caio acquesta

Ultrapar Participacoes (NYSE:NYSE:UGP) is a Brazilian conglomerate with leading positions in service stations, bottled LPG and hydrocarbon liquid port facilities.

Back in January I wrote an article with a hold rating for UGP. Since then, the stock has returned 20%. In that article I questioned UGP’s excessive financial leverage. I also commented on the difficulty of determining UGP’s long term profitability while the company was divesting two of its segments.

In this review I find that UGP has concluded its most important divestment, for about $1.3 billion, using half the proceeds to reduce its debts. The company is also about to close its second, smaller divestment, for $140 million.

My opinion is still that the company’s share price is high. There are two main reasons. First, the company cannot earn more on its assets than what it pays on its debt. This could be solved by deleveraging. Second, its businesses are difficult to defend from competitive forces, are cyclical and have bad long term perspectives.

Note: Unless otherwise stated, all information has been obtained from UGP’s filings with the SEC.

UGP’s divestments and current segments

Since I wrote an article on UGP in January, the company has posted its 20-F annual report for FY21, and quarterly reports for 1Q22 and 2Q22.

These months have brought a few changes in the company and in its environment: the company divested one important segment; Brazil is growing fast; hydrocarbon prices soared; and the country’s interest rate is back to positive real territory.

To begin with, UGP had announced in 2021 its decision to divest both Oxiteno and Extrafarma, two segments unrelated to the company’s core businesses.

Oxiteno is a profitable chemical manufacturer. In FY21, Oxiteno generated almost $50 million in net income. The segment was sold to a chemical conglomerate for about $1.4 billion, with the transaction concluding in April 2022.

Extrafarma is an unprofitable pharmacy retailer. This segment has generated significant impairment losses for UGP, which sold it for about $140 million. The transaction has been approved by regulators but is still pending payment.

In my previous article, I commented that UGP should use some of the proceeds from the divestments to repay debts. It is good to see that the company has done so. UGP launched a tender offer for some of its dollar denominated debt, absorbing about $600 million. The rest has not been used for other purposes yet, currently strengthening the company’s cash position.

After the divestments, UGP has businesses in three major segments.

The company participates in gas stations and downstream fuel commercialization through its brand Ipiranga. UGP controls 18% of the light-vehicle fuel market through Ipiranga. This positions the company as the third player in the segment. Ipiranga is the main profit center of the company, generating triple the operating profits of the other two segments combined in 1H22.

UGP also participates in bottled LPG through Ultragaz, holding 24% of the market. Given that Brazil is a warm country, its consumption of natural gas is limited to cooking and to industrial and commercial uses. In many cases, these uses do not justify the investment to provide natural gas by pipeline. Gas is supplied in bulk or retail bottles by LPG distributors like Ultragaz.

Finally, UGP participates in liquid hydrocarbon port storage and logistics through Ultracargo. The company holds permits in several Brazilian ports to operate tanks to store exports and imports of hydrocarbon liquids.

Brazil’s growth and UGP’s cyclical businesses

A second development has been Brazil’s return to growth in 2021, but mostly in 2022. The boom in commodity prices has been a windfall for the country.

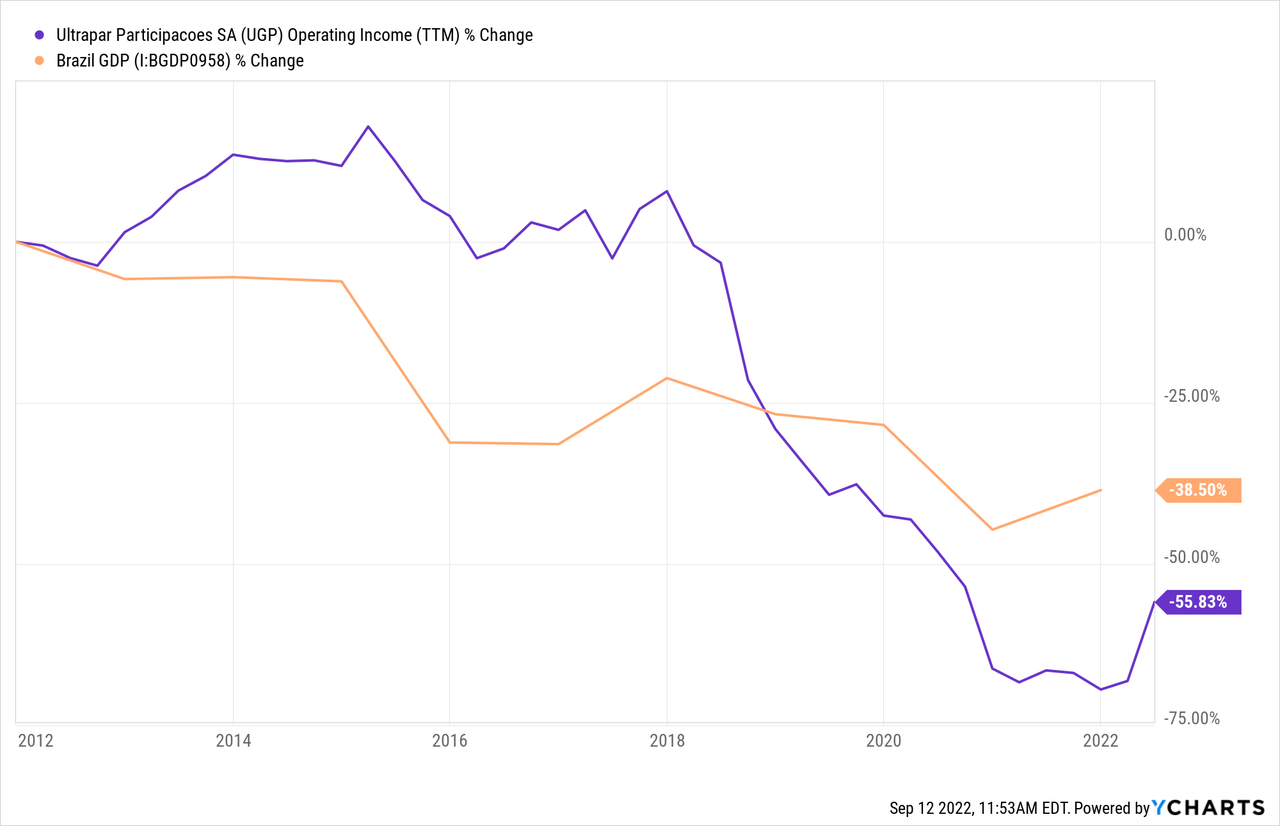

This is important for two reasons. First, Brazil passed through a “lost decade” in the 2010s, losing almost 50% of its GDP in between 2011 and 2020. Second, as the chart below shows, UGP’s profits are correlated to the country’s economy.

Brazil’s growth has been positive for UGP’s operations. On a restated basis, eliminating Oxiteno’s and Extrafarma’s entries, the company has posted 40% higher revenues, 50% higher gross profits and 70% higher operating income for 1H22 compared to 1H21.

Other factors help in posting those impressive growth figures. First, during 1H21 the pandemic was still affecting some markets, for example transportation, and consequently, fuel consumption. Second, the prices of hydrocarbons have moved up significantly, and Brazil’s Petrobras follows an international peg policy. With fuel consumption being relatively inelastic, price increases translate into revenue increases.

At this point it is convenient to analyze the competitive characteristics of UGP’s businesses. The common characteristic between the three is that they provide very little room for moat building, and are prone to profitability-destroying competition.

Starting with service stations, UGP’s main profitability center, they offer a commodity that can be easily compared by customers. It is true that some customers may develop some loyalty to a brand, but only as long as the price difference with other brands is not substantial.

The same is true for bottled LPG. Retail customers, who make two thirds of Ultragaz’s revenues, can easily change between providers if they notice a significant difference in price. Bulk customers are different, because Ultragaz installs tanks on their facilities, making switching between providers costly.

Finally, liquids storage and logistics is the more protected segment, given that it is based on permissions granted by the port authorities. However, these authorities also regulate pricing. This cancels part of the profitability that could be extracted from the relative scarcity.

In the three cases, the business cycle affects these segments. In the case of service stations, although fuel consumption is relatively price inelastic in the short term, it can be quite income elastic. If the economy is booming more cars and trucks will be purchased, pushing for fuel demand. If fuel demand or exports are increased, the storage segment will also increase business. In the case of LPG, the situation is not very different. Many Brazilians still have low incomes. This makes LPG an income elastic product.

Finally, all of the segments are exposed to transition risk. The most exposed is LPG, because it cannot be converted and because customers may change their appliances to electric, eliminating most of the need for the product. In the case of service stations, as more cars transition to electric energy, the stations could be transformed to electric charging, albeit at significant capital costs.

Brazil’s interest rates and UGP’s indebtedness

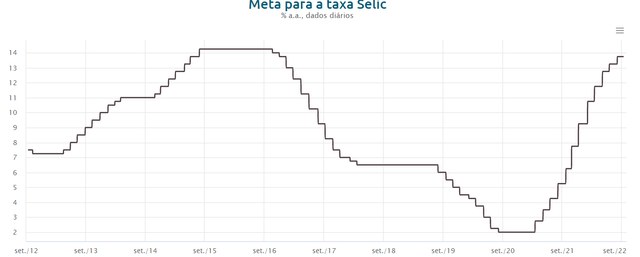

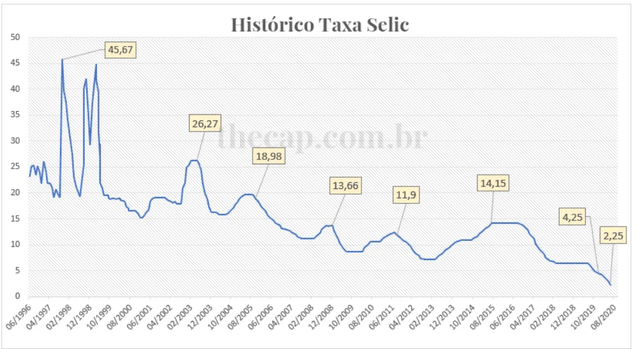

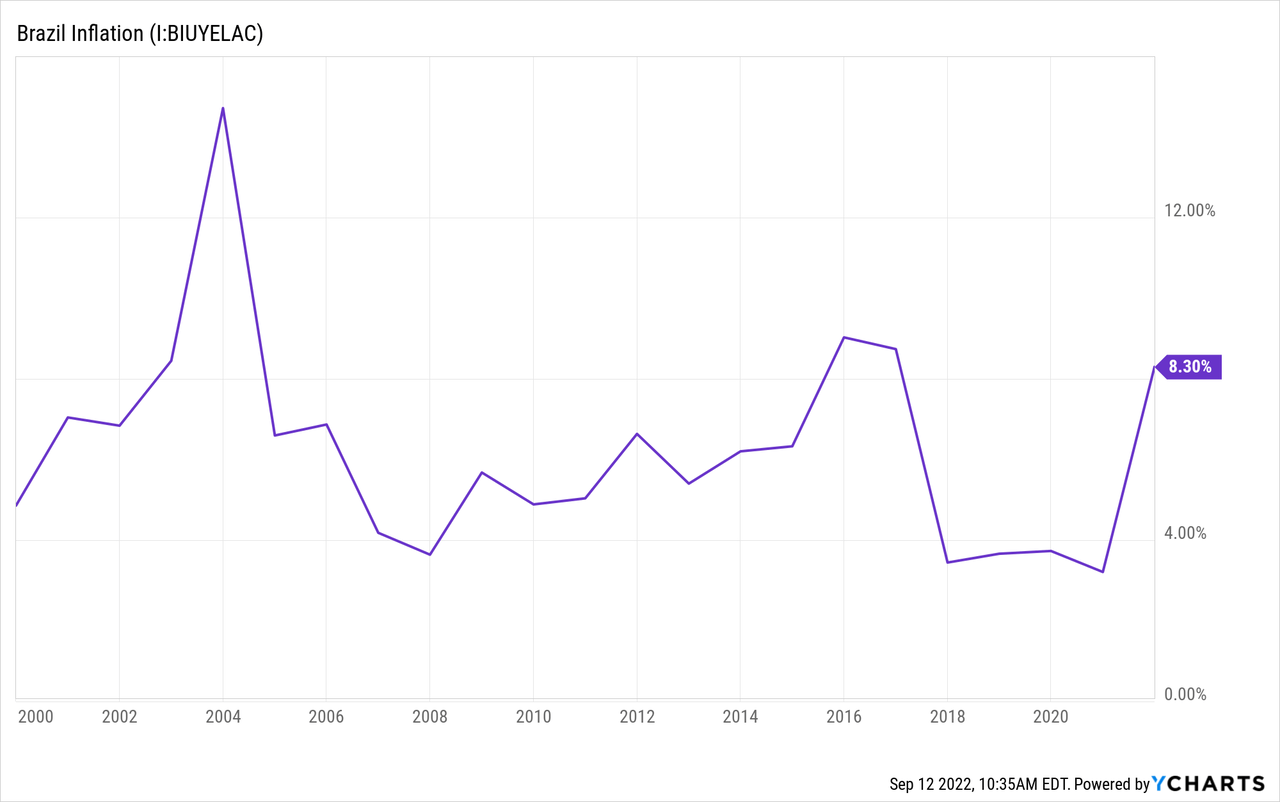

Finally, after a strange period of emergency caused by the pandemic, Brazil’s interest rates have moved back to positive real territory. The charts for the Selic rate (the prime lending rate in Brazil), posted by Brazil’s Central Bank and by The Capital Advisor, show that the prime rate has usually been nominally high, albeit decreasing. Coupling this data with Brazil’s inflation rate (third chart) shows that Brazil has usually had positive real rates.

Selic (BCB lending rate) (Brazil’s Central Bank (BCB))

Historic Selic rate (Brazil’s BCB lending rate) (The Capital Advisor Brazil)

Positive real rates are great for lenders, but they are terrible for borrowers. This development is problematic because after paying $600 million in debts using Oxiteno’s sale proceeds, UGP still owes about R$12 billion (~$2.5 billion), which yields variable interest tied to Brazil’s prime rate.

UGP still owes about $1 billion (~R$5 billion) in dollar denominated notes and loans maturing between 2026 and 2029. The company has swaps in place to convert interest payments (not the principals) from a fixed 5% in dollars to a variable CDI rate. CDI is the interbank deposit rate, which follows Brazil’s Central Bank prime rate quite closely.

The company also owes about R$7.5 billion in reals denominated financing. These debts mature mostly after 2026. They all yield variable rates tied to the CDI.

UGP likely cannot earn its cost of debt

A simple rule of thumb for debt is that it is beneficial to profitability if its cost is lower than what can be earned with the assets financed by that debt.

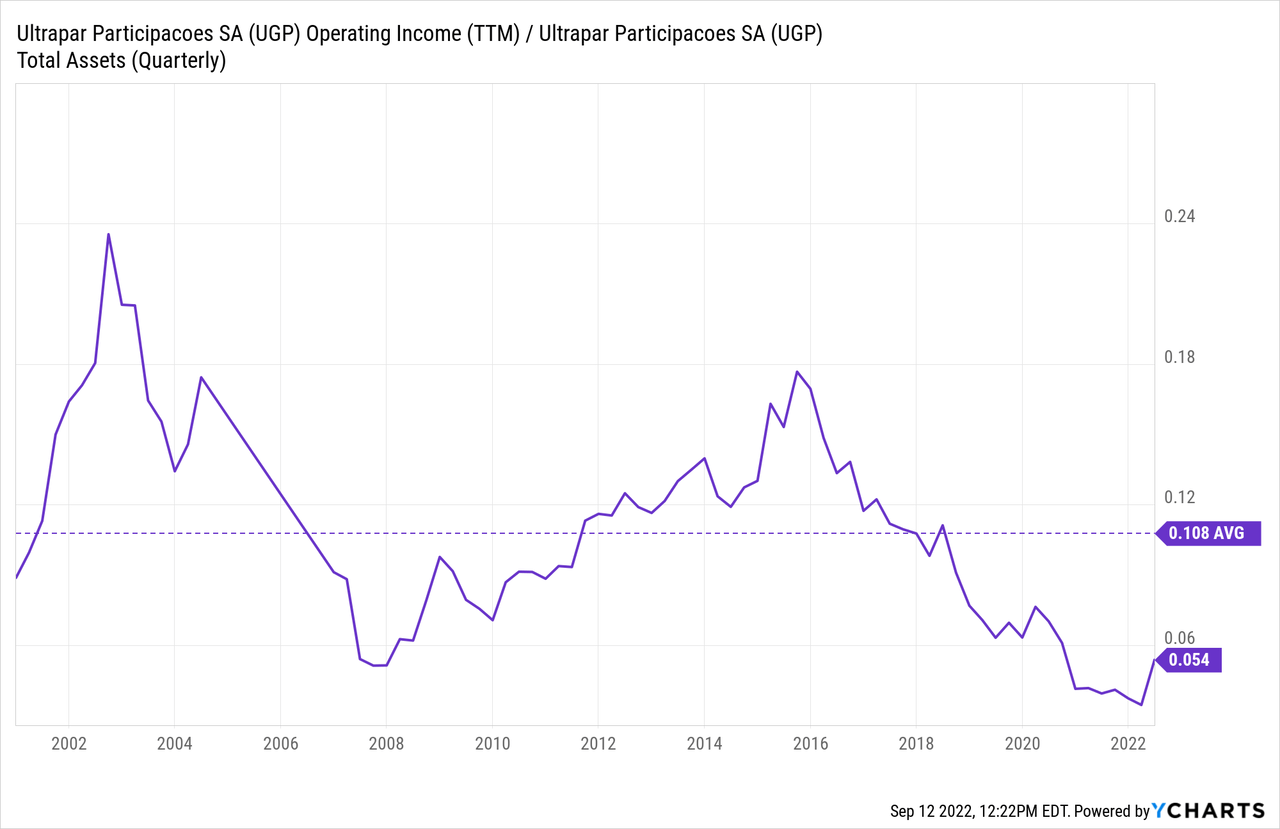

In order to calculate how much does UGP produce on its assets I use the ratio of operating income to total assets. This is more accurate than ROA because ROA is net income over assets, meaning that debt has already been paid.

As the chart above shows, UGP’s asset profitability moves in line with the Brazilian business cycle. This has been commented on already.

The problem is that averaging the valleys and tops of the cycles yields a return of 10%. Compare that with lending rates way above 10% for most of the past two decades, and Brazilian inflation generally below 10%.

My take from this is that Brazil is not a great country to be a borrower but rather to be a lender. UGP could earn a higher average return across the cycle by paying back debts.

Assumptions behind UGP’s stock price

Comparing UGP’s current stock price with the unadjusted data from FY21 and the first two quarters of 2022 is incorrect, because these include profitability from the already sold Oxiteno and Extrafarma.

In 1H22, the hydrocarbon related segments generated R$1.4 billion in operating income. The bulk of this operating income was generated by Ipiranga (the service stations), with R$900 million.

As we commented, the environment has been positive for these segments: Brazil is growing, which fuels demand, and prices have been increasing, which in turn increases revenue as well. Last year, in a more recessive context, the segments generated R$2 billion in operating income for the whole year.

We can invert the process and find out what is the necessary operating income to justify the current stock price.

We start with a current market cap of $2.8 billion ~ R$14 billion. If we ask for a PE of 10, that would translate to R$1.4 billion in yearly net income. A PE of 10 is probably high, because the company’s segments are mature and cyclical. The earnings yield should be higher, and consequently the PE lower.

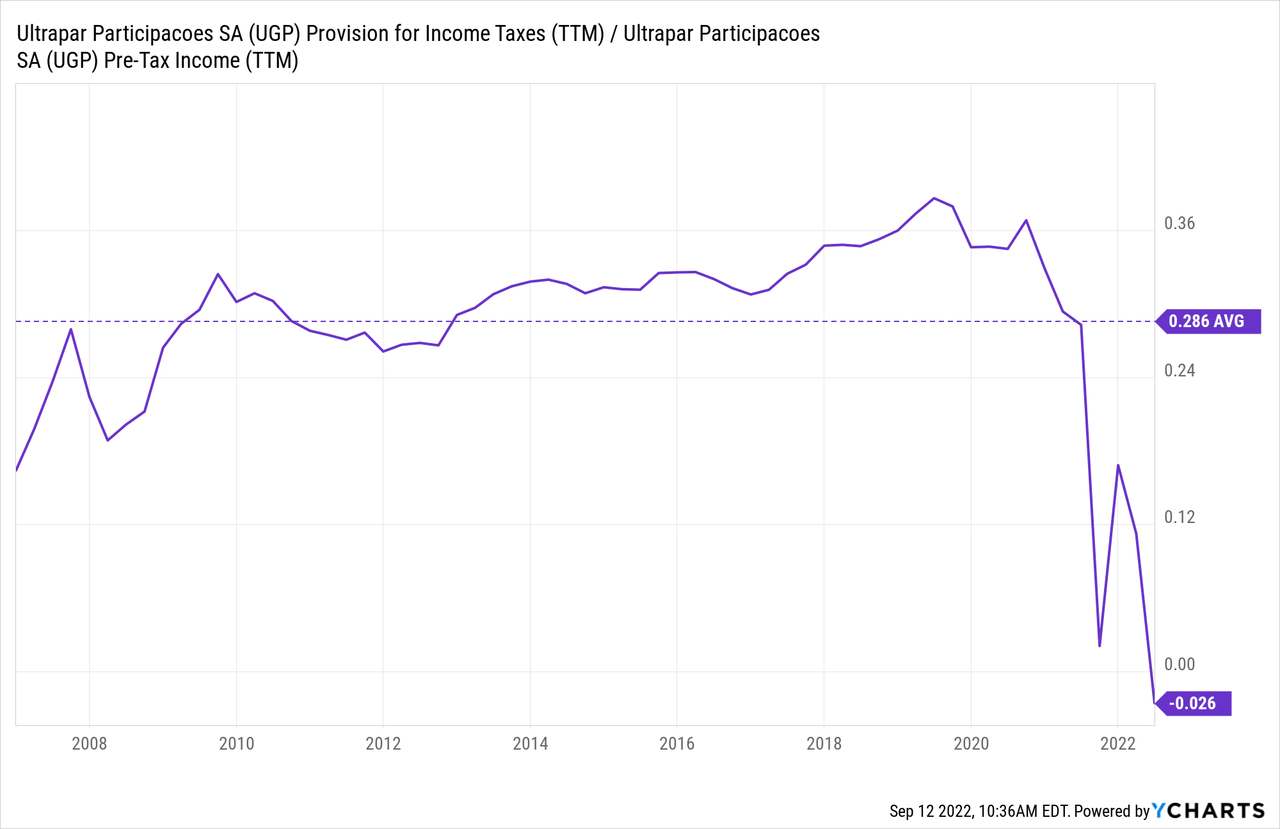

Considering an average corporate income tax rate of 30% in Brazil, UGP should generate R$2 billion in pretax income.

Dealing with debt and interest expenses is more difficult, because as we mentioned most of UGP’s debts pay variable interest rates. Assuming a long term interest rate of 10% is low compared to historical averages. However, we will use this, only to show that even with relatively positive assumptions UGP cannot earn a sufficient yield on its market cap.

With R$12 billion in debts yielding 10%, UGP has to come up with R$1.2 billion to pay interests. Added to the previous R$2 billion in pretax profits, operating income should be R$3.2 billion.

If we annualize UGP’s performance up to 1H22, we will find R$2.8 billion in operating income, which is not very far away from R$3.2 billion.

That is, assuming that the Brazilian economy continues growing, that fuel prices continue at high levels, and that UGP’s long term interest rate on its debt is lowered to 10%, then UGP is almost (but not completely) able to earn a 10% net yield on its market cap.

Conclusions

The problem with these calculations, or conversely with UGP’s share price, is that they leave no room for error. If the Brazilian economy contracts again, or if interest rates remain at current or historic levels, close to 15%, then UGP will likely not be able to earn even a 10% yield on its market cap, in my opinion.

Not only that, but a required 10% yield does not accommodate for the cyclical nature of the business, for the company’s debt risk or for the fact that it is positioned in businesses that are menaced by energy transition in the future.

In my opinion, UGP has been increasing in price moved by the Brazilian market, and not based on positive fundamentals. It provides no margin of safety to the long term investor. To some readers, UGP may be attractive as a speculative play on Brazil growing for years to come. As a long term investor, I would not recommend UGP. As a speculator, I think other companies may be better positioned to benefit from Brazil’s growth.

Be the first to comment