Maks_Lab/iStock via Getty Images

Input/Output

Dear Partners,

Since I last wrote to you, our absolute performance has improved. Net of management fees, we are down roughly 6% year-to-date, although our relative outperformance to the market has narrowed to de minimis levels (our benchmark is down about 7%). The clients-only portfolio commentary includes an extremely detailed review of each position, as per usual.

From a high level, earnings reports of both our companies and their peers/competitors have largely left us very optimistic about the prospects of our portfolio companies. Whatever economic circumstances may or may not transpire, we believe that our portfolio is well-equipped to deal with them.

While the future is of course unpredictable, it is clear that at least as of right now, from the forward-looking statements of our portfolio companies, there is absolutely no basis whatsoever for the extreme doom and gloom that was prevalent when we last wrote to you, at least when it comes to our companies and the industries they operate in.

We think that the overwhelming majority of our companies remain substantially and unfairly undervalued, even relative to “reasonable” levels of undervaluation and relative to the typical value spread we have seen in our portfolio since inception.

For example, we have four portfolio companies comprising 23% of AUM – all in different industries, with different fundamental drivers -currently trading at or near levels they traded at in March/April 2020, despite the fact that business prospects today are obviously far superior than they were during the height of COVID-related uncertainty.

Similarly, one of our larger positions hovers around 52-week lows even after announcing a home-run acquisition that we believe increases their fair value by 30% or more of their current market cap.

As such, we think our portfolio is more attractive than it has been in most environments since inception other than COVID. This is not something we say often, nor is it something we say without data (see the private portfolio commentary).

Similar to how we felt in August 2020, the prices just don’t even come close to reflecting the fundamentals, even with some allowance for potential economic degradation. We believe that many of our holdings are increasingly “coiled springs” – or what Don Yacktman once called “beach balls held underwater.”

The balance of this letter discusses our evolving thoughts on portfolio management. We believe our new approach has already begun to benefit us and will continue to be additive to our process over time.

Nuclear Winter

I was a young boy that had big plans

Now I’m just another [cranky] old man

[…]

Wasted youth and a fistful of ideals

I had a young and optimistic point of view

– “The Grouch,” Green Day

I’ve recently been talking to three or four analyst friends who are either actively starting, or thinking about starting, their own firms, which would all have directionally similar strategies to ours (small-cap long-only value with a focus on fundamental research).

Most of these friends are probably better analysts than I am, so my advice has been heavily skewed towards the only area where I feel like I have something to offer – namely, my experiences as a portfolio manager. This has led me to reflect on what we’ve done well and what we haven’t, and where we’re increasingly focusing our efforts.

This has changed me from who I was when I started the firm. I jokingly once referred to an older mentor of mine as “Nuclear Winter” because he walked around seeing and thinking about all the bad things that could ever happen. He told me that that’s just what a decade or two in the business of investing does to you, and while I don’t have as many gray hairs as he does, I have more than I should for my age. So I kind of get it now.

One of the hardest things in life (not just in investing) is to accept that the world is the way it is rather than the way we think it should be. We can deny and fight against reality as much as we like, but ultimately it governs our outcomes.

The title of this letter, Input/Output, refers to this quandary. Too often we focus on optimizing our inputs rather than recognizing that external factors often govern the relationship between our inputs (what we can control) and the outputs thereof (which we cannot directly control).

This is where I think portfolio management differs from analysis. Portfolio management is the intermediary between the input of the investment process (good ideas and research) and the output (long-term returns).

With all due respect to the research process (which we value very highly), I’ve seen many instances of people with great individual ideas and very thoughtful analysis who nonetheless end up with bad results due to portfolio construction decisions. I’ve seen this on both ends of the spectrum – people who were far too conservative (refusing to buy objectively cheap stocks for non-fundamental reasons, such as macro) to people who were far too aggressive (being too willing to hold onto extremely overpriced stocks for non-fundamental reasons, such as tax considerations).

To be clear, we are not simply throwing peanuts from the cheap seats. Similar outcomes could have happened to us. In an alternative counterfactual universe, during COVID, we could have suffered severe permanent impairments of capital if the world had broken a different way. We count ourselves lucky and fortunate that we did not. In this actual universe, we didn’t do nearly as well as we could have. We’re very focused on ensuring that we don’t make the same mistakes twice.

A corollary to this is that my biggest regrets tend to be portfolio management decisions rather than analytical ones. While I could have been a better analyst (and continue to strive to be), I think maximizing my skills there would have had limited impact – because the bottleneck is portfolio management.

Therefore, this is the area where we are striving to improve the most, optimizing for maximizing our returns and minimizing our risk in the real world – not in a theoretical world that we wished existed.

Below are some thoughts in terms of how I now see the world from a portfolio-management lens rather than an analytical one, and things we think we got wrong initially. They all kind of blend together so there will be some repetition, but we’ve tried to organize this discussion so that each point conceptually builds on a previous one.

To be clear, we are firmly value investors and always will be; I don’t think anyone can in good faith accuse us of investing in lots of high-flying companies “at any price” (we’re much more likely to go dumpster diving).

But we don’t feel the need to be constrained by what we “should” do or say as value investors, and indeed much of what we’re going to say below sounds very un-value-y. My job, ultimately, is not to pass some theoretical value investor purity test. My job is to buy stocks that go up and make money for the people and organizations who have entrusted their capital to me.

I happen to think that a fundamental value investing orientation is the best, safest, and most probable way to accomplish that goal. Everything we do is grounded in this approach. But between input and output, our portfolio management approach can make a big difference. We’re not talking about not being value investors – we’re talking about layering real-world trading sensibilities on top of value investing principles to ensure that the quality of our output reflects the quality of our input, the latter of which we are very proud of and confident in.

Lesson 1: I was wrong to believe that public-markets investing is like private-markets investing.

If you read the value investing literature, a common theme is that value investors often espouse the belief that one should make decisions in the public market as if you were purchasing a private business – “don’t own a stock for a day if you wouldn’t be comfortable owning it if the market shut down for ten years,” etc.

Owning an illiquid, hard-to-sell private business – that you might have to own for a long time, or forever, with significant frictional costs around selling – is very different than buying a relatively liquid public stock that you can sell tomorrow with a single click.

While the “private owner” mentality is certainly a more sensible starting point than the “gambling in a casino” starting point espoused by many retail investors, it seems to leave several pieces out of the puzzle. If I

hypothetically wanted to buy one of our portfolio companies in full, I wouldn’t really have an option to sell part of it for a big gain in a year, then potentially buy back that stake two years later for less than I originally paid for it.

But those are things we can (and have) done with our positions; indeed, there are many situations we can name over the years (Fogo de Chao, Sprouts, AerCap, Franklin Covey, MiX Telematics – the list goes on and on) where we have bought a stock, sold it for a substantial profit, and subsequently had an opportunity to repurchase the stock at the same price we did the first time, or sometimes even a better one.

The major factors differentiating public markets from private markets are

A) relatively frictionless liquidity, and,

B) continuously quoted prices.

As such, long-term fundamentally-oriented value investing is not incompatible with relatively short-term trading to take advantage of B).

Indeed, we would argue that Berkshire’s decision not to sell all of its Coca-Cola shares in the late 90s at egregiously overvalued prices is one of the single worst – and easiest-to-avoid – mistakes that Warren Buffett has ever made, particularly given the plethora of attractive opportunities available at the time in other companies that were left for dead in the “new world” tech market.

It won’t escape readers’ attention that we have – at least on one level – always espoused this philosophy; indeed, a question we used to get from prospective clients is why our turnover was so high relative to most value-oriented funds. We’ve always espoused actively buying and selling our positions based on their valuations. But there are multiple layers to understanding this theme, which we will continue with…

Lesson 2: I was wrong to assume cheapness or valuation drive or protect short-term returns.

This may sound contradictory to what I said above, so let’s start with the reconciling nuance. At the macro level, notwithstanding some of the idiosyncratic abnormalities of the past decade, we absolutely think that returns over a, say, 2-3 year timeframe are likely to be better for egregiously undervalued stocks rather than egregiously overvalued ones.

Generally speaking, if you observe two businesses with similar underlying characteristics and one trades at 24x EBITDA while the other trades at 6x EBITDA, we think they’re likely to end up with very different return profiles three to five years later – perhaps both converge to 12x EBITDA, resulting in massive losses (or flat results at best) for the former company, with stellar results for the latter company.

However, when we restrict our sample size to companies that we already think are undervalued – and the question is the comparatively minor relative difference in cheapness (i.e., one stock that we think is 25% less than fair value compared to another stock that is 35-40% less than fair value) – we think the predictive ability of valuation is much less, at least over short to medium term (say 6 to 18 month) timeframes.

For one thing, we originally believed that owning high-quality companies with good balance sheets at inexpensive valuations would protect us during market downturns.

Instead, almost exactly the opposite has happened. There are many occasions on which we’ve seen high-quality companies with cash balances trade down more than lower-quality companies with large amounts of debt. Again, note that if it weren’t for the buyout of Menzies, we would be meaningfully lagging the market year-to-date.

In the short-to-medium term, we think stocks are largely driven by sentiment. Furthermore, after nearly seven years of full-time professional small-cap investing, we’ve found that this short-term sentiment is impossible to predict. We’ve seen stocks sell off 10-20%+ on the day of earnings we thought were very strong. We’ve seen stocks rally 1020%+ on the day of earnings we thought were very weak. We’ve seen oil stocks fall by 50% during periods during which oil prices rose substantially. We’ve seen unbelievably cheap stocks trade down to almost net-net level; we’ve seen unbelievably expensive stocks trade up to valuations that are almost impossible to justify no matter how aggressive your model.

Lesson 3: I was wrong to over-rely on our internally modeled valuations.

There is a close corollary to the above. As you are likely aware, we have spreadsheets tracking the prices of stocks in our portfolio and on our watchlist, as compared to our estimates of their fair value. This is a very useful tool for highlighting which stocks we might want to buy (or sell) on any given day. A real section of the spreadsheet is pasted below. (Note that this includes many companies which we haven’t looked at in a long time, or have “placeholder” fair values for, so please don’t interpret this as a fully up-to-date

We try to use a consistent valuation methodology for all companies we look at. Of course, we’re only human, and undoubtedly sometimes we will be overly aggressive or conservative.

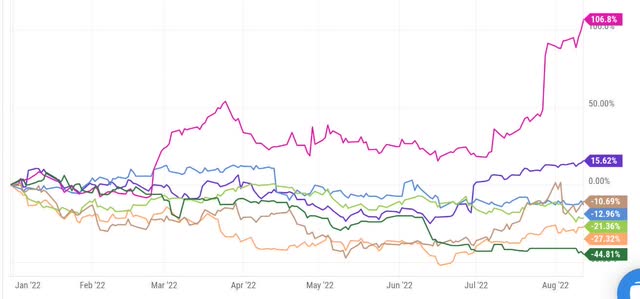

Now, let’s look at the YTD performance of all stocks that are currently in our portfolio. There are two charts because all 15 stocks wouldn’t fit on one chart in a readable way. (Note that we did not own all of these at the start of the year; we’ve intentionally excluded the individual names because it’s the idea and not the names that are important.)

Clearly there is significant dispersion. Crucially, though, we don’t see any correlation between YTD performance and how cheap we thought things were at the start of the year. In fact, excluding the one huge outlier (which unfortunately was only a tiny position for us until July), several of the stocks we thought were the cheapest in February-March have been middle of the pack or even some of the biggest decliners since then. Conversely, several of the stocks we thought were (relatively) the least cheap have actually been much better performers.

Similarly, we don’t even see a strong correlation with fundamental performance. Some of the biggest losers have been weak fundamental performers, to be sure. Similarly, the two biggest winners have been very strong fundamental performers. But in that large bucket of stocks that’s down 15 – 40% YTD, we don’t really see any good reasons why certain stocks have recovered from the June lows, while others largely haven’t (and in some cases have even declined further).

Two of the worst-performing stocks reported what we thought were very strong results; conversely, the outlook for one of the better stocks in the chart is substantially worse today than it was in April, while the price is now higher. Putting all of this together, we think that oft-mentioned “catalysts” don’t really exist, at least not over short-term time periods – we’ve simply far too often seen stocks collapse after great, far-better-than-expected earnings reports or acquisitions (or vice versa).

This knowledge isn’t exactly new, but is something I’ve internalized further. We still think it makes sense – of course – to sell companies that are close to fair value to buy companies that are deeply, deeply discounted. However, again, we’re talking about a question of degree. And that leads us to…

Lesson 4: I was wrong about momentum.

“Tell me one last thing,” said Harry. “Is this real? Or has this been happening inside my head?”

Dumbledore beamed at him. “Of course it is happening inside your head, Harry. But why on earth should that mean that it is not real?”

– Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows by J.K. Rowling

One frequent – and realistic – criticism of finance types is that they try to reduce everything to a spreadsheet. The real world isn’t a spreadsheet. One anecdote we’re fond of citing is that of a portfolio company that introduced a highly engineered, differentiated product that saved its customers lots of money. On a spreadsheet, everyone in their industry should have adopted this product overnight.

In practice, there was someone within the purchasing department of customer organizations whose job – under threat of being fired – was to source components at the lowest possible price. This means that he is supposed to seek reductions of 20-30% on those components, not increases.

Mr. Purchasing Manager, therefore, had no interest in paying a 20-30% premium for this new product even though it would deliver an ROI substantially in excess of its price. The “silo” in which Mr. Purchasing Manager operates can’t be modeled on any spreadsheet and doesn’t physically exist in the world. But, as Dumbledore said – why on earth should that mean it isn’t real?

Momentum is a real phenomenon in both business fundamentals and market sentiment, because things don’t generally change overnight in the real world. There are certainly exceptions – today’s hot fashion trend might be right out by next spring. Generally, however, people’s behavior (which applies to organizations writ large) tends to be somewhat sticky.

There are two important applications of this. The first relates to business fundamentals. Companies that are doing well tend to keep doing well in the short to medium term. This is perhaps even more true in reverse; we’ve found that turnarounds and cyclical recovery stories generally tend to take twice as long and cost twice as much as we modeled.

COVID recovery plays are a great example of this. We dramatically overinvested in various types of COVID recovery plays – mostly travel-related, although some others such as energy-levered industrials as well. We thought that particularly after effective vaccines became widespread, the world would “snap back” to normal.

Instead, recovery has been mixed and choppy. In no particular order:

- Many consumers took longer than we expected to return to pre-COVID habits – they have largely fully done so now, but it’s a full year after what we thought were reasonable expectations.

- Some governments, particularly in Asia, have stuck with the same policies they had in early 2020.

- Companies that were forced to cut prices or offer incentives to customers during COVID have “taken the elevator down and the staircase up” on the margin front – while they continue to recover to pre-COVID levels, even now that issue 1) is no longer a problem, their customers are reluctant to simply accept price increases in line with inflation, at least over the short term.

This is merely the easiest tangible/concrete example to demonstrate that we have underweighted fundamental momentum – to our detriment – in our fundamental analysis. Our recovery plays largely worked out as a whole, but so did many more cyclically-independent companies (or at least companies that were affected by COVID in different ways.) In hindsight, we could have achieved the same or better returns without the same level of risk and frustration.

The second – which compounds, and is related to, the above – relates to stock price performance. This is probably where I’m going to lose a lot of hardcore value investors, but I’ve learned over time that sometimes I should care about how stocks “behave” in addition to what they’re worth (yes, I can see you shuddering already). And we should incorporate those learnings and patterns – like everything else – into our investment process.

To be absolutely crystal clear, I am not saying that we will buy or continue to hold stocks because they have been going up, and think they will continue to go up, in the absence of a value thesis.

It’s actually the opposite. I think we will be more cautious about buying or holding stocks despite a credible value thesis, as we recognize that other factors (rather than just value) matter.

This isn’t to say that we will not buy stocks because “they might go down more.” That’s exactly how we’ve earned most of our returns! We are often the buyer of stocks when few other investors want to buy; many of our very successful ideas (such as Franklin Covey, Fogo de Chao, and Sprouts) have been ones that were very difficult to convince other investors of. Abandoning this approach would doom our investment strategy. It does, however, change how much we want to buy of a stock – we will return to this idea in the next section.

For now, in terms of taking “stock behavior” into account, I’ll provide one tangible example that is no longer in our portfolio largely for this reasons – AerCap (AER). We initially invested in AerCap due to its historical business stability and very steady compounding of book value per share, driven by the capital allocation prowess of CEO Aengus Kelly.

Excluding transaction accounting related to the GECAS acquisition combined with recent markdowns due to expropriation of the company’s Russian assets (which we expect will eventually be recovered, at least in part, from insurance coverage), the company’s book value per share would have compounded at at least a 9% annual rate since the start of 2016, despite COVID.

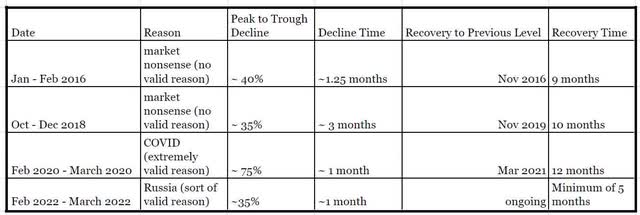

But the stock price today is only up a paltry 12% total over that time period. This is primarily due to AerCap’s unfortunate habit of selling off viciously anytime there is macro threat – whether real or (more often) perceived. And while sentiment is quick to bail, it’s slow to recover. As shown in the chart below, there are four separate 35%+ drawdowns that AerCap has gone through since the start of 2016. All but one drawdown took no more than 5 weeks (one took about three months). In each case, it took the better part of a year for the stock to recover to previous levels.

We’d seen this story enough times to get wise. When Russia started to hit the headlines in February 2022, we liquidated the remainder of our position in AerCap even though we thought fundamental value remained – and fortunately sidestepped the last drawdown in the chart above, from which the stock has still not recovered (although subsequent weakness is due, we think, more to general market blahs than to anything AerCap-specific.)

This isn’t to say we’d never own AerCap again; we still like the company and its management team and would be willing to own it at the right price. But whatever the risk-reward of AerCap as a business might be, its risk-reward as a stock is often asymmetric in the wrong direction – the stock very rarely violently rallies (and its upside when it does is typically capped, as this is not the sort of business that is ever going to achieve a stratospheric multiple). Conversely, if you own AerCap for long enough, you’re going to get punched in the mouth multiple times.

So we would be more amenable to buying AerCap only after such a selloff, and not continue to own it when it trades at what we view as a reasonable – but not extreme – discount to its fair value, since earning the last 20% seems to be a lot less likely than taking a fundamentally unjustified 20-30% hit.

This is not a conclusion we would ever come to through any level of fundamental business analysis. In fact, we think that the company’s relatively strong performance through a variety of real (rather than perceived) crises just underlines the quality of the business, and we think the stock price today represents a significant discount from fair value. But as good a business as AerCap may be, its stock has characteristics that we’re less comfortable with – so we prefer owning other businesses that have similar discounts, or even slightly lower discounts, that we think are likely to work out better for us.

Lesson 5: I was wrong about concentration.

This is the big point that I’ve been building up to.

To start with, I think it’s generally uncontroversial to assert that it’s much harder to generate differentiated performance as a value investor with a highly diversified portfolio. People’s definitions may differ, and we won’t really speak for what works for other people, but for us as a one-man shop, we think that owning 30 stocks (let alone more) would be difficult. This seems to be the case even for shops with several analysts, as there is only so much time in the day to keep up with existing positions while conducting due diligence on new ones.

But we think there is dose-dependency to concentration; this is kind of what we’ve been saying the whole letter. Too much of a good thing can have negative side effects. One or two extra-strength acetaminophen will help with a headache; seven or eight on an empty stomach and/or in combination with alcohol or other substances might literally permanently destroy your liver.

The smart-sounding idea that leads a lot of investors (including my younger self) towards overwhelming concentration – which I’ll define as a portfolio with, say, fewer than 10 names, or many double-digit exposures or a 20%+ exposure – is that some ideas are multiples better than others. If you can identify a few such ideas, why would you want to “diworsify” by taking capital away from your best (or second, or third) idea, and allocating it to ideas 8 through 12?

This analysis presupposes that one can ex-ante, with high conviction, identify ahead of time what their “best idea” is at any given idea in time. We no longer believe we can do this.

Our overall track record since inception, as well as the number of names where we have made successful investments that played out for the reasons that our analysis suggested they would, means it’s reasonable to assume that we have investment skill. As part of that investment skill, we do think that we can accurately rank fundamental risk-rewards. Some stocks are significantly cheaper than others; some stocks have significantly lower fundamental risks.

But as we discussed, cheapness – and fundamental risk – don’t always seem to drive stocks over short periods of time. Earlier, I mentioned our watchlist spreadsheet – it’s just a tool. Unfortunately, I used to treat it more like a religion – which is what led, in part, to the overconcentration previously discussed.

If my spreadsheet said stock A was trading at an expected 3-year return of 20%, and stock B was trading at an expected 3-year return of 30-40%, I would pretty much sell all the A and buy all the B. And it didn’t always work out the way we thought it should.

So the question of whether we can ex ante figure out what our best idea is – insofar as, which of our ideas, regardless of risk-reward, will perform the best over, say, the next 6 or 18 months – there, we have a much more mixed track record.

Despite our favorable base rate for successful investments in general, we can identify at least two stocks that were our largest positions that subsequently had very poor results (both fundamentally and in the public markets) over the ensuing several years. To be clear, I haven’t reviewed trading records as part of this analysis – but from memory, this means that we ex post regret making two of our three biggest ideas our biggest idea. That’s not a very good hit rate for “biggest idea,” which has often been a 15%+ type position that should essentially never fail and always work out to justify that level of position sizing.

Of course, this is a small sample. But far more often, we had high-conviction, lower-risk, higher-return positions that were in the top few exposures, which ended up being significant underperformers (relative to the rest of our portfolio) over a year or two, even if they caught up or pulled ahead by the end.

This even applies to our investment in Franklin Covey (FC) – which has been a massive success over the long-term but wasn’t necessarily the best performer in every environment, or even necessarily the best performer in our investment universe that we understood well. This suggests, to us, that making it a 20-30%+ position at times was unjustified given the substantial incremental risks associated with such a position size.

In other words, to justify making one position 2, 3, or 4x as big as our typical “core” position size, we think it should either have 2, 3, or 4x the returns, or generate similar returns with incredibly low risk (think, like, a business that sells toilet paper or extremely sticky enterprise software – something that would never have not worked out in any counterfactual universe.)

Ideas that are really that much better are extremely uncommon, and as we’ve discussed, our ability to identify them ex ante has been poor.

There are, of course, certainly time periods where the opposite happened, and one really big position did really well and pulled up our whole portfolio performance – but if we got to “do over” our portfolio from inception, we think we would have, on the whole, done much better with a less concentrated portfolio.

Indeed, one of our clients who is skilled in such analysis actually looked at this for us before investing, and they found that while our performance vs. position size did have a positive slope (i.e. bigger positions did better on average), it was not a very strong slope.

So even relative to our initial conclusions post-COVID that we needed to be more diversified, we have been taking this approach even more seriously. Today, we own 15 positions above 300 bps with no single exposure larger than 12% and the next largest exposure below 10% – and we think this likely represents the median to high end of our concentration (say the 60th to 70th percentile) in the longer term.

Our research process continues to generate a substantial volume of ideas (including both long-followed names from our watchlist, and new ideas) and many of our existing portfolio companies could absorb substantial incremental capital if it became available – not to mention several additional names we could confidently invest in today, and plenty more that we could likely invest in after some additional confirmatory due diligence.

We feel comfortable in being able to keep up with the current portfolio size and having operated in this environment for a little bit, continue to believe that the target of 12 – 17 stocks we discussed two quarters ago makes sense as our long-term target.

Obviously we haven’t sold down existing larger positions at unfavorable valuations, but we’re moving more towards having most positions be in a tighter size bracket.

The primary benefit of lower concentration (i.e. lower risk) is fairly obvious and doesn’t bear discussion. However, there are several additional benefits that we think are less well-understood, insofar as we believe that reducing concentration (from the levels where we previously ran) is the proverbial “free lunch” – if we’re right, it should both boost our returns and reduce our risk.

There are two mechanisms here. The first is internal optionality; i.e. the ability to purchase more shares of the company in question at a more attractive valuation. In most instances, when we buy a stock, it doesn’t immediately go up and to the right. It usually goes up a bit, stays flat, or (seemingly most often) declines further from where we bought it. Given that we traffic in misunderstood and undervalued securities, we’re usually not going to pick the bottom before the market suddenly appreciates and fully values it.

Further to this, we typically (again, not always) add to positions if their prices decline if we still believe in the fundamentals (which is the case the vast majority of the time.) As such, our historical returns could actually be theoretically separated into two different types of purchases – our initial or “early” purchases of shares, and our subsequent or “late” purchases of shares. Returns on the first category would be fine – good, but not great. But returns on the second category would be spectacular (usual disclaimers apply – again, we’re not actually analyzing data here; just providing our qualitative impressions.)

The problem with going big on positions fairly early (even if we’re very knowledgeable about them and confident about them) is that we’ve expended all our ammo in the first round of the fight – leaving us no chance to reload on the stock if it gets even more attractive. Indeed, many of our most attractive ideas have seen 20-30% or even greater drawdowns along the way to solid returns from our initial purchase price.

The second mechanism, external optionality, is the one we’ve probably discussed more before, so we’ll keep it brief. Having overly large positions in individual names can prevent us from taking advantage of other opportunities if they come up. COVID is a great example of this, where there were plenty of attractive securities, but it didn’t really make sense to sell our holdings at values down 30, 40, or 50% to buy the other ones. Having more shots on goal would have given us options to monetize securities that traded at smaller discounts to fair value.

To sum up, the beliefs driving our evolved portfolio management philosophy are that:

- Short to medium-term (months to a year or 18 months) stock prices are relatively unpredictable.

- Our investments generally do well over our multi-year investment horizon.

- Our largest investments have performed somewhat better but not disproportionately well over either short or longer-term time horizons.

- The cheapest stocks don’t necessarily perform better in the short-term.

The net result is that – again, with the underlying grounding of starting from a value-oriented fundamental investment philosophy – we should be somewhat more humble about realizing that our best idea isn’t necessarily the idea we think is the best, and spread our bets a little bit more to take advantage of both our internal base rate, and the base rate of the market presenting really good opportunities fairly frequently (that we can only take advantage of if we aren’t sized up already.)

Conclusion

We are grateful for our clients’ support over the past several years, which have been extremely challenging as the world has careened from one crisis to another. As a result of incremental contributions from existing clients, our AUM has grown to $70 million, and assuming flat market performance, we would expect it to reach a figure in the low $80 million range over the next year or two depending on when clients choose to utilize their capacity commitments. At that point, we would not anticipate any further material inflows to our AUM, and our future capital base would be entirely market-driven.

As a reminder, existing individual-investor clients are welcome to add small amounts of capital at their discretion, but we remain closed to new clients so that we can focus our efforts on compounding capital for existing clients.

We look forward to updating you further next quarter.

Westward on,

Samir

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment