Last week, I discussed in “Recession Risks Tick Up” that while current data may not suggest a possibility of a recession was imminent, other “off the run” data didn’t agree.

“The problem with most of the current analysis, which suggests a “no recession” scenario, is based heavily on lagging economic data, which is highly subject to negative revisions. The stock market, however, is a strong leading indicator of investor expectations of growth over the next 12 months. Historically, stock market returns are typically favorable until about 6 months prior to the start of a recession.”

“The compilation of the data all suggests the risk of recession is markedly higher than what the media currently suggests. Yields and commodities are suggesting something quite different.”

In this particular case, while the market is suggesting there is an economic problem coming, we also discussed the impact of the “coronavirus,” or “COVID-19,” on the economy. Specifically, I stated:

“But it isn’t just China. It is also hitting two other economically important countries: Japan and South Korea, which will further stall exports and imports to the U.S.

Given that U.S. exporters have already been under pressure from the impact of the “trade war,” the current outbreak could lead to further deterioration of exports to and from China, South Korea, and Japan. This is not inconsequential as exports make up about 40% of corporate profits in the U.S. With economic growth already struggling to maintain 2% growth currently, the virus could shave between 1-1.5% off that number.

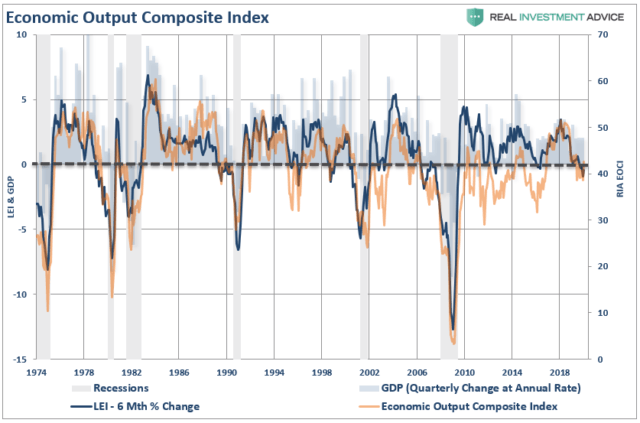

With our Economic Output Composite Indicator (EOCI) already at levels which has previously denoted recessions, the “timing” of the virus could have more serious consequences than currently expected by overzealous market investors.

(The EOCI is comprised of the Fed Regional Surveys, CFNAI, Chicago PMI, NFIB, LEI, and ISM Composites. The indicator is a broad measure of hard and soft data of the U.S. economy)”

“Given the current level of the index as compared to the 6-Month rate of change of the Leading Economic Index, there is a rising risk of a recessionary drag within the next 6 months.”

That analysis seemed to largely bypass the mainstream economists, and the Fed, who were focused on the “number of people getting sick,” rather than the economic disruption from the shutdown of the supply chain.

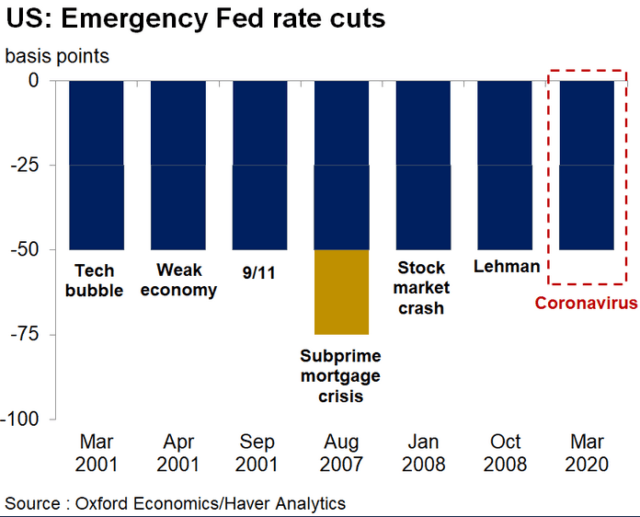

On Tuesday, the Federal Reserve shocked the markets with an “emergency rate cut” of 50 basis points. While the futures market had been predicting the Fed to cut rates at their next meeting on March 18th, the half-percent cut shocked equity markets as the Fed now seems more concerned about the economy than they previously acknowledged.

It is one thing for the Fed to cut rates to support economic growth. It is quite another for the Fed to slash rates by 50 basis points between meetings.

It smacks of “fear.”

Previously, such emergency rate cuts have not been done lightly, but in response to a bigger crisis which was simultaneously unfolding.

While we have spilled a good bit of digital ink as of late warning about the ramifications of COVID-19:

“Clearly, the ‘flu’ is a much bigger problem than COVID-19 in terms of the number of people getting sick. The difference, however, is that during ‘flu season,’ we don’t shut down airports, shipping, manufacturing, schools, etc. The negative impact on exports and imports, business investment, and potential consumer spending are all direct inputs into the GDP calculation and will be reflected in corporate earnings and profits.”

This is not a trivial matter.

“Nearly half of U.S. companies in China said they expect revenue to decrease this year if business can’t return to normal by the end of April, according to a survey conducted Feb. 17 to 20 by the American Chamber of Commerce in China, or AmCham, to which 169 member companies responded. One-fifth of respondents said 2020 revenue from China would decline more than 50% if the epidemic continues through Aug. 30..” – WSJ

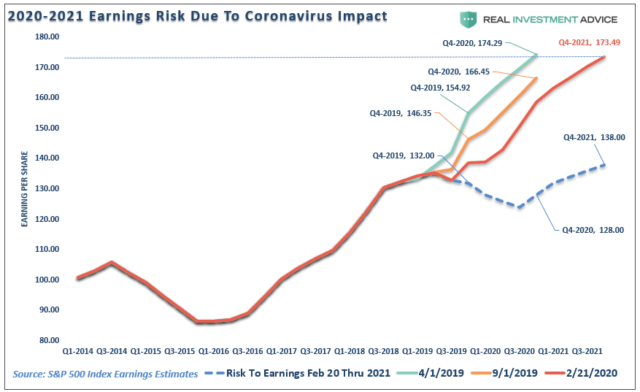

That drop in revenue, and ultimately earnings, has not yet been factored into earnings estimates. This is a point I made on Tuesday:

“More importantly, the earnings estimates have not been ratcheted down yet to account for the impact of the “shutdown” to the global supply chain. Once we adjust (dotted blue line) for a negative earnings environment in 2020, with a recovery in 2021, you can see just how far estimates will slide over the coming months. This will put downward pressure on stocks over the course of this year.”

It is quite possible even my estimates may still be too high.

While the markets have been largely dismissing the impact of the virus, the Fed’s “panic” move on Tuesday was confirming evidence that we are on the right track.

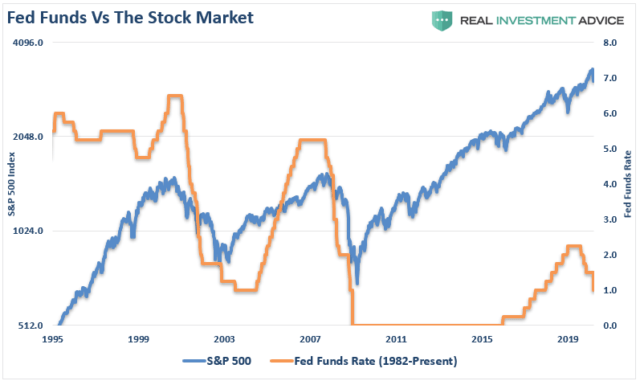

The market’s wild correction over the past two weeks also begins to align with the Fed’s previous rate-cutting cycles. While it initially appeared “this time was different,” as the market continued to rise due to the Fed’s flood of liquidity, the markets seem to be playing catch up to previous rate-cutting cycles. If the economic data begins to weaken markedly, we may will see an alignment with the previous starts of bear markets and recessions.

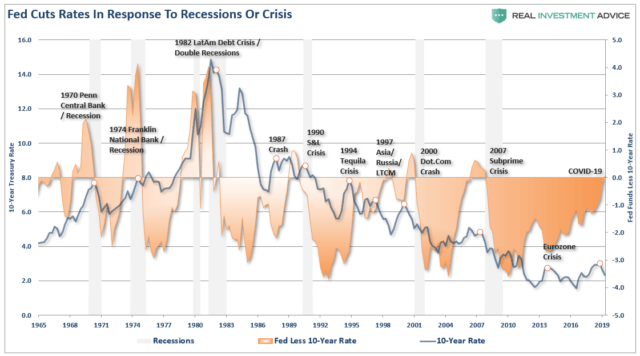

Of course, we need to add some context to the chart above. Historically, the reason the Fed cuts rates, and interest rates fall, is because the Fed has acted in response to a crisis, recession, or both. The chart below shows when there is an inversion between the Fed Funds rate, and the 10-year Treasury, it has been associated with recessionary onset. (This curve will invert when the Fed cuts rates further at their next meeting.)

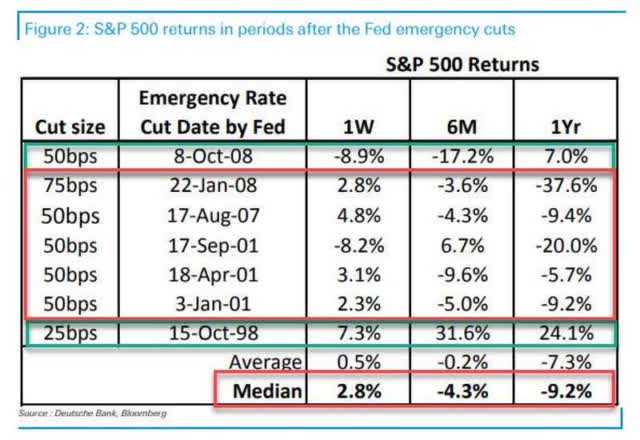

Not surprisingly, as suggested by the historical data above, the stock market has yielded a negative return a year after an emergency rate cut was initiated.

There is another risk the Fed may not be prepared for, an inflationary spike in prices. What could potentially impact the economy, and inflationary pressures, is the shutdown of the global supply chain which creates a lack of supply to meet immediate demand. Basic economics suggests this could lead to inflationary pressures as inventories become extremely lean, and products become unavailable. Even a short-term inflationary spike would put the Federal Reserve on the “wrong-side” of the trade, rendering the Fed’s monetary policies ineffective.

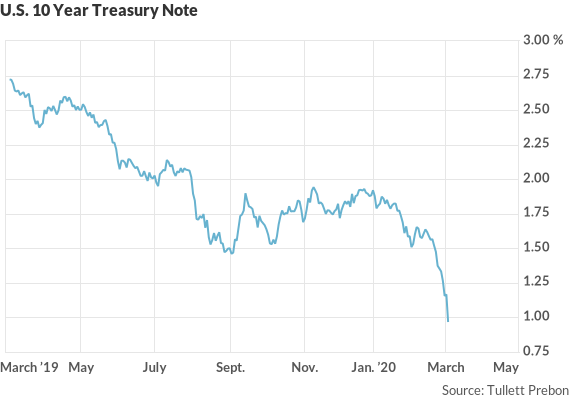

The rising recession risk is also being signaled by the collapse in the 10-year Treasury yield, a point which I have made repeatedly over the last several years in discussing why interest rates were headed toward zero.

“Outside of other events such as the S&L Crisis, Asian Contagion, Long-Term Capital Management, etc. which all drove money out of stocks and into bonds pushing rates lower, recessionary environments are especially prone at suppressing rates further. But, given the inflation of multiple asset bubbles, a credit-driven event that impacts the corporate bond market will drive rates to zero.

Furthermore, given rates are already negative in many parts of the world, which will likely be even more negative during a global recessionary environment, zero yields will still remain more attractive to foreign investors. This will be from both a potential capital appreciation perspective (expectations of negative rates in the U.S.) and the perceived safety and liquidity of the U.S. Treasury market.

Rates are ultimately directly impacted by the strength of economic growth and the demand for credit. While short-term dynamics may move rates, ultimately the fundamentals combined with the demand for safety and liquidity will be the ultimate arbiter.”

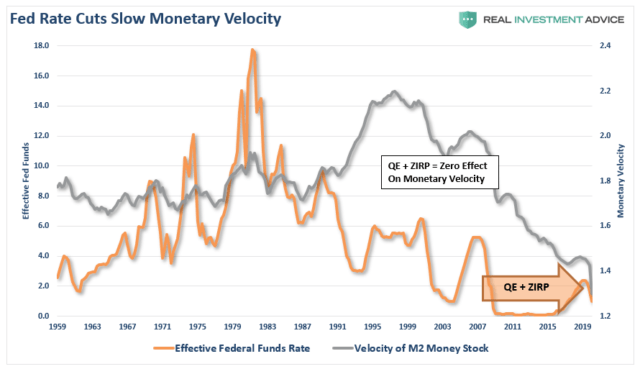

A chart of monetary velocity tells you there is a problem in the economy as lower interest rates fail to spark an uptick in the flow of money.

My friend Caroline Baum summed up the Fed’s primary problem given the issue of plunging rates:

“All of a sudden, the reality of revisiting the zero lower bound, which the Fed now refers to as the effective lower bound (ELB), is no longer off in the distance. It could be right around the corner.

And this at a time when Fed officials are still saying that the economy and monetary policy are ‘in a good place’ and the fundamentals are sound. So what do policymakers do when the good place deteriorates into something mediocre, and the fundamentals turn sour?

Forward guidance, which I like to call talk therapy? Large-scale asset purchases? Unfortunately, the Fed goes to war with the tools it has, not the tools it might want or wish to have.”

Unfortunately, the Fed is still misdiagnosing what ails the economy, and monetary policy is unlikely to change the outcome in the U.S.

The reasons are simple. You can’t cure a debt problem with more debt. Therefore, monetary interventions, and government spending, don’t create organic, sustainable, economic growth. Simply pulling forward future consumption through monetary policy continues to leave an ever-growing void in the future that must be filled.

There is already evidence that lower rates are not leading to expanding consumption, business investment, or economic activity. Furthermore, while QE may temporarily lift asset prices, the lack of economic growth, resulting in lower earnings growth, will eventually lead to a repricing of assets.

Furthermore, there is likely no help coming from fiscal policy, either. As Caroline noted:

“Fiscal policy measures, which entail tax cuts and government spending, will be difficult to enact in this highly charged political environment. There is little evidence that the Republicans and Democrats can put partisan differences aside to work together.”

Or, as Chuck Schumer said to Ben Bernanke just prior to the “financial crisis:”

“You’re the only game in town.”

The real concern for investors, and individuals, is the real economy.

We are likely experiencing more than just a “soft patch” currently despite the mainstream analysts’ rhetoric to the contrary. There is clearly something amiss within the economic landscape, even before the impact of COVID-19, and the ongoing decline of inflationary pressures longer term was already telling us just that.

The Fed already realizes they have a problem, as noted by Fed Chair Powell on Tuesday:

“A rate cut will not reduce the rate of infection. It won’t fix a broken supply chain. We get that.”

More importantly, this is no longer a domestic question, but rather a global one. Since every major central bank is now engaged in a coordinated infusion of liquidity, fighting slowing economic growth, a rising level of negative yields, and a spreading virus shutting down economic activity, it is “all hands on deck.”

The Federal Reserve is currently betting on a “one trick pony” which is that by increasing the “wealth effect,” it will ultimately lead to a return of consumer confidence, and mitigate the effect of a global contagion.

Unfortunately, there mounting evidence it may not work.

Editor’s Note: The summary bullets for this article were chosen by Seeking Alpha editors.

Be the first to comment