RistoArnaudov/E+ via Getty Images

Adams Resources & Energy, Inc. (NYSE:AE) is an oil and liquids transporter with operations in the U.S. Gulf Coast and Southeast. The company presented record earnings in 2021 and 2022 based on increased oil production in Texas, and trades at a TTM P/E ratio of 10.

Its markets are commoditized and affected by oil production in the Gulf Coast, which in turn is indirectly affected by oil prices. Although Adams Resources has been producing more earnings and cash flows on an adjusted basis for the past decade than its GAAP accounting indicates, I believe its historical earnings power does not justify its current valuation.

Further, the company’s largest shareholder has announced its intentions to sell its stake, as much as 40% of the company’s share base, which could increase volatility in the following months.

In this article, I also discuss the company’s questionable past capital allocation decisions, future perspectives of its markets, and latest financials.

Note: Unless otherwise indicated, all information has been obtained from AE’s filings with the SEC.

Industry characteristics

Adams Resources currently operates in three midstream markets related to the Gulf Coast’s oil industry. These three businesses all operate around transporting hydrocarbon products.

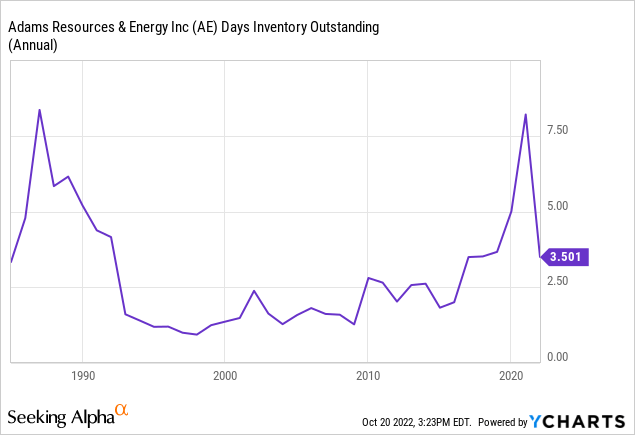

The company’s biggest segment, called marketing, buys crude oil directly from producers in the Gulf Coast, stores it and transports it to refiners in the Southwest. The company’s business is to provide a simplified interface to both producers and purchasers of crude oil. It deals with several producers that can sell to a single entity instead of finding different purchasers. The same happens with refiners. The company also controls injection points connected to the oil grid, storage tanks in different points in Texas and Louisiana, and a fleet of trucks. Although the company calls this segment marketing, and records the crude oil as both revenue and CoGS (therefore generating extremely low margins and accounting noise), it does not trade the product per se, and is not exposed directly to oil prices. Most crude oil is in and out of the company’s balance sheet in three days on average.

The marketing business is commoditized in the sense that the company’s service cannot be substantially differentiated from others at the eyes of purchasers and sellers. However, the company may build long standing relationships that benefit its clients by simplifying selling and purchasing processes. In general, though, AE is unable to affect demand and prices for its services, which are affected by oil production in the Gulf region. When oil production increases, transported quantities rise, as well as the slippage that can be obtained from the service. The opposite happens during depressed production periods.

The second segment is liquids transportation. Adams Resources has a fleet of 300 trucks and 800 trailers, plus terminal stations in 10 Southwest states. In this case, the company does not purchase the liquids but rather is paid only for the service of transporting them to different points in the U.S. and Canada. The dynamics of this business are similar to those of the marketing segment. AE can build relationships that help the company keep a certain level of business volume, but prices are determined by the balance of trucking services demand and supply.

Finally, Adams Resources acquired a loss generating pipeline traversing Victoria and Cuero counties in Texas, that ends in Victoria Port, an inland port close to the exporting terminals in Corpus Christi. The pipeline has been operating at less than 10% capacity. Again, this business is affected by relative demand, with the difference that supply is much more fixed. If demand grows, prices will be more sustainable than in the other two segments, because supply cannot be increased in the short to medium term.

Summing up, Adams Resources’ businesses share two characteristics. First, they are all related to oil production in the Gulf Coast. Second, although AE can build some volume continuity and business relations, it has absolutely no pricing power. The two characteristics move business in the same direction: when production increases, transportation supply becomes tight and prices and volumes rise; and vice versa. This is a classical characteristic of a commoditized market.

Adjusting the accounting

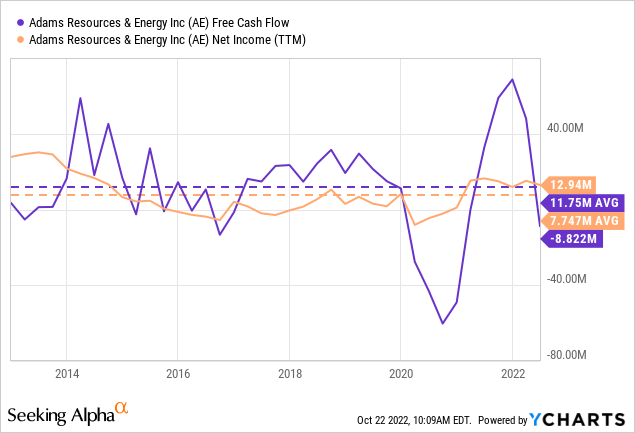

The marketing segment generates a lot of noise in Adams Resources’ accounting that makes understanding the business’ profitability more difficult. To put an example, compare net income and free cash flow (“FCF”) below for the past decade.

Most noise arises from Adams Resources’ recognition of the marketed oil as an inventory.

To begin with, this means that Adams Resources recognizes transported crude oil in revenue and in CoGS. The first effect is that AE’s margins are minimal. Gross margins have barely averaged 1% for the past decade. This provides the erroneous idea that AE’s business is extremely sensitive to price variations, and barely competitive. This practice, coupled with mixing oil “costs” with the service costs, like fuel and labor, complicates understanding the segment’s true profitability dynamics.

The second noise issue is the recognition of fair value gains and losses on AE’s inventories. As I mentioned, AE has no real exposition to inventory price variation, because on average it only holds oil for three days and it can probably fix prices for that short period. However, AE’s pipelines, injectors and storages require a minimum level of oil consistently in the system. This is recognized as some sort of permanent inventory, which value changes with variations in oil prices. Because AE’s business is marginal compared to the prices of the oil it transports, variations in this permanent inventory can have bigger effects in the income statement than the whole operations. But the reader should be aware that AE has no exposition at all to those price changes. It does not make or lose money because that inventory is never bought or sold. Rather, it is a permanent fixture the productive process.

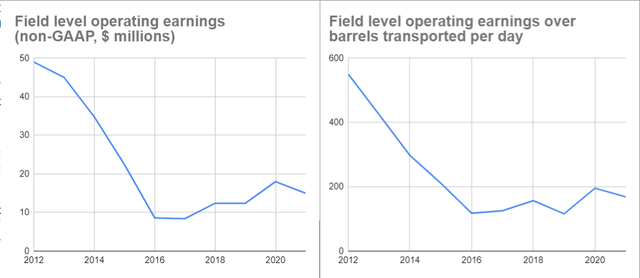

Fortunately, AE reports a non-GAAP financial measure called field level operating profits, that removes the inventory revaluation effect. Below are both the compiled figures for total business profitability and profitability per barrel. It is noticeable how both total profitability and unit profitability fall.

AE’s Field level operating earnings and FLOE over barrels transported per day. Non-GAAP financial measure (Own, based on AE’s filings with the SEC)

What happened? Management’s discussion from FY16’s 10-K explains it better than I can:

Previously a key factor in unit margins was the value difference between the value of crude oil supply in the mid-continent region of the United States versus crude oil supply costs in the eastern region of the United States. The Company was able to capture some of this value difference by shipping crude oil from the Texas Gulf Coast to points east. Due to competitive pressures during 2014, the opportunities for the Company to capture this location based unit value difference evaporated which reduced earnings.

Can we expect an increase in unit prices? Probably not, given that the oil boom in the Gulf Coast generated by shale and tight sands has already been in full fledge for almost a decade. Infrastructure has been built, and prices have stabilized.

Some questionable capital allocation decisions

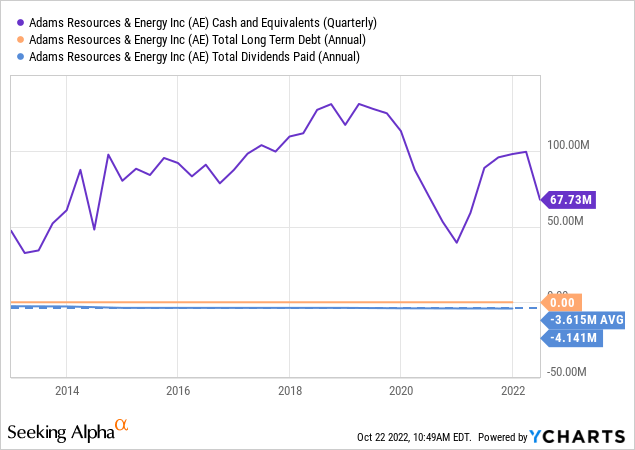

In general, I believe AE’s capital allocation policies have been very conservative. The company has paid a steady dividend, at the same time that it accumulated a gigantic cash reserve, all while avoiding any kind of debt.

The company has done some acquisitions of trucking companies that can be considered a form of expensive PP&E investment. AE paid a premium for the “client relations” of these companies, but I doubt those relations are either stable or significant. In total, two trucking companies, EH Transport (May 2019) and CTL (June 2020) were acquired for a price of $15.5 million, a $5.5 million premium over the tangible assets acquired.

The Victoria pipeline was acquired for its asset value, determined at a cost of $20 million. It is difficult to determine if cost was a good measure of value, given that the pipeline operates at a loss, well below capacity. More on this later.

AE also has a series of failed incursions in related business. The company impaired and liquidated its exploration business between 2012 and 2015, registering accrual losses of almost $40 million in the period. It also impaired a $2.5 million investment in a completely unrelated healthcare tech company called VestaCare.

Latest acquisitions for Adams Resources

In August, AE announced that it had reached an agreement to purchase two companies, Firebird and Phoenix, for $32 million, or 50% of the company’s cash vault as of 2Q22. The company has not provided financial statements for the acquired companies but commented that the acquisitions were expected to increase the company’s adjusted cash flows by 30% (without a time frame).

Firebird Bulk-Carriers is in the same business as the marketing segment, carrying crude oil. The company has approximately 100 tractors and operates around Humble, Texas (north of Houston). Phoenix Oil purchases, recycles and sells used hydrocarbon products like naphtha, heavy oils, diesel, etc.

These are the company’s largest acquisitions so far. The purchase price was not allocated to each company yet, but it seems expensive. For one thing, in 2020 AE paid $9 million for CTL (including $3 million for intangible assets) and obtained 163 tractors.

Future earnings power

We have already evaluated Adams Resources’ main profitability engine, the marketing segment. A few years after the oil boom in the Gulf Coast began, prices decreased and stabilized. The increase in oil prices and production after 2020 did not change this reality.

Therefore, we can consider field level operating profits (excluding fair value accounting for inventories) for this segment of between $12.5 million and $20 million. This does not depend on transported quantities, but rather short term supply and demand imbalances.

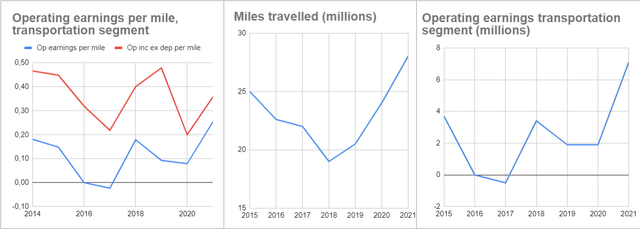

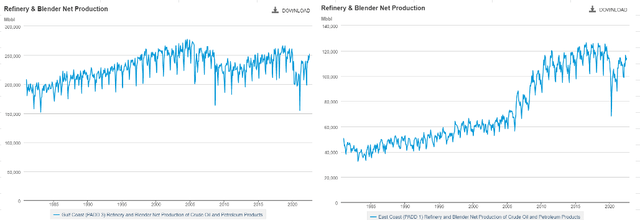

The transportation segment is much more affected by volumes because of fixed investments and depreciation, but also because prices seem to be related with miles traveled (compare the red line in first chart below with miles traveled in the second chart). I could not find the reasons behind the fall in miles traveled between 2015 and 2019. The EIA does not show a fall in liquids production neither in the Gulf Coast (left chart, second row below) nor the East Coast (right chart, second row below). Could it be that the increase in refining in the East Coast after 2005 was followed by a period of over-investment in transport capacity that only became patent several years later? In any case, the transportation segment’s earnings range between nil and $6 million.

Operating earnings for the transportation segment, miles travelled and operating earnings per mile travelled (Own, based on AE’s filings with the SEC.) Total refining production, Gulf Coast region (left), East Coast region (right) (EIA)

Adding these two segments provides an operating profit before corporate costs of between $12.5 million and $26 million. What determines what end of the range the company operates in? The balance between oil and liquids production in the Gulf Coast and the East Coast and supply of transportation services. In my opinion, the current dynamics might be sustainable from the demand standpoint (the U.S. can keep producing oil and liquids at the same rate), but the supply side will tend to destroy prices. The reason is that these segments require trucks, truckers and stations. It is not extremely difficult to bring new capacity to the market.

Therefore, in my opinion the most optimistic scenario for long-term average profitability is $19.5 million. Of course, this is an average, composed of significant volatility. The riskiness associated with this forecast is high.

Before commenting on costs, a comment should be made on management’s ability. In general, if a company can operate profitably in both ends of a commoditized market’s cycle, it is a great signal of management’s ability to control costs and operate efficiently. At least at the segment level (before SG&A) this is true for both the marketing and the transportation segments of AE. It makes a world of difference for a commodity product company if it can survive profitably or at least barely profitably in the downward portion of the cycle.

Then we have to add two sources of costs: the pipeline segment and SG&A costs. The pipeline segment is generating operating, cash-based losses. As of 1H22, the segment has generated $1.6 million in operating losses. Only $500 thousand can be explained by depreciation, therefore the rest are cash losses. In fact, the pipeline is generating more losses the more it transports, as higher losses for 2Q22 despite higher throughput indicate. Of course, the pipeline operates at 15% capacity as of 2Q22. If the company is able to increase utilization, it is probable that economies of scale will also improve its profitability.

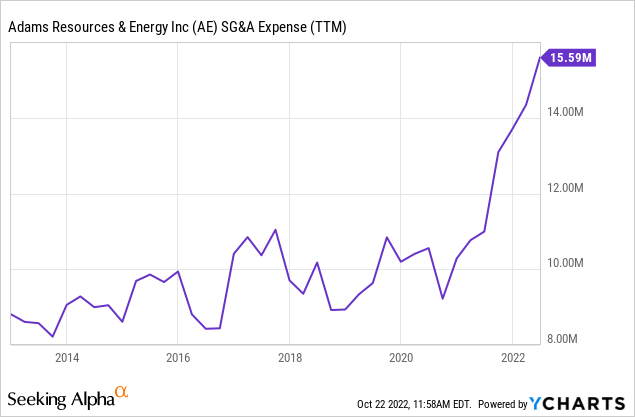

Finally SG&A is an important issue. For years, Adams Resources had maintained a consistent SG&A expense figure of $10 million. However, last year that figure jumped to $15 million. The company’s management did not provide color on that increase or its temporality on its MD&A and does not hold earning calls. If we take the MD&A’s comment that SG&A increased primarily due to higher salaries and wages and related personnel costs, insurance costs and outside service costs, then the change has to be considered permanent. In fact, for both 1Q22 and 2Q22 SG&A has continued rising on a YoY and QoQ basis.

Price considerations and conclusions

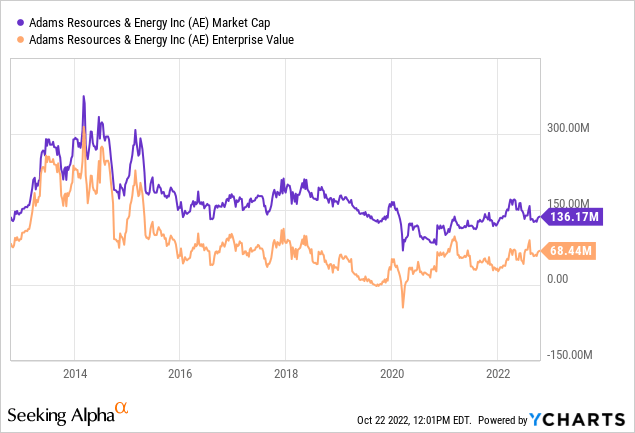

Before considering the investment merits of AE’s stock, we need to consider what is the company’s true price. With a significant cash holding and negligible liabilities, the company’s EV is much lower than its market cap. As can be seen below, that gap has been there for at least 6 years. The company’s cash balance will be reduced by $32 million after the acquisition of Phoenix and Firebird announced in August. That would elevate EV to $100 million, closing the gap a little bit.

In my opinion, EV can be considered if the company had a plan to repurchase and cancel shares, distribute extraordinary dividends, or if the investor was actually able to acquire the whole company. The first two possibilities have not been announced by AE, and the company has kept that enormous cash balance for years. The third possibility depends on the reader’s funds.

Therefore, I prefer to consider the market cap, because it better reflects the returns that are available for the individual shareholder, unless there is a purchase program or special-dividend announced.

With that in mind, even with the super-optimistic, and in my opinion unrealistic, outlook, of $26 million in operating profits before SG&A, and a return to previous SG&A levels, AE would still not justify its current stock price. If we subtract $10 million SG&A from the $26 million operating profit, and then another $4 million for the operating losses of the pipeline project, we arrive at $12 million pre tax profits. That, in turn, translates into $9 million in net income, or a P/E ratio of 15. The reader should remember that this is the absolutely most optimistic scenario.

What about a more realistic, albeit still optimistic scenario of $19.5 million from the two profitable segments? Even considering low SG&A ($10 million), the net profit calculation comes to $4 million a year.

Even if the recent acquisitions could deliver on their promise of 30% increase in adjusted cash flows, the figures above would not justify the current stock price. Instead of $9 and $4 million for the super optimistic and relatively optimistic scenarios, the company could generate $15 and $8.5 million respectively.

Finally, in May, the company’s largest shareholder group announced its decision to sell its 40% stake in the company in a public or private fashion. This could add volatility to the stock’s price, either up or down, depending on the market’s perception of how the sale is conducted.

In my opinion, then, AE is not a buy at current prices, and a significant discount should be asked. In the future, the most important factors to consider will be the change in control, financial information of the recent acquisitions, and the behavior of SG&A costs.

Be the first to comment