Onfokus/E+ via Getty Images

Sri Lanka in turmoil. The South Asian island off the southern coast of India has descended into political and economic crisis. The consequences from years of misguided economic policies and massive indebtedness have finally come due amid soaring inflation and rising interest rates. The country has already defaulted on its debt, and mounting food and energy shortages have boiled over into social unrest, which is forcing a leadership upheaval. A tragic story to be certain. But given that the Sri Lankan economy is smaller than the state of West Virginia’s on a nominal GDP basis, why does it matter from a global financial market perspective? Because what is taking place in Sri Lanka today is only the tip of the iceberg of what is likely to come in the months ahead.

Minimal direct exposure. It is extremely likely that most investors have had little to no direct exposure to Sri Lanka in their investment portfolios. From a stock perspective, about the only way most investors would have any allocation to Sri Lanka is through holding the iShares MSCI Frontier and Select EM ETF (FM), which has a less than 1% weighting to a small handful of names from the country’s stock market. And given that frontier markets are a step beyond emerging markets from a risk perspective, such an allocation to FM is likely for the more intrepid investors anyway.

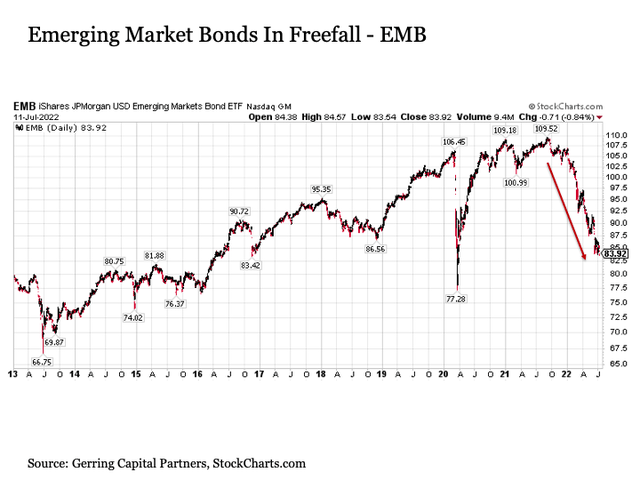

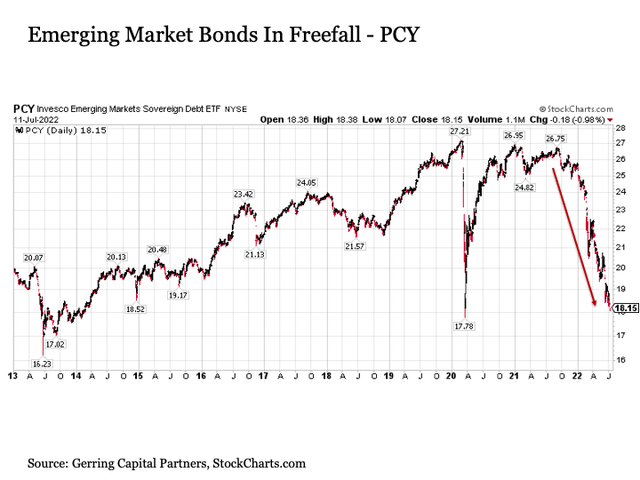

Where some investors may unwittingly have had a more nominal direct exposure to Sri Lanka is through their bond allocations. Most notably, two of the oldest and largest emerging market debt ETFs – the iShares J.P. Morgan USD Emerging Markets Bond ETF (EMB) and the Invesco Emerging Markets Sovereign Debt Portfolio ETF (PCY) – both have had allocations to Sri Lanka ranging from roughly 0.5% to more than 2.5%. And given the tireless chase for yield that so many investors have engaged since the Great Financial Crisis, it is not uncommon for investors to find a decent sized slug of either of these ETFs or other emerging market debt ETFs like them in their portfolio.

Nonetheless, the direct portfolio impact associated with the economic turmoil in Sri Lanka is still likely very minimal.

But here is the problem. What’s taking place right now is not just about Sri Lanka. It’s about a burgeoning crisis that is unfolding across the developing world. And the more the problem spreads, the more likely its negative effects will spill over into the developed world. This is what we used to call financial contagion.

A butterfly once flapped its wings in Thailand back in the summer of 1997. A year later, much of Asia including Russia was embroiled in a financial crisis, and the global financial system was driven to the brink by the collapse of all-star hedge fund Long-Term Capital Management.

Of course, the global economy and its financial system is different a quarter of a century later. But the similarity remains that we have a number of emerging economies across the global that are loaded up beyond their eyeballs in debt thanks to more than a decade of ultra-easy money from global central banks that they are now finding a hard time to roll over or pay back now that interest rates are spiking higher, the U.S. dollar is strengthening (many countries have borrowed in U.S. dollar denominated debt and need to exchange their rapidly weakening local currencies into U.S. dollars to pay off this debt, which effectively means their debt bills are now increasingly exploding), and liquidity is quickly draining from the global financial system (in other words, fewer remaining investors have the money or are willing to take the risk to step in and buy the debt that is becoming increasingly unlikely to be repaid anyway).

Unfortunately, the key difference today versus the late 1990s is that while we were basking in a global disinflationary environment that afforded global central banks the flexibility to provide what we now know as “whatever it takes” style policy support to ease the pain on these ailing emerging economies, today central banks are fully engaged in a raging inflation fight that is as bad as we have seen in nearly a half century. In short, while the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or friendly countries might pitch in to lend a strings-attached hand if they can, the easy money can-kicking days where global central banks could print away our financial troubles for another day are over. The time to pay the piper has come.

Who’s next? Sri Lanka is certainly not alone in standing on the economic and financial brink. The island nation defaulted on its debt in May, and it was quickly joined by Russia in June. Of course, Russia is a special case given its unprovoked invasion of another country in Ukraine and its subsequently imposed economic isolation from much of the rest of the world. What other countries might be next?

Consider the following list of countries from a purely quantitative perspective whose sovereign debt according to the JP Morgan Emerging Market Debt Index is currently trading with a yield to maturity above 10%, which implies varying magnitudes of economic and financial stress depending on how far above 10% their government bonds are yielding. This is list of countries that will be worth monitoring, among others, as potential sources of stress in the months ahead. The following list excludes Ethiopia, Lebanon, Venezuela, Zambia, Sri Lanka, and Russia, all of which are already in default and are now in varying stages of restructuring if applicable.

Country – YTM (%)

Ukraine – 50%

Argentina – 43%

Tunisia – 33%

El Salvador – 30%

Pakistan – 28%

Ghana – 22%

Kenya – 18%

Ecuador – 18%

Egypt – 15%

Nigeria – 14%

South Africa – 14%

Angola – 13%

Gabon – 13%

Senegal – 11%

Turkey – 11%

Mexico – 11%

Bolivia – 11%

Iraq – 11%

Senegal – 10%

Jordan – 10%

It is important to note from the outset that the twenty countries listed above are not necessarily going to default on their debt in the coming months. In fact, none of the above may default at the end of the day. It is still worth noting that the sovereign bonds from the countries listed above are trading at discounts to par anywhere between 25% and 80% in many cases.

Needless to say, many of countries are what would be described as distressed debt situations. And unlike Sri Lanka in isolation, this is a sizeable list whose combined weight makes up as much as 20% to 25% of the major emerging market debt products like EMB and PCY introduced above. This is how we end up with cascading price charts for these products as shown below.

StockCharts

In the case of EMB, it is already down by -25% from its highs from late last year and is quickly closing in on its COVID crisis lows and levels last seen seven years ago in 2015.

StockCharts

As for the more equally weighted PCY, the damage so far is even more profound. It is already lower by more than 33% from last year’s highs, and it is fast tracking its way past COVID lows and levels last seen a decade ago in 2013.

The losses in the emerging market debt space have already been staggering, and we may very well only be at the beginning of the considerable further downside that appears to lie ahead for this troubled asset class category.

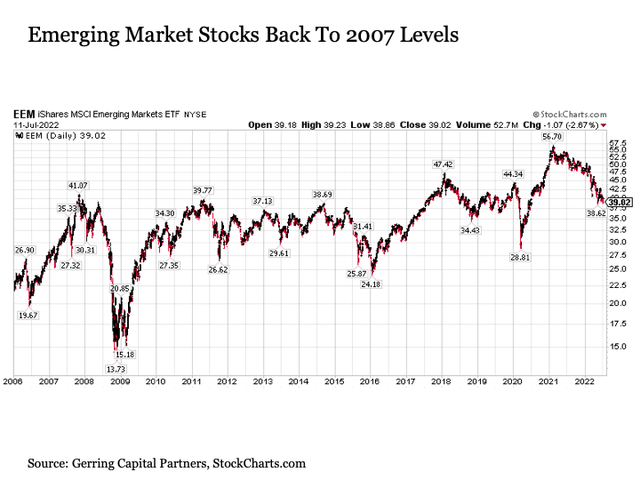

Bond problems are stock problems. Many stock investors may think they are immune to this issue. Some might say “this is a bond problem, but who cares since I own stocks?”. Here’s the thing. As the events of the Great Financial Crisis showed us, if the bond market isn’t happy, the stock market isn’t going to be happy either. Yes, the emerging market debt marketplace is a more specialized category with only $24 billion on an ETF asset basis according to VettaFi. But the emerging market stock category at $207 billion in ETF assets is a much more widely held asset class.

Why would a government bond problem in emerging markets weigh on the stocks of companies in these same markets? Here’s one of many reasons – the major banks in most of these markets are major holders of their country’s sovereign debt. So if the price of this debt is plunging by as much as 25% to 80%, this represents a significant balance sheet impairment for these major banks. And if the banking system becomes not well capitalized, they are likely to significantly curtail lending activity to the local companies in these markets. This not only hurts economic growth but corporate profitability, valuations, and the stock price.

Needless to say, emerging market stocks have also been getting savaged to the downside for nearly 18 months now.

StockCharts

Not only are emerging market stocks down -31% from their early 2021 highs that foreshadowed what was eventually to come for so many other risk assets across capital markets, they have returned to levels first reached 15 years ago back in 2007. And if the debt issue in emerging markets is likely to deteriorate further, it is also likely that we are far from a bottom in emerging market stocks as well.

No escape. Many investors may still conclude they are immune from these risks. Some might say “emerging markets are risky, and the prospects appear lousy, so I’ll just stay away and focus on investing in the U.S.” If only it were this simple.

While we are transitioning away somewhat in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and some of the political upheaval that continues to unfold worldwide, the reality remains that we continue to operate in a globalized, interconnected world. This is particularly true of the global financial system. So if a butterfly flaps its wings in Sri Lanka in an environment of deteriorating global economic growth, stubbornly high global inflation, and waning global liquidity, the threat of a hurricane eventually arriving on U.S. financial shores is real.

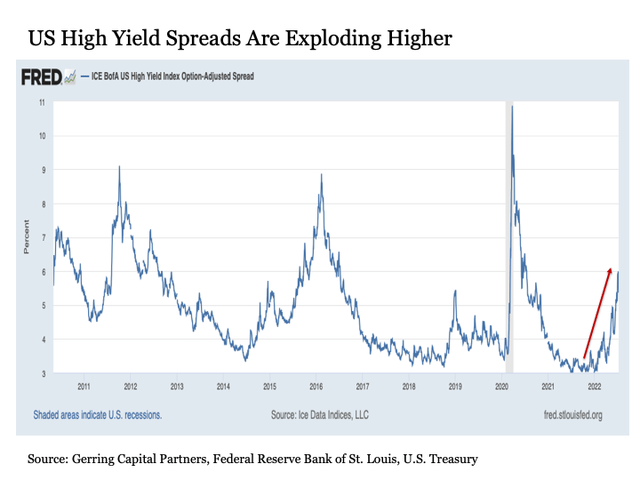

How would this happen? Consider one sign of financial stress already on the rise in the U.S. The following is a chart of high yield spreads relative to comparably dated U.S. Treasuries. After reaching post GFC lows of 3% at the very end of 2021, high yield spreads have since exploded higher to north of 6%, which is already the highest level in more than five years save the COVID blip in early 2020. And these spreads appear poised to continue higher in the months ahead given the economic outlook and the persistent direction of interest rates.

StockCharts

In short, we are also seeing signs of stress building under the surface in the United States. As a result, we are not operating from a position of core strength once the spillover effects from emerging markets start reaching the U.S.

Taking this one step further, U.S. markets are also at risk given the extreme amount of leverage that remains in the system despite what has already been considerable losses so far this year.

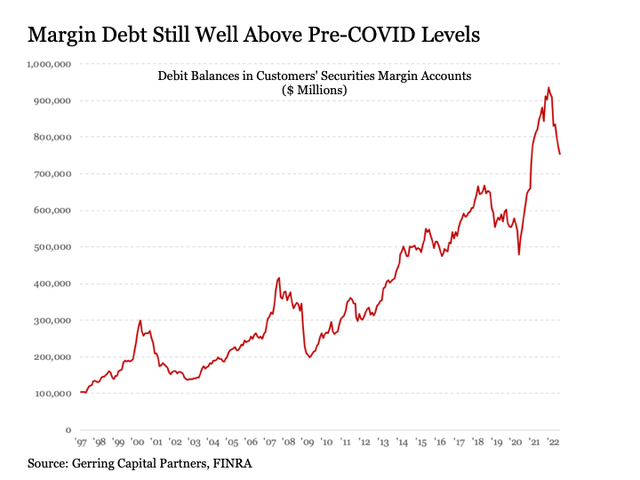

Consider the following chart of margin debt as just one example.

StockCharts

While margin debt is nearly -20% lower from its October 2021 highs, it is still +38% above pre-COVID levels. Given that margin debt previously returned to pre-market cycle levels before the market finally bottomed in the three past episodes from 2000, 2007, and 2018, it is reasonable to expect that margin levels have considerably further to go to the downside to fully “come down the other side of the mountain” from a speculative standpoint.

How does signs of still high leverage in the U.S. connect with the problems that are increasingly unfolding across emerging markets?

Because how many institutional investors and hedge funds got all levered up on easy money over the last many years and thought they were too smart for their own good by putting on some complex trade on in emerging markets and are now starting to squirm. Or maybe they have no idea yet how far over their skis they are with a certain trade set up across these developing regions, but may eventually find out.

How many new Long-Term Capital Management equivalents are lurking in the investment market shadows? I suspect at least a few. And how the Fed handles this challenge in a lingeringly high inflation environment will be interesting to see if it comes to pass. But it is hardly the stuff of rising stock prices and higher valuation multiples. To the contrary, it is the exact opposite.

And in the better case scenario, as global market including both emerging markets and the U.S. continue to fall and the margin clerks increasingly make the rounds with the proverbial taps on the shoulder, what will these institutions and hedge funds sell in order to raise cash to settle their margin accounts? Typically, it’s the most liquid names like U.S. exchange traded stocks that get thrown overboard first.

The bottom line. At first glance, the situation currently unfolding today in Sri Lanka may not seem like an important issue for investors. But the problem plaguing Sri Lanka today threatens to spread across a number of developing world locations in the coming months. If a contagion event starts to unfold, it becomes increasingly likely to spill over into developed markets including the U.S.

Given that the U.S. market is already struggling with high inflation and the looming threat of an economic recession (if it’s not here already) during a time of historically high stock valuations, it will be important to watch how events unfold across emerging markets in the coming months. For if the problem continues to spread, it could have a compounding effect in pushing stocks to the downside.

Be the first to comment