Jonathan Kitchen/DigitalVision via Getty Images

The generally accepted view amidst the 2022 market crash is a consequence of the Fed’s generous QE as a response to the pandemic in the last 2 years. An unexpected sharp change to quantitative tightening (QT) is sending the markets down, as a result of the reduction of money in the markets, rising rates and recession worries. However, it is important to understand the mechanics of the QT and its impact on markets in detail. Short analysis reveals that the broad money supply remains irreversibly large, with large cash balances both at the household and fund level. Any sign of improvement could fuel a large rise in valuations.

The Easy Money Narrative

OK, the basic narrative of the abysmal, appalling market of 2022 is something like:

‘This time round, the money printing has gone too far. The Fed, ECB and other central banks printed trillions, then bought the markets and subsidized people.

This put a floor under the markets when it was most needed as the pandemic unfolded in 2020, but then they kept buying even as the economy strengthened, flushing the markets with cash ad infinitum.

Money eventually seeped into all corners of the economy, from mounting house prices to meme trading and just plain gambling with money on anything that had a meme potential or was hard to understand.

And! Inflation.

The central bankers had to admit defeat, stop calling the inflation transitory and begin tightening. The markets are bleeding because, you know, the free money is gone.’

Is it?

The Money Problem

Recently, Lyn Alden made an interesting observation on Twitter:

One thing to keep in mind: When the broad money supply is increased, even when it is initially spent or invested, someone else receives it and spends it or invests it again. That new money mostly remains in the system forever.

This is an important point that goes to the heart of how the monetary system operates.

In 2020, the Fed didn’t just buy the markets, they went further. As explained by Lyn Alden here, in a normal quantitative easing (like we have seen after 2008, for example), the Fed would buy treasuries and some other securities (mortgage-backed securities) from banks.

This is because the banks at the time were very levered, meaning they could not lend to the economy to keep the economic wheels turning. The Fed would create money out of thin air, then buy things from banks, and as a result, the banks had suddenly very healthy reserves and could resume activity.

It does not mean they would. They wouldn’t forcibly lend to people. In fact, the QE post-2008 was mostly deflationary. The money stayed in the banking system, but the asset purchases also made the rich richer, and making a huge mental shortcut here, eventually found its way to venture capital funds, astronomic startup valuations and the stock market.

In 2020, however, the banks had healthy reserves, buying things off of them would not do much. And so the Fed with the help from the Congress and Treasury engaged in the most direct form of ‘helicopter money,’ essentially writing people and small businesses checks. This is factually more inflationary. The money went into the hands of people.

There is a somewhat dull debate to be had as to what is causing the inflation and how little of it is in the hands of central banks, as the impact of the Russian expansion, rising commodity prices and broken global supply chains are pushing the prices up.

These inefficiencies are baked into the economy of every country, no matter what central banks do, but I will not spend more of the text on this here because I am not statistically gifted, but also because this topic is heavily covered by every FT and the like.

And regardless, the truth of the matter is that the central banks are left with no choice but to keep doing what they are doing – for the first time in a long time, reversing course and tightening – which seems to be hurting markets immensely.

Quantitative Tightening

So, the inflation proved to be very non-transitory. The central bankers have to raise rates and let the securities that they bought from banks (and markets) mature. This means that they don’t roll them forward, i.e., they want to be repaid the principal.

This has already begun. In June, the Fed let $15 billion of treasuries mature, not reinvesting the proceeds back into the market. In the months ahead, this will continue at the pace of $30 billion (later increased to $60 billion) for treasuries and $15 billion for mortgage-backed securities.

This should reduce the debt and amount of money in the system. And it does, but it is not a 1-to-1. The monetary expansion of 2020 cannot be sucked out of the economy just like that.

This time around, the money did not stay in the banking system; it was given to people who spent it or invested it, and as Lyn writes, someone else, therefore, received it and spent it or invested it again. That money stays forever.

We live in a narrative economy. The Fed has a unique power to destroy paper wealth and thus suppress consumption and investing. By raising rates and reducing its balance sheet, the Fed effectively made debt more attractive vs. high-growth tech stocks.

The interest rates on debt increased, while the earnings of growth stocks are further in future, now discounted at a higher rate. This does, of course, ignore several layers of complexity, and the fact that worries about recession are also weighing down on the markets, but it captures well the basic mechanism in force.

Negative Wealth Effect Is Real

Rising mortgage rates leave people with less money, and may eventually (if persistent) translate into falling house prices. Falling house prices, like, falling markets make people feel less wealthy, so they spend and invest less. This, in effect, should slow down inflation.

This destruction of paper wealth is not equal to cash impact. Markets rise and fall incrementally. When valuations go up (or down), this does not mean their increase (or decrease) is equal to cash changing hands.

When a price of a stock goes from $100 to $300, it does so in increments – i.e., not every $1 of increase in price results in a $1 exchange between buyers and sellers. The same is true in reverse.

The year 2022 has so far deleted $0.5 trillion of U.S. household net worth, according to Fed. This is, if you think about it, stocks and other instruments changing hands at falling prices.

When an investor sells a large number of shares priced at $200 for $195, she gets $195 in cash (or entry at her broker’s account) and $5 of wealth is deleted.

Meanwhile, this new supply, if large enough, might decrease price for other sellers even further to, say, $180. They get $180 and the $20 evaporates. Not every $1 of falling price is $1 in someone’s hands.

Or to put it in perspective, $1 billion of selling can wipe out $30 billion of market value on the way down.

Cash Is Real

Still, some of it is real money going to someone’s pocket. A lot of money, actually.

Money owned by U.S. households held at bank rose to $15.75 trillion at the end of Q1. This shows the impact of the market fall when it was still relatively moderate, before it began really crashing in Q2.

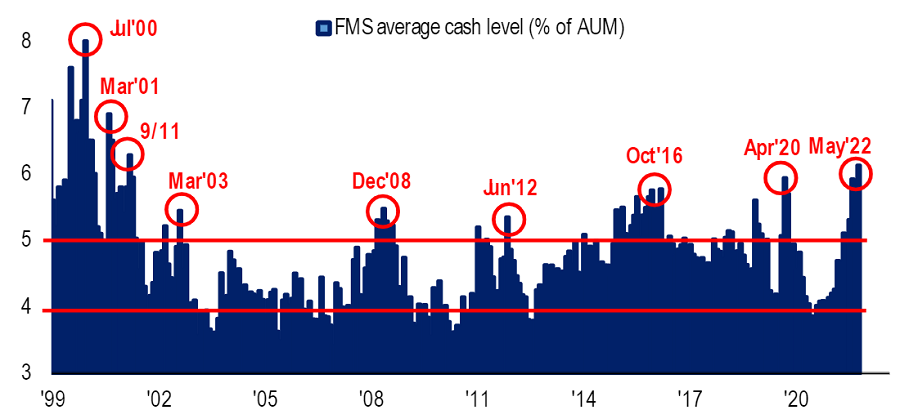

A report by Bank of America shows that fund managers are hoarding cash at record levels not seen since 9/11.

Funds Hoarding Cash (Bank of America Global Fund Manager Survey – May 2022)

Summary

You know what the conclusion is. Things are bad, but that does not mean that the everything bubble has burst. In a narrative economy, even a slight change of tone can turn the investor sentiment and the money starts pouring in.

That is not to say that the Western world does not have structural problems. The global macro might have changed for good, prioritizing ‘real’ things (commodities, energy, defensive stocks) over growth. But, sooner or later, the money will pour back into the markets. The question is where.

Be the first to comment