fazon1/iStock Editorial via Getty Images

A spin off and operational independence for HSBC’s (NYSE:HSBC) Asia business could unlock $26.5 billion in shareholder value, more than a fifth of its current market value – or so we have been told by a report commissioned by its largest shareholder, Chinese insurance company Ping An Insurance Group (OTCPK:PIAIF) (OTCPK:PNGAY).

Two alternative scenarios that Hong Kong consultancy firm In Toto suggested could benefit shareholders are for HSBC to spin off its Asia business or just its Hong Kong retail operations via partial initial public offerings. Unlike the first proposal, HSBC could retain a majority stake and operational control of the spun out unit.

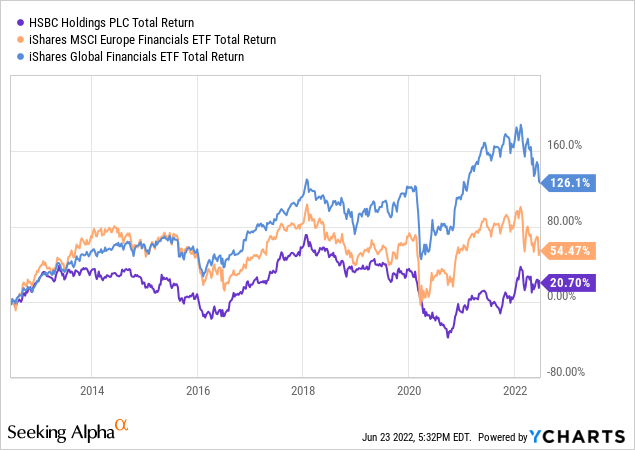

There are definitely reasons to dislike the status quo. Shareholder returns have hardly been something worth boasting about – total returns over the past decade have lagged some way behind sector peers.

What’s more, geopolitical tensions have meant that HSBC has had to walk an increasingly slippery tightrope between Chinese and Western interests. And with these political and regulatory frictions not going away in the foreseeable future, HSBC’s balancing act looks increasingly untenable.

It has also been suggested that splitting the group into two could unlock valuations and growth in its Asia business. Asia accounts for 65% of the group’s reported profit before tax, yet only a minority of risk-weighted assets belong in the region – implying an inequitable allocation of resources.

These are good arguments against how HSBC is currently structured, but would a break up really create shareholder value? The banking industry is unique, where successful spin off stories are few and far between. Breaking up the bank could cause it to lose significant revenue, cost, funding and liquidity synergies.

Analysts from Barclays are unenthusiastic about the proposal – they estimate doing this could reduce HSBC’s value by between 3-8% and cost it billions of dollars in separation costs.

Regional Business IPOs

Regional business spin offs via partial IPOs are certainly not unheard of, and similar moves have been made across a range of industries. Recent examples include Anheuser-Busch InBev’s decision to separate its Asian business in 2019 and Nissin Foods’ partial IPO of its China and Hong Kong operations in 2017. In the financial sector, American International Group (AIG) spun off AIA, its Asian life insurance arm in 2010, while British insurer Prudential demerged its US arm, Jackson Financial, as recently as September 2021.

That said, it’s important to understand that the desire to raise capital is usually the primary motivation behind such action. AIG sold its most promising asset in order to pay back part of the $182.3 billion bailout it received from the government during the financial crisis, while the other aforementioned groups sought to reduce debt and improve financial flexibility. By contrast, HSBC, which has a CET1 ratio of 14.1% and is scaling back from less profitable markets, is not in need of fresh capital.

Moreover, the track record for such break ups have been mixed. AIA has flourished under its independence – the value of its stock has more than quadrupled since its IPO – though AIG has missed out on much of the gains, as the former owner quickly sold down its stake to repay the US government. Meanwhile, Prudential has seen little benefit – its stock has lost more than a third of its value since separation.

Synergies

Banking and insurance have very different business models though. Diversification and market opportunity are the predominant motivators for insurers to spread across multiple markets, while funding, liquidity, cost and revenue synergies play a more significant role for banks.

Cross-border business is vital for investment banking, and so the rationale for maintaining a presence across regions is stronger for a bank such as HSBC. A substantial presence in developed western markets is needed to help you win customers – in other words, there are network effects from being a global bank. And HSBC is more exposed than many of its rivals, given its outsized market presence in cross-border financial transactions, especially in dollar payments.

HSBC has argued that while Asia appears to be its most important market, much of this is actually business with Western clients that gets booked in the region. The Asian business, post demerger, would therefore need to maintain a meaningful presence in New York and London, as well as other financial centers outside of Asia. A clear separation based solely on geography is therefore not practical, and so nor can geopolitical risks be eliminated.

Capital savings are uncertain too. With assets of more than $1 billion both inside and outside of Asia, the two separate businesses will almost certainly remain classified as Global Systemically Important Banks (G-SIBs) and therefore continue to face additional capital buffers. The capital surcharge to its ratio of Common Equity Tier 1 capital to risk-weighted assets, currently at 2.0%, may only fall slightly, if even at all. Meanwhile, the two less diversified units could face greater earnings volatility, and therefore demand higher costs of capital too.

On the cost side, the two separate banks will likely spend more each year to sustain the extra staff needed in areas like technology, administration and compliance. And then, there are the separation costs to consider. The cost of ring fencing its UK retail bank was estimated to cost the group around $2.4 billion. A spin-off of its entire Asia business would likely be even more costly, given its greater size, spread across multiple countries, complexity and extra work needed to achieve complete operational independence.

Banking is a highly competitive market, so the passing on of higher costs to clients would not be well received. It could quite simply lead to revenue and market share losses. It’s also important to remember that the only motivation HSBC had for separating the UK retail unit was because it became a legal requirement to do so, and certainly not as a way to boost returns.

Investor Discontent

Nevertheless, the proposals could gain traction with Hong Kong’s mom-and-pop shareholders. Many retail investors there are still sore about how HSBC’s regulator, the Bank of England’s Prudential Regulation Authority, forced the group to suspend dividend payments at the height of the pandemic. Collectively, retail investors in Hong Kong own around a third of HSBC’s shares, and so they could potentially decide the fate of the group.

It’s hard to put the finger on just how much support there is for a break up of HSBC. As history shows us time and again, the loudest voices seldom represent the majority view.

Retail investors are a disparate group, and poor voter turnout means their influence is often limited. When some shareholders in Hong Kong sought to call an extraordinary general meeting (EGM) to express their dissatisfaction with the dividend suspension in 2020, they failed to secure at least 5% of the total voting rights needed to force it to happen.

More could be swayed this time, and so do expect a charm offensive to this group of shareholders from both sides. The two matters are separate, although they are connected. There was no realistic chance in successfully overturning the decision to scrap the dividend while the group remained domiciled, and therefore regulated, in the UK – and so there was little incentive to participate then.

On the other hand, this idea of breaking up the bank is legally actionable. And so should Ping An successfully tap into lingering investor discontent, more retail investors could be motivated to support a proposal that they believe could better protect their interests.

Still, more support will be needed from big institutional investors. Yet, as of now, none of HSBC’s other major shareholders have come out publicly in support of the proposal to split the banking giant into two.

Hong Kong Retail Separation

A separation and partial IPO of its Hong Kong retail banking business could be a simpler affair. After all, the bank has had to do something similar with its UK retail unit in 2018, following the introduction of ‘ring-fencing’ rules there in the aftermath of the global financial crisis of 2007-8.

HSBC already has something similar with its 62% stake in Hang Seng Bank, a majority-owned subsidiary which operates alongside (and to some extent, also competes against) its much larger self. A listing of its HK retail unit could even be effectuated via a reverse merger, with Hang Seng Bank buying HSBC’s retail operations in the territory.

Retail banking, with the exception of private banking, relies much more on local scale rather than global scale, and so the unit could easily survive on its own. HSBC’s corporate structure as a collection of locally-incorporated subsidiaries also restricts the use of excess deposits in the region from being deployed elsewhere, meaning funding synergies are limited. Moreover, regulations since the financial crisis have already made it more difficult to move liquidity around.

That said, there is a funding advantage from keeping the retail bank and its investment bank together, which would be lost from a clear separation of the two. HSBC’s competitive advantage with corporate customers is partly underpinned by its ability to lend at substantial scale, something that currently relies on its cheap deposit-funding from retail customers.

Its Global Banking and Markets division in Hong Kong had a loan-to-deposit ratio of 141% in 2021, compared to just 48% for the rest of its operations in the territory. With one side of the bank clearly in a deposit-deficient position and the other with a surplus of deposits, the two units are a complementary fit.

In the current structure, the investment bank does not need to rely on volatile wholesale funding, and so liquidity risk is lower in its current structure. And that is before we consider any risk of corporate deposit outflows. This could mean that post-separation, the investment bank may need to raise additional capital to maintain its current credit ratings.

Furthermore, it’s also important not to forget the benefits go both ways – the investment bank in turn helps the retail bank by putting its excess deposits to good use, enabling both sides to earn a better return.

Final Thoughts

A break up of HSBC is unlikely to ease the group’s political frictions, nor unlock significant, if any, shareholder value, in my opinion. While some regional spin offs in other sectors have been successful, the banking business model is very much different. And to make things more tricky, splitting up a bank will be messy work, making any attempt to do so an even more costly and risky endeavor.

This all seems like an unwelcome distraction then.

Be the first to comment