imaginima

Arhaus, Inc. (NASDAQ:ARHS) is a retailer of luxury furniture and décor. Operating since 1986, the company now has 80 showrooms in the US, and went public in November 2021.

The scarce financial information available, going only as far as 2019, shows significant growth and interesting business economics. The company continues delivering on this promise as of 1H22. Arhaus is also free of financial debt and has good cash conversion.

Arhaus is currently priced at an expected 2022 PE of 13, a relatively low PE for a profitable, debt-free growth story. The reason might be the business exposure to economic cycles, particularly those affecting high income families. Investors probably fear Arhaus is not going to grow but shrink, and that its showroom fixed structure is going to become a drag on profitability. Another risk factor is the substantial shareholding of the company’s founder, who may need to drop some of that holding on the market.

We will explore these concerns, and evaluate negative scenarios. I believe the business characteristics justify the current prices, with the company being fairly valued. However, the reader should understand that the risks are very high and that a long-term investor has almost no margin of safety.

Note: Unless otherwise stated, all information has been obtained from ARHS’s filings with the SEC.

Luxury furniture industry

Arhaus sells luxury or high-quality furniture. According to the company’s investor presentation, this can be broadly defined as furniture that is above the average in pricing and quality. Let’s analyze Arhaus’s industry characteristics and competitive position.

Fragmentation

According to Arhaus, the industry is highly fragmented, with their biggest competitor holding only 6% of the market, while Arhaus holds 2% of it. Fragmentation has its positives and negatives. On the positive side, the industry does not have a cost or differentiation leader that can define the market dynamics. On the negative side, fragmentation means competition and excessive optionality for the customer.

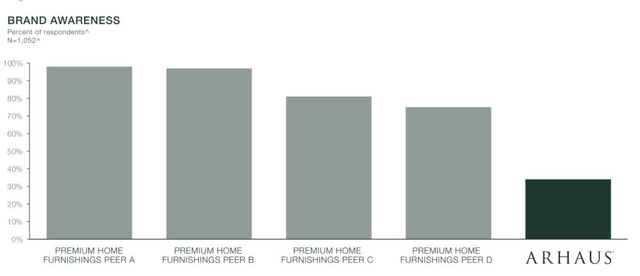

Arhaus is not particularly well known. I ran a google search on ‘best luxury furniture brands’ and ‘best high quality furniture brands’ and Arhaus was mentioned in 30% of the sites. This is consistent with the information presented below, also from the investor presentation.

Arhaus brand awareness compared to competitors (ARHS’ investor presentation, March 2022)

Moat building possibilities

In terms of ability to develop a moat, the luxury furniture industry is quite good.

To begin with, Arhaus sells directly to consumers, which is better than selling to businesses, ceteris paribus. Businesses tend to develop systems to compare competitors on a rational basis.

A second benefit for the industry is that customers do not have a clear set of metrics to differentiate the offer. How does a regular customer compare two luxury chairs or two luxury sofas? He may perceive that one is better than the other, but he is not going to inspect the porosity of the textile, wood hardness, material durability, etc.

In customer perception rather than measurable characteristics lies the moat. Good marketing, brand building and retail experience can convince the customer on a basis completely different to what drives business costs.

Arhaus knows this, and acts accordingly. The company has big 16 thousand square feet showrooms that can comfortably accommodate different furniture settings. Most of their stores provide interior designer services, which I guess are free (the company does not clarify this). According to the company, designer generated orders are 3 times those generated by other salespeople. The company also mentions a high correlation between product advertising in catalogs and digital media to product revenue. That is, Arhaus knows the moat is as much the product as the purchase experience and that it can direct consumer desires.

Compare that to someone surfing websites to find the perfect car for his price segment, or a purchase manager developing rational metrics to evaluate a supplier’s offer. That is lack of moat, that is competing on the product characteristics.

Vendors and supply

In terms of vendors, Arhaus also has the upper hand. The company does have its own manufacturing facility in Ohio, but that only represents 12% of 2021 revenue, according to the investor presentation. The remaining is sourced from furniture factories or from smaller artisans. According to the company’s 10-K for FY21, 60% of the company’s revenue was generated by products sourced abroad.

The relation between Arhaus and its vendors is of mutual necessity, but the balance is weighted towards Arhaus. True, it is not full of luxury furniture artisans and factories in a totally commoditized industry like lower quality furniture, this is a point for manufacturers. But Arhaus has access to retail demand in the biggest, most affluent market in the world. The company can offer good volumes that would be difficult if not impossible for the manufacturer alone.

In my opinion, Arhaus is not competing directly with its vendors to extract value but rather with other retailers that want to access the same product sources and are willing to overpay. The company does not mention signing any exclusivity agreement, only that it builds strategic partnerships with some of its vendors. It does mention that 95% of its products can only be purchased with them, and nowhere else.

Using vendors has an advantage against manufacturing that is not cost related, which is avoiding hubris and promoting competition. Arhaus’s team of designers is 20 people alone. They do not design the company’s products, it would not be possible. They only choose from an ecosystem formed by many small producers that compete with each other. Vendors are never safe, they have to improve constantly. The manufacturers spend money and time in designing to compete, and Arhaus grabs a significant portion of that value by controlling the demand source. It would be much more difficult to achieve the same dynamics with in-house groups of designers. Therefore, I would not like to see Arhaus in-house manufacturing growing in the future.

Store leasing

Arhaus also needs to supply itself with stores. These are big stores, averaging 16 thousand square feet. It is not the biggest (the average Walmart (WMT) has 180 thousand square feet) but is higher than the average of 10 thousand feet for US retail, according to Nielsen. The most distinctive characteristic of Arhaus is that its stores have to be placed in relatively premium locations, to enhance the company’s premium branding. This means it has to pay for those locations accordingly. With the supply being fixed in the short-term, the dynamics of retail space are governed by demand. If an area has extra demand, it will have extra high prices across the board. Of course that extra demand probably comes from extra customer traffic or some other desirable characteristic. Arhaus has to strike a balance, I guess.

Arhaus’s lease cost stands at about $50 million yearly according to their 2Q22 10-Q report. This includes their deposits and manufacturing facility, but the composition is not disclosed. Considering 80 stores with an average of 16.3 thousand square feet, the square feet rent comes at about $38 a year.

I have found that Statista lists about $25 as the average shopping rent per square foot, while Solo lists prices ranging between $10 and $25, depending on location.

That means Arhaus’s renting costs are relatively high. However, Arhaus includes a percentage of sales rent on its lease costs, which may have not been included by Statista and Solo (I am not sure) that are normal in premium locations.

Industry cyclicality

A final point is the industry’s exposure to business cycles. According to Arhaus, the company is exposed particularly to business cycles that affect the consumption capacity of high-income families.

In particular, Arhaus comments that movements in interest rates, second and third home purchases, availability of home equity loans and wealth effects from the stock market have a correlation with their sales.

This might be one of the reasons the stock market is pricing Arhaus relatively cheaply compared to its growth history. We have seen a year with increasing interest rates and falling stock prices, both of which should negatively affect Arhaus’s customers. This has not been felt yet, at least from data up to 1H22, more on this later.

A problem with falling revenues is operating leverage, from fixed lease and labor costs. This can greatly affect operating and net income. A second order effect is that a prolonged reduction in demand can lead Arhaus to close stores, which in turn leads to significant restructuring costs. These come from lease cancelation penalties and employee severance payments.

One possible solution for this kind of cyclicality is considering opening stores outside of the US, and particularly in relatively affluent emerging markets that may be uncorrelated with economic conditions in the US. It is not a perfect solution, given that it carries additional managerial costs and that no market is perfectly uncorrelated or negatively correlated to the US.

Arhaus’s operations in detail

I have commented on many aspects of Arhaus’s operations in the previous section, but in this section, I will delve into some of them in particular and provide financial calculations.

A new public company

Arhaus went public in November 2021. That means the company is still adapting to the reporting requirements of public markets. This deficit comes up in several aspects of my analysis.

Arhaus was considered an emerging growth company, meaning reduced reporting requirements. However, given that its market cap has been above the $700 million threshold, it will lose this condition and will become an accelerated filer with the SEC. Hopefully this will mean better reporting in the future.

The company also recognizes on its latest 10-K that it has found and is in the process of solving several financial control and reporting deficiencies. The company has received an unqualified review from its auditor, PricewaterhouseCoopers, but should remediate these deficiencies in this fiscal year.

Another deficiency is the late adoption of updated lease accounting standards, only in the last two quarters, when it became mandatory. Most companies have adopted the new standards one or two years ago. That means that comparable lease information is only available on an unaudited, less commented quarterly basis.

Arhaus could also improve the reporting detail of its expenses. The company does not disclose the nature of its gross and operational expenses on a separate section, something that is quite common for many companies, particularly of Arhaus’s size. It also lacks detailed inventory reporting.

The company does report where it allocates lease costs, and the method used is unusual. Normally, store lease costs go into SG&A, but Arhaus allocates most store lease costs in cost of goods sold. This has two effects. First, it underestimates Arhaus’s gross margin, and consequently its bargaining power with furniture suppliers. Second, it may lead investors and analysts to believe that a greater portion of costs are variable than they really are. Usually CoGS is considered more variable and SG&A more fixed. I provide adjustments for this peculiarity later in this section.

Financial strength and cash flow cycle

A positive aspect of Arhaus is its total lack of financial debt. The company had an expensive term loan before going public, but it canceled that debt with the share issuance proceeds.

As of 1H22, Arhaus has an open $50 million credit facility paying the Bloomberg short term bank yield plus 1.5%. However, the company has not drawn funds from this facility. This signals two other positive aspects.

First, Arhaus has not jumped into an investing frenzy to open a lot of stores using debt in 2022. This proves management is somewhat wary of unstable economic conditions in the US. It is true however that leases can be considered a form of debt, given that they carry cancellation costs and increase operational leverage.

Second, Arhaus has an interesting cash flow cycle that allows it to finance freely some of the working capital required to fuel growth. Usually a company that is growing has to obtain funds to finance working capital. However, Arhaus receives 50% of a product’s price as a customer deposit prior to delivery. Considering that Arhaus unadjusted gross margin is close to 40%, that means the client is financing Arhaus’s inventories. In fact customer deposits match inventories quite closely. Of course, Arhaus also needs to finance other working capital like the inventory that will not be sold but exposed on the stores, or credit provided to small vendors.

Arhaus also needs to finance capital expenditures, like store remodeling, and the expansion of its manufacturing and distribution facilities. As of 1H22, the company has spent $13 million in CAPEX, net of landlord contributions (the gross figure is $20 million). According to Arhaus, CAPEX is higher than it should be long term because the company is expanding its core manufacturing and distribution facility in Ohio and is opening two other distribution centers, in North Carolina and in Texas. When we talk about net income later, the CAPEX figure will seem small in comparison.

Fixed and variable costs, operational leverage

Given that Arhaus does not disclose the details of its gross or operational expenses, it is difficult to come to firm conclusions regarding how much of its cost structure is fixed.

As a proxy for more detailed information, we can consider that SG&A costs are fixed, while CoGS is variable. This is not perfect, of course. Some SG&A costs might be variable, like salesmen bonuses based on revenue. Some CoGS might be fixed, like a deposit’s lease cost.

First, we need to move some lease payments from CoGS towards SG&A. Arhaus considers most store lease costs as part of CoGS, but I prefer to consider them SG&A. There are two reasons for this. First, the usual is to consider store rent costs as part of SG&A. Second, lease costs are fixed or at least semi-fixed in the medium term, meaning they more naturally fit SG&A.

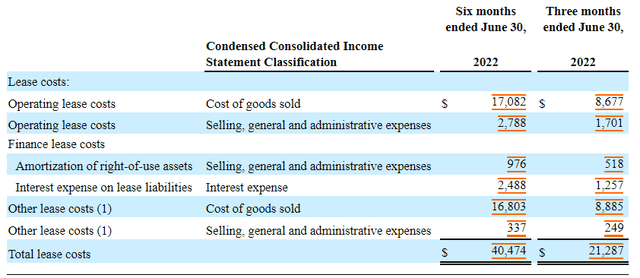

On its 2Q22 10-Q report, Arhaus provides a table with the position of each lease component on its financial statements. The reader may notice that lease costs come to $40 million for 1H22, while we considered $50 million for the whole year. The difference arises from short-term lease costs, of $17 million, that are not considered part of store rent. Removing them yields close to $27 million, in line with our yearly figure.

Arhaus lease cost allocation (Arhaus 2Q22 10-Q report filed with the SEC)

In my opinion, the short-term lease costs should remain in CoGS, as we have no information to allocate them in SG&A. However, the $17 million from operating leases that is allocated to CoGS should be moved to SG&A.

Restating 1H22 income statement figures, we find $305 million for CoGS, from $322 million, and $175 million for SG&A, from $158 million. That yields an adjusted gross margin of about 45% for 1H22, totaling $247 million.

Share structure, controlling shareholders, and management compensation

Arhaus has a strong controlling shareholder, the company’s Founder, Chairman and CEO, John Reed. According to the company’s proxy statement, Mr. Reed directly controls 32% of the company’s stock capital. Family trusts own a remaining 30%.

This is not all. Arhaus has a double class share structure. Class A shares are entitled to 1 vote. These are the shares traded in public markets. Class B shares are entitled to 10 votes. Economically, both classes are equal, but Mr. Reed and the family trusts control all class B shares. Therefore, they have a 94% combined voting power.

Personally, I do not find having a strong controlling shareholder something negative. Quite the contrary, as long as the strong shareholder is honest and does not damage minority shareholders, then it can be beneficial to have someone with a lot of skin in the game.

Another early investor fund called Freeman Spogli owns 21% of the capital stock through class A shares. That leaves only 17% of the stock as float.

This does represent a significant risk. The problem is not that the float is low and therefore volume is thin, but rather that if any of the founder investors wants an exit, it will have to sell new shares to the market, depressing prices.

This has not occurred yet. According to Nasdaq, both insiders and institutions have increased their holdings in the past 3 months. However, it may happen soon, given that early investors were banned from trading stock in the first 6 months after the IPO in November.

Finally, in the issue of management compensation, I think the company could improve. A usual way for a controlling shareholder to derive unfair benefits is to pay excessive compensation to himself and to executives and directors appointed by him. I do not think this is the case of Arhaus, but compensation is high anyway.

For example, according to the proxy statement, each director receives $75 thousand a year as an annual retainer, plus $110 thousand in restricted stock, also every year. Non-employee director compensation of $185 thousand per seat, for a board of 8 non-employee seats, is excessive. For 2021, the three top executives got $9 million cumulatively, $4.5 million of which were paid in cash.

Adjusting 2021 results

Because Arhaus went public in 2021, its financial statements include several one-time items that should be removed to find true operational profitability for the year.

For example, the term loan the company canceled in 2021 had cancellation fees equivalent to 4% of the company’s equity. Arhaus priced this liability at $64 million, $45 million of which were allocated to SG&A in 2021. Another $10 million in IPO related expenses were also allocated to SG&A. The after-tax effect of these costs is $41 million, considering an income tax rate of 25%.

Another adjustment needed is the removal of minority interest. Before the IPO, Arhaus had minority interests in some of its subsidiaries. After the IPO, these were consolidated, and therefore Arhaus does not have a significant minority interest anymore. However, on the 2021 statements, the minority interest was paid pro rata to November 2021, when the company did its IPO. The figure is about $16 million after taxes. Again we have to add them to net income.

Finally, by converting its structure to a corporation, Arhaus released tax assets that would not be usable otherwise. This allowed the company to write an income tax benefit provision of $10 million instead of an expense of $5 million. That means we need to adjust net income downwards by $15 million.

What we find then is that in an after IPO, recurring profit basis, Arhaus generated $63 million in after tax net income attributable to shareholders. This compared to the reported $21 million. To clarify, the company made no mistake reporting a lower figure, because minority interests had to be paid and because doing the IPO and canceling the debt meant additional expenses. However, in order to compare with 1H22 performance, it is better to adjust those figures.

1H22 performance

In the industry considerations section, I mentioned that Arhaus is exposed to cyclicality in the income of affluent households. In turn, according to Arhaus, high income customers’ demand is affected by declines in the stock market, rising interest rates and a decrease in the level of second and third home purchases.

All of the above stated conditions are in play during 1H22, therefore I would expect Arhaus to be affected by the new environment. Interestingly, the company’s revenues and profits continued growing during this period.

Before comparing the figures, a final accounting comment is needed. Arhaus recognizes revenue only when the products are delivered to the customer. Before that, orders build a liability called client deposits. This means that Arhaus builds a backlog. By reducing that backlog, Arhaus can increase revenue in periods where demand is falling. Therefore, in order to compare demand, one has to add the variation in client deposits to the variation in revenue.

In 1Q22 Arhaus reported $246 million in revenue against $238 million in 4Q21. However, client deposits grew by $42 million between 1Q22 and 4Q21, while they grew by $4 million between 4Q21 and 3Q21. This means 1Q22 demand was $294 million while 4Q21 demand was $242 million. This translates into 21% demand growth on a QoQ basis.

For 2Q22 Arhaus reported $306 million in revenue and a decrease of $38 million in client deposits. This adds to a total demand of $268 million, falling 9% on a QoQ basis, but still 11% above 4Q21 results. That is, in 2Q22 sold less than in 1Q21, showing signs of deterioration.

Arhaus reports a similar comparison but on a YoY basis. In its management commentary, the company reports both ‘comparable growth’, meaning revenue growth, and ‘demand comparable growth’, meaning variation in orders. On a YoY basis, 1H22 shows 15% demand growth.

From a demand perspective, the figures are still positive for the year, but a further reduction in 3Q22 compared to 2Q22 and 1Q21 would be a bad short-term sign.

This increase in demand, coupled operational leverage, generated a jump in profitability. The company posted $52 million in net income for 1H22, against adjusted $64 million for the whole FY21.

On a quarterly basis the situation is similar. 2Q22 revenue (not demand) was 24% higher than 1Q22 revenue. However, thanks to operational leverage, net income jumped 125%, from $16 million to $36 million.

Pricing and risks

On its 2Q22 earnings announcement, Arhaus management provided guidance for 2022. According to them the company will generate $92 million in net income this year. Compared to the adjusted figure of $63 million I calculated for 2021, that comes to 46% bottom line growth, in a not so good context.

The results have accompanied guidance up to 1H22. The question then is, why is a company growing its bottom line at 46% priced at an expected PE of 13 (market cap of $1.25 billion against expected net income of $92 million)?

As mentioned, my opinion is that the market fears two things.

First, that the founders will start slowly exiting the company, and therefore permanently depress the stock price. My take on this is that it is a real risk that is difficult to forecast, and the investor should ask for a higher rate of return.

Second, that the company’s revenue or demand will shrink, exposing the company to both downside operational leverage and restructuring expenses. This risk can be measured directly by comparing a variation in revenue with the resulting variation in net income.

For the assumptions, I calculated SG&A expenses of $175 million for 1H22, annualized to $350 million. Gross profit was adjusted to 45%. There are insignificant financial expenses and the income tax rate is 25%.

The company expects revenue of $1.2 billion for 2022, which translates to $92 million in net income. My model, with a higher gross margin but higher fixed SG&A costs, implies higher net income: $1.2 billion translates into $540 million gross profit, then $190 million operating profit and $143 million net income.

Here is the trick, if revenue ends up being 20% lower than expected for the year, closing at $950 million, still showing 18% YoY growth, my model estimates only $58 million in net income. That is a fall of 60% in net income compared to a fall of 20% in revenue. That is operating leverage at its finest. For the company to post that revenue for the year, 2H22 revenue should be 30% lower than 1H22 revenue. Remember that 2Q22 demand was already 10% lower than 1Q22 demand.

Operational leverage is real, and in my opinion that is the main reason the market is pricing ARHS so cheaply.

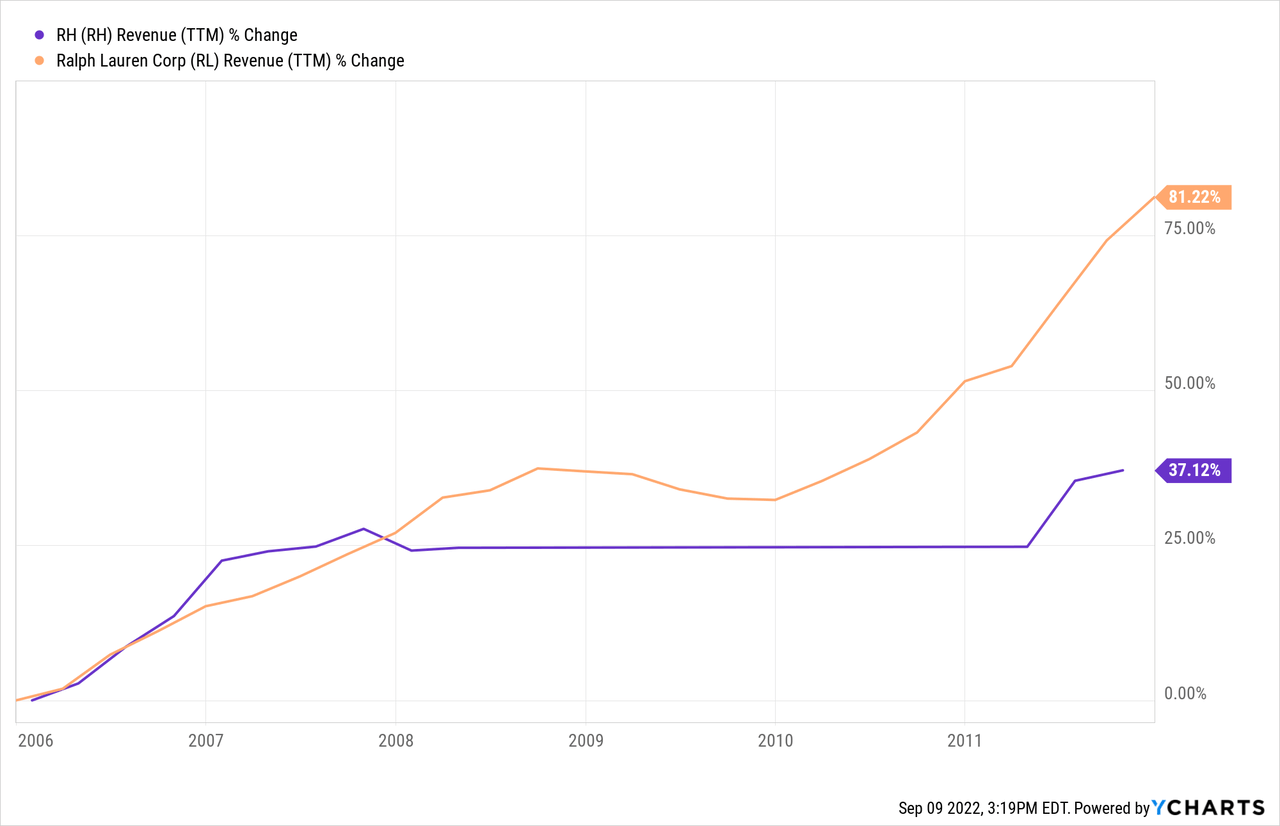

What is the chance of revenues stagnating? Unfortunately, there are not many public comparables to ARHS where we can watch what happened in the previous financial crisis.

The most direct comparison is Restoration Hardware (RH), which is directly related to luxury furniture. I also added Ralph Lauren (RL) which is not as comparable because it sells clothing and is not as luxurious. Other luxury retailers like Louis Vuitton (OTCPK:LVMHF) or Hermes (RMS) do not provide financial data for the Great Financial Crisis Period.

The chart below shows that if there is a crisis, luxury retailers do get hit. Maybe not with a reduction in revenue but with stagnation, which for us is just as terrible.

Finally, Arhaus cannot improve its profitability by reducing fixed expenses. If the company decided to close some locations and fire employees, then it would have to write millions in restructuring charges. These would be much higher than any savings for years to come.

It seems that, like Bill Gross used to say, Arhaus has to ‘grow or die’. Of course, Arhaus is probably not going to actually die, even in a recession. The company’s strength is its lack of debt. With $150 million in cash, the company could post losses for a few years without facing liquidity problems.

Conclusions

As I see it, the risk reward proposition here is a debt-free, growth story company selling at a value price, because its current earnings may shrink fast in a recessionary context.

It is very difficult to determine what will happen with the economy in general. I do not play that game. Therefore I consider ARHS to be fairly valued, which means I would not invest.

The long-term investor does not have a lot of margin of safety in this case. Some readers might want to play more speculatively, with smaller portions of their portfolio.

However, ARHS deserves close attention in the future. I believe the company has a lot of potential, it is just facing a complicated environment. Positive catalyst factors would be an increase in 3Q22 demand compared to both 2Q22 and 1Q22 demand, and a less volatile economic outlook for the US.

In order to improve the analysis, I hope Arhaus provides further detail on the variable or fixed nature of its expenses on its future reports with the SEC.

Also, if the stock falls to $7 again, like it did at the beginning of this year, then it may become a more reasonable investment. Of course, if that happens, new financial information will have to be included as well.

Be the first to comment