carlosgaw/iStock via Getty Images

Tupperware (NYSE:TUP) is at its heart an interesting business. That’s what led me to invest in the company years ago when things were still “good”. However, there are specific reasons why I believe that Tupperware isn’t as good as some investors think, and more importantly – why I think that the company might not realize its reversion potential, which seems to be the reason why many people invest in it today.

In this article, we’ll go through all of this.

Tupperware – What the company does and how it works

Tupperware’s business is simple when you look at the substance of it. The business idea is the research, manufacturing, and sale of plastic storage containers, utensils, and kitchen gadgets. The company was founded by Earl Tupper, and the company’s products were introduced to the market in 1946.

The company’s initial appeal and product exclusivity was the patented ‘burping seal’ for its containers, something which most products have some variety of today. I think it is important to point out that Tupperware no longer has any massively distinguishing characteristics to competitor products. It’s no longer unique or at a significantly higher quality, in a way that would distinguish it fairly from peers. Some may disagree – and that’s fine – let me know why. It’s not that the company doesn’t try to set itself apart – it does – but I personally don’t see a massive product advantage any longer.

The company’s structure is that the Tupperware subsidiary develops, manufactures, and distributes its products for the parent company, the Tupperware Brands Corp.

This company no longer has a dividend yield after the cut. It’s B+ rated, making it a junk-rated company in terms of credit rating, and currently has a market capitalization of less than $1B. Plenty of people, including myself, thought the company was headed for full bankruptcy, but this proved not to be the case. The company has risen back up from the ashes, and as of 2022, still provides positive EPS and decent overall numbers. The company, as of the most recent results, has no plans to reintroduce the dividend in order to maintain maximum financial flexibility.

As a company that uses plastics, the primary feedstock is resin, and the overall recent supply chain disruptions have hit company EPS heavily, with a $0.43/share 4Q21 feedstock impact.

Tupperware is a multi-level marketing (MLM) company. This means that revenues are generated from a non-salaried (typically) workforce that primarily works for sales commissions, with earnings generated from a binary compensation commission system. MLM salespeople are, therefore, expected to sell products directly to end-user retail consumers by means of relationship referrals and word-of-mouth marketing, but more importantly, they are incentivized to recruit others to join the company’s distribution chain as fellow salespeople so that these can become downline distributors.

This in itself isn’t a dealbreaker. There are companies in many fields, primarily in makeup/cosmetics, that do this and do so successfully. Typically, this is a sales model that has appealed to a female clientele, and there’s a historical reason for this.

Tupperware’s development of a direct marketing strategy (The ‘Tupperware Party’) came during the 1950s, and it enabled women to generate an income while keeping a focus on what then was “their” domestic domain. This entire plan assumed the traditional characteristic of the housewife, i.e. party planning, sociable relations with friends and neighbors, etc.).

This model really came into its own in the 1950s thanks to pioneering US saleswoman Brownie Wise. This was culturally significant because women were coming back from the war, working full-time, and were then told to essentially return to the kitchen. Tupperware was a method of empowering women to continue working and giving them a foothold in the post-war 1950s business world.

The concept spread to England, Germany, and other nations, with the company recruiting sales staff and giving incentives. Its products are now sold in around 100 countries, and Tupperware is headquartered in Orlando, Florida.

To this day, products are still mostly sold through the party plan, with rewards for the hostesses. These rewards are usually free Tupperware products based on the level of sales. In most countries, Tupperware’s sales force is organized in a tiered structure with consultants at the bottom, managers and star managers over them, and next various levels of directors, with Legacy Executive Directors at the top level. In recent years, Tupperware has eliminated distributorships in the US.

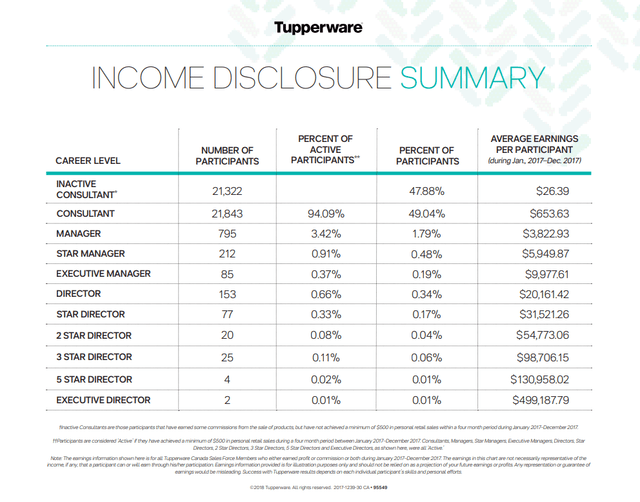

This strategy, as you might expect, has been the subject of relentless criticism. Studies have shown that salespeople for the most part (94%) remain at the very lowest level of the pyramid, making on average $653 gross during an entire year. Even so-called ‘Managers’ or ‘Star Managers’ make less than what would be considered minimum wage in the USA.

Tupperware Income Disclosure (TUP IR)

This is how the model that Tupperware operates works. Unfortunately, this model and the company itself have experienced an increased amount of operational weakness in terms of results. The company’s high leverage weakened cash flow and forced the company to cut its very high, 5%+ dividend. It was a quick dividend reduction from around $2.72 to less than $0.28, only to cut it completely in late 2019.

Tupperware’s sales declined 8.2% in 2018, another 13.1% in 2019, and 1Q20 saw sales declines of 22.9%. The company then went into crisis mode and called in an MLM CEO with extensive market and business experience. Miguel Fernandez went on to cut the organization, making it more efficient. COVID-19 came as a boon to Tupperware due to the massively increased demand for home meals and stay-at-home culture.

As a result of this, 2020 results actually turned around. Investors might be excused in thinking that the company’s EPS improvement shows a qualitative turnaround – but this isn’t the case.

The EPS improvements back then primarily came from cost savings and debt retirement, not increased sales EPS. COVID-19 might have been positive for the company’s appeal, but it still gave a negative impact, not to mention the massively increased distribution costs the company faced due to COVID-19.

In short, much of the company’s 2020 improvements were not due to quality EPS increase, but cost savings and downpayment of debt. The company crashed and burned back in early November 2021 when the company reported net sales declines in the double-digits, with sales drops in every region except South America.

The company has since then somewhat recovered, but the share price decline in early January on a 1-year basis was 60%. Even the 25% gain since then can’t really make up for that loss.

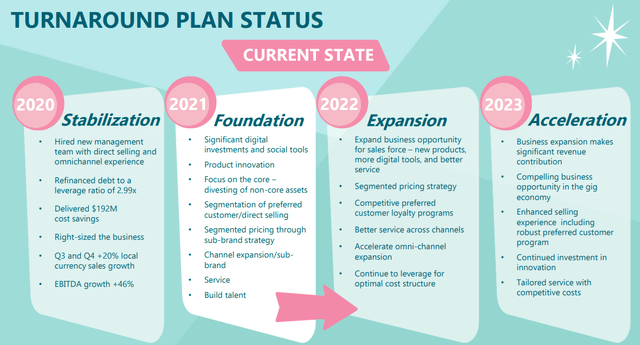

The company has implemented new measures for growth, among them a shift from traditional distribution to DTC online distribution. The company is in the foundational part of its turnaround strategy.

Tupperware 4Q21 (TUP IR)

For 2021, the company managed a net sales growth of 1%, a debt ratio of 2.1X in leverage, and a gross profit margin of around 67% with an EBITDA margin of 18%. Revenue growth on a regional level was healthy, with South America up 20% and only Asia in a full-year negative trajectory of 11%. COVID-19 remains an impact, as do distribution and input costs. 4Q21 as a whole was actually down 10% YoY.

One of the highlights for TUP has been the significant improvement in its credits, with a shift to a Libor-based (+200 bps) facility instead of a horrible, 8.25% facility. The new rate is better, with longer maturity and better flexibility. Improvements here are significant.

2022 will be the year where the company tries to move to globalized digital DTC, stabilize its Chinese operations, and accelerate new product innovation.

The current forecast for 2022 calls for an EPS of around $2.6-$3.2 for the full year, with continued feedstock and pandemic uncertainty, where the company believes the 2H22 to be better than 1H22.

Risks/Problems with Tupperware

The problem with Tupperware is sales-related, which is a bad problem to have for an MLM-type business.

This was the problem that I saw which caused me to sell my shares years ago, and it continues to be the problem I see to this day. Tupperware’s impressive margins have relied on an MLM/Party-type sales model that justifies a sales price premium. When moving to more omnichannel-based distribution, this will no longer hold water. Or at least, the degree to which it actually holds water can be put into question.

While we’ve seen operational improvements on the credit/structure side, sales have yet to show any sort of meaningful improvement – and this is a tough nut to crack. Evidence shows that when the company moves to sell through traditional retail, including Target (TGT), the results are very disappointing, with declining sales in a market where TUP products don’t warrant their premium and consumers go for the cheaper option.

After all – they’re just storage containers.

The company’s current situation can be described thusly.

In geographies where the MLM/party focus, such as Indonesia, Germany, Australia, New Zealand, and others, the company’s profitability and the market share continue to decline on a YoY basis. This is especially true with the recent logistical and input cost headwinds.

In geographies where the focus has shifted to DTC or sales through omnichannel retail, the company’s products suffer competition problems and sales declines. Tupperware, despite operational improvements, does not guide for any significant sales increase on a YoY basis. Prior to the trough in 2019, sales delivered EPS of over $4/share in the old organization/structure.

It’s, in my view, completely unclear as to how the business intends to even return to close to this level in the long term. TUP is putting its money into DTC, which is what most companies seem to be doing this day. But TUP sells a commodity – plastic containers with a well-known brand.

The entire appeal, as I saw it, was the success and sales performance of its parties. By shifting focus, the company’s products become, aside from some quality differences and the TUP brand, indistinguishable from a $2 plastic tub from Amazon.

The decline of the Tupperware legacy sales mode has been “a thing” for many years. This isn’t caused by COVID-19, logistical issues or anything like that. The top-line profitability problem has been an issue for decades. In 2013, the company’s largest marketplaces were Indonesia, Germany, and similar geographies with hundreds of thousands of sales reps. The USA wasn’t on the list any longer.

This goes hand-in-hand with some of the gender-related dynamics I spoke of in the previous segment, and it leads me to my general view on Tupperware, and the main risk associated with the business.

That risk is that Tupperware is not a company whose products/ideas can survive in the long run. They are a business made popular by a trend that is on the out. Their products lack the distinguishing characteristics that make them a “must-have”, next to any other plastic container out there. With the removal of the MLM and the introduction of DTC, this will come more to the forefront, and I see it likely that sales will continue to see flat or declining trends. I point to recent sales numbers to justify this. At best, for the long term, I believe Tupperware may become a takeover/M&A target, though I’m unsure for whom.

While I may be exaggerating or overplaying how quickly this may happen, I argue that there are many companies on the market at attractive prices that do not suffer from this decline risk, and these should be favored above Tupperware.

Let’s turn to numbers.

The valuation

I’ve spoken about what’s under the hood in terms of quality. Let’s look at numbers.

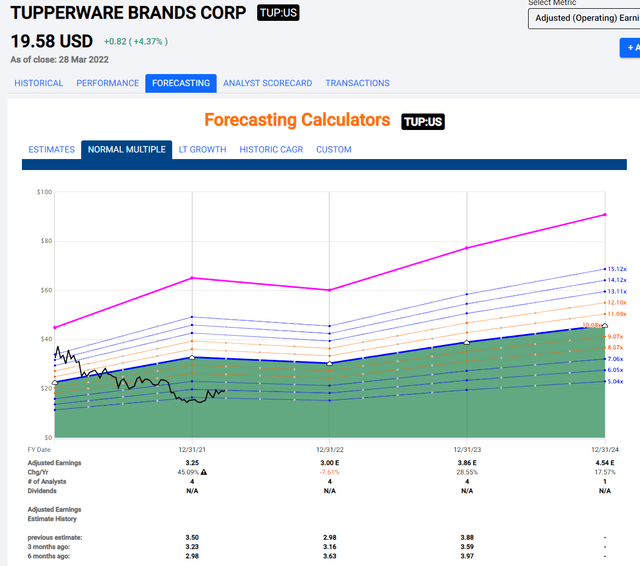

Tupperware trades at a P/E of around 6X, which makes it cheap, but I also argue that these are not “high quality” earnings, as they primarily are a product of cost savings and debt reduction, not actual sales increases. TUP does not expect to massively increase sales, and FactSet expects a 2022E EPS of $3/share. Remember that the company itself guides for a lower target range of $2.6/share, which would be a significant earnings decline. This also lines up with the analysts’ performance.

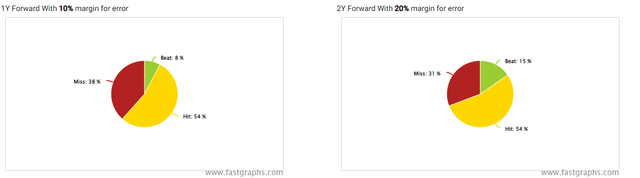

Tupperware FactSet analyst accuracy (F.A.S.T graphs)

So, none of these forecasts are in any way safe. And looking at the successive years and the targets, you can see just how these targets are shifting around and how volatile it’s expected to be.

F.A.S.T graphs Tupperware (F.A.S.T graphs)

There is no forecast safety to be had in Tupperware. Therefore, to point to this forecast/trend and say that it’s likely is, to my estimate, flawed. And because this is hard to forecast, it’s equally hard to consider where the company might go. Until earnings normalize with the new organization in place, and we see what sort of continued, recurring EPS we can get from a DTC-focused Tupperware, it seems too risky for me to even consider a high target for TUP.

Analysts give the company a range of $25-$43/share, with an average of $31.5, indicating an undervaluation of 60%.

I do not agree with this assessment. Also, these are 4 analysts that have been following TUP for a long time, and they have mostly maintained their “BUY” stance through thick and thin. The company, as such, is somewhat underfollowed. Valuing it to public comps is hard as well, because most public comps aren’t in the same situation as here and consequently rank higher in terms of EV/EBITDA, P/E, and revenue multiples. TUP is currently at a 0.9X NTM EV/Revenue multiple, which is neither far above or below the 3-year historical mean, though an argument could be made that a higher multiple should be applied here – but this would be based on the older organizational structure which no longer really applies.

The argument for the company’s undervaluation relies upon comparison to an older organizational structure that is no longer fully there, or the appeal of a legacy business model which, to my mind, is in clear decline.

I, therefore, don’t agree with the undervaluation argument here and consider Tupperware to be a “risky” investment here.

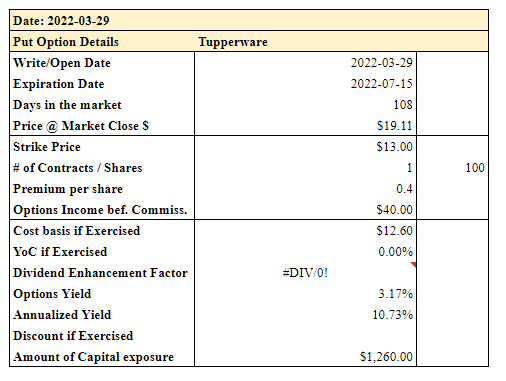

The one saving grace I see for investing in TUP would be to look at some of the available options. The July 15th $13 strike PUT options trade at a bid premium of $0.4/share as of writing this article. This would imply an overall annualized level of return of 10.7%.

Tupperware Options (Author’s Calculations)

However, in my mind, there are easier ways of making 10.7% annualized and with a good yield on top of it. While this is a possible and even cheap contract you could write, I still would avoid Tupperware here.

Thesis

While it can be argued that Tupperware is a potential turnaround story in the making, or even a potential M&A candidate at the right valuation, the moving parts in the company and its appeal in a DTC world aren’t clear enough to me to even consider them a viable investment at a 5-6X P/E. The company has failed to show sales stability over the past few years, and going forward the one positive I see is that the company has a handle on its debt and organization.

However, that does not make it attractive in terms of its products, as evidence shows that when put against other products in a non-MLM setting, Tupperware does not seem to do well. Pricing the products in accordance with competition would erode the company’s margins further, with a subsequent valuation decline as a likely result.

For now, I am a “HOLD” on Tupperware. If you believe in the turnaround, I’d be curious to hear your thoughts. If you own the company at a profit because you were smart and bought them at dirt-cheap valuations of essentially less than $2/share, then I would argue the time has come to rotate those profits.

Remember, I’m all about :

1. Buying undervalued – even if that undervaluation is slight, and not mind-numbingly massive – companies at a discount, allowing them to normalize over time and harvesting capital gains and dividends in the meantime.

2. If the company goes well beyond normalization and goes into overvaluation, I harvest gains and rotate my position into other undervalued stocks, repeating #1.

3. If the company doesn’t go into overvaluation, but hovers within a fair value, or goes back down to undervaluation, I buy more as time allows.

4. I reinvest proceeds from dividends, savings from work, or other cash inflows as specified in #1.

If you’re interested in significantly higher returns, then I’m probably not for you. If you’re interested in 10% yields, I’m not for you either.

If you however want to grow your money conservatively, safely, and harvest well-covered dividends while doing so, and your timeframe is 5-30 years, then I might be for you.

Thank you for reading.

Be the first to comment