the distribution and e-fulfillment centers below (except for the San Bernardino, California and Corsicana, Texas locations, which are leased).

Thus, the owned real estate is summed up as follows:

- Owned stores: 410

- Ground Leased: 238

- Industrial properties: 12

Meanwhile, the average selling space for the retail units is around 70,000 square feet. For modeling purposes, I’m using $10.00 per square feet (“NNN”) for the sale-leaseback.

-

- 70,000 sq. ft. (i.e., one store) x $10.00 = $700,000

- ÷ a 7.5% cap rate = $9.3 million per fee store value

- x 410 locations = $3.8 billion.

The 7.5% cap rate is in recognition that Kohl’s would be non-investment grade after unloading its real estate. Though the replacement costs of the individual locations would likely be higher than our final tally above.

In addition to its fee locations, Kohl’s leases the land beneath 238 stores, or about 20% of its locations. Ground leases are the worst of all worlds because Kohl’s had to pay for buildings it will never truly own.

When the ground leases ultimately mature, the buildings’ title will transfer to their landowners. Getting landlords to buy these assets and then lease them back to Kohls is therefore trickier.

Their value rests in the thought that the land lease obligations represent a substantially below-market lease. However, if a landlord has to repossess a property, they’ll have the obligation of paying the ground-lease rents while trying to find a replacement tenant.

Often, these landlords will even have to become ground-lease obligors as opposed to simply having ground-lease assignments.

More Kohl’s Numbers to Know About

For the sake of argument, I’m using an average building rent of $250,000 for those properties. That and a higher going-in cap rate of 9% to account for the buildings having no residual landlord value.

This gets you to about $2.8 million per building multiplied by 238 locations. And that results in a value of $661 million, which definitely represents a discount to replacement cost.

Finally, the 12 industrial sites average around 900,000 square feet, and I used an annual rent cost of $7.00… which translates into annual rent of $75.6 million. Industrial cap rates are trading in the mid 4’s, which then puts Kohl’s industrial portfolio at a meaty $1.7 billion.

Thus, the sum of the parts is $6.2 billion, and Kohl’s has new lease liabilities of $422.1 million (excluding taxes, insurance, and maintenance).

Assuming it unloaded its owned real estate for the tune of $6.2 billion, it could pay off all its around $4 billion in debt – with room left over!

Of course, it will need some of that to address:

- Transaction and early extinguishment of debt costs

- Taxes that might result from real estate sales priced above their underlying tax basis.

With retailers having higher valuations, taxes on the recaptured depreciation and real estate gains could be material. This is where a company might look to realize a tax-free real estate spin.

Though probably not Kohl’s. Its decimated valuation will likely diminish tax consequences.

For existing Kohl’s landlords at the company’s 517 leased sites, its subsequent credit-rating loss would likely result in a loss of investment value. This, I suppose, demonstrates the risk of paying up for real estate leased to investment-grade tenants.

Winding the Current Kohl’s Story Down

At $29.17 per share, Kohl’s current market equity is around $3.8 billion.

Yet the last offer from The Franchise Group was $50.00 per share. That translates to $6.4 billion and an enterprise value of around $10 billion.

Based on a conservative $6.2 billion real estate valuation, the equity required to consummate the transaction would approximate $4 billion+. So the trick for any acquiring company will be to move as much of the $10 billion to the real estate as possible…

Then layer on some senior corporate borrowings that effectively represent financing for the company’s IT and furniture fixtures and equipment.

Still, even with my conservative estimates, real estate value comprises approximately 60% of enterprise value. Once again, this demonstrates that Kohl’s is more REIT than retailer.

One thing a prospective buyer won’t want to do is leverage Kohl’s massive inventory. A common characteristic of recent leveraged retailer failures has been the use of asset-based credit facilities.

These can be useful for short-term needs, but dangerous if used as long-term financing.

Take Toys “R” Us. The ABL lenders were unwilling to diminish their position. That left it no assets to induce credit-facility-possessing debtors to attempt a recovery.

Doubtlessly, Toys “R” Us had plenty of profitable locations left. But it never had the chance to prove it.

In Conclusion…

Absent an acquisition, we strongly encourage Kohl’s to seek a sale-leaseback of its real estate.

Based on our rough estimate, this could allow it to pay off its debt. From there, it could either pay out a $2 billion special dividend to its shareholders or effect a share repurchase.

Or, unlike The Franchise Group, Kohl’s could retain some of its debt outstanding. Regardless, the result would be to do what it should have done years ago: lease its real estate.

It won’t be able to recover all its lost value, it’s true. But right-sizing its capital stack would be a start in the right direction.

I’m sure this sounds familiar, considering the Sears saga. Seritage’s (SRG) board has recommended a sale of assets and dissolution of the company.

But what if Sears pursued a strategy to be more asset-light instead of real estate-heavy?

And what about Target (TGT)? It owns a ton of real estate, too.

Why doesn’t it use its highly sought-after real estate to buy beaten-down shares?

But we’ll save that for another day. So stay tuned!

P.S. Here’s our latest on Franchise Group.

Be the first to comment