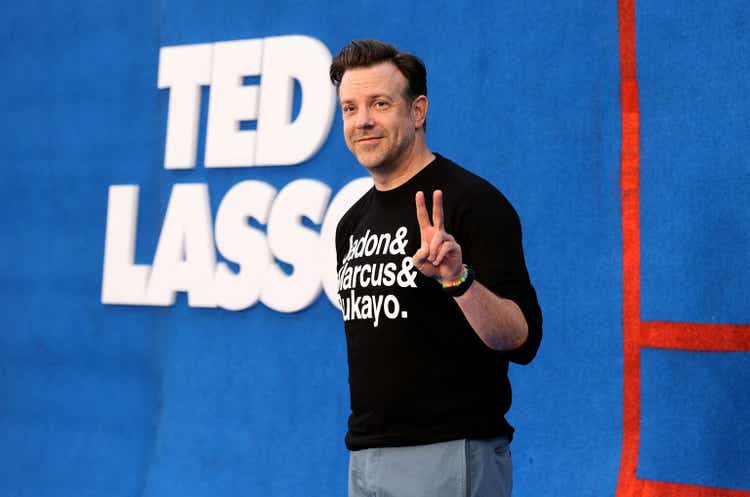

Ted Lasso holds the key to valuing Warner Bros. Discovery’s stock Amy Sussman/Getty Images Entertainment

Investors in Warner Bros. Discovery, Inc. (NASDAQ:WBD) stock have had an eventful year to say the least. After the company completed its merger with Warner Media, they had to persevere all the selling from AT&T Inc. (T) shareholders, then they had to face the fact the company would miss its free cash flow guidance. Add to that an uncompromising Federal Reserve, and it’s no wonder the stock is down almost 45% year-to-date.

The majority of the negative commentary surrounding the company is on whether it can navigate chord-cutting to pay down its debt (which stands at 5x EBITDA).

Wells Fargo analyst Steven Cahall, for example, said that cord cutting was speeding up, and that the phenomenon will pose a challenge for WBD given cable is about 20% of revenue.

Moffett Nathanson analyst Robert Fishman, for his part, said that the company’s latest results showed how reliant it is on cable revenues. He added that:

The risk is that accelerating cord-cutting and linear ad weakness could further pressure networks’ profitability, which may offset any DTC improvement after expected peak losses in 2022.

WBD has navigated changes in distribution before

Just nine years ago, Time Warner (which is now part of WBD) made 12% of its revenue from selling magazines. Today, that number is 0% and the company has more revenue. More infamously, a big chunk of the company’s revenue in 2000 came from Internet dial-up subscriptions. That business is completely gone today as well.

The lesson here is quite clear; History repeatedly shows that valuing media companies based on their distribution capabilities would lead to grave underestimation of their potential. Imagine if investors in the 1920s thought of Disney (DIS) as just a movie studio, or in the 1970s that DC and Marvel were simply comic book publishing businesses. Such propositions seems ludicrous today with perfect hindsight, but analysts could be making a similar mistake today when they (rightly) point out that WBD is currently overly-reliant on cable revenues.

Warner Bros. itself started out as a movie theater business. The company then morphed into a movie studio, and when TV came along they started producing TV shows (including mega hits like Friends). It also founded what is now Warner Music Group Corp. (WMG), and this year they published two of the three best-selling video games. Pinning them as a movie studio would have mischaracterized the company, and labelling them today merely as a cable company could be a similar error in judgement.

The question becomes what makes a media company able to navigate these shifts in distribution? Why did Time Inc. drift into insignificance while Warner Bros. continued to grow its revenue and cultural importance?

The answer in my opinion is intellectual property. Warner Bros. Discovery is not a cable company, it’s an IP company. The issue for most investors is how can we value any given company’s IP?

Warner Bros. Discovery is worth a lot more based on the relief-from-royalty accounting method

Instead of assigning WBD a cable-company multiple (given that’s where the majority of its cash will come from), a better method is to try and come up with an educated guess as to the value of its library and IP.

The Relief from Royalty accounting method could be a useful guide to investors in that regard. It tries to value an intangible asset by discounting hypothetical royalty payments in the future to their present value. It is basically the sum another company like Netflix (NFLX) and Amazon.com Inc. (AMZN) would pay WBD if they were to buy all of its past and future content net of the cost to produce it, discounted it to the present.

How much would Netflix pay WBD to have The House of the Dragon exclusively on its platform? Investors can use similar licensing deals to try and come up with an educated guess for the price, then repeat the process for the entire WBD library. Then look at market deals related to future content, to try and figure out how much would WBD be making on those. Recent announcements like the one made by Netflix on licensing Sony (SONY, OTCPK:SNEJF) movies for example can be a good starting point for investors. Applying this process is beyond the scope of the article, given the length it would take to do so.

For WBD investors, the question they need to ask is how much can the company make licensing past and future content, discounted by an appropriate discount rate?

One of the challenges in using this method is that there isn’t a lot of transparency over the details of licensing deals.

To try and overcome these complications, we can just ask one straightforward, question; would Netflix be willing to swap the $17 billion it spends a year on content to get all of WBD’s old library and all of its new shows and movies?

If the answer is yes (which is what I would lean towards) we can get a rough estimate of how much WBD would make conservatively in that scenario. Assuming the company will spend an extravagant $200 million (for both production and marketing) a movie on the 20 movies it plans to release each year, the total spending will amount to $4 billion a year. As for TV shows, the company is releasing 46 scripted shows in 2022. At a respectable $80 million a show, this brings TV spend to $3.7 billion a year and total content spend to $7.7 billion annually. For context, The Batman and House of The Dragon cost $200 million and more than $150 million, respectively.

Subtracting the cost from Netflix’s content spend of $17 billion and theatrical revenue of $1.75 billion (note that the theatrical revenue assumed implies the company is losing money on its movie theater business), WBD’s operating profit would be in the region of $11 billion, or $8.7 billion after tax.

I’ll also assume that the cost Netflix pays will grow above the inflation target for developed economies of 2% (a growth rate of 4%), given the enduring value of high-quality IP. With a discount rate of 10%. The value of the IP based on those factors would be $66.2 a share, or $42.1 a share after subtracting debt. Note that the debt wasn’t really used to finance the library, but only to buy Warner Media from AT&T Inc. (T). So it isn’t necessarily part of the costs of creating the content.

The process is clearly subjective, as each investor will end up with their own number to the value of the content. What matters in that case is having a large margin of safety.

Risks

In 2013, Netflix’s then COO Ted Sarandos said the company’s aim was:

To become HBO faster than HBO can become us.

In that respect, the method used in this article might be a useful guide for investors looking to value the IP, but it’s unlikely to be practical. Surely Netflix would like to license the House of The Dragon to stream exclusively on its platform, but companies also realize the financial importance of building their own franchises and could resist the temptation to rely mainly on other studios’ content.

Also, the licensing rates and current content spend levels could be reflective of the land-grab phase of the streaming market. Meaning that the assumed value of the content could be inflated compared to a more competitively-defined, oligopolistic streaming market.

And just because a library is valuable today, doesn’t mean that a management team can’t dilute its value. Although I consider it a remote possibility, there is no guarantee WBD management won’t make some missteps that dilutes the value of its IP.

Furthermore, while I consider scripted-media IP to be an intangible asset with an indefinite life (meaning it shouldn’t be amortized), there is no doubt that parts of that IP get impaired every year. There is no guarantee that the current creators in the company can add more valuable IP to the library faster than older properties are impaired, meaning that the company’s IP would diminish over time.

Conclusion

WBD’s woes seems to stem from a worry over whether the company will be able to adapt to the new mode of distribution. While history shows that investing in media is not for the faint of heart, it also shows that companies with durable IP like Warner Bros. Discovery have always been able to pivot when distribution shifts. Investors might be better served thinking how much WBD’s IP is worth to others, rather than fixate on short-term cable revenues. But investors should also keep an eye on whether management is working on enhancing the value of the company’s IP or if they are destroying it, given that will be the main driver of returns.

Be the first to comment