India’s deficit with China has increased to more than $40 billion recently – and this of course is not a viable situation. MicroStockHub/iStock via Getty Images

The ‘made in China’ roadmap

India is not going to become China anytime soon. It will take at least 10-15 years and the nation will need to (i) attract foreign investment flows, (ii) bolster its infrastructure (the groundwork for business to flourish) and (iii) focus once again on exporting industrial products.

Pretty much what China has been doing, from the year 2000 and up until early 2018, when its economy started to mature, prompting the Asian nation to emphasize on domestic consumption and services instead – trailing the economic model of developed nations.

India is about to walk into a trap, as its economy is being wrongfully pushed into premature maturity by its economists and corporate elite. If it persists in moving down this path, the Indian economy will stop expanding fast and will only be able to maintain mild growth rates.

It should instead track China’s past steps (a proven strategy), while continuing to expand its lucrative tech sector and keep food inflation in check. The later has been successfully managed by minimizing futures trading for food commodities, maintaining socio-political stability as a result.

Deficit-based growth cannot last forever

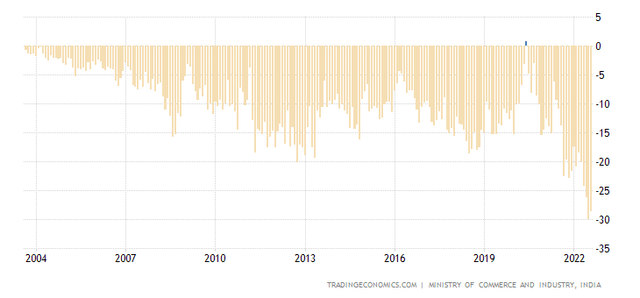

One of India’s greatest problems is its ever widening trade deficit. The graph below reveals just how bad things have become, exactly because its economic advisors decided to invest into the wrong economic model.

India, Trade Account Deficit – “The 2022 deficit has expanded due to inflation, especially in regards to energy related products and electronics” (Source: Tradingeconomics.com)

Developed nations can import large amounts of industrial grade goods, because they have the capacity to export higher value products that even out (in part) their trade accounts. India is not such a country (yet) and as a result deficits are spiraling deeper by the year.

The 2022 deficits have further widened due to the nation’s dependency on energy imports, as well as electronics and fertilizers that it brings in primarily from China. The Asian tiger will continue to be “hungry” for more such commodities over the next decade, without there being any evidence of a long term plan on how to even out trade flows. In fact, the deficit with China has increased to more than $40 billion recently – and this of course is not a viable situation.

For India to narrow down its deficits, it has the following options:

- To deal with energy imports, the only alternatives are expanding existing storage capacity for oil and gas, further diversify sourcing and invest more into solar parks. Until new technology becomes utilizable (hydrogen power stations, fusion reactors), there are no other options really. Smaller modern nuclear reactors could also help reduce the burden, as long as India strictly maintains security protocols. Plants the size of Kudankulam are risky projects (e.g. terrorist attack, multiplied explosions like Fukushima).

- To reduce dependence on Chinese industrial products (electronics among other things), India must boost its own capacity to produce. In doing so, it will not only close the enormous trade gap with China, but it might even compete with the nation. As the greater West tries to wean itself off Chinese imports, India has the opportunity to take over those markets. Trade data already prove that Europe is increasing its imports from India, often times ‘offering’ trade surpluses to the later.

For the above to materialize, India must opt for foreign investments. The country should initially redirect these (potential) funds to regions that already have the necessary infrastructure and strive to quickly create an exporting capacity that will allow it to close small-sized deals.

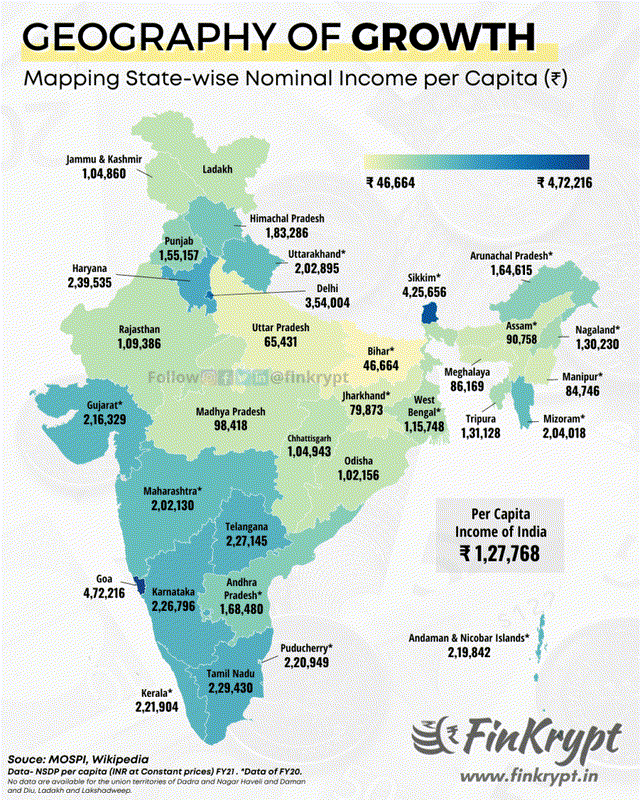

India, regional per Capita income – “There are major income and infrastructure imbalances that need to be addressed, to maintain socio-economic stability within the nation” (Source: Finkrypt.in)

Similar to the case of a client (importer) seeking out a trustworthy supplier (exporter), initial orders are small in size and value. Once the client is persuaded that the supplier can be trusted (quality and quantity wise), larger orders start coming in. At that point, India should invest heavily into less advanced regions and couple that with necessary infrastructure investments. This would then ultimately set the stage for a long term development plan and a more socio-politically stable India.

Truth being said, India has little to gain from engaging with the newly forming ‘East Alliance’ (China, Russia, Iran and others). China needs its export markets and won’t allow the nation to compete for Asia (a rather vast market) and while Russia has the energy it so desperately needs, the war in Ukraine will force the Asian tiger to eventually pick a side (if it becomes a lasting one). If it moves away from the greater West, it will lose funding and a market thirsty for industrial products (exports) it can offer – and which in the past helped China become the economic powerhouse it is today.

Is Wisdom’s EPI ETF a good long-term choice?

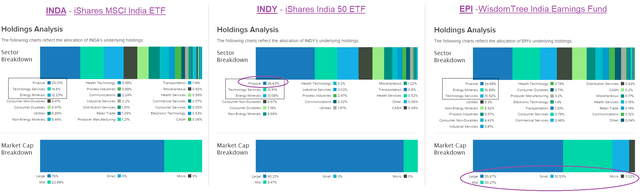

The safest way to utilize the above information is to pick an ETF with a broad sector allocation. After all, if India was to solve its trade deficit problem and spur investments, “the tide would raise all boats”. Below I have combined the top 3 ETFs, by assets under management (not sequenced accordingly).

*Sector breakdown rates have recently changed. I use older/average ones for them to be more representative of the past 10 years we are going to discuss (Source: ETF websites, compilation averages)

- Most investors prefer INDA – iShares MSCI India ETF, because it is well diversified (116 stocks), its sector breakdown is in accordance to India’s economic model and it focuses primarily on large caps.

- INDY – iShares S&P India Nifty Fifty Index ETF on the other hand seems to heavily rely on the finance sector and focuses only on 60 companies (quiet the risk in both cases).

- EPI – WisdomTree India Earnings ETF is enormously diversified (440 stocks), but it has allocated 45% of the funds into medium, small and micro caps. Which puts returns at risk if suddenly a liquidity crisis was to unravel, in which case smaller companies are usually the first to get hit.

The above notes justify why INDA is the leader by AUM. But a bit of a closer look (see graph below) might tell a different story:

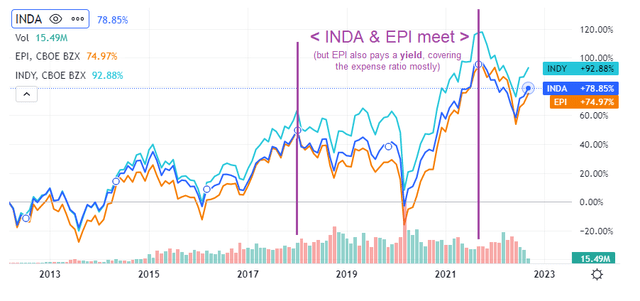

India ETF comparison (INDA, INDY, EPI) (Source: Seekingalpha.com)

INDY posts the highest returns over the past 10 years, which makes sense being that it is also the riskiest ETF of the three (finance, 60 stocks). EPI posts the lowest returns, but over the years it has periodically “met” with INDA’s returns (see purple vertical lines). Plus, the difference between INDA and EPI is actually just 4%. But EPI pays a yield of about 3% (or more), which well covers its expense ratio. And it does make a difference when we talk about a 10 year span.

So all and all, the reality for the past 10 years is that INDY and EPI are actually both a better choice than the most famous INDA. Net returns are for both higher and when INDA and EPI meet, if one was to sell, EPI would have been a much better choice than INDA.

INDA seems to be an “intuitive” choice rather than an objective one. Overall EPI seems to be the better choice, especially after a major market pullback, which bolsters the yield. But until policy changes signal a focus on domestic industrial production of electronics, coupled with EU trade deals that will attract funding, one shouldn’t expect ETF returns to resume growth.

Be the first to comment