Paul Morigi/Getty Images Entertainment

“You make most of your money in a bear market; you just don’t realize it at the time.” – value investor Shelby Davis

Get ready for a shock. The book value of Berkshire Hathaway (NYSE:BRK.A)(NYSE:BRK.B) is in the process of falling by a scary amount. That will become apparent in about a month when it reports second quarter earnings. There are a few underlying reasons but very few companies have the unusual degree of exposure to a huge downward reset of valuations. The bear market will weigh on both reported net income and the balance sheet even as its fundamentals remain solid. Don’t panic. It may weigh upon the Berk stock price for a while, but as Buffett has said, “The best chance to deploy capital is when things are going down.” Recognizing a tough period for Berkshire should lead smart investors to start thinking about levels at which to buy. Times like this are when you set yourself up for future profits – in Berkshire and many other investments.

For most businesses, earnings may be a little punk for a while but little or no change in book value will result. Berkshire is different. You can chalk it up the outsized impact on Berkshire to Accounting Standards Update (ASU) 2016-1 which went into effect in 2017. The new rule required the inclusion of “unrealized investment gains and losses” in reporting Net Income. This greatly expanded the previous rule mandating that “realized capital gains” be included in reported income. CEO Warren Buffett pointed out in Berkshire’s 2017 Shareholder Letter that the inclusion of unrealized gains and losses had the effect of creating “wild” and “capricious” numbers which had to be included in all net income figures and thus made the bottom line number “useless.” Ironically, the for 1917 results an equally extraneous event, the corporate tax cut, was juiced earnings as he stated in paragraph one of the Letter:

Berkshire’s gain in net worth during 2017 was $65.3 billion, which increased the per-share book value of both our Class A and Class B stock by 23%. Over the last 53 years (that is, since present management took over), per share book value has grown from $19 to $211,750, a rate of 19.1% compounded annually.

The format of that opening paragraph has been standard for 30 years. But 2017 was far from standard: A large portion of our gain did not come from anything we accomplished at Berkshire. The $65 billion gain is nonetheless real – rest assured of that. But only $36 billion came from Berkshire’s operations. The remaining $29 billion was delivered to us in December when Congress rewrote the U.S. Tax Code.”

Decoding Buffett’s objective wording, the message is that shareholders and analysts should not take the nominal number too seriously. What they should do instead is base their view of Berkshire on the much less variable number of $36-39 billion cash from Berkshire’s operations. Buffett had in fact never really approved of including “realized” capital gains or losses as part of earnings because they were erratic and random, thus providing a poor measure of long term growth and profitability. It took less than a year for a market decline stopping at just under 20% showed what the ASU 2016-1 rule could do to book value in a bear market.

In this article, published on December 24, 2018, I pointed out that the decline including the few remaining trading days of 2018 might pull down the stocks in the Berkshire portfolio by as much as $37 billion. It turned out to be a little less as stocks rallied between Christmas and New Year’s, but it was still quite bit at a time when Berkshire’s entire stock portfolio was a mere $177 billion. The stock portfolio was also much smaller compared to Berkshire’s operating divisions than it was on December 31, 2021.

My first concern in 2018 was that Berkshire’s price to book value (P/B) ratio would jump from 1.25 to 1.41. Book value was still a major metric for Berkshire and investors still looked to the P/B level when trying to estimate the level of buybacks. A major leap in the P/B ratio would test the underlying assumptions of Buffett’s new, more fluid buyback policy. Would he ignore the jump in price to book and stick to his often expressed view that Berkshire owned stocks as businesses which paid Berkshire dividends and also produced “look through” earnings creating retained earnings which internally compounded their value?

As it turned out that was exactly what happened as Buffett signaled his deemphasis of book value in the 2019 Shareholder Letter dropping it from the page one comparison of long term returns with the S&P 500. His stated rationale was book value had become less meaningful since Berkshire had an increasing weight of wholly owned businesses which had grown tremendously but remained on the on the books at their original purchase price. The better way to look at both businesses and publicly traded stocks was “business value,” the cash dividends returned to Berkshire corporate headquarters as well as the earnings that both internal subsidiaries and publicly traded stocks retained and which would provide future earnings growth. The Accounting Standards Board didn’t see it that way and instead mandated that “unrealized capital gains and losses” be included in Net Income, thus also dropping down into Book Value. The effect on both would be dramatic, though mainly cosmetic, for Berkshire. The 4th quarter of 2018, with the Fed initiating a series of rate increases, put it to the test. Here are the top six stocks in the Berkshire portfolio I considered in 2018 along with my predicted hit to book value:

- Apple (AAPL) – roughly $19 billion

- Bank of America (BAC) – roughly $5 billion

- American Express (AXP) – a bit over $2 billion

- Kraft Heinz (KHC) – a bit under $3 billion

- U.S. Bancorp (USB) – a bit over a half billion

- Wells Fargo (WFC)- about $4 billion

Thanks to strong operating earnings Berkshire’s book value was essentially flat for 2018. After the one-quarter almost-bear market the Fed backed off and the bull market resumed. It is likely to be different this time.

There’s An Important Nuance Of Difference In 2022

It’s a little early to close the books on Q2 2022, but at this point we can take a stab at what the decline in book value might be. It should be noted that the 2018 and 2022 events had a major difference in the nature of the stock market decline. In 2018 the Fed attempted to tighten and increase rates and the market as a whole fell a little under 20% with most stocks going down in unison. The decline took place over about 30 days.

In the current bear market prices of various groups have declined in sequence starting about 15 months ago in February 2021 with ARK Innovation ETF (ARKK) and the speculative stocks it contains, then moving to more substantial but overpriced tech stocks like Amazon (AMZN) and Alphabet (GOOG)(GOOGL) in November 2021, and growth stocks in general such as those in the Invesco QQQ ETF (QQQ) at the beginning of 2022.

Until the beginning of 2022 the market had two trends: (1) a general decline which began with insubstantial Cathie Woodish companies and (2) a gradually broadening decline with a focus shifting from overpriced growth to moderately cheap or less overpriced value. Around the end of the first quarter, on March 31, the bear market finally came for the value side of the market. Their steeply declining prices quickly began to play catch-up with the market as a whole.

The numbers stem from different dates but all the stocks below peaked in 2022. The total hit to book value from the first trading day of 2022 is $85 billion. Bear in the mind that there are two weeks left in the second quarter and prices are changing even as I write this. Here are the current top six stocks in the Berkshire Hathaway portfolio with their approximate amount down from all-time highs. All fall into the category of value. They amount to about 75% of the Berkshire portfolio.

- Apple $60 billion

- Bank of America $11.5 billion

- Coca-Cola (KO) $1

- Chevron (CVX) down $3 billion

- American Express billion $4.5

- Occidental Petroleum (OXY) down $5 billion

BAC was the first holding to drop hard and persistently along with all the other banks. I would speculate that BAC and other banks will be among the first parts of the market to recover because their extremely low P/E ratios should provide support. AXP is down surprisingly hard, falling 30% since mid-February. KO, down about 10% like other highly valued consumer staples stocks, was among the last to decline, starting in April. Chevron and Occidental were at all-time highs less than 10 days ago but have fallen 22% and 24% as of the moment I am writing this line.

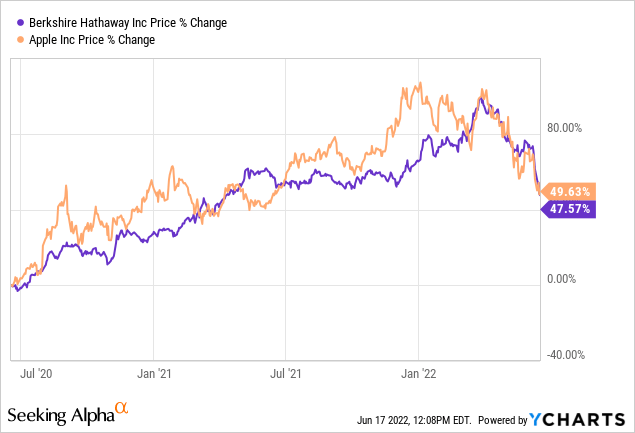

Apple and Berkshire itself are the most interesting. Apple peaked on the first day of trading in 2022, January 3, but bounced strongly twice, trading within a dollar of its January high at the end of March before succumbing to a steep decline. Berkshire Hathaway peaked on March 31 and has fallen relentlessly since. The behavior of AAPL and BRK.B aren’t surprising. Both are the most stalwart of market stalwarts. AAPL has an unmatched consumer brand and BRK.B sets the standard for steady and persistent long term gains and equally steady, capable, and shareholder-friendly management. What’s not to like? Nothing, except as the last survivors Apple and Berkshire had both become expensive in both absolute and relative terms. Here’s a chart showing both:

Looking back two years Berkshire and Apple are virtually in lockstep. For Berkshire, that presents a bit of a double whammy. Despite its steep decline since March 31, Apple leads a decline in book value which assures that Berk’s P/B has not declined as sharply as one might think. Is that dragging down Berk’s steep relative decline at this point or is Berk just continuing to play catch-up in a steeply declining market?

The Base Case For Owning Berkshire Hathaway

Berkshire is a conglomerate, but it is very different from conglomerates fifty years ago which were thrown together by acquirers using debt and their own inflated stock for currency to pump up their stock price with mediocre acquisitions. Berkshire was carefully put together and Buffett’s major units are uniformly high quality. The overall structure combines decentralized management with centralized asset allocation done largely by Buffett himself. That being said, Buffett’s designated successor has played an important role in recent acquisitions, and his two stock managers have been successful running a growing amount which is now about $70 billion. Management overall is excellent and deep.

To understand Berkshire Hathaway you start with the fact that its earnings and overall value come from several distinct but interconnected areas. Its four operating units – Insurance, the BNSF Railroad, Berkshire Hathaway Energy, and the Manufacturing, Service and Retail Unit – are made up of wholly (or largely) owned subsidiaries acquired over fifty years. Its publicly traded stock portfolio originated as a vehicle to invest insurance float to pay future insurance claims. Its largest position by far is Apple, with a year end 2021 value of $161 billion. Buffett sometimes describes as its second largest business unit.

Net earnings attributable to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders from the four business units and stock portfolio for each of the past three years are disaggregated in the table that follows. Amounts are in millions after deducting income taxes and exclude earnings attributable to non-controlling interests. What remains are the numbers for actual operating earnings. That’s the number Buffett believes analysts should start with.

|

2021 |

2020 |

2019 |

|

|

Insurance – underwriting |

728 |

657 |

325 |

|

Insurance – investment income |

4,807 |

5,039 |

5,530 |

|

Railroad |

5,990 |

5,161 |

5,481 |

|

Utilities and energy |

3,495 |

3,091 |

2,840 |

|

Manufacturing, service and retailing |

11,120 |

8,300 |

9,372 |

|

Investment and derivative gains/losses |

62,340 |

31,591 |

57,445 |

|

Other* |

1,315 |

(11,318) |

424 |

|

Net earnings attributable to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders |

89,795 |

$42,521 |

$81,417 |

|

Operating Earnings |

26,140 |

22,248 |

23,548 |

Table extracted from Berkshire Hathaway 2021 Annual Report, p. 32.

For the bottom line of the table I subtracted the numbers for Investment gains/losses and Other. Another important number not included in the table is free cash flow, which has been about $36-39 billion in recent years. To get to the numbers in the bottom line of the table one subtracts aggregate capital expenditures of the operating businesses. Cash flow has doubled over the past decade. That’s a faster rate than the ten year increase in net earnings with a one-time jump from the corporate tax cut of 2017. Depending on the degree to which profits are squeezed by the current inflation the numbers for both earnings and cash flow should generally grow at a moderate rate.

Assembling a definitive number for the value of Berkshire Hathaway is difficult. This SA article by David Kass took a shot at it using a relatively simple methodology. I have resisted the temptation to do an article valuing Berk two or three different ways but two of my past Berkshire articles, here and here, touch upon the subject tangentially and also lend themselves to the discussion of future buybacks later in this article. Arguably one might value the separate businesses by the standard business school approach of comparing them to separate free standing businesses. The catch is that valuations are now in flux due to the complexities that stem from insurance underwriting and insurance float. There are also complications involving the way to think about the publicly traded stock portfolio.

You get a sense of the difficulty in the fact that some sector divisions count Berkshire as a financial while others classify it as an industrial. The exceptional events of the past few years, including the pandemic lockdown, an actual change in the corporate tax rate as well as the impact of Accounting Standards Update (ASU) 2016-1, produce unhelpful numbers which must be smoothed in a process involving estimates. On top of those factors, Berkshire’s annual results are inherently lumpy.

Three years ago, I calculated Berkshire’s Return on Equity as slightly above 9% and noted that buybacks, which reduce the ROE denominator, could lift ROE above 10% within a year or two. I think the pandemic crimp to earnings and slowing buybacks because of Berkshire’s price run-up took that off the table. Over the long run, however, looking at its separate businesses and its stock portfolio as measured by dividends (and perhaps by the increase in retained earnings) earnings should compound at a rate a little under 10%. Tax increases, wars, and pandemics could of course completely wreck this forecast.

SA Rating Summary, Factor Grades, and Quant Rankings are not as helpful for Berkshire as for most stocks in part because the overwhelming majority of Berkshire investors view it as a long term core holding. Berkshire’s Rating Summary at SA is Hold, which happens to be what most Berkshire investors do. Berkshire is more popular with SA authors and Wall Street analysts who rate it a cumulative Buy. None rate it a Sell. The Profitability Grade of A+ is the Factor Grade which stands out. Berkshire’s Profitability Factor Grade appears to depend heavily upon the $37 billion gusher of Cash From Operations. Cash flow like that overpowers other metrics which are distorted by the various factors mentioned above. That’s the amount Buffett has available to reinvest or reallocate on an annual basis.

Will Future Berkshire Buybacks Return To A High Level?

A large market decline presents huge opportunities but difficult choices. The choices presented to Buffett are pretty much the same as the choices presented to you and me. Buffett’s priorities for deploying that flood of cash are the following in order of preference:

- Increase the long term earning power of Berkshire’s controlled businesses through internal growth (something you and I can’t do) or by making acquisitions. Many lists of alternative uses for cash separate internal CAPEX from acquisitions.

- Buy non-controlling part-interests in good businesses that are publicly traded (i.e., buy stocks). At the recent Annual Meeting, Buffett saw few exciting prospects. That is clearly changing.

- Repurchase Berkshire Hathaway shares when they are available at good prices, thus increasing your share of the many controlled and non-controlled businesses plus publicly traded stocks that Berkshire owns. Buffett calls this the easiest and most certain way to increase shareholder wealth.

In the last couple of years, since he completed establishing his position in Apple, Buffett purchased such things as bolt-on additions to Berkshire Hathaway Energy, value stocks paying good dividends, and most recently the energy companies Occidental and Chevron. The bolt-on include pipelines and a storage facility bought from Dominion Energy (D) and Alleghany Corporation (Y) which fits seamlessly into Berkshire’s insurance businesses. Bolt-ons are almost always successful because they are businesses you already know a lot about. Stocks bought for cash dividends mainly to pay future insurance claims include the five Japanese trading companies, which he carefully hedged by issuing debt in yen, and HP Inc. (HPQ), a slowly fading tech stock with a good dividend.

If the reset of valuation continues I suspect that Buffett’s focus for acquisitions and publicly traded stocks may shift toward established growth stocks which are rapidly falling toward reasonable prices. My first thoughts are Amazon and Alphabet (now with a 19 P/E), although there may soon be a large list. The question is how newly cheap or reasonably priced growth companies will stack up against Berkshire itself. Apple shows what an astute tech investment at the right price can do to juice returns. But what about the steady growth of the company Buffett knows best?

The 2020 and 2021 level of Berkshire buybacks took place in an environment in which Berkshire itself was the surest and safest candidate. The case for Berkshire includes but is not limited to the following:

- Its large operating units are not going away anytime soon and have a more or less assured growth that should more than keep up with the economy.

- These businesses and Berkshire as a whole are well within Buffett’s area of competence.

- The insurance businesses are in the aggregate best of breed and relatively immune to economic downturns.

- Buybacks help make the case against dividends, which the overwhelming majority of Berkshire shareholders don’t want (to me and many others they mean throwing money away as a gift to the IRS). Shareholders willing to take minimal action can convert buybacks into a dividend up to the percentage of shares repurchased at a lower tax rate and without reducing the percentage of Berkshire Hathaway owned.

The following bit extracted from the second of two past articles cited above shows how a buyback works:

The $24.7 buyback in 2020 amounted to 5% of Berkshire’s total market cap. This had the effect of shrinking tangible book value by that same $24.7 billion. Cash, of course, is very tangible, despite the fact that it currently produces no return. Lowering the denominator without change in the numerator lifted the rate of return to its present 9.8%. Meanwhile the few Berkshire shareholders desperate for a dividend had their wish fulfilled: they could sell 5% of their shares without diluting the percentage of ownership they had before the buybacks. Here’s a quick review of the effects:

- The shares remaining after the buyback were 95% of the shares previously outstanding.

- Continuing shareholders now own 5.2% more of Berkshire’s total cash flow and earnings than they did previously.

- All per share measures except P/B increase by that same 5.2% – the equivalent of a 5.2% addition to growth.

- Return on Book Value moved closer to reflecting Berkshire’s actual level of profitability.”

The beauty of this use of cash is that the benefits are structural and not dependent on anything else. They won’t, of course, produce a home run like Apple but they won’t risk a big loser either. The overall return is a little better than the internal return at Berkshire itself. Factoring in the relative safety, that’s excellent.

How To Buy Or Add In Stages

Berkshire began 2022 trading around $300 per share and went more or less straight up. That $300 price did not stop Buffett from buying although the level of his purchases was reduced. In the 4th Quarter of 2021, however, he bought back $6.7 billion in shares at prices which probably averaged around $290. Berkshire looks like a long term buy anywhere below that price. As I write this it is trading at $270. That’s clearly below fair “business value.” I would buy or add at least the first third of the capital I wished to deploy.

At $250 I would buy the second third, confident that this buy would look good in a year or two. At $220, if that price should at any point be available, I would go all in. $220 is a steal.

I’m not saying you should put all your cash into Berkshire. You should also consider, just to name two areas, the established growth stocks mentioned above and financials, the most obvious being major banks, my favorite being Bank of America. But that’s another story and another article. Good luck with your investing.

Be the first to comment