Pickett’s Charge Re-Enactment John Moore/Getty Images News

Introduction

On July 3, 1863, Confederate General Robert E. Lee was frustrated by the feeling that ultimate victory in the bloody Civil War was nearly in his grasp, yet somehow kept eluding him. After two days of nearly successful attacks on the massive Union army in Pennsylvania, he decided on the third day to gamble everything the South had on one throw of the dice. He ordered the massive frontal assault that became known as Pickett’s Charge (Wikipedia, 2022); this was to focus on the center of the Union lines arranged along the ridges south of Gettysburg. He chose his “old warhorse” Lt. General James Longstreet to plan and command the attack.

Longstreet famously objected that the Federals were too strong in the center of their line, that his old army colleague Maj. General Winfield S. Hancock led the Union center and was the best corps commander the North had, and that the Union army’s possession of the high ground guaranteed failure for this seemingly desperate Confederate frontal assault (Shelby Foote, 1958; The Civil War: A Narrative, Vol. 2; Random House, New York, 450pp.; William Garrett Piston, 1987; Lee’s Tarnished Lieutenant: James Longstreet and His Place in Southern History; The University of Georgia Press, Athens, Georgia; 252 pp.; Stephen W. Sears, 2003; Gettysburg; Houghton Mifflin Company, New York; 622 pp.).

Lee overruled Longstreet and told him to proceed with the planning. Longstreet was forced by his duty as a commander to order the attack, and off went thousands to their doom. As he had predicted, the assault was bloodily repulsed. The South never invaded the North again, and therefore the strategic initiative was forever lost as well. The Union went on to win the war (at great cost) in April, 1865. Lee’s mistakes at Gettysburg are taught in classes at military academies around the world, as an example of a great general making tragic mistakes in one pivotal battle that ultimately ruined his cause.

Why bring this Civil War story into a discussion of the actions of the Federal Reserve and Congress in trying to “manage” the economy right now? Because I think it serves as a kind of metaphor for where we are right now. Indeed, some observers are convinced that we are at a great turning point in the history of both monetary and fiscal policies, as the long period of fiscal profligacy enabled by the global fiat currency regime and de facto central bank debt monetization must soon reach its natural limits. This has recently been discussed at the annual Mauldin Economics investment conference by some pretty heavy hitters. These included former Fed regional bank president Thomas Hoenig, former Bank of International Settlements chief economist William White, and renowned private sector economist Lacy Hunt (John Mauldin, 2022a).

William White said that he fears the Fed is so far behind the curve and so incrementalistic under Chair Powell that they will be unable to stop inflation in time; such a failure (i.e., entrenched inflation) could lead eventually to a major currency crisis. White thinks the Fed is overconfident in their own ability and yet are using economic models that are grossly oversimplified and fundamentally wrong. Thomas Hoenig was a serial dissenter when he voted at FOMC meetings. Hoenig was against the perpetual “QE” policy of Fed Chair Bernanke, and he repeatedly voted against extensions of this foolish policy. Hoenig is concerned that the Fed will not see their inflation fight through to a successful finish – in other words he thinks they will blink when the going gets rough. As he points out, the Fed will be under tremendous pressure to reinstitute “QE” and “ZIRP” once we are perceived to be in a recession, and they will very likely cave in to that pressure. By trying to catch up (via combined rate increases and “QT”) after making a series of wrong calls on inflation, the risk of a recession has been increased, not ameliorated. And because they delayed in starting the fight until far too late, their actions will be widely seen as the primary cause of that new recession.

Lacy Hunt pointed out that inflation is hurting far more people than the strong job market is helping. Real wages have been falling (-3% “YOY”), a common indicator of an impending recession. Hunt also pointed out that the money multiplier has fallen very sharply since 2008, and since this is a measure of the fundamental demand for money, this downward trend under a simultaneous inflationary regime is extremely bad for the economy. This suggests that the inflationary pressure will be long-lasting. Furthermore, both the Fed and Congress, while sometimes speaking appropriately of the right things to do, are actually quite likely (based on their histories) to end up adopting catastrophically wrong policy solutions; this could ultimately be to our great cost for a short period of time. However, the silver lining would be that after the inevitable major crisis, the ever-expanding socialistic welfare state (both the concept and the reality) would at last be dead and buried. At issue then is the entire economic future of the country, with dire short-term consequences if we fail in our purpose at this great turning point, but possibly good long-term results once we have weathered the hurricane that would follow on the heels of our short-term failure.

So from a certain point of view, we face the economic equivalent of Pickett’s Charge; in other words an ill-advised and dangerously late attack on the problems we face that could potentially make everything worse for a while. Failure will mean not only that our problems multiply in the short run, but that they are simultaneously rendered almost completely intractable for quite some time. The good news hidden within this Civil War metaphor is that the USA recovered from that war as a re-united country, in spite of the South’s regionally devastating failure at Gettysburg. The economic sacrifices we fear are to be visited upon the American (and even global) population in the coming months and years will pave the way for an eventual change of direction that will be very positive in the long run. Investors will need some new strategies however, in order to survive until the good times return.

The Current Crisis and Its Causes

We came to this pass in part through a long cycle (from 1971 to the present) of an extremely expansive and wild government spending spree via the ever-expanding federal budget with its massive, embedded entitlement spending. We also arrived at this juncture through the serial passing of special fiscal packages put together to “help” with various economic crises, all legislated by Congress and signed by various presidents over the years. The entitlements and other mandatory spending are now at the estimated level for 2022 of $4.02 trillion, thus consuming over 80% of federal revenues, estimated for 2022 at $4.84 trillion based on “CBO” data (John Mauldin, 2022b). Included in the mandatory spending is interest on the cumulative debt, now estimated at $305 billion and growing rapidly (Kimberly Amadeo, 2022a).

The discretionary part of the budget (dominated by defense) comes to another $2.22 trillion, which leaves us with a federal deficit for the year of an estimated $1.40 trillion; note that the national debt is already at $30.427 trillion as of early June, 2022 (Peter G. Peterson Foundation, 2022). In 2007 before the almost endless “emergency” actions of the Fed and the repeated special fiscal packages of Congress (signed by three presidents), the national debt stood at a mere $9.01 trillion, or 62% of “GDP.” The 2021 level of the national debt, some $29.67 trillion, had soared in the intervening 14 years to more than triple the 2007 level, or about 124% of “GDP” (Kimberly Amadeo, 2022b).

Special fiscal packages were passed by Congress to “help” with the Great Financial Crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic, along with an urgent need to “invest” in improved infrastructure; these all added massive amounts to the national debt, and these were all done on a bipartisan basis. Incredibly, $5.74 trillion was spent on “helicopter money” and other forms of stimulus for the (self-induced) pandemic crisis alone (Nicholas Wu & Javier Zarracina, 2021). Thus in total some $8.3 trillion was added to the debt via bloated budgets, huge new entitlements, and massive special fiscal “stimulus” packages under President Obama’s administration; another $7.8 trillion was added under President Trump’s administration, in half the time, due to the Covid-19 pandemic, big boosts to defense spending, and the delayed impacts of the Obama spending decisions; so far, in just 18 months, another $2.26 trillion has been added to the debt under President Biden’s administration, and he wanted much, much more than that (Kimberly Amadeo, 2022c).

Lest we think taxes weren’t quite high enough during those last 14-plus years (and objectively they did not come close to covering the spending), it is important to note that individual federal income tax revenues soared to $1.93 trillion in 2021, and are estimated to come in at an all-time high of $2.60 trillion for 2022 (Richard Rubin & Amara Omeokwe, 2022; Individual Income Tax Payments on Pace to Reach Record Level). In 2021 another $1.37 trillion of federal revenues came from regressive payroll taxes, but only a paltry $284 billion from corporate income taxes; all other taxes plus the Federal Reserve’s earnings on their balance sheet holdings came to $274 billion in 2021 (Kimberly Amadeo, 2021). That totals around $3.86 trillion for 2021; the current estimate for 2022 is that revenues have soared to $4.84 trillion, as mentioned above. Yet the deficit will still add some $1.40 trillion to the national debt, also as noted above.

As I have stated elsewhere (Kevin Wilson, 2019a; The Yellow Submarine Fantasy (Part I): What If We Actually Tried To Solve Our Economic Problems?), we give far more “corporate welfare” in the form of tax preference items than we take in as revenue from corporations. Indeed, way back in 2016 corporate tax preference items already amounted to $1.40 trillion per year in lower taxes for corporations, a sum that is equal to this year’s entire deficit (Annette Nellen, 2016; House Republicans Offer ‘A Better Way’ for Taxes). This has risen since 2016, although the mix of companies benefiting is constantly changing. This can’t all be good for the country; in fact significant amounts of it could be characterized as corporate welfare or even crony capitalism (Kevin Wilson, 2019b; Pie Plate Economics And The Campaign For A More Intrusive Administrative State). Indeed, we’ve observed a steadily falling share of the federal tax burden carried by corporations for decades.

But in spite of that trend, federal corporate tax revenues could reach a record $454 billion this year in nominal terms, or about 1.9% of “GDP” (William McBride, 2022). This is a recent high, but does not compare well with the 2.7% of “GDP” corporate contribution to federal revenues that occurred as recently as 2007. During the 14 years since 2007, corporate earnings have soared to the highest levels ever, and profit margins have also soared to unheard-of levels. So some significant part of corporate tax preference items should probably be eliminated to improve the fairness of the tax code and provide more revenue. However, since nearly the entire elected federal government (both parties) is gleefully corrupt and has been profoundly co-opted by corporate interests, major change is unlikely in the near future.

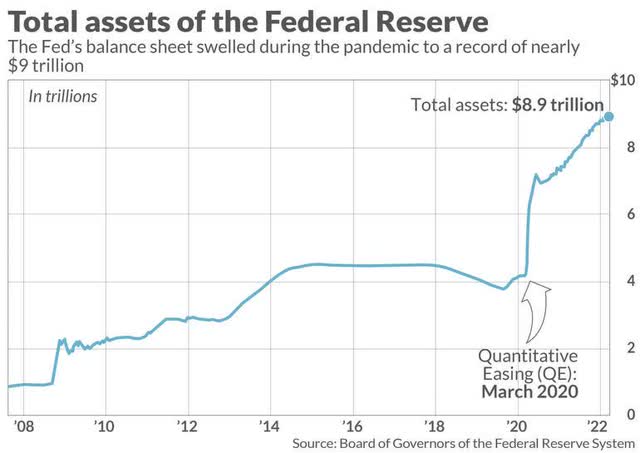

About half of the above-mentioned, massive deficit spending could never have happened over the last 14 years without the enabling actions of an irresponsible and politically-motivated Federal Reserve (Kevin Wilson, 2019c; ‘Yes, We Have No Bananas’: The Fed Can’t Give Us What We Need). This remains true even if we subtract the savings produced by Fed-induced artificially low rates of interest on the debt. The Fed’s members have been enablers because they have directly “monetized” (in a way) portions of the debt through Quantitative Easing (“QE”), and they have kept policies like “ZIRP” in place for huge stretches of time, reducing the cost of interest on government debt, which I believe is one of their primary goals, whether they admit it or not. As a result of all the Fed largesse since 2007, the Fed’s balance sheet has soared to almost $9 trillion due to the purchase of Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities (“MBS”), as shown in Chart 1 below. So a “temporary, emergency measure” has seemingly become a permanent mainstay of Fed policy, distorting the markets and the economy in ways never seen before.

Chart 1: The Fed’s QE Programs Have Blown Up Its Balance Sheet

Total US public debt increased by $19.42 trillion between 2008 and 2021, but the Fed covered $7.99 trillion (41%) of that new debt issuance with “temporary QE” purchases. This is not strictly debt monetization (cf. Yale School of Management, 2020), but it has essentially the same effect, in that government bond markets were not destroyed (as they should have been) by the massive over-issuance of government debt. This is primarily because the Fed bought so much of it. Thus, normal market limitations (i.e., the impact of higher yields) did not occur, removing any natural constraints on government spending. Indeed, “QE” is the Fed’s nearly perpetual gift to the welfare state, and maybe to American socialism as well. In any case, the Fed’s balance sheet will still technically qualify as real debt financing or monetization unless it is actually quantitatively sold back to the private sector; this is an event that is highly improbable (Adair Turner, 2020).

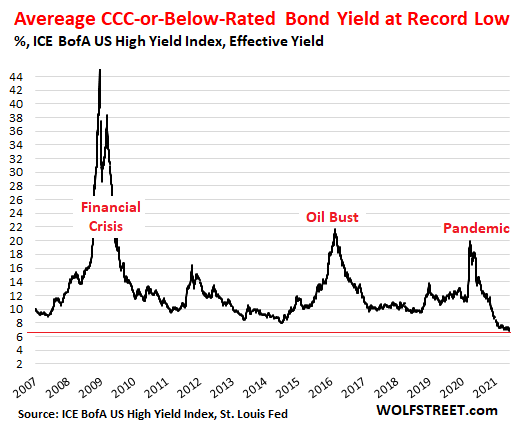

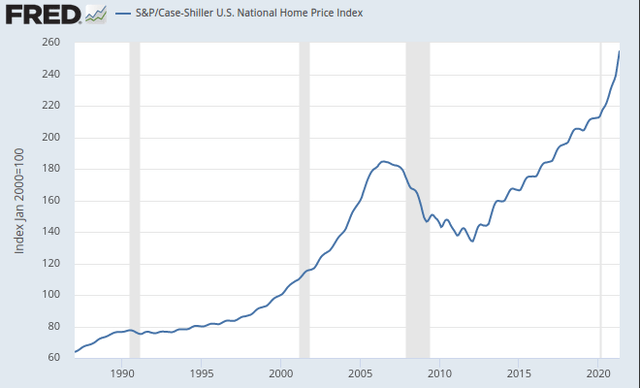

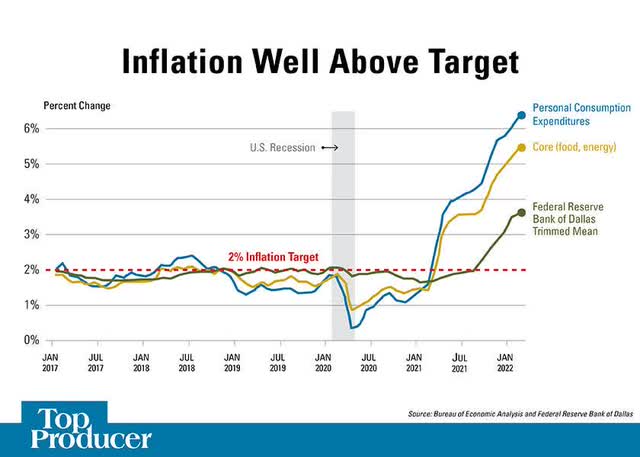

Now we appear to have the inflation that commonly accompanies debt monetization (Yale School of Management, 2020; Op. cit.), especially when “helicopter money” is involved (as it was during the pandemic), although it can still be argued that a major part of the current inflation is just a supply driven issue soon to be resolved by decreased demand, especially as we now appear to be on our way to a Fed-induced recession (Wendy Edelberg, 2021; What does current inflation tell us about the future?). Initially this inflation was restricted to risk assets, but now the disease has spread to the real economy. Thus, because of the combination of profligate federal fiscal policies, mindless pandemic policies, and irresponsible Fed monetary policies we now have the most inflated asset prices, by some measures, that the markets (e.g., stock, junk bond, commodities, and housing) have ever seen, as shown in Charts 2, 3, and 4. These are a reflection of the “everything bubble” produced by almost 14 years of exceedingly low rates and over $8 trillion of “QE,” along with massive distributions of federal “helicopter money.”

Chart 2: Soaring Market Price/Sales Ratio Now the Highest Ever

Chart 3: Highest Ever CCC-Rated Bond Prices (Lowest Yields)

Wolfstreet.com

Chart 4: A New Housing Bubble That Easily Rivals the One That

Peaked in 2007

News.bitcoin.com, Federal Reserve

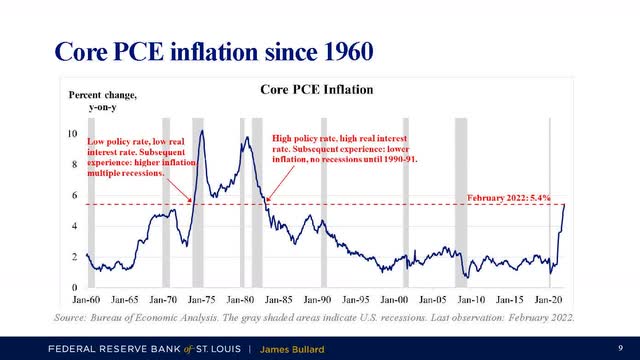

Inflation of essentially everything is now the great problem being wrestled with by the fiscal and monetary authorities, and so far they are losing hands down (Chart 5). Gasoline topped $5/gallon nationally in mid-June, natural gas prices are now the highest since the huge price spikes of 2005-2008, and food costs have soared (Jaewon Kang & Annie Gasparro, 2022). One common question is whether the inflation spike we’re seeing is temporary or permanent; reasonable arguments support either answer, but I would submit that once certain supply bottlenecks are cleared, the ultimate answer will depend on what the Fed and Congress do going forward. Both entities have an almost insane need to meddle with things, and are absolutely fearless in doing so. This lack of concern or caution is partly a result of ignorance about how things actually work, partly due to the arrogance that comes with having no skin in the game, and partly due to the perceived political necessity of supporting the welfare state no matter what the cost may be. Just out of a sort of academic interest then, how is it that both the fiscal and monetary authorities managed to become simultaneously trapped in their currently shared dilemma?

Chart 5: The Fed Overshot Its Target Just A Wee Bit

Agweb.com, BEA, Federal Reserve

First, congressional and administration budget proposals that are actually approved legislatively are reliably biased towards ever more spending regardless of the lack of revenues to support the increases. Childish games are played, like recording hundreds of billions of dollars per year as “off-balance sheet” so they can be excluded from the deficit (but not the additions to debt, which are not as well-covered by the media). Second, the massive special spending packages mentioned above were pushed by successive administrations regardless of any actual (lasting) economic benefit or any potential boost to inflation rates, which for political reasons was generally termed a “highly unlikely” event. Third, the pandemic lockdown rules enhanced the chances that supply and demand would be knocked out of kilter, and the “helicopter money” spewed out by the special spending packages jacked up demand in the middle of a massive supply shortage (i.e., “too much money chasing too few goods”). Fourth, “QE” was continued long after the case for it could be justified, as is typical of the irresponsible Federal Reserve (cf. Kevin Wilson, 2020; Monetary Policy Is Very Exciting — As A Luggage Problem). And fifth, low interest rates (“ZIRP”) were also continued far longer than necessary, again as is typical of the Fed.

The Economic Equivalent of Pickett’s Charge?

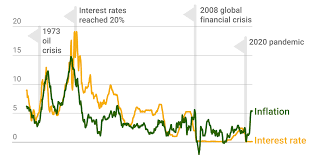

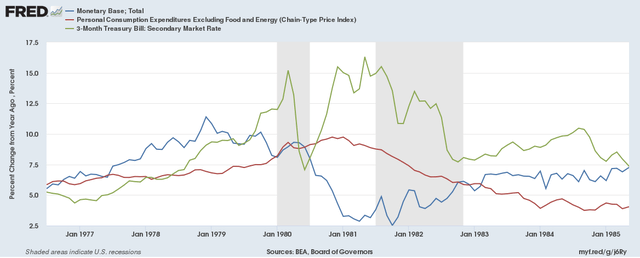

So now we have the Fed lagging far, far behind the curve with ridiculously low rates and “QE” in place until just a few weeks ago (Charts 6 and 7). They’re now being forced for political and other practical reasons to pivot to a supposedly “Paul Volcker” style in order to catch up and eventually crush inflation. However, when Fed Chair Paul Volcker crushed inflation in 1979-1983, there were two back-to-back recessions, and one of them was quite severe (Kevin Wilson, 2018; Money For Nothing: When Fiscal And Monetary Policy Fail Simultaneously (Part II)). The same thing, i.e., at least one severe recession, is likely to happen now, because inflation won’t be crushed unless the demand helping to drive it is crushed, and that is what the Fed has finally set out (belatedly) to do (Mark Zandi, quoted by Matt Egan, 2022; Recession risks are ‘uncomfortably high and moving higher,’ Mark Zandi says; Liz Ann Sonders & Kevin Gordon, 2022; Signs Point to Rising Recession Risk).

Chart 6: Fed Funds Rates vs. Inflation Through October, 2021

Gzeromedia.com

Chart 7: The Fed’s Low Policy Rates and Low Real Interest Rates

Have Again Helped Trigger High Inflation

The difficulties that the Fed will face in taming the inflation beast have recently been pointed out by former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers and colleagues, who have written a new paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research. In this work (M. A. Bolhuis, J. N. L. Cramer & L. H. Summers, 2022); these economists refigured long term inflation data so that the present dilemma can be compared to the data from the Great Inflation (1973-1983). The adjustments they came up with have the effect of reducing the maximum core inflation rate from 13.6% in June 1980, to a refigured 9.1%; the trough rate of 2.5% for core inflation under the Volcker Fed (in 1983) is raised under this system to about 4.1%. They conclude that the effectiveness of Fed Policy under Chair Volcker has been exaggerated by inflation methodologies that were somewhat inaccurate, and that the actual decline in rates he produced with his then-new policies was only around 5%, rather than the 11% generally attributed to the disinflation he initiated.

Of course, we all know that the Volcker Fed’s actions still worked, so that’s fine as far as it goes. Note however, that Volcker’s Fed raised rates a total of around 10% in order to drop inflation by an adjusted 5% (Patti Domm, 2019; When Volcker ruled the Fed, ‘people thought they’d never buy a home again’). Bolhuis, Cramer and Summers (2022) also point out that these smaller numbers for Great Inflation rate reductions mean that when today’s inflation problem is compared to that time (1979-1983) under Chair Volcker on an apples-to-apples basis, the Powell Fed actually faces much the same level of problem that the Volcker Fed did. It will again need to drop rates by around 5%, a much taller order than has generally been perceived by Wall Street and the investment media. Only about half that much has been mentioned in most media or Wall Street analyses. Can Chair Powell really raise rates 5-10% to achieve the same kind of deflationary trend that Volcker’s Fed pulled off? In order to drop inflation rates that far, the Powell Fed must also generate truly massive demand destruction, just as the Volcker Fed did. The questions that arise in light of these data include: 1) does the current Fed have the tools to do the job?; 2) does the current Fed have the will power to see this through?; and 3) will the generally clueless Congress and the monumentally clueless Biden Administration sit still for this? We can’t know these answers for sure, but we can make some educated guesses.

For one thing, high inflation itself, along with the initial tightening actions of the Fed, have in combination already triggered significant demand destruction, as evidenced by new single-family home sales coming down 27% “YOY,” and light vehicle sales coming down 25% “YOY” in the latest reports (David Rosenberg, “Early Morning With Dave Report for June 7, 2022;” Publications – Rosenberg Research [behind paywall]). There’s also the fact that real GDP growth was negative (-1.5%) for the First Quarter, and it’s already tracking as low as 0.9% for the Second Quarter according to the Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow forecast, with a few weeks of declining activity left to go, so a second negative print is possible (Lance Roberts, 2022). Consumer credit growth has also spiked in recent months, and this is often a harbinger of recessions. Even the normally optimistic Bank of America (BAC) has issued a recession warning recently via their chief investment strategist, Michael Hartnett (Emel Akan, 2022; Bank of America Warns of Future Inflation Shocks, Declares ‘Technical Recession’). So to some extent we can already see evidence of significant, but not yet sufficient, demand destruction.

It is also important to note that the reversing of “QE” via Quantitative Tightening (“QT”) is a powerful additional means of raising effective rates because the liquidity that blew up the “everything bubble” is now being actively reduced, and at a pretty ferocious clip. The current Federal Reserve plan is to roll off about $530 billion of assets from their balance sheet by year-end 2022, with another $1.14 trillion coming off in 2023. This is tantamount to significant additional “effective” rate increases equivalent to 25 bp this year and a bit more than 50 bp for next year, according to the Fed itself (Bryan Rich, 2022; Pro Perspectives 6/1/22). This would mean a total “effective” planned (or projected) rate increase of around 2.75% this year and perhaps another 2.50% next year. Cumulatively, this would reach 5.25% on the rate increase side of the ledger, but would that be enough? Volcker had to raise rates by almost double that amount.

This could quite possibly be a problem, although in all fairness, the collapse of the “everything bubble” could cause so much hardship in what will undoubtedly be a global recession starting later this year, that perhaps the goal could come pretty close to being met (in the short run) by the currently planned program. But that assumes that: 1) the incrementalism of the Powell Fed will work in the same way, only slower, as the “shock and awe” program used by the Volcker Fed; 2) Congress and the Fed will not react to the coming recession by respectively legislating huge stimulus spending packages and returning to “ZIRP” and “QE;” and 3) inflation will not return after the recession is over. The latter two assumptions seem highly unlikely to me, because the long-term structural problem created by Congressional spending and Fed economic engineering is not very likely to be permanently resolved with just one recession, even if it is fairly serious.

A fundamental change in the trend of federal spending patterns and Federal Reserve monetary policies would help avoid this, but neither seems likely to happen, short of a total catastrophe like a currency devaluation. Indeed, the Great Inflation was ended only after the second, very severe recession of the early 1980s smashed rates just 18 months or so after the first recession had already taken rates down quite a bit (Chart 8). So, unless both Congress and the Fed wake up and smell the coffee, we are in for a very long and uncomfortable ride. Neither has shown the slightest interest in actually solving the long-term problem, and unless there’s a global currency crisis and devaluation similar to that in the Great Depression, I fear they never will.

Chart 8: The Volcker Fed’s Efforts Had to be Redoubled After the First Recession in 1980

Fisher Investments, Federal Reserve

Conclusion

The Federal Reserve faces quite a dilemma in how to execute their war on inflation. Congress faces an election year in the midst of high inflation and an impending recession. The metaphor of Pickett’s Charge at Gettysburg comes to my mind in this situation, because the Confederacy’s General Robert E. Lee also faced a huge dilemma. Lee understood that there were great risks in a frontal attack on the entrenched Northern positions on the hills south of the town. But Lee also wanted to bring the bloody and terrible war to a rapid conclusion. He knew that the cost to his army would be high, but he believed it was worth it. So in spite of all the obstacles, Lee ordered the ultimately disastrous attack. In fact as General Longstreet had feared, the South never recovered from their defeat at Gettysburg. Ultimately however, the Union was saved, and the great injury to the Republic caused by the Civil War and by slavery began to be healed.

Congress and the Federal Reserve face far less dangerous choices than General Lee faced, but they nevertheless find the national economy at a turning point, and the consequences of a major mistake now would be dire for many millions of people. The Fed looks at core inflation as their key for decision making; it was recently at 6.00%. Consumers and Wall Street, however, look at headline inflation, which just hit a 40-year high of 8.6%. A decent proxy for core inflation is lumber prices, according to Tan Kai Xian of GaveKal Research (Mauldin Economics, 2022b). Lumber prices have already fallen -60% in the last 90 days as Fed-induced rising rates caused the housing market to collapse, and this trend is expected to continue. So core “CPI” should fall. However, if we look at a proxy for headline “CPI,” e.g., oil prices, the situation is far more intractable, according to Tan Kai Xian. There are structural factors limiting new energy production that will continue to drive oil prices higher until consumer demand is substantially crushed (as it usually is by a recession at some point). But this time around the structural problems will persist because companies have not spent enough on the exploration for, or the exploitation of new energy resources for some time now. Since lead times are long in the energy business, it will be a long time (5-7 years) before supply can catch up to demand, unless a recession crushes that demand for a while.

If the Fed wavers under pressure from Congress and/or the Administration, putting “QE” and “ZIRP” back in place, then demand will bounce back and headline “CPI” will bounce back sharply, proving to be quite sticky. So to actually succeed in their war on inflation, the Federal Reserve must destroy demand, trigger an election year recession, and then refuse to return to the easy money policies of the last 14 years. This seems like a tall order, firstly because it’s obvious that the Fed has no actual plan driving their decisions, and secondly because Chair Powell is notorious for his sudden pivots in policy direction when the pressure is high. The “FOMC” appears to be made up mostly of “nodders” (seat-warmers who always vote in favor of whatever the Chair proposes), so good luck getting any dissent from them if Powell goes the wrong way (which he has already done for years). It is far more likely that the Fed fails than that they succeed, in my opinion.

Congress faces an unusually divisive election year and in general doesn’t have a clue about economics anyway. Is it possible that they will ignore the effects of a deep recession and refuse to pass a big “emergency” spending bill once that recession is confirmed? Sure it’s possible, just like it’s also theoretically possible for Elon Musk to live on Mars; but it is highly unlikely in the short run. Another “helicopter money” drop is even possible if the recession is bad enough, even though the money drops already done during the Covid-19 pandemic were demonstrably major contributors to our current dilemma. So the odds are that both the Fed and Congress will fail in their war against inflation.

Assuming a comprehensive failure to bring headline inflation under control, what seems likely to happen? It’s of course unknowable, but one possibility in this scenario is that inflation becomes deeply entrenched and is eventually deemed to be permanent in the public (and investor) mind. If that happens, presumably after the now-impending recession has ended, the recovery would be very slow, like it was after the Great Financial Crisis. High inflation would return, and stagflation might become the catchword of the times. But far, far worse would be the global market reaction to a USA that is growing its debt parabolically and de facto monetizing it as it goes. Witness the dangerous decline of the Japanese yen as the Bank of Japan persists in its infinite “QE” and equally infinite government debt monetization. A currency crisis in Asia could soon result if that trend continues.

So the dollar would at some point plummet to unheard-of lows, and the USA could eventually be forced into the first currency devaluation in almost a century, with catastrophic results for the middle class and the poor. The trouble could spread globally (Kevin Wilson, 2018; Ignorance, Denial And Global Default). The American Dream might be dead for yet another generation. The suffering that could result from this scenario might at some point compare with that of the Great Depression. Sound crazy? Maybe, but we are just as accidental and haphazard in choosing our economic pathway as the generation of the Roaring Twenties. Who amongst that generation predicted the Great Depression while there was still time to act? Almost no one could even imagine such a thing after so many years in the sun. Many famous people (e.g., Groucho Marx) lost everything and even the great economist Irving Fisher was caught unawares, to his great reputational and financial cost.

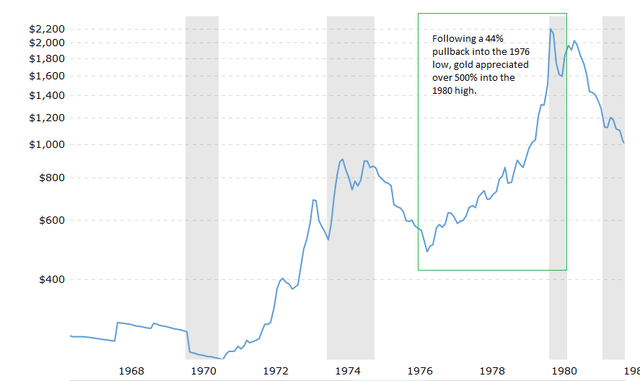

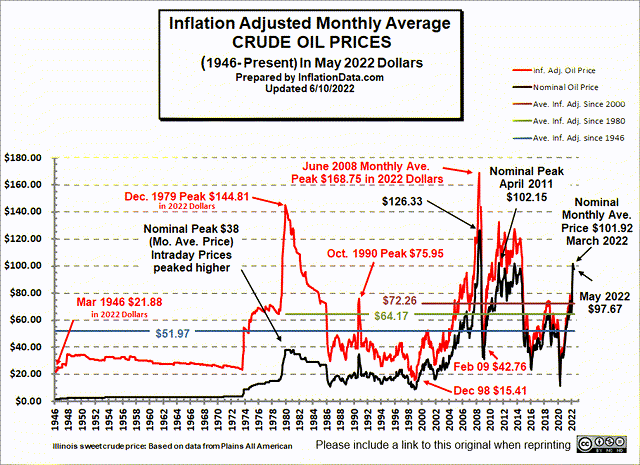

What should investors do? This is a very tough question, because it hinges on what various economic actors may or may not do, and uncertainty is necessarily very high here. Two things are clear however: 1) gold would do very well in the event the worst happens with regard to inflation and/or currency devaluation; and 2) real asset-based stocks (e.g., energy, mining, real estate) would outperform everything else except perhaps gold in a stagflation scenario. High inflation or stagflation could easily happen in the wake of the impending recession, especially if both the fed and Congress fail in their anti-inflation missions. Look at what happened to gold prices in the Great Inflation: they absolutely soared (Chart 9). Not just physical gold, but also gold mining stocks did very well during the Great Inflation. Energy (crude oil) prices also soared (Chart 10) due to a global supply shock lasting from 1973-1983; energy-related stocks also did very well during that period. Today one could make money on the long term inflation threat by investing in the physical gold exchange traded funds, such as the Sprott Physical Gold Trust (PHYS), and the gold mining stock funds, such as VanEck Gold Miners (GDX) and VanEck Junior Gold Miners (GDXJ). Energy “ETFs” like Energy Select Sector SPDR Fund (XLE) might do well also in the presumed inflationary period after the recession, as would some high dividend-paying individual stocks, such as the giants Exxon Mobil Corp. (XOM), Chevron Corporation (CVX), ConocoPhillips (COP), Shell plc (SHEL), and TotalEnergies SE (TTE). Real estate “ETFs” such as Real Estate Select Sector SPDR Fund (XLRE) might also be a good bet after the recession.

Chart 9: The Great Gold Rally of 1976-1980

Chart 10: The Huge Oil Rally of 1973-1985

Be the first to comment